Introduction

For twenty years, between 2002 and 2022, Helmand province ranked number one in poppy cultivation. A favourable climate allows for up to three harvests of opium poppy annually: the winter crop is usually planted in October/November and harvested in April/May, while the spring and summer crop seasons are far shorter and give poorer yields – April to July and July to September, respectively. During these two decades, each year Helmand accounted for more than half of Afghanistan’s total annual poppy cultivation (see graphs 1 and 2 in this AAN report).

Helmand is poppy-friendly not only because of its climate and vast agricultural lands, but because it has also served as the most important centre for Afghanistan’s opium trade: it is close to the rural areas of Pakistan’s Baluchistan province through which large amounts of opiates are smuggled out to the rest of the world. The Musa Qala bazaar, in particular, has been one of the biggest drug markets nationwide, attracting key drug traders and smugglers.

Additionally, before the takeover of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) in August 2021, Helmand was one of the most insecure provinces of the country. Insecurity fuelled poppy cultivation: as an annual crop whose buyers come to your farm (no need to pay bribes to get this crop to market) and which does not decay, if dried and stored properly, indeed keeps its value and can be used as savings, credit or to loan, it was the perfect crop for people living in insecure times. The former government and its international backers pursued efforts to stop it, but state corruption and ‘poppy interests’ in both the government and insurgency doomed these attempts to failure.

Opium poppy cultivation had, until last year, dominated agriculture in Helmand. For decades, other crops, such as wheat and maize, were negligible. Those districts of Helmand with a warm climate, such as Nad Ali, could grow poppy all year round. The main harvesting season, between April and May, attracted seasonal workers from other provinces like Ghazni, Zabul, Wardak, Paktia and Paktika. One of the authors even observed in spring 2019, Afghan refugees and Pakistanis coming to Helmand, especially to Nad Ali, to labour in the poppy fields (see this AAN report).

The United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (UNODC) estimated in 2022 that opium poppy was cultivated on a fifth of the arable land in the province (see UNODC survey here). However, in 2023 – a year after the Emirate’s ban – Helmand had slipped to 7th place in the rankings (behind Badakhshan, Kandahar, Daikundi, Uruzgan, Baghlan and Nangrahar). (A table showing provincial rankings and the percentage change in area under cultivation compared to 2022, based on data from David Mansfield and Alcis, can be seen in this AAN report from November 2023). It was a repeat of the first Emirate’s ban, when previously dominant Helmand was forced to stop cultivating, whereas Badakhshan, then under Northern Alliance control, kept growing opium poppies. This time, both provinces are under IEA control.

The ban was expected to hit particular segments of the population very hard: small farmers whose holdings are too small for a crop like wheat to provide enough income to support a family,[1] farmers who are landless and either rent land or work as sharecroppers and daily labourers. It was also expected to have a depressive effect on the local economy on businesses indirectly dependent on income from poppy. To better understand how the ban has affected these people, AAN conducted ten interviews in four districts of Helmand province – Marja, Nad Ali, Greshk and Musa Qala. The interviewees were: six farmers, two shopkeepers, a tailor and a mechanic (all male). AAN targeted people from households who were struggling to find employment, as well as farmers who had tried to switch to alternative crops.

The report is structured in five sections, each corresponding to a question. The first section offers the background information collected from various sources and descriptive accounts from our interviewees about how the ban has been implemented. The second deals with the implications of the ban on opium prices; it includes background information collected from various sources and the first-hand accounts from our interviews. The third and fourth questions asked our interviewees how they personally had been affected by the ban, either as farmers and sharecroppers or as small business owners. The final question found out from farmers if they had sown alternative crops and how this had worked out.

How has the ban been implemented?

The ban on the cultivation and production of opium and the use, trade and transport of all illegal narcotics was announced in April 2022, at the beginning of the main opium harvest season. The IEA allowed farmers to harvest the ‘standing’ opium crop, that was already in the ground, but then launched initial eradication efforts targeting the second and third harvests in Helmand, as illegal narcotics expert David Mansfield explained in this AAN report from June 2022:

The authorities didn’t touch the standing crop – the one planted in the fall of 2021 – that was only a week or two from harvest as that would have provoked widespread unrest so close to the harvest season and after farmers had invested considerable time and resources in their poppy fields. … Rather it was the second and even third crops of the season that was the focus of the Taliban’s eradication efforts over the spring and summer of 2022. Typically, small and poor yielding, these crops were not well established and were a much easier target for the authorities. Much was made of these efforts with videos of crop destruction posted on social media by the Ministry of Interior as well as by individual commanders and farmers.

The IEA then began to enforce the ban nationwide in the autumn of 2022 when farmers normally sow the seeds to harvest in the following spring. Just how severely became evident from satellite imagery analysis released in 2023. In Helmand, Mansfield and Alcis found, poppy cultivation had plummeted from 129,000 hectares in 2022 to 740 hectares in April 2023. However, other provinces managed to at least partially escape the worst of the authorities’ eradication efforts and, as mentioned earlier, in Badakhshan, farmers had been allowed/able to increase their cultivation (see AAN reporting here). UNAMA reported on 28 February 2024 in its regular quarterly report to the UN Secretary-General that “available evidence from the field indicates that some farmers in Badakhshan are cultivating opium, in particular in remote areas.” It also said that, “similar reports were received from northern Kandahar and Nangarhar.”

The owner of a small landholding in Greshk district who used to cultivate poppy on a part of it told AAN in early December 2023 that a group of IEA police, along with the district head of police, had come to the area to make sure poppy was not being grown in his village. He said they were even going inside residential compounds in search of poppy. The inspection was widespread and as a result, he said farmers switched to alternative crops:

The people in Greshk switched to other crops. But, for example, cumin, we didn’t [switch to] that because we’re unfamiliar with it. We were also cultivating cotton in the past, but we don’t have that much water now. The water table has fallen almost to 70 or 80 metres and we can’t draw water up with the solar panels, because when the water is that deep you need more energy than the solar panels supply. The panels we leased out are not enough for pulling water from a deep level.

A small landowner from Marja district said they began cultivating other crops, but because of the drought and lack of water, they had not yielded enough profit to cover household expenses.

Just after the announcement of the ban on poppy cultivation, we switched to cultivating other crops, like wheat, cumin, coriander and cotton. But none of those can make the money we were making out of poppy. [Money we had saved from previous opium harvests] was enough, though, for us to run our household on, even though the opium price [when I sold that opium] was much lower before the ban.

A 42-year old farmer from Musa Qala district said he had also switched to other crops, but the drought had affected his harvest. Without rain, he said, the wheat yield was poor. In a sign of absolute desperation – no one sells their means of work unless they absolutely have to – he had sold his solar panels because he could not get a loan:

When the ban was announced, I didn’t sow poppies. Instead I sowed wheat. The wheat didn’t grow well because there was no rain and when there’s no rain you can’t get a good harvest of wheat from your field. In that year, I was only able to feed my children for nine months. I had to feed them, so I sold my solar panels. I was obliged to do this, because there was no alternative. In the years when the poppy crop wasn’t banned, you could get a loan from shopkeepers and others, but now everyone thinks that the source of income has dried up and the shopkeepers won’t sell on credit.

The IEA tightened its grip even more in October 2023, just ahead of the new sowing season, when it issued a new penal code on the cultivation, trafficking, trade, collection, etc of drugs and other psychoactive substances such as alcohol (see here for the Pashto original and an English translation of the law by Alcis). Under this law, opium and cannabis farmers are also subjected to punishment – six months in prison for cultivating these plants on less than half a jerib of land, nine months for half a jerib and one year for more than one jerib.

Regardless of the new law, some farmers decided to sow opium, especially where the growing plants are hidden from passers-by, for example, sowing opium poppy in amongst wheat, cumin, or hidden inside the confines of their own compounds.

AAN interviews indicated that a small number of opium farmers in some districts had been imprisoned for short periods of time, albeit less than allowed for by the October 2023 law. A 28-year-old small landowner and sharecropper from Nad Ali district described how the authorities had searched people’s compounds to make sure poppy was not cultivated. “When they find poppy, they plough the crop into the soil or eradicate it with herbicides and put the owner in prison for a few days.”

Another farmer in Nad Ali district said that he, himself, had been detained by the authorities in February 2024 after his children had sowed some poppy on the borders of the family’s barley crop. He was held for a day. The primary court had asked him if he was aware of the decree of the amir. He said he told them he was aware of it, but unaware that his children had sown poppy in his barely field. The judge told him that for a half jerib of poppy he could be imprisoned for six months. The farmer was released, he said, thanks to a guarantee from the elders. The IEA sprayed his poppy, destroying it.

An interviewee in Greshk district said that, last November, during the poppy sowing, the IEA had arrested some people and imprisoned them for between one and three months. He thought this was intended to frighten other farmers into not growing poppy. Lately, he said, no one had been arrested. Another man, from Musa Qala, said that there, opium had been sown inside compounds, but that officials had eradicated it as soon as they found out about it.

From what sources in the province told AAN, enforcement of the new law and eradication have taken place, but it has been sporadic and spotty and not evenly applied in all districts.[2] However, it is evident that it had worried farmers that enforcement might become very serious in the near future and that was enough, it seems, to curb their flouting the ban.

What effect has the ban had on prices?

UNODC estimated that the total income made by farmers selling the 2023 opium harvest declined by more than 92 per cent compared with 2022, from more than 1 USD billion to just over 100 USD million. However, anyone possessing an inventory of opium paste who had been able to afford to keep it, could now sell it for windfall profits (see this AAN report) because of the price rise since the IEA takeover. Prices began to shift upwards in August 2021 and by the following spring were significantly higher, UNODC said. In November 2022, Mansfield said, “opium prices had risen to almost 360 USD per kilogram in the south and southwest, and 475 USD per kilogram in the east – triple what it had been in November 2021.” By August 2023, they were as high as 408 USD a kilogramme and this, said UNODC, was a “a twenty-year peak.” It surpassed even the price hike that followed the first IEA ban when by 2003, a kilogramme of opium paste was selling for 383 USD.

Prices only continued to rise. In December 2023, Mansfield reported, opium prices had reached as much as 1,112 USD per kilogramme in the south and 1,088 USD per kilogramme in Nangrahar (see this tweet). An interviewee from Nad Ali district told AAN that, in December 2023, one man (4.5 kilogrammes) of opium was worth 1.4 million Pakistani rupees (4,830 USD) in the local market. This is a three-fold increase in value in only one year; a man of opium had been selling for 1,620 USD in November 2022.

However, it seems that prices have begun correcting themselves. In early February 2024, an opium trader from Nad Ali told AAN that one man of good quality opium was worth 900,000 Pakistani rupees (3,220 USD). He said a fall in prices had been triggered by the Iranian currency depreciation. He also said that poppy grown in some provinces of Afghanistan in 2023, as well as in Baluchistan province of Pakistan, had eased supply, also reducing the price.

The hike in prices undoubtedly profited traders and those farmers who had an inventory to sell. One farmer from Nad Ali, who had been able to afford to wait to sell his standing harvest from the crop planted before the ban came into force, described his good fortune:

My life is good. Poppy was fulfilling 80 per cent of my yearly expenses before the ban. After the ban, an extraordinary change came in my life. I’d kept the poppy paste and its price hiked dramatically. Believe me, if I’d cultivated poppy for 20 years, I wouldn’t have made as much money as I made after getting only that one harvest of poppy following the ban. I kept that [paste] and when it soared in value, I sold it.

It has also become clear that, while the IEA has focused on preventing the cultivation of opium in Helmand, trade in opium and its products, especially in major markets like Musa Qala, has continued uninterrupted. In their June 2023 report, Mansfield and Alcis said there were few restrictions on trade nationwide (see also this video of opium paste production that was widely shared on Twitter in February 2024 and was reported as recorded in summer 2023). In September that year, an eye-witness in Helmand told AAN, it was still “business as usual” there. However, by November, Mansfield and Alcis reported “growing evidence that the Taliban are ratcheting up the pressure on those involved in the opium trade,” although, they also said the only route that had not experienced a rise in smuggling costs is the journey via Bahramchah “possibly reflecting continued privileges afforded to those in Helmand.” It was a “dynamic environment,” they warned, and “like the ban on cultivation … reflects the uneven nature of Taliban rule in which some groups are favoured over others.” AAN tried to find out more about the situation currently: several people, in Marja, Nad Ali and Musa Qala districts, all confirmed that opium continues to be freely sold in local markets.

How has the ban affected farmers and daily wage labourers?

Poppy cultivation was a major employer in Helmand; it provided almost 21 million days of work for those weeding and harvesting and 61 USD million in wages in 2022, according to Mansfield (cited in this AAN report). This is why the ban has so bitterly affected poor farmers and daily wage earners, as the interviews that AAN conducted with farmers and sharecroppers show.

Many, such as the 28-year-old small landowner and sharecropper from Nad Ali, have found themselves unable to provide the basics for their families.

My brother and I are now jobless. We were both working on our land as well as on other people’s at weeding or harvest time. Poppy was our life. Even in a year that was bad for poppy, and it suffered from diseases, we could still at least meet our basic expenses. In good years, for example, a rainy year, we could meet 100 per cent of our family expenses from our own poppy harvest. We could even save some money. Now, we don’t know how to feed our family. … In the past, sometimes, if we made good money, we’d buy a car or a motorbike. Believe me, last summer, we sold our car because we couldn’t afford food and couldn’t make any money from our land.

Around 17 people from his village, he said, had left for Iran. If the situation continued, some men from his family would also have no other choice but to leave for Iran or other country.

A similar story was shared by a 32-year-old landless farmer from Greshk district, who used to rent land. His family, he said, could make around 70 per cent of their yearly household expenses from selling their poppy harvest, growing some wheat as well, just enough to feed the family. They also worked in other people’s poppy fields to meet their needs. Now all that is gone. The farmer said he had been able to keep going with a nursing course – he was due to take his last semester and a classmate had paid the 6,000 afghani fee. He should start to be able to earn an income as a nurse soon, but other than that, he said the family was in economic distress. Some relatives were hoping to migrate to Pakistan or Iran.

For the last six months my elder brother has been trying to convince my parents to let him travel to Iran, but my parents, especially my father, insists we should wait: he keeps telling us the situation for Afghans in Iran is also not good and the route is extremely risky.

Another man, a 40-year-old Greshk district, who had a small amount of land, but no water on it, so had rented land, said he and all his brothers were now jobless. His brother, he said, had “travelled to Iran with the help of a human trafficker” and that after he arrived, had first to earn money to pay back what he had borrowed for the trip and after that, would be able to send money home:

We sent our brother around five months ago. After spending three months there, he sent us some money, which helped us a lot with food for the household. But we don’t want him to be too long away from his family – he has a wife and two children. We wish there were jobs in our country and those who are dear to us could come back home and work here.

The ban on growing poppy, he said, had “paralysed his family”:

Poppy was the main crop we were cultivating. Sometimes we’d cultivate wheat on two jeribs (around half a hectare) and sometimes only poppy. The poppy harvest was more than enough for our annual household expenses. It also provided us with savings.

A small landowner from Marja district, who is 31 years old, told AAN that the ban had had severe consequences for his community, as well as himself: “Only this year, 37 individuals who were daily wage earners or farmers in our village left for Iran to work there in order to feed their families.” Before the ban, only a few men from his village had had to travel to Iran. His brother, he said, had been trying to get to Turkey from Iran, so far, unsuccessfully:

There are no jobs in our province since the ban. My elder brother went to Kandahar and then to Kabul to work there, but he didn’t find any work. He returned home disappointed. Finally, last spring, he went to Iran. After four months, he called me to say he wanted to travel on to Turkey. He’d heard from his friends that there were good jobs there and a good chance to travel further, on to Europe. Though, I didn’t agree, he was insisting. Finally, he started the journey with two friends. After around 40 days, he called me from Iran saying he’d been arrested by Turkish police and had been in prison for 28 days. He’s begun working in Iran again. He told me that when he earns some money, he’d try again for Turkey.

In other districts, too, interviewees told us about labourers and farmers who had travelled illegally to Iran, with some also attempting the journey onwards, west to Turkey.

The ban has also taken toll in other ways. A resident of Nad Ali said some people in his district faced “mental problems” because they were so worried about how to feed their families. One interviewee, a 42-year-old farmer from Musa Qala district was quite open about his depression and worries:

I am very depressed. I don’t know how I could feed my children. I have 30 jeribs [six hectares] of land. I had dug two tube wells. One is dried up, the other still has water in it – I’d installed solar panels on it – and was cultivating poppies on my land, and some wheat as well. The poppy was fulfilling all the yearly expenses of my family. My life was comparatively good.

Now, I’ve rented some land along with solar panels installed on a tube well. There’s a rule here, when you rent some land, you don’t have to pay the owner of the land money. In my case, I grew wheat and cumin, and I give them the wheat once it’s harvested. But there’s not much water in the well, not enough for both crops. I’m lost in my worries… how I will feed my children? I don’t have sons old enough to send to Iran or Pakistan to work.

How has the ban affected small businesses?

We also interviewed four small business owners, one in each of our targeted districts, who pointed out that the ban had also had a knock-on effect on them. Three reported a significant loss of income since the ban. A 28-year-old small grocer from Marja said his daily turnover had fallen almost threefold, from around 100,000 Pakistani rupees (360 USD) before the ban to about Afs 10,000 (135 USD) now.[3] He had lost far more by giving customers credit.

I’m really badly affected. I used to give my customers food and non-food items on credit one season [for them to pay me] the next. The year before last, they paid me back, but last year they didn’t. I was thinking my customers would receive the money after the harvest of wheat, cumin and other crops, but unfortunately, they didn’t make enough to pay me back. The harvest was bad because of the lack of water. The water level is now very low. It’s gone down to 100 meters. I had 50 customers and they were buying their household requirements from my shop on credit. I lent around Afs 2.5 million (USD 34,450). They were good customers and my shop was running well because of their custom. Now, they don’t have money to pay me. Some of them have even travelled to Iran and Pakistan for work. From around 50 households in our village, around 35 people have travelled to Iran and Pakistan for work.

A tailor in Nad Ali district said the ban had cost him many customers. Nowadays, he only sells new clothes around Eid:

We used to make clothes for those working in the poppy fields at different times, for example, at weeding and harvesting times. Now, they don’t come for new clothes because they don’t have the money.

One man, however, found the ban has created opportunities. A 35-year-old mechanic from Musa Qala district reported:

Personally speaking, my work has flourished. Because, in the past, when people got their harvest, they’d buy new motorbikes and the new motorbikes didn’t need repairing, but now they’re repairing their old ones, and that’s increased work for me and I’m earning more than before.

Are there alternatives to growing poppy?

Many farmers said they had tried to switch to other crops in 2022, but faced many problems because they were unfamiliar with new crops, like cumin. None mentioned support from the government. Some said they had had some support from NGOs and UN agencies to help with the transition to new crops, although it was not really sufficient. One small landowner from Marja district said an unnamed NGO had given him some chemical fertilizers and wheat seeds – two sacks of wheat, 100 kilogrammes in total, and two sacks of ‘black’ and ‘white’ chemical fertilizer, each weighing 50 kilogrammes.[4]

In Greshk district, a 32-year-old farmer received a similar amount of aid, which according to him, was far from enough:

There’s an NGO which is providing people with wheat and chemical fertilizer, but that’s not for all. For example, they gave some 50 kilogrammes of wheat and 100 kilogrammes of chemical fertilizer to our village. The NGO had merged three households and the households then needed to divide aid among themselves. Actually, this aid didn’t fulfil the requirements of a single family. This kind of assistance isn’t working at all.

The 28-year-old former opium farmer from Nad Ali district whose family had switched to cultivating wheat and cumin and cotton and some vegetables in the spring, said:

We were given an aid card, valid for six months. An NGO was providing food aid to the people. We received the food for four months and for the other two months we weren’t given that aid. We didn’t know the reason.We were also provided with two sacks of chemical fertilizer and a sack of seeds (wheat). The aid wasn’t given to all people in the district. It wasn’t helping, because we usually grow on more land, and this wasn’t enough. The seeds the NGO gave to the people also weren’t suited to the climate of Helmand and didn’t give a good harvest.

Some farmers bought seeds on loan, like a 40-year-old farmer from Greshk district, who had to pay double the going price of cumin seeds because he bought them on credit:

We switched to other crops like wheat and cumin. But we’ll have to pay the money back for the seeds after the harvest. For a man of cumin, we had to pay 4,000 (56 USD) because we bought them on credit, instead of the normal, market price of Afs 2,000 (28 USD). … The cumin and wheat won’t be enough to meet our expenses.

He said that in his district an NGO employs people to clean water canals in irrigated areas or to repair unpaved roads in desert areas, paying them 9,000 Afghani around (USD 125) per twenty working days.

Alternative livelihoods projects, ie projects that support farmers and communities to transition to licit crops and improve food security and household income, what has come so far is evidently not enough. There has been no government support and as many interviewees said, NGO assistance in the form of seeds, chemical fertilizer or free food is also not enough to change the fundamental economics of the ban: there is no short-term alternative to poppy, that brings in the same income for the same area of land and provides labouring jobs for the poorest.

The idea that donors might restart alternative livelihood projects, given the multiple and multi-year failures of this concept under the Islamic Republic, has worried many, among them United States Institute of Peace (USIP) economist, William Byrd, who was also critical with the way the IEA introduced the ban, calling it bad for Afghanistan and bad for the world. He wrote:

Phasing out Afghanistan’s problematic drug economy will be essential over the longer term — not least to contain widespread addiction within the country. But this ban, lacking any development strategy and especially at a time when the economy is so weak that displaced opium poppy farmers and workers have no viable alternative sources of income, is not the right way to start on that path.

Byrd’s report, published in June 2023, also correctly forecast that:

There will probably be a counter narcotics-driven, knee-jerk response that the effectively implemented Taliban opium ban is a good thing. However, history amply demonstrates that banning opium in Afghanistan by itself is not sustainable, nor does it address the drug problem in Europe and elsewhere. And it won’t stop rampant drug use within Afghanistan.

More short-term humanitarian assistance may be needed, he wrote, but that should be recognised as a ‘band-aid’ measure. Rather, [s]ome forms of basic needs rural development aid could be helpful – agricultural support, small-scale rural infrastructure, income generation, small water projects, investments in agro-processing and marketing, and the like.” However, “[c]ustom-made, standalone ‘alternative livelihoods’ projects should be avoided, especially if designed, overseen or implemented by counter-narcotics agencies, which lack development expertise.” It is broader rural development, he insists, “that will over time make a difference, as part of a healthy, growing economy that generates licit jobs and livelihoods opportunities.”

It is also worth noting that for Afghanistan, as a whole, there is no viable alternative to poppy. Opiates have generally brought in the equivalent of around 10 to 15 per cent of Afghanistan’s licit Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the value of all the goods and services produced in the country in any one year. Illegal narcotic production is one of the very few sectors where Afghanistan has a comparative advantage. Given that the economy contracted by a fifth in 2021 and has continued to contract since, albeit at a lower rate, poppy cultivation will be sorely missed at the macro-economic level, as well (see World Bank reporting from October 2023 and AAN analysis for discussion of the wider economic travails facing Afghanistan).

The way ahead?

Afghans, nationwide, have been struggling immensely, because of food insecurity, lack of jobs and living in an internationally isolated country. The ban on poppy cultivation has only exacerbated the crisis for many of those who were directly or indirectly dependent on the opium economy, who previously had enjoyed a far more secure life. Many are now facing poverty, debt and feeling they need to migrate. Many are faced with depression and anxiety and are at their wits end.

The government did nothing to prepare farmers and communities for the harm the ban on cultivation would do to them. It announced the ban without any planning or consultation with experts or potential donors who might have been able to help manage the transition from illicit to licit crops. In recent months, however, calls from ministers and others for international attention and support became more frequent, for example, at a meeting between the IEA and EU held on 7 February 2024, the acting Deputy Minister of Interior for Counter-Narcotics Abdul Haq Akhund asked EU Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas Nicholson “to cooperate with Afghanistan in supporting and treating drug addicts and farmers” (see media reporting here).

IEA efforts to curb illicit drugs have not been publicly praised, but they have been recognised, for example, in the UN’s Independent Assessment on Afghanistan. The IEA, it said, had “demonstrated significant progress in their announced campaign to reduce and eventually eliminate the cultivation, processing and trafficking of narcotics.” (see this AAN report). The US State Department was more terse in its statement from 31 July 2023. It only “took note of reporting indicating that the Taliban’s ban on opium poppy cultivation resulted in a significant decrease in cultivation” and “voiced openness to continue dialogue on counternarcotics.”[5]

As yet, there has been no significant international aid given to Afghanistan to mitigate or, at least, soften the economic blow the ban has caused, although the UN’s Independent Assessment did say that “many stakeholders expressed interest in exploring greater international cooperation in this area [counter-narcotics], in particular on alternative crops and livelihoods for the hundreds of thousands of Afghans that have relied on the production and trade of narcotics for income.”

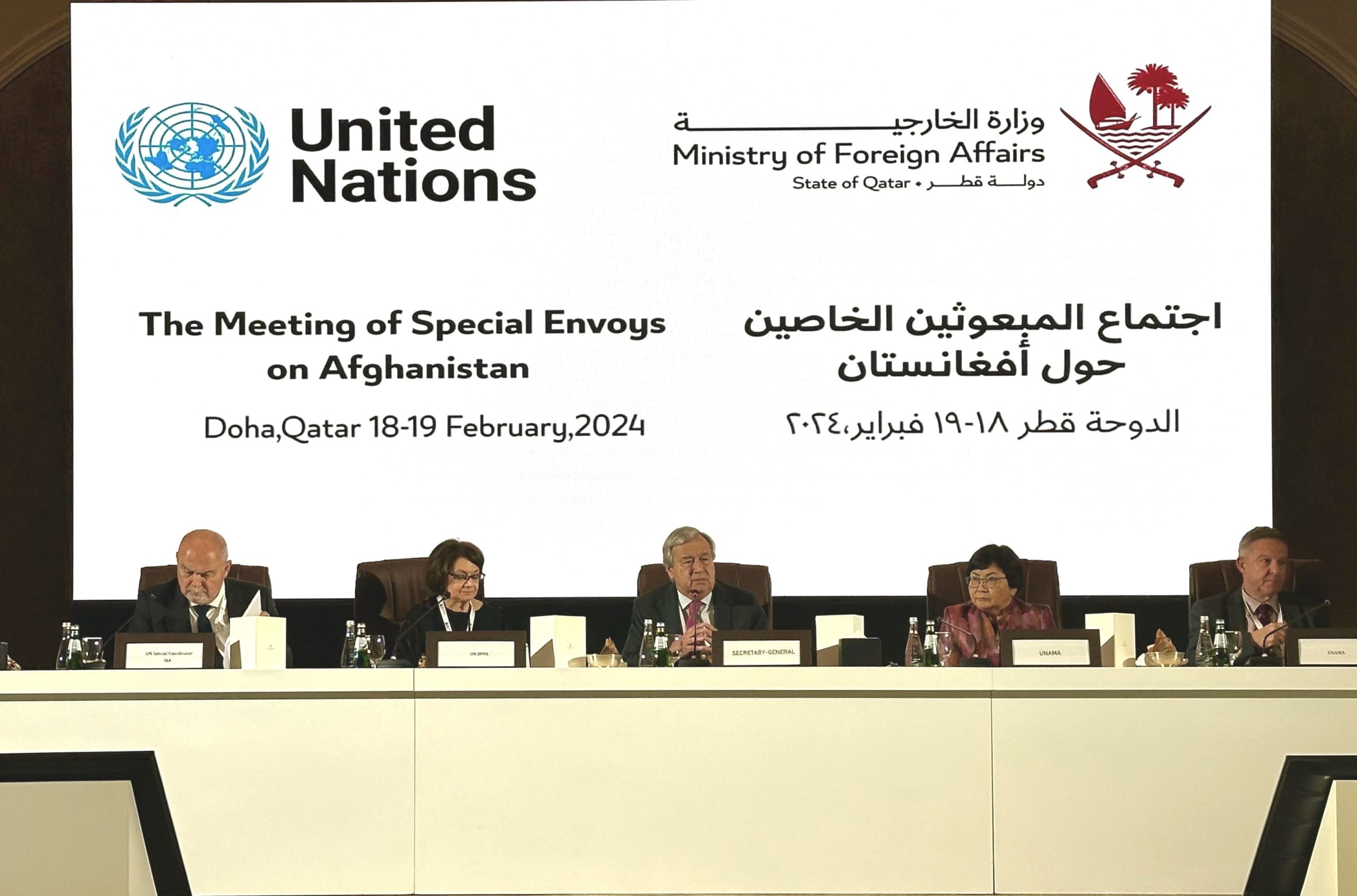

There have started to be higher-level moves to get a conversation going between the IEA and international donors and neighbours. For example, the Working Group on Counter-Narcotics, established in the mid-September 2023 and co-chaired by UNAMA and UNODC, had met the Kabul-based diplomatic corps (among other with Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, the EU) and the acting Deputy Ministers of Interior for Counter-Narcotics, and for Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock twice, on 13 November 2023 and 31 January 2024 (as reported by UNAMA in its February 2024 UN Secretary General). “At the meetings,” UNAMA’s report said, “the de facto authorities shared their achievements and challenges including the lack of resources, asking for international attention and support.”

In that light, there has been another interesting recent meeting. Acting Deputy Prime minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar Akhund and former Executive Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime Pino Arlacchi met in Kabul on 4 March, reported IEA’s Ministry of Economy. Arlacchi was head of UNDCP, a predecessor of UNODC, from 1997 to 2002. According to ToloNews, quoting Baradar’s office, Arlacchi had said that “an international conference in Kabul” was going to be organised “soon, aiming to garner financial support for implementing alternative crop programs in Afghanistan through international cooperation.”[6] He also asserted that “the international community has responsibility to assist in providing alternative livelihoods for Afghan farmers.”

It remains unclear who Arlacchi actually was representing at the meeting, or whether it was just his own personal initiative. The current UNODC Director of the Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, Jean-Luc Lemahieu, said they had known nothing about the planned visit: “We were surprised too,” he told AAN. “And I can confirm that he has no formal links with UNODC since leaving the organisation in 2002, and to my knowledge, none to the UN at large.”

Donor support for Afghans hurt by the ban on opium cultivation may come, but it will come late for those farmers already hard hit and probably not at all for day labourers. The ban on opium cultivation has created a huge hole in the economy of a province like Helmand that will not easily or quickly be filled.

Edited by Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | In Afghanistan, wheat is generally grown as a subsistence staple, not a cash crop. The comparative price with poppy shows why it is not an alternative, especially for small farmers: UNODC figures for 2023 suggested farmers could make USD 770 per hectare for wheat, compared to USD 10,000 for poppy. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The IEA official narrative is of a strong and determined counter-narcotic effort. The acting Deputy Minister of Interior for Counter-Narcotics boasted, on 2 February, that during the past two years more than 2,000 counter-narcotics operations were conducted across the country, with over 1,100 drug production factories destroyed and more than 13,000 individuals arrested on charges of the production, sale and trafficking of illegal drugs. See the UNAMA regular quarterly report to the Secretary General from 28 February 2024. |

| ↑3 | The IEA banned trading in Pakistani rupees and this is why the interviewee expressed his earnings after the ban in afghanis. |

| ↑4 | He did not know the NGO’s name, but this UNODC report said that since March 2022, it had been implementing an alternative livelihoods and food security project in Lashkargah, Nad-e Ali and Nahr-e Siraj districts in partnership with the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR).

UNAMA also reported in its last report to the UN Secretary General, published on 28 February 2024, that UNODC alternative livelihoods support provided to former opium farmers “led to income generation for farmers of 129 USD per month from dairy products and 1,029 USD per season from pistachio nurseries.” The report does not specify geographical location for these farmers, nor does it give the exact number of farmers who benefitted. It is also not clear over which period of time these famers received the income. |

| ↑5 | See here about technical talks on counter-narcotics between the IEA representatives and the US held on 21 September 2023 in Doha. |

| ↑6 | Tolo news reported that “”They [the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in Afghanistan] plan to hold an international conference in Kabul in the near future and attract international financial support for the alternative cultivation of poppies to Afghan farmers through this conference.” (brackets in original). Mullah Baradar’s office reported that Arlacchi had “expressed the intention to organize an international conference in Kabul soon, aiming to garner financial support for implementing alternative crop programs in Afghanistan through international cooperation.” |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign