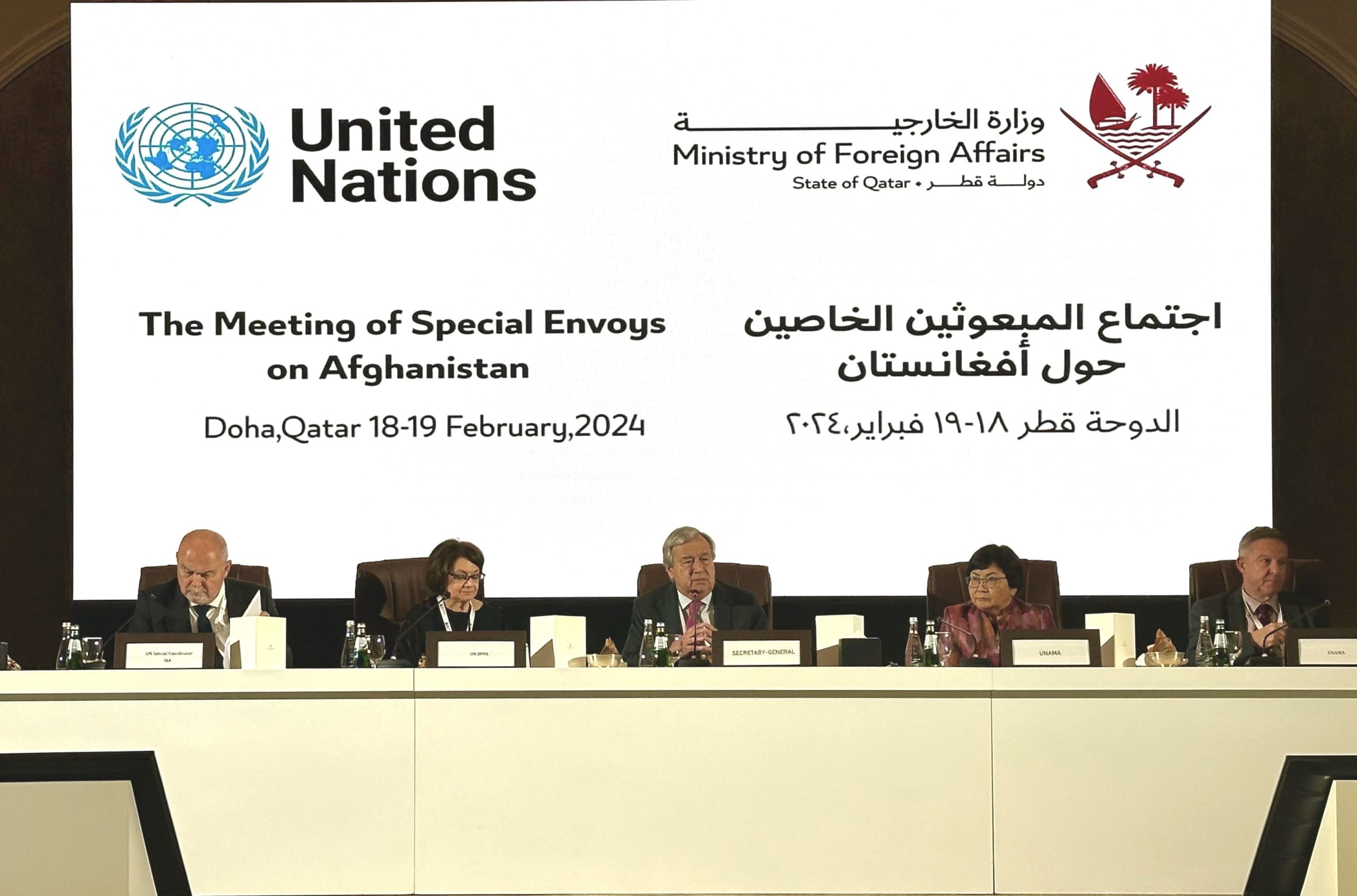

The second meeting of the Special Envoys on Afghanistan held in Doha, Qatar, on 18-19 February 2024 took place without a much-anticipated delegation from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA); whether it would go or not was an outstanding question right up to the final hours before the gathering began (see AAN reporting). The meeting was followed by a closed-door session of the United Nations Security Council, ostensibly for a briefing on the outcome of the gathering in Doha, especially with regard to the controversial decision to appoint a UN Special Envoy for Afghanistan.

In this report, we look at what, if anything, were the outcomes of the meeting in Doha and the subsequent session of the UNSC. We try to make sense of what the apparent emergence of a regional block of nations might mean for future international engagement with Afghanistan. We try to make sense of the IEA’s position concerning the special envoy and why, in the end, it decided against participating in the meeting in Doha. We try to make sense of what Afghans themselves are saying about the world’s engagement with their country. Finally, we look at what might happen in the future and, if there is no progress over an UN-appointed special envoy, whether Afghanistan’s foreign interlocutors will be able to make headway on other, arguably more important, issues that would help improve the lives of the Afghan people.

Why did the special envoys meet in Doha?

On 16 March 2023, following weeks of complex negotiations over Afghanistan and the annual renewal of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan’s (UNAMA) mandate, the UN Security Council passed two resolutions on Afghanistan – one (Resolution S/RES/2678(2023) extended UNAMA’s mandate until 17 March 2024 and another (Resolution S/RES/2679(2023) asked the Secretary-General to conduct an independent assessment which would provide recommendations for “an integrated and coherent approach among different actors in the international community in order to address the current challenges facing Afghanistan” (see AAN report which looked at the politics behind this move in detail). On 25 April, it was announced that the UN Secretary-General had appointed senior Turkish diplomat Feridun Sinirlioğlu as the Special Coordinator to conduct the assessment. It was just after this, that Guterres hosted the first meeting of special envoys in Doha, to which the Emirate was not invited (see AAN’s reporting about that gathering, held on 1-2 May 2023). Guterres’s aim with the first Doha Special Envoys meeting was “to reinvigorate international engagement around key issues, such as human rights, in particular women’s and girls’ rights, inclusive governance, countering terrorism and drug trafficking” (see UN press release). The special envoys also discussed their expectations from the independent assessment report.

The Independent Assessment Report, submitted by Sinirlioğlu to the Security Council on 10 November 2023, identified five key issues and priorities: human rights, especially of women and girls; counterterrorism, counternarcotics and regional security; economic, humanitarian and development issues; inclusive governance and rule of law and; political representation and implications for regional and international priorities (concerning the lack of recognition of the IEA).

It made several recommendations for a “performance-based roadmap” for advancing its stated goal – “An end state of Afghanistan’s full reintegration into the international system.” These include engagement with the IEA, starting with the economy, which would see international assistance expand to include development assistance, particularly in the banking sector; security cooperation, including on counterterrorism and counternarcotics; political engagement, including an intra-Afghan dialogue and on Afghanistan’s international obligations.

Finally, it proposed three mechanisms to coordinate these efforts: a UN-Convened Large Group Format (which already exists – this was the group which met in Doha in May 2023 and also on 18-19 February); a smaller and more active International Contact Group and; an UN Special Envoy, complementary to UNAMA which would focus on “diplomacy between Afghanistan and international stakeholders as well as on advancing intra-Afghan dialogue.” It has been that last mechanism, the appointment of a special envoy, which has ended up eclipsing the rest of the Assessment, with the Emirate logging its strong opposition to the idea from the very start (see AAN’s analysis of the Assessment report and the debate around it).

On 29 December, its last working day of 2023, the Security Council adopted Resolution 2721. It encouraged “member states and all other relevant stakeholders to consider the independent assessment and implementation of its recommendations” and asked the Secretary-General to “appoint a Special Envoy for Afghanistan” (see AAN analysis). Importantly, the Resolution was adopted by 13 votes in favour, with China and Russia abstaining, rather than using their power as permanent members of the Security Council to veto it (see UN press release). The Resolution welcomed Guterras’ initiative to organise the second Doha meeting and requested him to appoint “in consultation with members of the Security Council, relevant Afghan political actors and stakeholders, including relevant authorities, Afghan women and civil society, as well as the region and the wider international community” a Special Envoy. The second meeting of the Special Envoys on Afghanistan in Doha on 18-19 February 2024 should be seen in light of this requirement, as well as being part of the process that started with the extension of the UNAMA mandate and the UNSC asking for the independent assessment in March 2023.

What happened at Doha II

Even as 25 special envoys and representatives on Afghanistan started arriving for the Doha II meeting, the IEA’s participation was still very much in doubt.[1] The Emirate’s foreign ministry, which initially asked for clarifications on the agenda and invitees (see media report), finally released a statement, the day before the gathering was due to begin, outlining its conditions for attending the meeting. It noted that while the meeting was a good opportunity to have “frank and productive dialogue,” the IEA had two conditions for its participation: 1) that it would be the only representative of Afghanistan, meaning that civil society representatives and members of opposition groups would not be present; and 2) that its delegation would meet the UN at a very senior level. Reportedly, the ask was for a meeting between IEA acting Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi and UN Secretary-General António Guterres. These conditions were rejected by Guterres, who told reporters on 19 February:

I received a letter with a set of conditions to be present in this meeting that were not acceptable. These conditions, first of all, denied us the right to talk to other representatives of the Afghan society and demanded a treatment that would, I would say, to a large extent be similar to recognition (see video here and transcript here).

A document, unpublished but widely distributed (AAN has seen a copy), which is purported to be notes from a briefing by an ‘expert on Afghanistan’ who was present in Doha, also lists other difficulties for the Emirate, to do with protocol and what the agenda said about the UN’s view of the IEA’s status: special envoys had been given plenty of time to meet the Secretary-General, while Afghans in general had not, and adding insult to injury, the IEA appeared to have been accorded the same status as Afghan civil society actors. Whatever the reason behind the decision not to go to the meeting, the gathering in Doha proceeded in the IEA’s absence. Many believed an opportunity for rapprochement between Kabul and the West had been missed or, for those opposed to engagement, narrowly avoided.

While not much is known about the sessions at Doha II, which were held behind closed doors, AMU TV, whose CEO, Lutfullah Najafizada, was among the civil society representatives present, did post the following schedule:

The two-day event includes four meetings. Monday’s agenda begins at 09:00 am (Doha time) with remarks from the UN Secretary-General, followed by a 15:30 meeting between special envoys and Afghan civil society representatives.

A scheduled 17:30 meeting with the Taliban delegation was canceled following their refusal to participate. The day’s schedule includes:

- Special envoys of countries and organizations meeting.

- Working meeting among special envoys.

- Remarks by the UN Secretary-General.

- Meeting between special envoys and Afghan civil society representatives.

- Canceled meeting with the Taliban delegation.

On their first day in Doha (18 February), the special envoys’ time was taken up with a throng of bilateral meetings between special envoys from various countries as well as consultations between foreign delegations and Afghan civil society representatives.[2] The IEA had been vigorously opposed to their participation, a fact which was stressed by its envoy to Qatar, Muhammad Naeem Wardak, who told BBC Persian that the Emirate was the sole representative of the Afghan people and inviting other people is “against all principles and regulations.”

In line with the wishes of the Islamic Emirate, Russia refused to participate in meetings with “so-called Afghan civil activists,” saying they had been selected “non-transparently, behind Kabul’s back,” according to a statement issued by its embassy in Kabul (see the Russian News Agency Tass). China and Iran also, reportedly, refrained from meeting civil society representatives, but did not issue a statement about it (see ToloNews). The UN Secretary-General criticised Russia’s decision during his press conference, held after the meeting:

Indeed, it is true that the Russian Federation issued a communiqué saying that we should not meet the civil society. I am terribly sorry, but I am in total disagreement. I think it will be very important to meet with the de facto authorities. But I think it’s also very important to listen to other voices in the Afghan society.

This sentiment was echoed by US State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller in his 20 February press briefing: “The Taliban are not the only Afghans who have a stake in the future of Afghanistan. We will continue to support giving all Afghans, including, of course, women and girls, a voice in shaping their country’s future.”

Miller’s statement drew a strong reaction from IEA Spokesman Zabiullah Mujahed, “Washington has already tasted the results of [its] intervention in Afghanistan and has seen the consequence over the past 20 years,” he told Afghanistan’s state broadcaster, RTA, as quoted by Ava Press, adding that “America should learn from the past and not repeat its mistakes…. Whether you like it or not, the Islamic Emirate represents Afghanistan and its people.”

Nevertheless, and despite the IEA’s opposition to their participation, civil society representatives were, for the most part, upbeat about the impact of their participation at the meeting. In various media interviews and online briefing sessions, they said their presence signalled the resolve of Afghanistan’s interlocutors to engage with a broad base of Afghan stakeholders and presented an apt opportunity for them to raise the voices of the Afghan people to international fora. Two representatives, Shah Gul Rezai and Metra Mehran, released their statements publicly (see Rezai’s here and Mehran’s here). Mehran said the Independent Assessment Report was “unduly conciliatory towards the regime” and urged participants not to “compromise our rights for your regional and international political rivalries.” Echoing the frustrations she and other Afghan women felt, she said:

Our trust in all of you has been severely tested; as women and people of Afghanistan, it feels like we are fighting on multiple fronts – against the Taliban and also to convince the international community to not turn away or ignore our plight. We are being eased [sic] from our own society as the whole world watches. During these talks, and as you go forward, you have the opportunity to ensure that this erasure isn’t legitimized, downplayed or perpetuated. I urge you to heed the calls of women and ensure that the outcome of these talks is grounded in, and center, women’s rights and agency.

Disagreements at Doha hamper consensus

Despite the Emirate’s snub and disagreements among the participants, Guterres put on a brave face during the press conference held after the two-day meeting, on 19 February. There was consensus among the participants, he said, concerning the assessment report’s “programmatic proposals” as well as the “end game” (see UN Web TV and a transcript of the press conference). The UN Secretary-General defined this unanimous vision as:

Afghanistan in peace with itself and peace with its neighbours. Able to assume the commitments and international obligations of a sovereign state and at the same time, doing so in relation to the international community, the other countries, its neighbors, and in relation to the rights of its own population. At that same time an, Afghanistan fully integrated in all the mechanisms, political and economic, of the international community. This is the objective, the endgame.

Guterres, however, stressed that the group of envoys had been deadlocked on an “essential set of questions,” leaving Afghanistan with a government that is not recognised internationally, on the one hand, and with a perception among special envoys that inclusiveness in government had not improved, the situation of women and girls, and human rights in general, had deteriorated, and “problems of the fight against terrorism are not entirely solved.” He described “a situation of the chicken and the egg,” with the Taleban calling for recognition and asserting that the issues raised by the international community are “not their business” and “the international community thinking that there is no progress in relation to its main concerns.”

Guterres said that all the participants had agreed that meetings of special envoys and special representatives on Afghanistan should continue in the future, but not without the Emirate’s participation. He also said the UN would appoint a special envoy, but only after “a serious process of consultations” to pave the way for the IEA to agree to the appointment. Finally, a contact group would be established, and while it was up to member states to decide the particulars, Guterres said he had put forward a personal suggestion that this group should be made up of the permanent members of the UNSC, also known as the P-5 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), a group of neighbouring countries (this would include Iran and Pakistan) and a group of “relevant donors.” On the face of it, this composition sounds like a good idea, but it might prove to be a non-starter. While it is not unheard of, one can only imagine the wrangling involved in getting the United States and Iran to agree to sit down together at the same table.

To many, these plans may seem like low-hanging fruit, but reaching an accord on the mechanisms for engagement among some 25 nations and international organisations, each with its own priorities – even before the wishes and possible red lines of the IEA are taken into account – will be no small feat.

In AAN’s last report, ahead of Doha II, we wrote about the possibility of an emerging regional block, with a consensus position on Afghanistan, which would place strengthening ties with Kabul at the centre of its agenda. That dynamic appeared to be proven true by events at Doha and there now appear to be three rough groups of countries, each with its own ideas about the best way to engage with the IEA. First is the nascent regional block, which includes China, Russia and Iran, which have increasingly closer ties with Kabul and are seemingly advocating for the IEA and its positions. A second group of countries are taking an isolationist approach, most notably France (another permanent member of the Security Council) and Germany, both of whom are very critical of the Emirate and its human rights record and want to see the IEA deliver on all its obligations. The third group, spearheaded by the US and UK (also permanent members of the SC), favours a more pragmatic approach, which would see member states engage with the Emirate and try to persuade them to take positive action in fulfilling Afghanistan’s international obligations in exchange for more engagement and progress towards Afghanistan’s reintegration into the world community. In this light, there is a vast gap between the varying positions of Afghanistan’s interlocutors, and the impasse could prove a significant hurdle to reaching a consensus. Finally, the importance of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan as an integral part of this complex puzzle cannot be overlooked, for even if there was an unequivocal consensus among all the other countries, it would be hollow if it failed to gain buy-in from the IEA.

Returning to Guterres, there was more of interest at his 19 February press conference. Responding to a question from Al-Jazeera about reports that the reason for the IEA decision not to attend was because of a “lack of proper communication,” he said: “If the reason was lack of communication, I’m very happy because I can then make sure that the next time, there will be perfect communication, and then the problem will not exist.” Guterres downplayed the absence of IEA representatives from the meeting, saying: “It was not damaging because the meeting was very useful, and we absolutely needed to have this discussion,” referring to the recommendations of the Independent Assessment, and expressed hope that discussions with the Emirate will “happen in the near future.” In fact, he confirmed that the UN Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, Rosemary di Carlo, who is widely expected to take over the Afghanistan file at the UN, had met with “a representative of the Taliban in Doha” earlier that day. “So, the contacts are moving on, and they will move on,” Guterres said. “I hope we are not discussing the divorce but we are discussing, as I said, a failure of communication.”

Other reactions to the meeting in Doha – from China, Russia and other Afghans

Not everyone was as positive as Guterres about the outcome of the meeting, with regional countries leading the way in the criticism of the gathering and its failure to engage with the IEA. China’s Special Envoy for Afghanistan, Yue Xiaoyong was quoted in media reports as saying: “It’s a pity that the Doha meeting on Afghanistan once again failed to have a dialogue with the interim Afghan government or the ruling party as China and regional countries have been calling for”(see this Ariana News report).

While neither Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, nor their Special Envoy to Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov made a statement about the Doha meeting, the criticism came from a spokeswoman of the Russian Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova. She said that plans to appoint a special envoy and a small contact group were added to the agenda “without proper elaboration,” adding that any such initiative was “doomed to failure without the support of Kabul and regional states. She went on to defend the Emirate’s refusal to take part in the meeting:

The delegation of the Afghan government refused to participate due to the humiliating conditions associated with the fact that it was allowed only to minor events involving fugitive emissaries of the so-called Afghan civil society (see Turkey’s Anadolu Agency).

Notably, representatives of Afghanistan’s political groups had not been invited to Doha. Several of these groups issued communiques commenting on their absence from the table. For example, former Foreign Minister Salahuddin Rabbani’s party, Jamiat-e Islami, noted “the non-invitation of Afghanistan’s political parties and movements to this meeting as a serious flaw,” but nevertheless welcomed it as a “notable step, which signaled a return of regional and global attention to the situation in Afghanistan (see this post on X). The communique said the only acceptable political system is one based on the vote of the Afghan people and cautioned against “a distortion of the concept of inclusive government to include certain individuals in a political structure with the Taliban at the helm,” which it said amounted to “a trick to legitimize the Taliban.”

The National Resistance Front of Afghanistan, led by Ahmad Massud, also issued a statement that made no reference to the fact that it had not been invited to Doha II. Instead, it applauded “the Secretary-General’s refusal to accept the Taliban’s unreasonable conditions for attending the Doha meeting.” The statement was strongly supportive of UN plans, including the special envoy and called for the person who is appointed to be “an impartial, credible, and unmanipulable envoy of a high international stature, who is fully familiar with the nature of the conflict in Afghanistan” (see this post on X).

Inside Afghanistan, people concerned about the future of their country are following developments closely. Since the publication of the Independent Assessment Report, evening discussion programmes on Afghanistan’s airwaves have dedicated the lion’s share of their news agenda to pundits and political commentators deliberating every development – the assessment report, what has come to pass at the UN, the debate among Afghanistan’s foreign interlocutors and the IEA’s reactions. For example, on 25 February, the evening before the UN Security Council was due to hear about what happened at Doha II, former Afghan diplomat and former advisor to the Republic/Jamiat-e Islami politician Abdullah Abdullah, Omar Samad, and ranking member of Hezb-e Islami – Gulbuddin, Amin Karim, joined ToloNews’ Farakhabar programme to talk about what might be expected at the meeting in New York, a world away from the daily lives of Afghans.

Both men praised UN efforts to support Afghanistan and agreed that a special envoy to act as a coordinator and facilitator was necessary to move the world’s engagement and negotiations with the Emirate forward. Karim cautioned the Emirate[3] against banking on the region’s goodwill, saying that “Iran, China and Russia’s views had diverged from the view of the others. They [Iran, Russia and China] want to increasingly remove the US’s hand from Afghanistan, but they don’t pay for 80 per cent of the aid coming into Afghanistan – the West does that.”

Similarly, Samad said that it was to Afghanistan’s benefit not to become a pawn in the “machinations and rivalries between various blocks, regions or world powers.” It would be best for Afghanistan to keep well away from these rivalries, keep the country’s interests in mind and press forward with engagement.” He also commented on the growing rift in the Security Council – between Russia and China on one side and the US on the other, which he said could have a negative impact on the Emirate’s aspirations for recognition as well as humanitarian aid flows at a time when the Afghan economy was struggling to get back on its feet.

Both men cautioned that the IEA must take a balanced approach that furthers relations with both the region and the West and keeps all international parties onside in order to avoid one faction blocking progress in favour of its own interests. “The region alone cannot solve the problems of Afghanistan, but the problems of Afghanistan cannot be solved without the region,” said Karim. It’s in Afghanistan’s interests to engage with the world, he said, politics is “the art of give and take… You can’t say this is what I’m doing – take it or leave it.”

Talking about the UN special envoy, they agreed that the appointment was necessary and appeared to be a red line in the eyes of Afghanistan’s Western interlocutors. They argued that Afghanistan’s progress toward re-integrating into the world community rested on the appointment and stressed that while the IEA had the right and obligation to negotiate on the mandate and the person, it should not rule out a UN special envoy altogether. This, Karim said, would lead to economic ruin and a deepening humanitarian crisis for a nation that was already enduring significant hardship.

Turning their eyes toward the Security Council meeting, which was due to take place the next day, Samad said, “The UN Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, Rosemary di Carlo, is expected to brief the Security Council on the outcomes of the special envoys meeting and also her meeting with members of the IEA liaison office in Doha.” Three issues will be discussed, he said, the appointment of a UN special envoy (which Samad believed could eventually take on another name and a modified remit), who will be part of the small contact group and the next steps for the special envoys or “large format” group (which is tentatively scheduled for May 2024). He pointed to the possibility of another Security Council resolution on Afghanistan in the coming days – at the latest by 17 March, when UNAMA’s mandate is due to be renewed.

The Security Council meets, again

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC)[4] had a private meeting (these types of meetings are held behind closed doors) on Monday, 26 February 2024, to be briefed on the outcome of consultations conducted at Doha II, as mandated by the Security Council’s Resolution 2721. Ahead of the meeting, the independent website Security Council Report ran a brief that included details on how the Doha gathering had gone and how Sinirlioğlu’s recommendations might be acted upon, especially in the matter of the special envoy.

Spokesperson for the UN Secretary-General Stéphane Dujarric would not be drawn on that issue: “That process is ongoing. My years of experience here have taught me not to pretend that I have a timeline. But I know the issue is being taken very seriously and expeditiously,” he said during his regular press briefing on 26 February.

On the day of the Security Council meeting, acting IEA Deputy Foreign Minister, Sher Muhammad Abbas Stanakzai, reiterated its position on the appointment of a special envoy in an interview with ToloNews, with perhaps the best articulation so far by any Emirate official on the subject:

A UN special envoy is always appointed when there is a crisis or a problem in a country. In Afghanistan, there are no problems. At the same time, UNAMA is active here and there is a UN representative. They are cooperating with us both in political and humanitarian affairs. Therefore, we don’t see a need for another UN envoy, which would create another problem.

In an apparent reference to the participation of civil society representatives at the meeting in Doha, he said:

Sometimes people who have no role in the government, no authority from the government and no legitimacy among the Afghan people are invited to meetings in order to portray the Islamic Emirate as weak and to create controversy (see ToloNews here).”

Photo: United Nations, 27 February 2024

Meanwhile, at the UN headquarters in New York, the President of the Security Council for February 2024, Guyana’s Permanent Representative to the UN Carolyn Rodrigues-Birkett, read out a joint statement (see UN Web TV), on behalf of the Signatories of the Shared Commitments to the Principles of Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) on the situation of women in Afghanistan[5] ahead of the private UNSC meeting. Rodrigues-Birkett stressed the group’s commitment to what she called an inclusive political process and to improving the situation of women and girls in Afghanistan:

It must be underscored that sustainable peace, stability and development in Afghanistan can only be achieved if there is an inclusive political process underpinned by respect for the rule of law and the human rights of all Afghan people a process in which the rights of women and girls are fully–respected and the voices of all Afghans are represented.

We strongly condemn the Taliban’s continued systemic gender discrimination and oppression of women and girls in Afghanistan and demand that the Taliban immediately rescind all policies and decrees that repress women and girls, including restrictions on education at secondary and tertiary levels, women’s right to work, freedom of movement and freedom of expression. Women and girls must have full exercise of their human rights and fundamental freedoms in public, political, economic, cultural and social life.

Meetings behind closed doors fuel speculation

The Security Council meeting on 26 February had no apparent outcome, and the world body did not comment on the proceedings at its conclusion. It was not expected to. But the lack of transparency – the mere fact that the world continues to meet to discuss Afghanistan behind closed doors – is something that many Afghans have long commented on with dismay (see for example, this Hasht-e Sobh report from 2 May 2023 and this 26 February 2024 Voice of America interview with Afghan human rights defender Hoda Khamosh). Once again, Afghan pundits speculated in the media about what might be happening behind closed doors and why the meetings have not yielded any tangible results.

Regular commentator on international affairs in the Afghan media Wali Forouzan told Salam Watandar, for example: “In these meetings, countries want to use Afghanistan as a tool to pressure each other. These countries want to secure their own place in Afghanistan and keep Afghanistan from coming under the influence of their rivals.” Afghan human rights defenders and women’s rights activists, who have repeatedly pinned their hopes on various UN meetings and other diplomatic efforts, only to see them dashed, are starting to lose confidence, as Holda Khamosh told the same outlet: “If these meetings had any positive results,”, “we would by now have seen the opening of schools and universities to girls and would be witnessing Afghan women accessing employment opportunities.”

The Emirate, for its part, was quick to dismiss the gathering as a “failure.” Emirate spokesman Zabiullah Mujahed told ToloNews:

In our opinion, the Security Council meeting did not have any notable results. There was no agreement on the issue of Afghanistan, and secondly, when a meeting fails, the members may rush to highlight very small issues as a pretence [to present them] as the meeting’s outcome.

Even before the February meeting in Doha, many were of the opinion that the emergence of a regional block and of mounting tensions between the US and Russia could prove to be an intractable barrier to reaching a consensus. Andrew Watkins from the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) said this could be especially so, given the growing divide and “the tense geopolitical climate” between the US and Russia and China in the Security Council. In a Q&A piece co-authored with USIP’s Kate Bateman, he compared US support for the appointment of a special envoy with Russian and China’s “lukewarm” position on the issue. He argues these factors may also prove a stumbling block for US attempts to “rally allies and partners around a common position” (read the USIP piece here).

Still, while acknowledging the apparent lack of progress precipitated by the region’s support of the IEA position against the appointment of a UN special envoy, many Afghan commentators caution against dismissing the UN-led process as a failure. For the time being, disagreements among the permanent members of the Security Council, with Russia and China on one side and the US and Face on the other, have led to a standstill: “But this is not the end of the road for UN efforts,” Afghanistan’s former acting Ambassador to Canada, Muhammad Daud Qayumi, said on ToloNews’ Farakhabar programme on 27 February.

Doha II not the end of the road

Afghanistan will certainly figure prominently on the UN and world agendas in the coming weeks and months. The day after the Security Council meeting, US Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken spoke at an Alliance for Afghan Women’s Economic Resilience Summit which was hosted by Boston University. Blinken spoke strongly against the Emirate’s restrictions on Afghan women and girls, particularly in education and employment, and restated international commitments to support them:

Countries from around the world, though, are determined to support Afghan women and girls who want to learn, who want to go to school, who want to pursue their educations, who want to work. Countries like Indonesia and Qatar, which have coordinated international efforts to expand educational opportunity for Afghan women, or the more than 70 countries – more than 70 countries in the Middle East, from Asia, from Europe, from the Americas – who came together in a joint statement at the United Nations calling for, and I quote: the full, the equal, the meaningful participation of women and girls in Afghan society.

Two other key meetings are on the Security Council’s schedule this month. First is the regular quarterly report of the Secretary-General on Afghanistan, which is due to be presented in a meeting in the first week of March, and second is a meeting on the renewal of UNAMA’s mandate, which is set to expire on 17 March. The Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett, has also now presented his latest report to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. It pulled no punches, as was expected (the report, A/HRC/55/80, is listed here and Bennett’s presentation was streamed online).

Two and a half years on from the fall of the Islamic Republic, Afghanistan is still ruled by a government that is not recognised and is still under sanctions. The Independent Assessment Report offered a broad roadmap aimed at moving beyond the impasse caused by international condemnation of the Emirate on the one hand and the Emirate’s determination not to ‘bow’ to outside pressure on what it considers sovereign issues on the other. Appointing a special envoy was intended to be a mechanism to facilitate engagement and discussion. Yet, as the rest of the world continues to wrangle over the appointment of a special envoy, which should, at best, be a procedural matter, the well-being of the Afghan people hangs in the balance.

Edited by Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | 28 special envoys and representatives of multinational organisations were originally said to be participating in the meeting, but the number was later reported as 25, possibly because it excludes representatives from the three multinational organisations. The original list was: Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, Pakistan, Qatar, the Republic of Korea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States and Uzbekistan, in addition to the European Union (EU), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The five Afghan civil society representatives at the Doha meeting were: Lutfullah Najafizada, founder and CEO of US-based broadcaster Amu TV; Metra Mehran, US-based gender equity and human rights activist; Shah Gul Rezai, Norway-based former MP from Ghazni province; Mahbouba Seraj, Afghanistan-based women’s rights defender and recipient of Finland’s International Gender Equality Prize and; Faiz Muhammad Zaland, Assistant Professor at Kabul University. Another two civil society representatives from inside Afghanistan reportedly cancelled their trip to Doha after the IEA declined to participate. Former Deputy Foreign Minister and cousin of the Republic’s first president, Hamid Karzai, Hekmat Karzai, was also in Doha, although it is unclear in what capacity (see his post on X). |

| ↑3 | Karim, who is very close to Hezbi leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, referred to the “Tanzim-e Emarat-e Islami-ye Taleban,” (the Taleban’s Islamic Emirate Movement). His intention, with this unusual choice of name, was unclear: Was he implying that the Emirate was a political party, rather than a government, or trying, implicitly, to downgrade its status? |

| ↑4 | The UN Security Council is currently composed of the following 15 Members: Five permanent members – China, France, Russian Federation, the United Kingdom and United States – and ten non-permanent members that are elected for two-year terms by the General Assembly –Algeria, Ecuador, Guyana, Japan, Malta, Mozambique, Republic of Korea, Sierra Leone, Slovenia, Switzerland (see UNSC website). Japan is the current Penholder for Afghanistan, meaning that it will take the initiative on Security Council actions and drafts documents, particularly resolutions, that it negotiates with the permanent members before sharing the text with elected members (read about the Penholder system here). |

| ↑5 | The signatories of the Shared Commitments to the Principles of Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) are Ecuador, France, Guyana, Japan, Malta, the Republic of Korea, Sierra Leone, Slovenia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign