Washington, DC – When Ruqia Balkhi arrived in the United States in September 2023, she was greeted by a federally funded resettlement agency that helped her launch a new life.

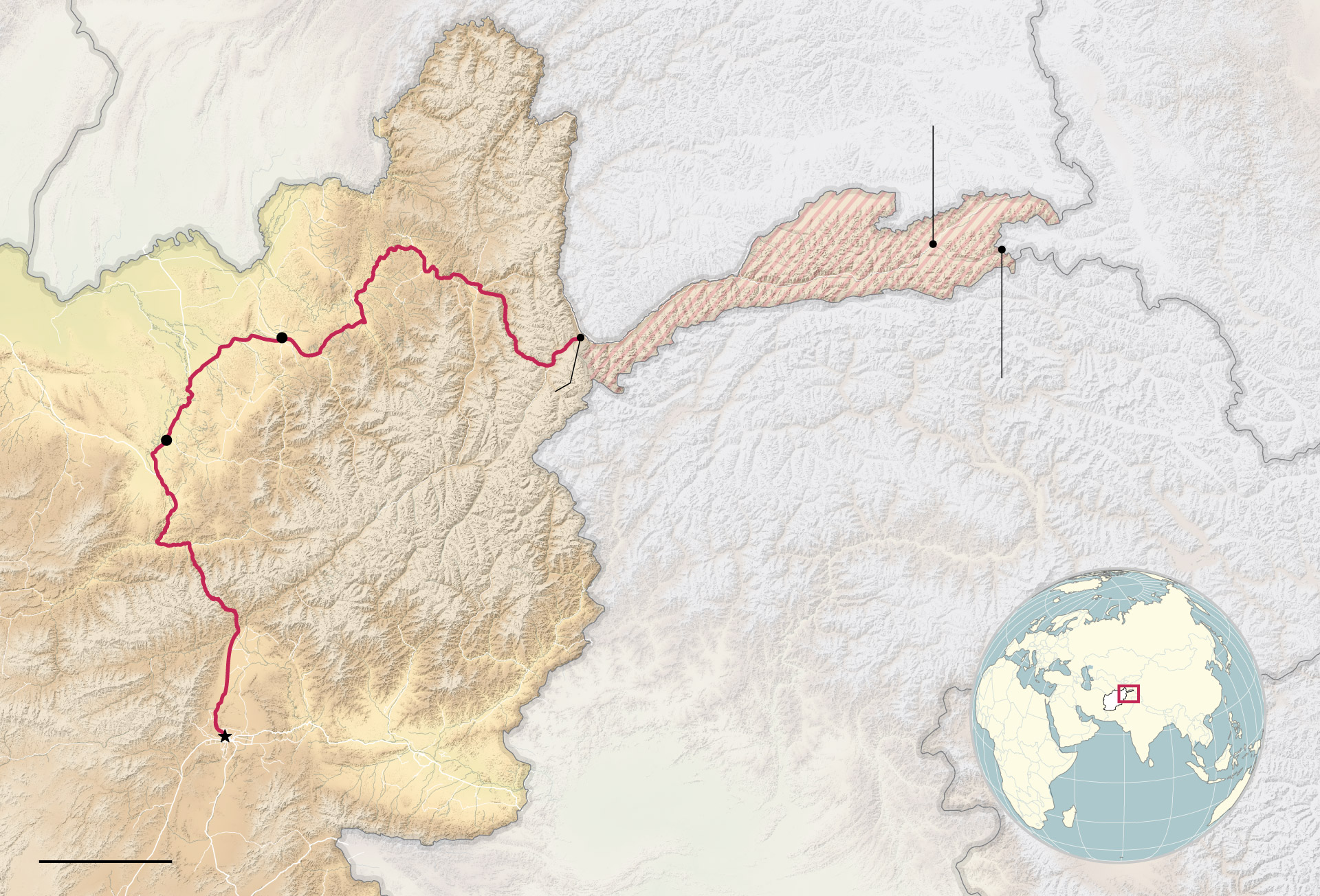

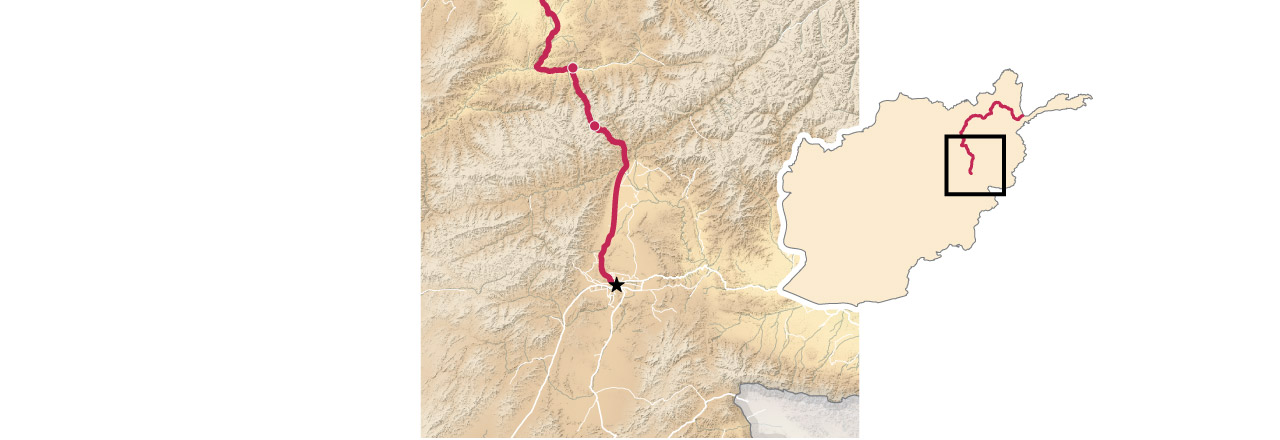

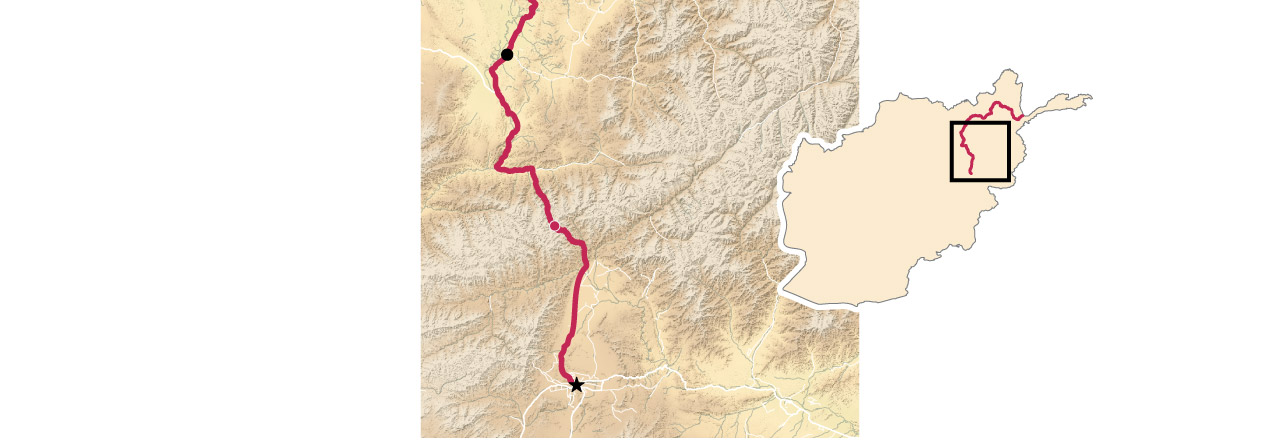

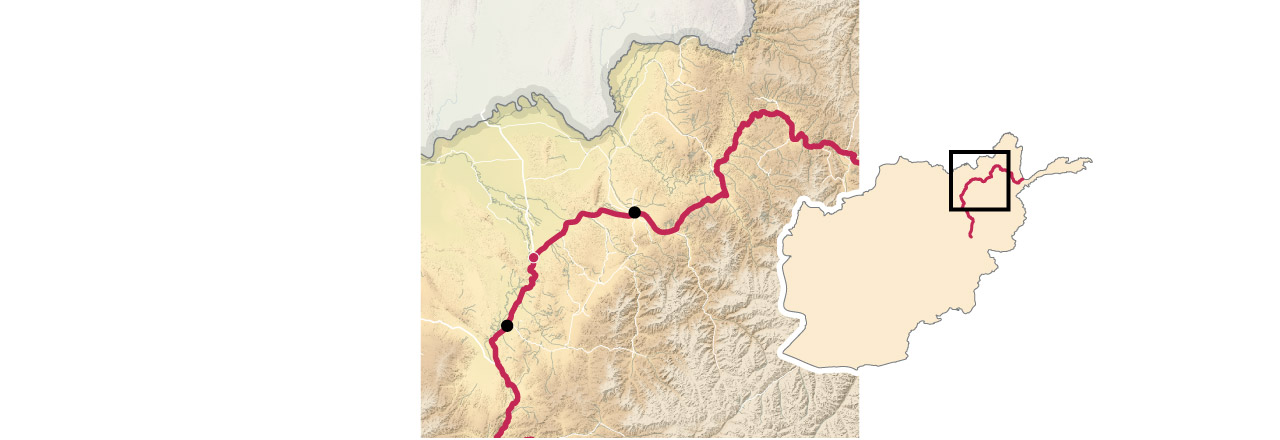

Balkhi, a 55-year-old engineer, was one of the thousands of Afghans who worked alongside the US military during its two-decade-long intervention in her home country.

But after the fall of the US-backed government in 2021, it became unsafe for her to stay in Afghanistan under Taliban leadership.

So she left for the US. During her first 90 days in the country, Balkhi received temporary housing, language lessons, basic goods, mental health support and guidance on enrolling her 15-year-old son in a local school in Virginia.

However, when her husband, Mohammed Aref Mangal, arrived under the same visa programme in January, those services had been abruptly halted. President Donald Trump had just been inaugurated, and the US had tightened restrictions on federal funding and immigration.

“It was completely opposite for my husband,” Balkhi said of the circumstances he faced.

Advocates say her family’s story illustrates how Trump’s broad executive orders might have repercussions even for areas of bipartisan support.

Veteran organisations have largely supported efforts to bring Afghan citizens to safety in the US, particularly if they worked with US forces or the US-backed government.

