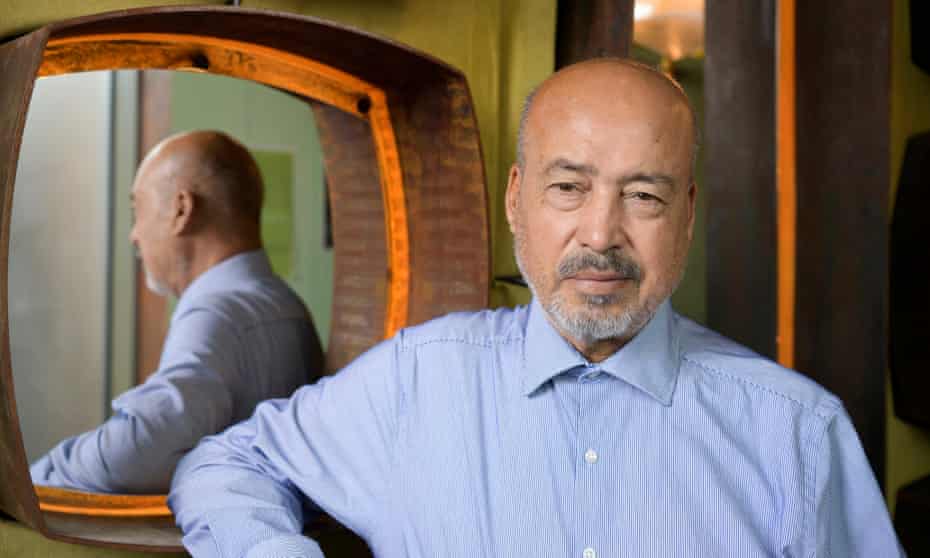

Shah Muhammad Rais, 69, arrived in the UK on 26 September and claimed asylum at the airport. He is waiting for his case to be processed and is currently living alongside other asylum seekers from various conflict zones.

“The UK was the only door open to me to be safe from the Taliban,” he told the Guardian.

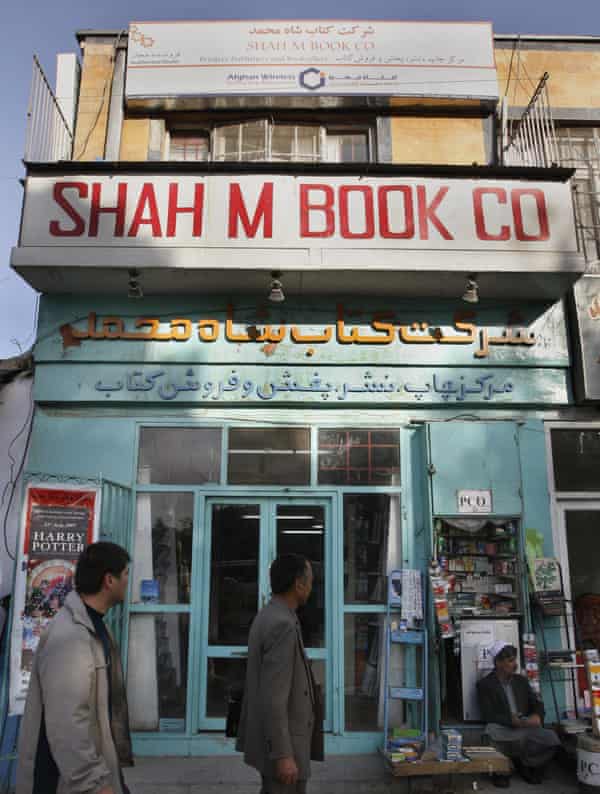

Members of his family, including his nine children and four grandchildren, are scattered across different parts of the world. But his Kabul bookshop is still open following the Taliban takeover, along with an online bookstore. He proudly hands over his business card – Shah M Book Co, printers, publishers, booksellers, Shah Muhammad Rais, managing director.

Independent bookselling times are hard, though and Rais is unsure if the shop, established in 1974 – and that has endured almost five turbulent decades – can withstand the current challenges from the Taliban.

“Very few are buying books now,” he says sadly. One of the consequences of the Taliban takeover has been a mass exodus of intellectuals and others who were part of the book-buying demographic when UK and US forces were in situ in Afghanistan.

“I will keep the bookshop open as long as possible, maybe the Taliban will ban it or destroy it,” he shrugs.

Rais has lived through different rules in Afghanistan and was twice imprisoned during the Soviet era, first in 1979 for a year, and then again a year and a half after his release. He says he experienced torture and mistreatment while he was in jail, including sleep deprivation and being forced to live in freezing conditions.

Åsne Seierstad, a Norwegian journalist, travelled to Afghanistan soon after 9/11 and returned the following spring to write an account of life in the country through an intimate portrait of the lives of one Afghan family – the bookseller Rais, his two wives and his family. The book was based on her account and observations after being invited to move in with the family, with whom she lived for five months.

Rais became famous following the 2002 publication of the book, which topped international sales charts and has been translated into dozens of languages. However, he and members of his family brought a legal action against the author and claimed the book was inaccurate and invasive.

Following a protracted legal battle an appeal court in Norway cleared the author of invading the privacy of the family and concluded the facts of the book were accurate.

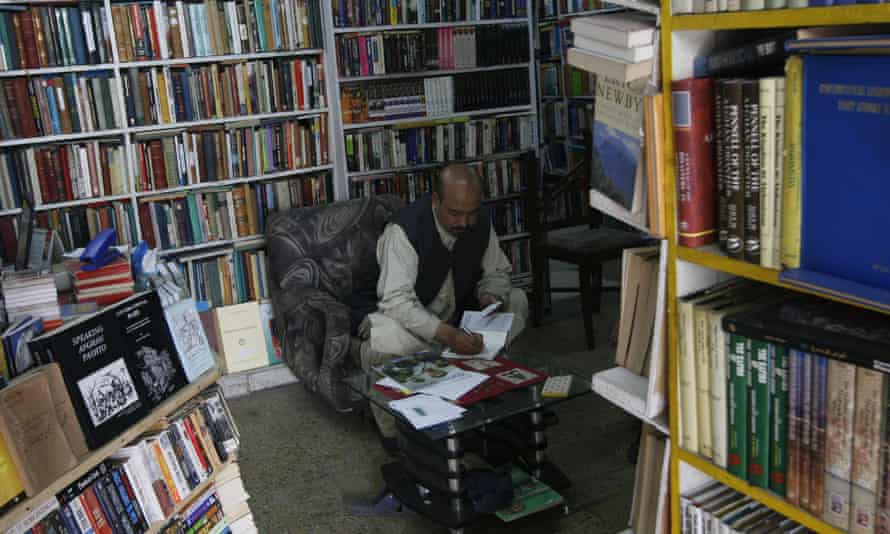

Rais’s bookshop is believed to have the largest collection of books about Afghanistan, expressing a variety of different views of historical events, all under one roof. Along with textbooks for students in areas such as medicine, engineering and languages are many rare books that Rais has found safe hiding places for in case his shop is targeted.

“I have secure places in Iran and Pakistan for some of the books,” he says.

He speaks six languages and says regretfully that he has forgotten a seventh that he was previously able to speak – Russian.

After obtaining a master’s degree in civil engineering at Kabul University, he thought it would not be possible to make a living out of engineering and decided to try to turn his love of books, which he had developed as a teenager, into a business.

Along with his enormous and diverse collection of Afghan books he loves classics including works by Tolstoy, Balzac and Hemingway, and his favourite, the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi. “I loved reading Shakespeare’s Othello in Persian,” he says.

“From 2002 to 2020 I sold over 15,000 copies of European and US literature,” Rais says. He says that his aim has always been to reflect a plurality of views about significant events in history rather than taking one side or another.

“I am on the side of sincerity,” he says. “The Soviets put me in jail for collecting decrees of Mullah Omar and other jihadist newspapers I obtained in Pakistan. I said to the judge: ‘Tomorrow we will need these papers to study Afghan jihad – to understand your enemies.’”

In better times his bookshop was a focal point for intellectuals from a variety of backgrounds to gather, sit on mattresses and listen to international news on a good-quality radio and debate political and philosophical matters of the day.

Now Rais’s future is uncertain as he anxiously awaits the outcome of his asylum claim. And particularly distressing for a lover of books, he now suffers from impaired vision. But his energy and enthusiasm is undimmed.

“If I am granted permission to work in the UK I would love to open an Afghan reading room at the British Library. I’m writing a book on Afghan land, culture and history and would like to open a multicultural, multi-language bookshop here for people from the region – from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran. That is what I’m dreaming of.”

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign