A series of clashes between local villagers and incoming Pashtun groups in the northern province of Takhar brought the issue of conflict over land back into the spotlight. This is an age-long problem, but the collapse of the Republic shifted local power balances and brought different communities onto the winning side. As a result, many old land claims, conflicts, debts and legal accusations have been revived. The recurring conflict between nomadic Pashtun Kuchis trying to gain access to the summer pastures of Hazarajat and local residents has also resurfaced. This year, however, for the first time since 2001, it is the Taleban who have to manage the myriad competing claims with their potential for conflict.

At the same time, they are seen by a number of communities across Afghanistan as supporting the Kuchis and thus a party to the conflict and not impartial mediators. This report by Fabrizio Foschini (with input from Rama Mirzada) looks into two different cases – the land claims of returning refugees in Takhar, and the Kuchi-Hazara land dispute in the Hazarajat – to assess how the Taleban have been handling land disputes so far, in the context of a radically changed political balance and increasing competition for resources.

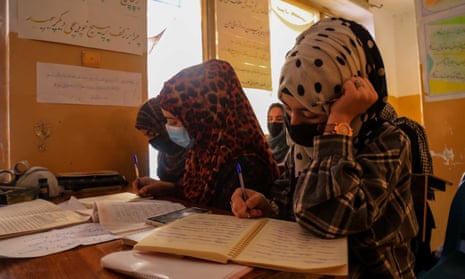

A Kuchi winter camp in Goshta district, Nangrahar. Photo: Fabrizio Foschini, 2012.Layers of migration and displacement on the northeastern border

A Kuchi winter camp in Goshta district, Nangrahar. Photo: Fabrizio Foschini, 2012.Layers of migration and displacement on the northeastern border

In mid-September 2022, clashes erupted in Khwaja Bahauddin district of northeastern Takhar province between local residents and incoming former returning refugees who were trying to settle in the area. The returnees were Pashtun and reportedly many of them of Kuchi, that is nomadic, background. Though they came from Pakistan and some southern and southeastern provinces, where they had lived for the past decades, these Pashtuns claimed to be originally from the area and to possess lands in the district, that they demanded be turned back to them. The confrontation that broke out with the largely Uzbek (and some Tajik) residents left at least three people dead when the opposing sides traded hand grenades.

A land dispute that turns sour is hardly unexpected news in Afghanistan, but in this case – as in many others – the ethnic dimension with its looming political undertones meant it could reverberate far beyond the original dispute. What is relevant in this case is that during the first period of Taleban rule in 1996-2001, Takhar was either controlled or bitterly contested by the forces opposing the Taleban (indeed, Khwaja Bahauddin was the Northern Alliance headquarters where Ahmad Shah Massud was assassinated in 2001). Although the Taleban were able to make inroads among sections of Takhar’s population during the past two decades, the province can certainly not be considered a Taleban stronghold. The National Resistance Front (NRF) is known to operate against the Taleban in the southernmost part of the province and to have supporters in other areas as well. Moreover, the Taleban worry that the Uzbek and Tajik population of the area might be receptive to recruitment campaigns, not only by the NRF, but also ISKP, building on the local presence of other radical Islamist groups such as Jundullah, only loosely aligned with the Taleban (see earlier AAN reporting here and here).

The local Taleban authorities reacted, swiftly and harshly, intervening in favour of the Kuchis. On 6 October, the provincial police chief and deputy governor told the 400 already settled families in the area they would have to vacate their houses and land within three days to make room for the returning refugees (see report here). After the local residents appealed the decision, a prime ministerial committee was appointed to resolve the conflict, at least with regard to the residential houses. The committee recognised the Pashtuns as the original owners, but also ruled that “based on the compassionate decree of Amirul Momineen” and because the Tajiks and Uzbeks had rebuilt the dilapidated houses, they would be given 150 acres (60 hectares) of land nearby. The dispute over the agricultural lands was referred to a special court that is supposed to begin its work soon (read here). The government’s media centre described the decision as a satisfactory solution for all parties, but it is not clear how the newly displaced will organise their housing and survival in the face of the oncoming winter (see here and here).

The confrontation in Khwaja Bahauddin is one among several land disputes that have emerged in Takhar since the Taleban’s return to power, particularly in the northern districts of the province close to the Amu river and the Tajik border, including Dasht-e Qala, Rustaq, Darqad and Yangi Qala. Already in December 2021, The New York Times, in their report about land grabs occurring under the new regime, mentioned the problems experienced by Takhar’s local residents.

Like many of the northern provinces, Takhar presents a multi-layered human landscape, where several waves of Pashtun migrants (naqilin) joined the pre-existing inhabitants during the early and mid-twenty century, encouraged by Afghanistan’s monarchic policies. The low-lying northern border districts, jointly called Mawara-ye Kokcha (the land beyond the Kokcha, after a tributary of the Amu River) became the winter quarters for some groups of mostly Pashtun nomads who in summer moved to the high pastures of Badakhshan. There were also other, non-nomadic, Pashtun settlers in the northeast, whose status and wealth could range from that of political and economic elites, endowed with the best tracts of newly-irrigated land close to provincial centres, to that of groups of land-hungry migrants settled on remote and agriculturally marginal land.

During and after the anti-Soviet jihad, when non-Pashtun groups, locally in a majority, acquired military power and political prominence, the prominent position of some Pashtun communities in the north was challenged. Later, after the fall of the Taleban in 2001, some groups of Pashtuns who were perceived to have supported the Taleban military campaigns against the Northern Alliance were targeted in retaliation. As usual, it was those who already had less – money, connections, protection – that paid the highest price. Accounts of looting, punishment beatings, rape and murder were published by Human Rights Watch.

Between 1998 and 2001, Takhar had indeed been a major battleground between the Taleban and the Northern Alliance. Large groups of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), forced to leave by the scorched earth tactics employed especially by Taleban troops who were on the offensive and largely alien to the province, moved from one side of the frontline to the other, where they were sheltered with scanty international support in refugee camps. This was also the case for one of the main bones of contention of the present dispute: Muhajer Qishlaq or Refugee Village. As the name suggests, this was a settlement where displaced people, unable to go back to their homes in other districts or neighbouring areas, ended up settling. Usually, the land allocated for refugees would be lalmi (non-irrigated), if not simply dasht (in Afghanistan usually meaning ‘desert or steppe’) which belonged to nobody. However, it could well be the case that the government of Burhanuddin Rabbani which still held power in the northeast, in opposition to the Taleban, also distributed lands which had been vacated by previous exoduses of refugees. In general, more Kuchis left Afghanistan for Pakistan in comparison to other communities, particularly during the Soviet occupation, as the ‘total war’ tactics then employed disrupted their pastoralist livelihoods.

In an interview aired on Afghanistan International TV channel on 19 September 2022, Kuchi representatives claimed they had in the past already petitioned the Republic for the restitution of the disputed Takhar lands, but said they had been unable to return to the area, back then, due to the opposition of local armed groups. Takhar was indeed notorious for a chaotic array of militias who vied for power and territorial control from the first years of the Republic. From 2010 onwards, some commanders managed to re-badge their militias as pro-government, irregular armed forces, mostly funded by the state/the United States military and commonly referred to as arbaki. Now that the arbaki, who were for long considered the Taleban’s utmost foes, have been routed, more and more Kuchis are returning and their claims have gained strength.

Many communities involved in long-lasting disputes or competition for local resources, especially when Pashtun and with some past record of support for the Taleban, now feel they are on the winning side and can enjoy the support of the institutions at the local and national level. In Takhar, as in other parts of the country, these groups are set to make the best gains possible off the current situation. This, however, means that other families, villages and even whole communities, who may have only fared slightly better than just survival, are now faced with the sudden loss of one of the very few assets that remain available to Afghans: land to till and to live on. Old disputes originating from the deeds of long-dead kings or strongmen, and from the displacements and dispossessions caused by war, are again coming back to haunt Afghans at this new and demanding junction, threatening to make yet another generation pay for the errors or misfortunes of the past ones.

The Kuchi-Hazara land dispute in 2022

Almost every Afghan province, if not district, has its own, specific type of land dispute, often dating back some decades; each one would require a separate discussion to identify its origin and interpret the potential political fallout. However, the conflict between Kuchi nomads and Hazara villagers in the central highlands of Afghanistan, potentially surpasses all other land disputes for its magnitude, duration and political significance.

Unlike the situation in Takhar, the land dispute in the highlands of Hazarajat did not suddenly emerge after the Taleban returned to power in 2021. In fact, it has been a constant for the last fifteen years (read AAN reporting here and here), despite having been overshadowed by other dramatic issues and largely forgotten during the final years of the Republic.

The conflict centres on the Kuchis’ claim of rights over the summer pastures of Hazarajat, an historical region of central Afghanistan that includes the current provinces of Bamyan and Daikundi, as well as portions of Maidan Wardak, Ghazni, Uruzgan, Ghor, Sar-e Pul, Samangan and Parwan. The Kuchis started to bring their flocks there every summer from their lower-lying winter quarters in the late nineteenth century, after having helped the Afghan emir Abdul Rahman in the war of subjugation of the nearly-independent Hazaras in 1892-93. The grazing rights the Afghan kings granted the Kuchis and the political and economic superiority they enjoyed over the vanquished local Hazara villagers resulted in eighty years of economic and social relations that were structurally unbalanced and unfair. Much of the local agricultural land was purchased by nomads, while their Hazara tenants, often the old proprietors, continued to work it.

The tables were turned after 1979: the Soviet invasion and the subsequent war stopped the nomads’ seasonal transhumance into the highlands, while the birth of the Hazara mujahedin factions sparked the development of a political consciousness among local Hazaras who now had the tools and weapons to defend or regain their lands. Living standards rose because many landlords were no longer extracting rent. After 2001, Hazaras further improved their once poor status in Afghan society, as they took up the opportunities afforded and came to represent an industrious and highly-educated community central to the political and social life of the country. During this time, Hazarajat, albeit remaining a remote and comparatively poor portion of Afghanistan, did benefit from the development brought by its peacefulness.

The only time during the last few decades that the Kuchis were able to enter Hazarajat and reclaim their old rights from a position of force was during the Taleban military occupation of the area in 1999-2001. During the Taleban campaign against Hazarajat, which registered some of the worst episodes of violence against civilians of the Afghan conflict, the Kuchis, coming on the heels of the Taleban troops, demanded twenty years of ‘back rent’ and were reported to have grazed their livestock on wheat fields.

After 2001, the summer pastures of Hazarajat became once more a forbidden fruit for the Kuchis. But although the Kuchis were not able to enter, they did try. From 2007 onwards, yearly confrontations arose on the borders of Hazarajat. Every spring, large groups of Kuchis, both with and without livestock but usually heavily armed, gathered in Maidan Wardak and Ghazni provinces in the districts giving access to Hazarajat from the southeast. This often escalated, with the Kuchis looting and destroying the property of the usually less-armed and outnumbered villagers who tried to confront them, resulting in burnt houses, devastated fields and scores of displaced people. However, they seldom if ever managed to progress further towards the heart of the Hazarajat. Year after year, in the face of a stiffened Hazara resistance, the central government was forced to intervene by deploying security forces and appointing a mediation commission. This commission, with the hefty budget that was allocated to it in good years, usually managed to defuse the situation. The Kuchis would eventually depart, only to come back the following year. This left the impression that, more than a real attempt to reach and reclaim their lost pastures, the yearly confrontation had come to represent something else for the nomads: for the more dispossessed, a platform to call government attention to their plight, and for their opportunistic leaders, an occasion to play the peacemakers and be bribed off by the government (an opportunity in which some Hazara leaders joined as well).

This year, however, for the first time since 2001, the route to the highland pastures lay open and a greater number of Kuchis than in any previous year moved into Hazarajat. Some even reached the Bamyan districts of Panjab and Waras, in the innermost part of Hazarajat, where some of the most prized pastures that the nomads lay claims to are located.

Overall numbers are difficult to estimate, but some local sources interviewed by AAN pointed to great variation depending on the area. In the more remote areas, in the heart of Hazara territory, numbers were relatively low. For instance, only 380 Kuchis were said to have travelled to Panjab district – all armed men and accompanied by the Taleban governor of Bamyan – despite the fact Kuchis claiming ownership of one-third of all arable land in the district. Even fewer, just over a hundred individuals, reached Waras. Numbers seemed much higher in the more easily accessible districts of Maidan Wardak: 1,600 Kuchi families, according to local Hazaras, for the two districts of Behsud 1 and 2 (a Kuchi leader gave the number of more than 300 families, only for Behsud 1).

In the areas they travelled to, the Kuchis’ set of priorities varied but little. First ranked the exaction of payment for the use of the land by the Hazara tenants (hejara). They often claimed payment was due for at least 20 years, sometimes even for the full 43 years since 1979. In some cases during this period, powerful Kuchi businessmen had managed to travel privately to the land they owned inside Hazarajat and settle their accounts with their tenants. Or, more often, the tenants would yearly go to Kabul, Jalalabad or Logar to pay rent to the landlord. But for the past four decades, a great number of Hazara villagers had de facto re-occupied the lands they had previously lost to the nomads, and successfully escaped attempts to extract payment by the formal landlords. Now that those claiming to own the land have returned, sums that were being extracted from the villagers, calculated on what should have been the landlord’s share of multiple harvests, based on the value of a sir (roughly seven kilos)of wheat, easily reached sizeable amounts. For example, a farmer in Waras was reported to have been comparatively lucky, since he only had to pay three years of arrears. This amounted to 52,000 Afs (around 600 USD). Others in Panjab had to compensate for longer periods, paying arrears for sums as high as 280,000 Afs (around 3200 USD) and 500,000 Afs (around 5700 USD).

In many areas, the Kuchis also objected to the houses villagers had built on the land they were now reclaiming, and asked them to either pay for the land they were using or vacate the houses. As few villagers have the capital necessary to buy the plots where they built their homes, many are now trying to resist eviction. In Bamyan province at least, the Kuchis also obtained the restitution of a number of fortified mansions (qala) they had built during the era of their hegemony over Hazarajat.

Some Kuchis have sought to exact the payment of old debts from local villagers. During the decades of the Kuchis’ pre-1979 presence in Hazarajat, many acted as traders, bringing local Hazaras the commodities this remote and underdeveloped region lacked, such as textiles and utensils. According to one of the members of the council that was established to mediate between the Kuchis and the Hazaras in Bamyan (see below), hundreds of old debts have now been brought up, sometimes dating from as far back as 50 years. Once the debts are re-evaluated at the present value of money and with added interest, the amounts can reach staggering heights: the heirs of a deceased farmer in Waras who had once contracted a 70,000 Afs debt were now told to pay 4,500,000 Afs (around 52,000 USD).

The Kuchis have also brought their flocks with them. Hazara interviewees in Behsud assessed the number of livestock brought by each Kuchi family as between 350 and 1,000 animals, while Kuchis there gave an average of 500 per family. The member of the local mediation council estimated that this summer around 10,000 Kuchi sheep and goats had been grazing between Bamyan provincial centre and Yakaolang, , and a similar number in the areas between Yakaolang and Panjab and Waras. Even in the furthermost areas of Bamyan, although they left their families behind, male Kuchis brought their flocks along. Some locals reported that the Kuchis had bought up sheep and goats from cash-stripped villagers in Yakaolang , Saighan and Panjab districts and had thus increased their flocks during their stay there. Local villagers from areas previously visited by Kuchis told AAN the flocks were much larger than previously. This has led many people to believe that the Kuchis, expecting access to abundant and free pastures, had brought along livestock belonging to other residents of Nangrahar, Logar, Khost and even Pakistan, in exchange for money.

If in some remoter districts they stopped for a comparatively short time – the shortest stay was 20 days in Waras – in other areas, Kuchis remained with their flocks for the whole of late spring and summer, leaving only in late September. This meant that in many places through which Kuchis would usually only transit (ie spend some weeks on their way to the higher pastures and some weeks on their way back), they were now settling down for four or five months.

In places like Behsud, where a commission to mediate between the two sides was established at an early stage (more on that later), losses of harvest and crops to the Kuchi livestock received some compensation and the disruption was somehow managed, despite the high numbers of Kuchis who came. Elsewhere, the situation only worsened as the year wore on. According to complaints of local villagers in Nawur district in Ghazni province, Kuchi flocks ate all the available pasture and even grazed crops growing on lalmi (non-irrigated) land (read here). Such situations sometimes escalated and produced the relatively few casualties reported this year.

That so few incidents of armed confrontation took place on one hand points to some of the swift attempts to prevent violence and negotiate compensation on the part of the Taleban authorities, but it also indicates the utter helplessness, de facto and self-perceived, felt by many Hazara villagers.

It is clear that this year, the Kuchis arrived at what had become a yearly confrontation from a position of stark superiority. After the first shows of resistance on the part of Hazaras in the spring, the authorities embarked on a campaign of asymmetrical disarmament. Many Hazaras reported that the Kuchis bore arms freely and even pointed to the distribution of weapons for ‘self-defence’ by local Taleban authorities. In some cases, Kuchis displayed Taleban insignia or uniforms and even appeared on board military vehicles, though it is unclear to what extent this was the result of initiatives by local Taleban commanders or organised by the Kuchis to scare local villagers into submission.

Facing the sudden additional burden of back payments and the threat of displacement, on top of yet another year of drought and the economic crash, Hazara villagers have often seen no alternative than to submit quietly. After over a decade of both sides constructing the conflict as a major ethnic (Hazara versus Pashtun), cultural (sedentary and progressive versus nomadic and conservative), religious (Shia versus Sunni) and political (pro-government versus pro-insurgent) confrontation, local Hazara villagers feel powerless to oppose the claims of the Kuchis, who appear to have full government support, for fear of creating more trouble for themselves.

An early example of what was felt to be retaliation against Hazaras, as the ‘losing side’ by the Taleban was the forcible eviction of thousands of Hazara villagers in Gizab district, shortly after the Taleban takeover in autumn 2021, carried out to satisfy the claim of local Taleban supporters (read here). The eviction, which was later partially repealed, created a generalised feeling of the ‘tables having turned’ in areas which had not been supportive of the Taleban during the insurgency and that considered the Taleban’s conquest of the state as a disaster and political defeat.

It is not always easy to distinguish between actual Taleban policies vis-à-vis land conflicts and the ways in which individuals or groups try to opportunistically use their connection to the winning side to reap easy benefits, disadvantage old rivals and strengthen their own position. Even so, the de facto actions of Taleban officials and supporters, while being a confusing mix of intervention, indifference and impunity have overall, created the widespread perception among Hazaras that the authorities largely identify with the Kuchi side and have backed them.

At the same time, the Taleban, in its role as the central government, has also sought to manage the Hazara-Kuchi conflict.

The Taleban management of the Kuchi-Hazara conflict

After the early, widely-publicised displacement in Gizab, parts of the Taleban movement seemed wary to risk a repeat of the widespread condemnation stemming from brazen abuses perpetrated by their supporters against rival communities. So, early steps were taken by the Emirate to reduce the likelihood of new outbursts of the Kuchi-Hazara conflict and show that they were in control of the situation. This also fits their self-image as a movement able to manage and resolve conflicts and act decisively.

In spring 2022, the Emirate’s leadership established a number of local commissions to mediate between the Kuchis and the Hazara villagers. The existence and effective activity of these commissions, also called councils, is sometimes difficult to assess. However, AAN has been talking to members of commissions in two areas relevant to the Kuchi-Hazara conflict: Bamyan province and the two Behsud districts of Maidan Wardak.

The impetus for the creation of the commissions was the visit of a high-profile Taleban delegation to Behsud in response to the first armed incidents between local Hazaras and incoming Kuchis in spring 2022. The delegation from Kabul, which included Minister of Border and Tribal Affairs Mullah Nurullah Nuri, Deputy Minister of Interior Mawlawi Nur Jala and Deputy Minister of Agriculture Mawlawi Fazl Bari Fazl, held a meeting with Hazaras, Kuchis and local officials, after which a joint commission was formed to work on resolving disputes. According to a Kuchi leader selected as a member of the commission for Behsud 2 district, the delegation also urged the governors of Maidan Wardak and Bamyan to establish security units in these districts to secure the area and prevent conflicts.

The first commission for the two Behsud districts of Wardak was made up of twenty members, ten for each of the two districts, five Hazaras from the area and five Kuchis, mostly coming from Khost for Behsud 1 and from Nangrahar for Behsud 2. Sayed Hashim Jawadi Balkhabi, one of Afghanistan’s few Hazara Taleban, was appointed head of the Behsud commission. According to several Hazaras interviewed by AAN, the Wardak commission was effectively controlled by the Taleban provincial and district authorities and Balkhabi’s appointment was largely a symbolic goodwill gesture towards the Hazaras. In Bamyan, the commission comprised twelve members, six Kuchis and six Hazaras, headed by a Pashtun chief commissioner.

Additional local commissions of six members, all Hazaras, were created in Panjab and Waras. Local Hazara residents claimed that, although the members were selected by the provincial and district Taleban governors – either because they were local allies or relatively weak – both commissions were shunned by the Kuchis as they included no fellow Pashtuns. Most of the cases in these two districts were referred to the central commission in Bamyan.

Although the members did not receive any regular salary, at least the commission in Bamyan received 10,000 Afs (around 115 USD) from both sides for each case that it could resolve. When commissions failed to settle cases, these were referred to the courts.

The commissioners said the commissions stepped in whenever two parties who could not reach a consensus referred the matter to them. So far, they have worked mostly on establishing the amounts of arrears villagers have to pay to Kuchis for land use, or the compensation (in money or animals) Kuchis have to pay after their flocks had grazed on villagers’ crops. The commission in Maidan Wardak had also played a more political role in defusing tensions when it asked the large number of Kuchis who had arrived in the province not to move into Bamyan until the situation there was more favourable, though its success in having this request complied with is likely down to the Taleban authorities in Maidan Wardak, rather than the commission itself.

Altogether, both in Maidan Wardak and Bamyan, Hazaras deemed the commissions powerless compared to the local Taleban authorities who were themselves often linked to the Kuchis. Hazara interviewees also did not consider the ethnic balance in the commissions a guarantee of impartiality; occasional accusations were made against Hazara commissioners for allegedly acting on behalf of the Kuchis and the Taleban authorities for opportunistic reasons.

Kuchi commissioners on the contrary deemed the work of the commissions useful to prevent conflict and help reclaim the rights they had lost. Speaking to AAN, they however complained about the commissions’ inability or unwillingness to deal with the land titles they had brought, and the lack of a decision on their claims to the exclusive use of wide pasture areas, based not on property titles, but on the farman (decrees) of the Afghan kings.

They said they had been told to wait until next year to be given full possession of the lands for which they claim to hold titles, while a decision on whether to uphold the royal decrees regarding pastures would need to be the subject of a centralised decision by the Emirate. They also said they had been told that if the decision went against them, other alternative places would be allocated to them. This suggested that the government delegation and provincial Taleban governors had briefed the commissions on the need for a comprehensive approach to the issue of land occupation and restitution. This was indeed confirmed, when, on 21 October, the Taleban announced a decree from the supreme leader regarding the occupation and restitution of state lands, which would arguably include the Hazarajat pastures. The decree included a nine-provision action plan and the establishment of a commission to “prevent land grabbing and transfer usurped lands,” as well as a special court to deal with the cases. The commission is composed of various relevant ministers, with the notable exception of the Minister of Border and Tribal Affairs, traditionally the one state institution to engage with the Kuchis the most.

But despite attempts to prevent major confrontations and to win time, at least at the central level, there has also been a clear pattern of abusive and self-interested behaviour in favour of the Kuchis by local Taleban authorities. This is exacerbated by the fact that in many Hazara-inhabited districts, following their military conquest by outsiders and in the absence of dependable local Taleban supporters, the new officials are often from neighbouring Pashtun areas and often have private interests and biases in disputes over local resources. For instance, according to a village elder in Malestan of Ghazni it was not the Kuchis that were now claiming lands or pastures in the district, but rather some Pashtuns from neighbouring Ajrestan district with whom locals had had bitter disputes in the past. He said they were exploiting the new situation, with fellow Ajrestanis holding institutional power in Malestan, to advance ungrounded claims.

A new trend: Old judiciary cases brought up

Another salient trend across the Hazarajat has been the re-opening of sometimes decades-old judicial cases relating to Kuchi claims of human or animal losses in past confrontations with the Hazaras. This was despite the fact that the Taleban’s general amnesty featured prominently in the guidelines given to the Kuchi-Hazara mediation commissions at their inception, with its emphasis on forgiveness of past offences on both sides. Cases that have been reported to AAN by local elders or other villagers include:

- In Jalrez district of Maidan Wardak, three years ago, local Hazaras connected to militia commander Abdul Ghani Alipur burned some tents and vehicles belonging to Kuchis who had come to the district. Under the old government, residents of the Hazara villages involved in the incident had been made to pay 4,500,000 Afs (around 52,000 USD) as compensation and the matter was reportedly closed. However, during the winter of 2021-22, a number of local villagers were arrested after the Kuchis demanded that a further sum be paid for the mistreatment they had suffered. The villagers were held until the whole local community agreed to put together the money to pay the additional fine.

- In Nawur district of Ghazni, two Kuchi shepherds were killed by Hazaras eight years ago in an uninhabited mountain tract, and some 250 of their sheep were stolen. From July 2022 onwards, Taleban authorities have been detaining groups of men from the closest villages to force the communities to pay a blood price. Local elders only recently managed to get the last batch of prisoners released after travelling to Kabul and pleading with the cabinet. They claim the local authorities do not want to refer the case to the courts for investigation, preferring illegal or irregular pressure in order to squeeze the largest possible amount of blood money.

- Also, in Nawur district, a Kuchi woman was killed during an armed confrontation four years ago. This year, the blood price was set at ten million Afs (around 115,000 USD) by the local commission. It was for the entire village to pay. When the villagers failed to pay up, a number of its inhabitants were imprisoned. The Kuchis later added accusations of rape and are now asking for additional compensation.

- A conflict from 1990 between Hazaras from the Malestan district of Ghazni, and Pashtuns from neighbouring Ajrestan district, back then thought to have been settled through negotiation, has been revived and the Hazaras have been asked to pay 62,500,000 Pakistani rupees (around 280,000 USD) for the livestock losses suffered by the Kuchis at the time. By order of the Malestan district governor (who is himself from Ajrestan), every villager who failed to pay would be imprisoned until the full amount was handed over. Kuchis appear only marginally in this case, though one Kuchi, a resident of Kandahar, has separately approached locals asking for compensation for the alleged theft of livestock and cash by Hazaras during the same conflict in 1990. When Hazara villagers referred his case to the conflict resolution commission and the attorney general, the plaintiff resorted to threats and intimidation (threatening to kidnap local Hazaras for ransom, if he lost in court).

- In Shebar district of Bamyan, a Kuchi man was killed 30 years ago. According to a commission member from Bamyan, the case has not yet been finalised, but once settled, the amount of blood money will need to be paid by all households of the village concerned.

- In Khedir district of Daikundi, five Kuchis were killed 40 years ago. Towards the end of September 2022, Taleban authorities imprisoned nearly 40 Hazara elders from various villages in the district and forced local people to pay blood money of nearly one million Afs (around 15,000 USD) (read also here)

In all these cases, the local Taleban authorities’ modus operandi has been to side with the Kuchi/Pashtun party and enforce compliance with their demands by meting out collective punishments to local communities. This practice offers the authorities arguably more than just the prompt payment of fines or blood money: it represents a way to pre-empt or break Hazara resistance and potential openly expressed opposition to the Kuchi claims – and, by extension, Taleban power – by forcing whole communities into submission.

The threat of additional fines and imprisonment if they do not comply with Taleban orders has significantly contributed to a feeling of helplessness among Hazaras. The lack of recourse and leverage was so acute that some community elders advised individuals or families who have serious issues with the nomads to leave, since they would be unable to receive support from the village and instead threatened to endanger the whole community.

At the same time, it seems that all the parties involved are aware of the unpredictability of political power and that the pattern of dominance may not last forever. Some Kuchis are selling the lands they have just reclaimed before another change in fortune might occur. According to local Hazaras in Panjab district, some Kuchis who visited the district this summer, chiefly those who have moved to Pakistan or the Gulf countries and now have the bulk of their economic activities there, are willing to sell the land to the Hazaras sharecroppers who are working the land. The problem is that most Hazaras cannot easily afford to purchase it.

However, not all Kuchis benefit from the current situation. Many continue to share with the highland Hazaras at least one common trait: to be among Afghanistan’s most dispossessed and economically vulnerable communities. In the context of an ever-contracting economy and the climate crisis, and harsher competition for the scanty resources that are left, it is difficult to imagine a solution for the large tracts of land that are claimed by different communities, that will leave all sides satisfied and that meets all the different demands and needs.

Where does this come from, and where might it lead?

Many of these decisions, actions and developments point to the convergence of interests between Kuchis and the Taleban – both among local Taleban authorities and within the higher echelons of the central Taleban government – and what may indeed amount to a deliberate pro-Kuchi strategy by parts of the Emirate. The question now is what the Taleban government has to gain in getting so deeply involved in the notoriously sensitive and disruptive issue of land disputes between Kuchis and sedentary communities, and what the rationale may be behind their generally siding with the Kuchis.

There seem to be at least seven possible motivations:

- Taleban tribal/ethnic solidarity with Kuchi groups vis-à-vis non-Pashtun communities: Ethnic polarisation is no newcomer to the Afghan conflict, and it is clear, despite the movement’s insistence on its all-Afghan character, that the Taleban at the very least does not fully trust non-Pashtun groups and has largely excluded them from the ranks of the government;

- The need, at the local level, to reward supporters and to settle old scores with rivals: Land in Afghanistan has always been a prized resource to be redistributed to allies. Additionally, in past years under the Republic, communities on the losing side of land disputes would often approach the Taleban asking them to intervene on their behalf in exchange for support or recruits. Now, the Taleban might simply be fulfilling promises they made before their victory.

- The need to relieve the pressure from large groups of returning refugee or land-hungry Kuchis on other areas that are more central to the Taleban geography of power and their supporting communities (see for example this instance of Kuchi-Taleban clashes in central Ghazni)

- The excuse offered by land disputes between communities to disarm local residents, especially those belonging to areas and communities deemed unsupportive or potentially rebellious;

- The possible use of disputes to intimidate said communities through the imposition of fines, detention and the massive presence of security forces;

- The gathering of much needed revenue through the consolidation of power over rural communities and the widespread imposition of taxation (on the expansion of Taleban’s taxation, including village-level demands in the Hazarajat, see this recent AAN paper);

- The creation of a buffer of supportive Pashtun communities in the midst of hostile territories to disrupt the operational capacity and logistic networks of armed opposition groups that may emerge or seek to expand their presence.

The last point requires a few additional words. Afghan news outlets critical of the Taleban, have argued that the Taleban’s aim, in both the northeast and in Hazarajat, is to guarantee military control of the areas they did not manage to conquer during their first rule in the 1990s. The re-settling and empowering of Kuchis in these areas would thus be part of that strategy through a continuation of policies by Afghan kings (from Abdul Rahman to Zaher Shah) to engineer the migration of Pashtuns by allocating land.

Though claims that the Taleban Emirate is implementing a fully-fledged project of Pashtunisation of the country, including by bringing in Pashtun settlers from the other side of the Durand Line (that is, Pakistani nationals), might be a little far-fetched, local Taleban leaders have shown themselves interested in exploiting landless Kuchi and other Pashtun returning refugee groups for purposes of political and military control. Whether planned or just facilitated, the replacement of residents through eviction and land distribution could amount to a Taleban tactic to dilute communities deemed untrustworthy or potentially rebellious by interspersing their supporters among them.

Moreover, competition over areas is not only about controlling stretches of land, but also what and who can travel through them. In places such as northern Takhar, the Taleban might be tempted to replicate Abdul Rahman’s project of establishing a buffer of Pashtuns along the country’s northern borders. At that time, the king feared an invasion from the north. Now, the goal would be a more limited one – sealing the border with Tajikistan, which in the 1990s provided the Taleban’s armed opponents with a major logistical lifeline, prompting Ahmad Shah Massud to establish his headquarters in Khwaja Bahauddin.

Additionally, in the context of the Afghan wars, ‘logistics lifelines’ include cross-border smuggling, in particular narcotic substances, to finance the conflict. The Mawara-ye Kokcha of Takhar has been a primary hotspot for such smuggling and all local players naturally seek to maintain access to this source of income, now that the Taleban are in control of all the major official border crossings.

However, although the Taleban might see benefits to the decision to support Kuchis’ and other communities’ claims, there is also a clear cost. Any government behaving in a unilateral and seemingly ideologically-motivated or otherwise partisan manner with regard to land disputes threatens to lose credibility among and alienate groups of its citizens. That is even more so for a movement that has participated in an ethnically-polarised civil war in the past and is currently displaying almost no inclusiveness towards other ethnicities and social groups.

The risks of pushing communities who have so far remained neutral into active opposition, and even alienating former supporters, became clear last summer with the rebellion of Mawlawi Mehdi, one of very few Taleban commanders belonging to the Shia Hazara community, after the Taleban encroached on his control of local resources (read here for AAN background on him). In June 2022, Mawlawi Mehdi denounced what he called the Taleban’s Pashtun monopoly of power and discrimination against Hazaras and started an armed rebellion in his home district of Balkhab in Sar-e Pul province. It took the Taleban thousands of men and weeks of fighting to quell the uprising. In this case, it was a dispute about the revenue from coal mines, but wresting control over land could provoke similar responses.

Mehdi’s was not a lone instance. Growing dissatisfaction over the lack of rewards or positions, the harsh treatment meted out against their communities and the consequent growing Taleban doubts as to their loyalty, has led other non-Pashtun commanders to fall from grace with the Taleban, as well. Their fate has further distanced their own communities from the government, leading again to more suspicions on the Taleban.

To counter this dynamic, some parts of the Taleban are trying to improve their capacity for mediation within local communities, beyond the ad hoc commissions such as those created for the Hazara-Kuchi conflict. However, the Taleban’s scope for patronage in many areas is mostly limited to ideologically-related groups, such as religious networks. The usually marginal province of Takhar, for example, has been among the first provinces to see the formation of a new council of religious leaders. Unlike the mediation commissions, this council will be permanent and have a budget; in the autumn, the movement’s supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada had a meeting Takhar elders and ulama. However, this may not suffice to counter the negative effects arising from ethnic or communal polarisation in the northeast.

The seeds for the re-emergence of armed conflicts are easily sown, particularly if the Taleban do not weigh the long-term consequences of their decisions and actions, and shape their policies about land issues in order to accommodate the local interests of their supporters to the detriment of other communities, or to achieve a purely military dominance over refractory tracts of the country and its population. The same mistake was previously committed by others. Afghanistan’s land disputes always have the potential to blow up into something bigger, with the risk of grievances fuelling ethnic polarisation and wider conflict. In the end, the Taleban should know how central a role land disputes and disgruntlement over their outcomes can play in fuelling communities’ disaffection with the government and fanning possible insurgency. After all, they themselves, for nearly two decades, benefited from such conflicts in their struggle against the Republic and its foreign allies.

Edited by Martine van Bijlert and Kate Clark

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

A Kuchi winter camp in Goshta district, Nangrahar. Photo: Fabrizio Foschini, 2012.Layers of migration and displacement on the northeastern border

A Kuchi winter camp in Goshta district, Nangrahar. Photo: Fabrizio Foschini, 2012.Layers of migration and displacement on the northeastern border Afghan National Army soldiers set out during an operation in the village of Dasht-e Baghwani, in Nangrahar Province’s Surkh Rod District, to clear Taliban fighters from the area. Photo: Andrew Quilty, 2019.

Afghan National Army soldiers set out during an operation in the village of Dasht-e Baghwani, in Nangrahar Province’s Surkh Rod District, to clear Taliban fighters from the area. Photo: Andrew Quilty, 2019.

Afghans queue outside a bank in Kabul. Photo: Hoshang Hashimi/AFP, 31 August 2021.Once a week at 11:30 at night, after dinner and the evening prayer, after the nightly buzz of my siblings playing around has given way to the steady breathing of sleep, my mother watches me with anxious eyes as I leave the house to go the bank.

Afghans queue outside a bank in Kabul. Photo: Hoshang Hashimi/AFP, 31 August 2021.Once a week at 11:30 at night, after dinner and the evening prayer, after the nightly buzz of my siblings playing around has given way to the steady breathing of sleep, my mother watches me with anxious eyes as I leave the house to go the bank.