But in the first days of Trump’s second term, the government paused the US Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), leaving some already approved Afghan applicants stranded abroad.

Another executive order halted foreign aid. That, in turn, has caused interruptions to the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) programme for Afghans who worked with the US military, like Balkhi and her husband.

Balkhi explained that her husband was luckier than most, given that he had a family already established in the US. But she expressed anguish for those entering the country without the same support system she received.

“Without help from the resettlement agency, I don’t think we would have been able to survive,” she told Al Jazeera in Dari, speaking through a translator provided by the Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area.

Some critics see the issue as a test of just how durable Trump’s hardline policies will be when their full impact becomes clear.

“My request from the new government is that they not forget their commitments to Afghan allies and Afghan immigrants,” Balkhi said.

Trump’s campaign promises made no secret of his desire to overhaul the US immigration system, to fend off what he decried as a migrant “invasion”.

But his criticism of the chaotic US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 had sparked hope among those advocating for services for Afghans involved with the US military.

“President Trump campaigned on a bunch of stuff related to Afghanistan, particularly how bad the withdrawal was,” Shawn VanDiver, the founder of #AfghanEvac, an organisation that supports Afghan resettlement.

“So I just don’t believe that he would do that and then not try to help our allies. I’m just hoping this is a mistake.”

In his latest bid for re-election, Trump repeatedly expressed sympathy for those caught up in the August 2021 troop withdrawal, during which a suicide bombing claimed the lives of 13 US service members and 170 Afghans.

Trump also blasted former US President Joe Biden for overseeing the incident, which he called the “Afghanistan calamity”. The day before his inauguration, on January 19, Trump pointedly visited the grave of three soldiers who died during the withdrawal effort.

VanDiver said Trump’s actions from here forward will be critical. If his administration changes course on Afghan resettlement, VanDiver sees that as a hopeful sign.

“But if they don’t change anything, well, then you can be left to conclude that maybe they did mean to do it.”

While Trump’s orders have not directly stopped processing under SIV, they have snarled a pipeline for those seeking relief under the programme, which requires federal funding to operate.

Earlier this month, 10 national organisations that rely on federal support to provide “reception and placement services” received an order to stop work immediately — and incur no further costs.

The State Department’s freeze on foreign aid has also gutted services for those waiting abroad in places like Qatar and Albania, including medical care, food and legal support, VanDiver explained.

Most significantly, Trump’s orders have cut funding for relocation flights run by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Most SIV recipients relied on that transportation reach the US.

“The shutdown of these services isn’t just an inconvenience,” VanDiver said, pointing to the delicate living situations of many Afghans seeking safety. “It could be a death sentence for some of the most vulnerable evacuees.”

Refugee suspension

The SIV programme is not the only one hampered by Trump’s new orders, though.

Refugee resettlement has likewise ground to a halt. Under the previous US administration, Afghans facing persecution from the Taliban could apply for relocation under special refugee categories.

The P1 category was reserved for Afghans referred by the US embassy, while P2 was available for those who worked with the US military, US government-affiliated programmes or nonprofits based in the US. A third category also allowed for family unification, for those with relatives already in the US.

Those pathways have all been closed amid the wider suspension of the US refugee programme.

Kim Staffieri, the executive director of the Association of Wartime Allies, said individuals seeking refuge through those programmes should receive the same urgent attention as SIV recipients.

“There are a lot of people that helped us, who worked for the same goals over there that are very much in danger, but they just don’t qualify for the SIV because it’s got such tight requirements on,” Staffieri said.

She added that she expected Trump’s administration to have given more consideration to Afghan refugees, given the bipartisan support for them.

“We expected some challenges. What we didn’t expect were these broad, sweeping strokes of pausing and suspending necessary programmes,” she told Al Jazeera.

“It feels like either they didn’t have knowledge or they didn’t take time to really think what the downstream effects would be in their entirety.”

Polls have repeatedly shown wide support for resettling Afghans who supported US forces during the war in Afghanistan.

In September 2021, for instance, a poll from NPR and the research firm Ipsos suggested that two-thirds of US respondents backed the relocations, far outpacing support for other groups seeking refuge.

That high level of approval has continued in the years since. An October 2023 poll from the With Honor advocacy group found that 80 percent of respondents signalled continuing support for Afghan resettlement.

US military veterans have been at the forefront of the relocation effort. That demographic, while diverse, typically skews conservative. About 61 percent supported Trump in the 2024 election, according to the Pew Research Center.

Andrew Sullivan, the chief of advocacy and government affairs of No One Left Behind, an SIV advocacy group, described the support as “a matter of national honour and of national security”.

“It is certainly a veterans issue. And so it’s been a bipartisan issue,” said Sullivan.

A veteran of the Afghanistan war himself, Sullivan worked closely alongside an Afghan interpreter when he was an army infantry officer. That interpreter — whom Sullivan identified only by a first name, Ahmadi — has since relocated to the US through the SIV programme.

Sullivan said he was optimistic Trump would eventually create “carve-outs” for Afghans, pointing to the large number of veterans from the Afghanistan conflict in the Republican’s administration.

One of those veterans, former Congressman Mike Waltz, has since become Trump’s White House national security adviser. Waltz previously put pressure on former President Biden to “bring home our Afghan allies”.

Sullivan explained he has repeatedly engaged with Waltz on the issue, and he left feeling hopeful.

“He understands on that personal, visceral level, how much these folks mean to [veterans],” Sullivan said. “So I know he gets it.”

Other advocates, however, are less hopeful. James Powers, a grassroots organiser from Ohio who focuses on veterans issues, pointed to immigration hardliner Stephen Miller’s role in the new administration.

Miller had served in Trump’s first administration when SIV processing had slowed to a trickle.

“It only makes sense that [the programme] would come to a screeching halt as soon as he got back into power to influence the current president,” Powers said.

Advocates also worried that the years of work to grow the current system were at risk.

Just last year, Congress passed a law with bipartisan support that created a special office to coordinate and streamline SIV relocations.

Over the last four years, the Biden administration also expanded the processing of both SIVs and other Afghan refugee categories. Biden’s government issued 33,341 SIVs in fiscal year 2024, about triple the number issued in 2022, the first full fiscal year following the withdrawal.

Afghan refugee admissions also increased from 1,618 in fiscal year 2022 to 14,708 in 2024.

All told, over 200,000 Afghans have been relocated to the US since the withdrawal, including tens of thousands flown on evacuation flights in the immediate aftermath.

“They’ve got to do a better job,” Powers said of the Trump administration. “There are fair experts on both sides of the aisle, on all ideological spectrums, that will tell them there are better ways.”

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign