The latest phase of Afghanistan’s decade-old conflict effectively ended soon after 15 August 2021 when the Taleban captured Kabul. In a matter of weeks, the movement would control the whole country as it defeated the last remnants of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) that had fought on and as the final American and other foreign troops left. The end to the conflict between the three major armed actors of the post-2001 period – the Taleban, foreign military and the Islamic Republic’s security forces – brought with it a dramatic fall in the number of civilians killed and injured, although not to zero.[1]

Between 15 August 2021 and 30 May 2023, when UNAMA’s data set for this report ends, it recorded 3,774 civilian casualties, 1,095 people killed and 2,679 wounded.[2] The figures for that 21 month period were substantially lower, in terms of the average monthly civilian casualty toll, than for any single year since 2009 when UNAMA began systematically recording civilian casualties. In 2009, the average number of civilian casualties per month was almost three times greater than in those 21 months; in 2016, it was more than five times higher.[3]

The reduction in civilian casualties since 15 March 2021 is even more striking compared to the especially brutal months leading up to the fall of Kabul. The final quarter of 2020 was the worst ever recorded for civilian casualties; they rose as autumn became winter for the first time ever (see AAN reporting here). Then, in the first six months of 2021, UNAMA recorded almost 5,200 deaths and injuries, with nearly half taking place in just two months, May and June 2021.[4] In the face of these terrible casualty figures, AAN wrote that “any notion that the Taleban capture of territory since 1 May has been virtually bloodless has been demolished by UNAMA’s mid-year report on civilian casualties… The surge in civilian harm coincided with the Taleban’s push to take territory.”

Over the twelve and a half years between 2009 and 30 June 2021, when UNAMA published their final pre-takeover report, they recorded 55,041 civilians as having been killed or injured in the conflict. These are the casualties that UNAMA was able to verify – the actual figure will be even higher.[5]The respite from conflict-related violence, which came with the Taleban’s return to power, was for most people, immediate and has been lasting. Many have been able to travel for the first time in years, to farm without fear of artillery shells or air strikes and shop or go to work without fear of attack. However, not everyone has seen the risk of attack reduced. Although violence is now at much lower levels, it is far more targeted at particular communities. Moreover, most civilian casualties appear to be not collateral damage in attacks on military targets but the result of deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian objects.

UNAMA’s focus on IEDs in the report

Roughly three-quarters of the total number of civilians killed and injured in the period covered by UNAMA’s report, 15 August 2021 to 30 May 2023, were victims of IED attacks; UNAMA includes in this category both suicide attacks (IEDs fixed to the person) and IEDs fixed to vehicles or laid on roads or in buildings. That high number is why it has focused this report on IEDs and the “casualties of indiscriminate IED attacks in populated areas, including places of worship, schools and markets.” It does also make mention of two other sources of casualties since 15 August 2021 – targeted killings (148 civilians killed and injured) and people harmed by explosive remnants of war (639 civilians killed and wounded).

UNAMA attributes the majority of casualties from IEDs in the 21 month period under study to ISKP (1,701), but says “[a] significant number of casualties (1,095) … resulted from IED attacks which were never claimed and/or for which UNAMA was unable to attribute responsibility.” The increase in ISKP-authored attacks came after a period in which their use of this means of attack had reduced (see chart below).

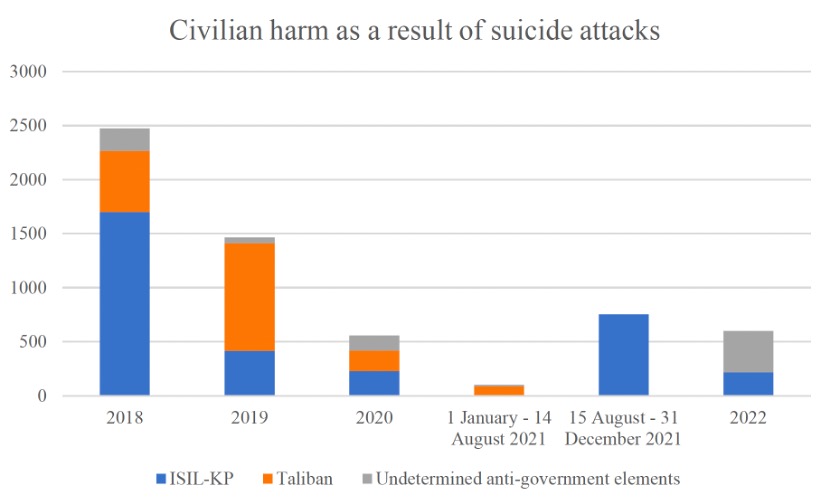

UNAMA also points to how suicide attacks have become more deadly since the takeover, with greater numbers of civilians now being killed or wounded, on average, in each attack. This is despite another trend, a drop in both the number of suicide attacks and resulting overall civilian casualties every year since 2018, from 50 attacks causing 2,473 civilian casualties in 2018 to 8 attacks causing 855 casualties in 2022 (see table below). However, from 2018 to 2020, the average number of civilians killed and injured in each suicide attack was never more than 49 (in 2018). In the period following the takeover in 2021, the number of casualties shot up to an average of 251 civilians killed or injured in each attack (all attributed to ISKP) and 75 per attack in the following year.

Who is being targeted/harmed by IEDs?

UNAMA highlights three areas of concern: attacks on places of worship, attacks targeting Hazaras, and the harm done to civilians in attacks targeting the Taleban.

More than one-third of all civilian casualties recorded by UNAMA since the Taleban takeover have come in attacks on places of worship. It had documented a fall in the number of such attacks over recent years, but since the takeover, they have shot back up again. There were nine in 2018 and in 2019 (435 and 219 civilian casualties, respectively); six in 2020 (34 civilian casualties); one in 2021 before the takeover (35 casualties); four in 2021 after the takeover (583 casualties) and; 14 in 2022 (631 casualties). UNAMA attributed the majority of casualties resulting from these attacks to ISKP – nine separate attacks resulting in 853 civilian casualties (284 killed, 569 wounded). The chart below shows the civilian casualties resulting from such attacks over the past five years.

More than half of all civilians killed and injured in attacks on places of worship were Shia Muslims (686 out of 1,218). Others targeted were Sufis (331) and Sunnis (196) – going from press reporting, it seems likely that most of the Sunnis targeted were Salafists, although UNAMA provides no detail here. Five Sikhs, among the last remaining members of what was a thriving community before the 1978 Saur Coup, were also deliberately killed and injured.

Ethnic Hazaras, the majority of whom are Shia Muslims, were killed and injured in large numbers not only in their places of worship, but also in schools and educational facilities, on public transport and in the crowded streets of neighbourhoods where they form a majority. Since the takeover, UNAMA has documented 345 Hazara civilians killed (95) or wounded (250).

UNAMA has detailed some of the attacks suffered by Hazaras in Kabul in this period, including two attacks in Muharram in August 2022, an IED explosion killing three civilians and wounding 54 others in a market on 6 August and an IED attached to a minibus that killed two people and wounded 22 others the following day. ISKP claimed both attacks.

That same year, three attacks on educational facilities in the Hazara neighbourhood of Dasht-e Barchi in Kabul also caused at least 236 more civilian casualties. On 19 April 2022, consecutive IED attacks were carried out, on the Abdul Rahim-e Shahid High School (18 killed, 44 wounded) and Mumtaz Educational Centre. Among those killed and wounded were 47 children (12 boys killed and 34 boys and one girl wounded) and four women (one killed and three wounded).

Later in 2022, on 30 September, a suicide attack against Kaaj Educational Centre, also in Dasht-e Barchi, left 168 people either dead (54) or wounded (114): most were young women and girls (48 killed and 67 wounded). The youngest victim was a 14-year-old girl injured in the attack.

If the number of civilian casualties in attacks on Shia places of worship and Hazaras are added together, the scale of the onslaught on these overlapping communities[6] is clear: out of a total of 2,814 civilians killed or injured in IED attacks in the 21 month period under study, 1,031 were Hazara and/or Shia. UNAMA attributed the majority of attacks against Hazaras to the sectarian ISKP, but a significant number, including the three attacks on schools and educational centres detailed above, remain unclaimed and unattributed. UNAMA gives no breakdown of the number of attacks on Shia places of worship it attributes to ISKP, but overall, it said a majority of attacks in the period against all places of worship were by the ISKP (9 out of 15.) Unfortunately, this is a pattern of targeting that predates the Taleban’s return to power, as can be seen in our in-depth January 2022 report by Ali Yawar Adili, which explored attacks on Hazaras/Shias and the authorities’ response, both during the Republic and the Emirate, “A Community Under Attack: How successive governments failed west Kabul and the Hazaras who live there”.

A final focus in UNAMA’s report are the civilians caught up in IED attacks that target the Taleban. It has verified 426 civilians killed (63) or wounded (363), both bystanders and civilian officials of the Islamic Emirate. More than two-thirds of these attacks, it said, were claimed by ISKP.

Conclusion

In its report, UNAMA calls on armed groups to “[c]ease the indiscriminate and disproportionate use of all IEDs, particularly in populated areas, and the targeting of civilians and civilian objects, such as places of worship and educational facilities.” It has also asked the Taleban to conduct “independent, impartial, prompt, thorough, effective, and transparent investigations into IED attacks, making the utmost efforts to identify and prosecute perpetrators of attacks” and, “[i]n consultation with affected communities, particularly Hazaras, increase efforts to strengthen security and protection measures in places of worship, educational facilities and other areas at risk of attack from IEDs.”

The Taleban, in their response to the report made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, have said Emirate security forces are actively and successfully pursuing ISKP and “the level of civilian casualties has dropped and is dismounting and with the passage of time, we will witness absolute decrease in insecurity.” The ministry also said the “security of places of worship, holy shrines, Madrassas, Shiite places of worship and learning centers … is a priority for the security forces.” Its attention to its duty to protect all Afghans, including Hazaras, was clear from the fact that “on some occasions, even the Mujahedin of the Islamic Emirate [have been] martyred defending the Shiite. For instance, on August 5, 2022, as a result of a huge explosion during Ashura ceremony in Sar-e-Kariz area, near Imam Baqir Mosque, several Mujahedin of the Islamic Emirate lost their lives.”

For the majority of Afghans, a major consequence of the Taleban takeover of Afghanistan to their daily lives, as the Taleban point out in their statement, has been the sudden drop in civilian casualties and an end to the threat of conflict-related violence. However, not everyone has been able to stop fearing attacks. For Afghanistan’s Hazaras/Shias, the risk of violent death from ISKP and others unknown has yet to diminish, as they go to school, to work, to the market or to pray in congregation.[7] Other groups are also at higher risk of attack – Sufis, Salafists and Afghanistan’s Hindus and Sikhs.

UNAMA’s report also points to another type of violence facing Afghan civilians – allegations of the Taleban’s heavy-handed approach to journalists trying to report on incidents.

UNAMA recorded a number of incidents in which journalists were prevented from accessing sites of mass casualty IED incidents for reporting purposes, including through excessive or inappropriate use of force, threats and arbitrary arrests and detention. For example, on 11 February 2022, de facto security forces beat a number of journalists who were attempting to report on an IED explosion which had occurred in the Grand Mosque of Qala-i-Naw, Baghdis province. The de facto security force members reportedly also fired in the air to disperse the journalists and prevent them from filming at the scene of the incident.

The Taleban’s statement responded by saying these accusations of curbs on journalists’ reporting of attacks were actually attempts to protect reporters:

If there were some instances of violence against journalists on the fields, the reason has been to prevent journalist casualties in case of a potential follow up explosion because the enemy always tries to add to the number of casualties by carrying out explosions among journalists and first responders and such prevention might have led to some grievances.

Both UNAMA in its July 2022 report and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett, have alleged other threats to citizens from the state itself, including, in Bennett’s words from his February 2023 report, the Taleban government’s increased flouting of “fundamental freedoms, including the rights of peaceful assembly and association, expression and the rights to life and protection against ill-treatment,” his contention that it was “ruling Afghanistan through fear and repressive policies” and that the authorities’ “systematic violation of the human rights of women and girls” had deepened. (See AAN’s analysis of Bennett’s reports from September 2022 and February 2023; original reports can be found here). Taleban spokesperson Zabiullah Mujahed called the September 2022 report “biased and far from reality”, containing wrong information which had been misused. The rights of women and minorities and human rights were protected in Afghanistan, he said. (See reporting by to Bennett’s February report ToloNews in English here and in Dari here.)

UNAMA’s July 2022 human rights also documented a “clear pattern with regards to the targeting of specific groups by the de facto authorities.” These included former members of the ANSF, former government officials, individuals accused of affiliation with the armed opposition groups, ISKP, the National Resistance Front (NRF), journalists and civil society, human rights and women’s rights activists and those the Taleban authorities accuse of ‘moral crimes’. UNAMA also alleged that the Taleban’s general amnesty for former government officials, especially former members of the ANSF, had been violated. Mujahed called the report “inaccurate” and “propaganda.” There were no extrajudicial killings, he said, and if anyone did commit them, they would be punished based on sharia (see media reporting here).

What the various human rights reports point to is that, despite the end, largely, to armed conflict in Afghanistan and the falling away of the threat of conflict-related violence for most of its citizens, this is not yet a country at peace.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour

References

| ↑1 | UNAMA says that: “a large proportion of the attacks carried out over the period covered by this report do not have a clear link to a situation which can be qualified as armed conflict.” Nevertheless, it says that for the purposes of this report, ‘civilian’ “refers to anyone who is not, or is no longer, a member of the armed forces of the parties to an armed conflict and was affected by an attack which may or may not have a clear link to a situation which can be qualified as an armed conflict.”

It outlines the legal context on pages 7 and 8 of the report, saying: Widespread or systematic attacks directed against a civilian population (including religious and/or ethnic minorities) in which civilians are intentionally killed may constitute crimes against humanity. In addition, attacks deliberately targeting civilians and the murder of civilians are serious violations of international humanitarian law that amount to war crimes. International humanitarian law prohibits, and international criminal law criminalizes, attacks directed against places of worship which constitute cultural property. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | UNAMA’s last report on civilian casualties was its mid-year 2021 report (read all reports on the protection of civilians in conflict here). It also reported briefly on civilian casualties in its report, ‘Human Rights in Afghanistan 15 August 2021 – 15 June 2022’ (p10-12), published in July 2022. |

| ↑3 | In 2009, the year which previously had had the lowest number of civilian casualties, an average of 497 civilians were killed and injured each month (5,969 in total that year) while in the bloodiest year, 2016, there was an average of 954 casualties a month (11,452, in total that year). In comparison, since 15 August 2021, there has been a monthly average of 175 civilian casualties. |

| ↑4 | On average, 864 civilians were killed or injured each month from January to June 2021 (5,183 in total), rising to 1,196 civilians killed or injured in May and June 2021 (2,392 in total). |

| ↑5 | On its methodology, UNAMA says:

Civilian casualties are reported as ‘verified’ where, based on the totality of the information reviewed by UNAMA, it has determined that there is ‘clear and convincing’ information that civilians were killed or injured. In order to meet this standard, UNAMA requires at least three different and independent types of sources, i.e., victim, witness, medical practitioner, local authorities, community leader or other sources. Wherever possible, information is obtained from the primary accounts of victims and/or witnesses of incidents and through onsite fact-finding. UNAMA does not claim that the data presented in this report are complete and acknowledges possible underreporting given the limitations inherent in the current operating environment in Afghanistan. |

| ↑6 | Afghanistan’s Shia population includes Sayeds, Qizilbash and Farsiwan, with Hazaras by far the largest group. Among ethnic Hazaras, the overwhelming majority are Shia ‘Twelvers’ (believing in twelve divinely appointed imams after the Prophet Muhammad), but there are also smaller communities of Sunnis, including Ismaili Shias that parted ways with Twelver Shia based on their belief that Ismail the son of the sixth imam should have succeeded him as the seventh imam). |

| ↑7 | For more on how Hazara/Shia leaders have tried to position themselves to advocate for more decisive action from the Emirate to protect their communities from ethnic and/or sectarian attack, see Ali Yawar Adili’s February 2023 report for AAN, “The Politics of Survival in the Face of Exclusion: Hazara and Shia actors under the Taleban”. |

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 27 Jun 2023C

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign