Hasina Safi speaks to Al Jazeera on the global response to the war-torn country’s humanitarian crises.

Belfast, Northern Ireland – The international community’s response to Afghanistan’s ongoing humanitarian crisis is “confused” and requires a wholesale rethink, according to Hasina Safi, the former and last minister for women’s affairs in Afghanistan.

Now a leading women’s rights advocate, Safi told Al Jazeera in a recent interview in Belfast that many in the war-torn country now ruled by the Taliban feel “abandoned” and “forgotten”.

After the Taliban retook power in 2021, Safi’s ministry was replaced by the ministry of “guidance and preaching”.

There has been a failure, Safi said, to follow up a series of pledges made amid the withdrawal of US and UK troops from the territory in late August 2021 with concrete, “practical” responses.

Safi spoke to Al Jazeera at the recent One Young World summit, which brought thousands of young people from more than 190 countries to Belfast.

“Outside Afghanistan, the situation is very confused,” she said.

“The international community do not know what to do. There are conferences, there are events, there are various kinds of programmes. But there is no practical result which can really help the disappointment inside Afghanistan for those who are at risk and deprived,” said Safi.

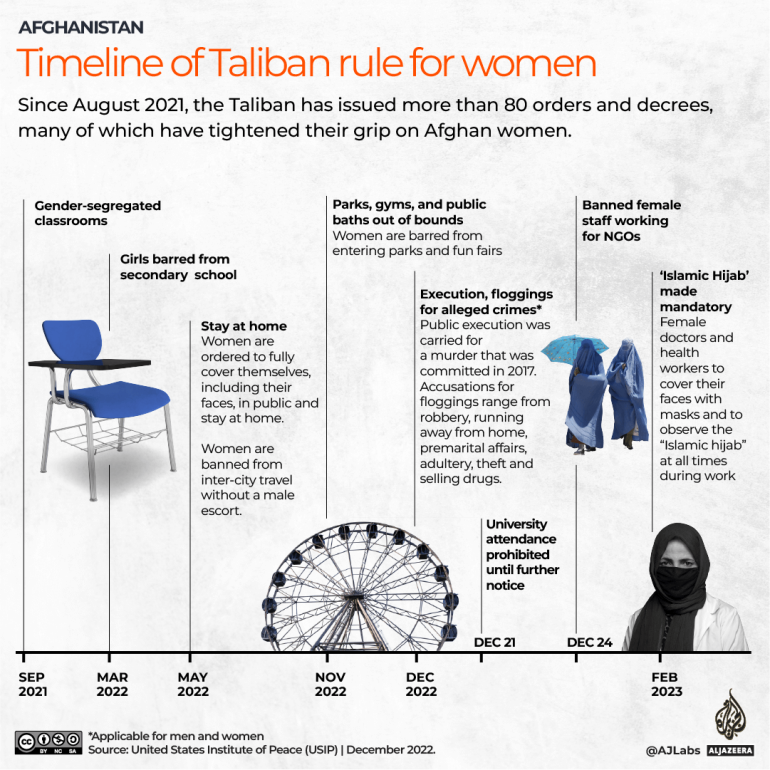

She alleged that a number of decrees issued by the Taliban authorities, which are still not officially recognised by any international government, are considered to be violating international human rights principles.

“The situation is very disappointing. Day by day, instead of introducing mechanisms or coordination in finding ways of supporting people, there are decrees, there are directives – one after the oher,” she said. “Sometimes these are about the clothes they wear, sometimes it’s about make-up, sometimes about their mobility outside.”

Safi also told Al Jazeera that Afghans feel they have been abandoned, as their plight slips down the global news agenda.

“I will not say there is just a ‘sense of abandonment’ – there is abandonment. Period.

“Afghanistan is part of the global human community. It is a country of strategic significance and when the outside world abandons Afghanistan it is abandoning a part of itself.”

She said there is an urgent need to increase aid efforts in Afghanistan, where nearly 50 percent were thought to be living under the poverty line a year before Western forces withdrew from the territory.

“Ensuring higher and higher-secondary education of girls and women is another key priority,” she said.

“And a strategic revisit of the support of the international community to the people of Afghanistan is required. This should be based on the real needs of its people.

“There should be a consolidated report of all the initiatives happening in the last two years – covering [perspectives and experiences] within Afghanistan, the diaspora, the international community – which puts their strategic vision on the table.”

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign