The Atlantic

October 2023 issue

Joe Biden was determined to get out of Afghanistan—no matter the cost.

August 1

August is the month when oppressive humidity causes the mass evacuation of official Washington. In 2021, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki piled her family into the car for a week at the beach. Secretary of State Antony Blinken headed to the Hamptons to visit his elderly father. Their boss left for the leafy sanctuary of Camp David.

They knew that when they returned, their attention would shift to a date circled at the end of the month. On August 31, the United States would officially complete its withdrawal from Afghanistan, concluding the longest war in American history.

The State Department didn’t expect to solve Afghanistan’s problems by that date. But if everything went well, there was a chance to wheedle the two warring sides into some sort of agreement that would culminate in the nation’s president, Ashraf Ghani, resigning from office, beginning an orderly transfer of power to a governing coalition that included the Taliban. There was even discussion of Blinken flying out, most likely to Doha, Qatar, to preside over the signing of an accord.

It would be an ending, but not the end. Within the State Department there was a strongly held belief: Even after August 31, the embassy in Kabul would remain open. It wouldn’t be as robustly staffed, but some aid programs would continue; visas would still be issued. The United States—at least not the State Department—wasn’t going to abandon the country.

There were plans for catastrophic scenarios, which had been practiced in tabletop simulations, but no one anticipated that they would be needed. Intelligence assessments asserted that the Afghan military would be able to hold off the Taliban for months, though the number of months kept dwindling as the Taliban conquered terrain more quickly than the analysts had predicted. But as August began, the grim future of Afghanistan seemed to exist in the distance, beyond the end of the month, not on America’s watch.

That grim future arrived disastrously ahead of schedule. What follows is an intimate history of that excruciating month of withdrawal, as narrated by its participants, based on dozens of interviews conducted shortly after the fact, when memories were fresh and emotions raw. At times, as I spoke with these participants, I felt as if I was their confessor. Their failings were so apparent that they had a desperate need to explain themselves, but also an impulse to relive moments of drama and pain more intense than any they had experienced in their career.

During those fraught days, foreign policy, so often debated in the abstract, or conducted from the sanitized remove of the Situation Room, became horrifyingly vivid. President Joe Biden and his aides found themselves staring hard at the consequences of their decisions.

Even in the thick of the crisis, as the details of a mass evacuation swallowed them, the members of Biden’s inner circle could see that the legacy of the month would stalk them into the next election—and perhaps into their obituaries. Though it was a moment when their shortcomings were on obvious display, they also believed it evinced resilience and improvisational skill.

And amid the crisis, a crisis that taxed his character and managerial acumen, the president revealed himself. For a man long caricatured as a political weather vane, Biden exhibited determination, even stubbornness, despite furious criticism from the establishment figures whose approval he usually craved. For a man vaunted for his empathy, he could be detached, even icy, when confronted with the prospect of human suffering.

When it came to foreign policy, Joe Biden possessed a swaggering faith in himself. He liked to knock the diplomats and pundits who would pontificate at the Council on Foreign Relations and the Munich Security Conference. He called them risk-averse, beholden to institutions, lazy in their thinking. Listening to these complaints, a friend once posed the obvious question: If you have such negative things to say about these confabs, then why attend so many of them? Biden replied, “If I don’t go, they’re going to get stale as hell.”

From 12 years as the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—and then eight years as the vice president—Biden had acquired a sense that he could scythe through conventional wisdom. He distrusted mandarins, even those he had hired for his staff. They were always muddying things with theories. One aide recalled that he would say, “You foreign-policy guys, you think this is all pretty complicated. But it’s just like family dynamics.” Foreign affairs was sometimes painful, often futile, but really it was emotional intelligence applied to people with names that were difficult to pronounce. Diplomacy, in Biden’s view, was akin to persuading a pain-in-the-ass uncle to stop drinking so much.

One subject seemed to provoke his contrarian side above all others: the war in Afghanistan. His strong opinions were grounded in experience. Soon after the United States invaded, in late 2001, Biden began visiting the country. He traveled with a sleeping bag; he stood in line alongside Marines, wrapped in a towel, waiting for his turn to shower.

On his first trip, in 2002, Biden met with Interior Minister Yunus Qanuni in his Kabul office, a shell of a building. Qanuni, an old mujahideen fighter, told him: We really appreciate that you have come here. But Americans have a long history of making promises and then breaking them. And if that happens again, the Afghan people are going to be disappointed.

Biden was jet-lagged and irritable. Qanuni’s comments set him off: Let me tell you, if you even think of threatening us … Biden’s aides struggled to calm him down.

In Biden’s moral code, ingratitude is a grievous sin. The United States had evicted the Taliban from power; it had sent young men to die in the nation’s mountains; it would give the new government billions in aid. But throughout the long conflict, Afghan officials kept telling him that the U.S. hadn’t done enough.

The frustration stuck with him, and it clarified his thinking. He began to draw unsentimental conclusions about the war. He could see that the Afghan government was a failed enterprise. He could see that a nation-building campaign of this scale was beyond American capacity.

As vice president, Biden also watched as the military pressured Barack Obama into sending thousands of additional troops to salvage a doomed cause. In his 2020 memoir, A Promised Land, Obama recalled that as he agonized over his Afghan policy, Biden pulled him aside and told him, “Listen to me, boss. Maybe I’ve been around this town for too long, but one thing I know is when these generals are trying to box in a new president.” He drew close and whispered, “Don’t let them jam you.”

Biden developed a theory of how he would succeed where Obama had failed. He wasn’t going to let anyone jam him.

In early february 2021, now-President Biden invited his secretary of defense, Lloyd Austin, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Mark Milley, into the Oval Office. He wanted to acknowledge an emotional truth: “I know you have friends you have lost in this war. I know you feel strongly. I know what you’ve put into this.”

Over the years, Biden had traveled to military bases, frequently accompanied by his fellow senator Chuck Hagel. On those trips, Hagel and Biden dipped in and out of a long-running conversation about war. They traded theories on why the United States would remain mired in unwinnable conflicts. One problem was the psychology of defeat. Generals were terrified of being blamed for a loss, living in history as the one who waved the white flag.

It was this dynamic, in part, that kept the United States entangled in Afghanistan. Politicians who hadn’t served in the military could never summon the will to overrule the generals, and the generals could never admit that they were losing. So the war continued indefinitely, a zombie campaign. Biden believed that he could break this cycle, that he could master the psychology of defeat.

Biden wanted to avoid having his generals feel cornered—even as he guided them to his desired outcome. He wanted them to feel heard, to appreciate his good faith. He told Austin and Milley, “Before I make a decision, you’ll have a chance to look me in the eyes.”

The date set out by the Doha Agreement, which the Trump administration had negotiated with the Taliban, was May 1, 2021. If the Taliban adhered to a set of conditions—engaging in political negotiations with the Afghan government, refraining from attacking U.S. troops, and cutting ties with terrorist groups—then the United States would remove its soldiers from the country by that date. Because of the May deadline, Biden’s first major foreign-policy decision—whether or not to honor the Doha Agreement—would also be the one he seemed to care most about. And it would need to be made in a sprint.

In the spring, after weeks of meetings with generals and foreign-policy advisers, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan had the National Security Council generate two documents for the president to read. One outlined the best case for staying in Afghanistan; the other made the best case for leaving.

This reflected Biden’s belief that he faced a binary choice. If he abandoned the Doha Agreement, attacks on U.S. troops would resume. Since the accord had been signed, in February 2020, the Taliban had grown stronger, forging new alliances and sharpening plans. And thanks to the drawdown of troops that had begun under Donald Trump, the United States no longer had a robust-enough force to fight a surging foe.

Biden’s speech contained a hole that few noted at the time. It scarcely mentioned the Afghan people, with not even an expression of best wishes for the nation the U.S. would be leaving behind.

Biden gathered his aides for one last meeting before he formally made his decision. Toward the end of the session, he asked Sullivan, Blinken, and Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines to leave the room. He wanted to talk with Austin and Milley alone.

Instead of revealing his final decision, Biden told them, “This is hard. I want to go to Camp David this weekend and think about it.”

It was always clear where the president would land. Milley knew that his own preferred path for Afghanistan—leaving a small but meaningful contingent of troops in the country—wasn’t shared by the nation he served, or the new commander in chief. Having just survived Trump and a wave of speculation about how the U.S. military might figure in a coup, Milley was eager to demonstrate his fidelity to civilian rule. If Biden wanted to shape the process to get his preferred result, well, that’s how a democracy should work.

On april 14, Biden announced that he would withdraw American forces from Afghanistan. He delivered remarks explaining his decision in the Treaty Room of the White House, the very spot where, in the fall of 2001, George W. Bush had informed the public of the first American strikes against the Taliban.

Biden’s speech contained a hole that few noted at the time. It scarcely mentioned the Afghan people, with not even an expression of best wishes for the nation that the United States would be leaving behind. The Afghans were apparently only incidental to his thinking. (Biden hadn’t spoken with President Ghani until right before the announcement.) Scranton Joe’s deep reserves of compassion were directed at people with whom he felt a connection; his visceral ties were with American soldiers. When he thought about the military’s rank and file, he couldn’t help but project an image of his own late son, Beau. “I’m the first president in 40 years who knows what it means to have a child serving in a war zone,” he said.

Biden also announced a new deadline for the U.S. withdrawal, which would move from May 1 to September 11, the 20th anniversary of the attack that drew the United States into war. The choice of date was polemical. Although he never officially complained about it, Milley didn’t understand the decision. How did it honor the dead to admit defeat in a conflict that had been waged on their behalf? Eventually, the Biden administration pushed the withdrawal deadline forward to August 31, an implicit concession that it had erred.

But the choice of September 11 was telling. Biden took pride in ending an unhappy chapter in American history. Democrats might have once referred to Afghanistan as the “good war,” but it had become a fruitless fight. It had distracted the United States from policies that might preserve the nation’s geostrategic dominance. By leaving Afghanistan, Biden believed he was redirecting the nation’s gaze to the future: “We’ll be much more formidable to our adversaries and competitors over the long term if we fight the battles for the next 20 years, not the last 20.”

August 6–9

in late june, Jake Sullivan began to worry that the Pentagon had pulled American personnel and materiel out of Afghanistan too precipitously. The rapid drawdown had allowed the Taliban to advance and to win a string of victories against the Afghan army that had caught the administration by surprise. Even if Taliban fighters weren’t firing at American troops, they were continuing to battle the Afghan army and take control of the countryside. Now they’d captured a provincial capital in the remote southwest—a victory that was disturbingly effortless.

Sullivan asked one of his top aides, Homeland Security Adviser Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, to convene a meeting for Sunday, August 8, with officials overseeing the withdrawal. Contingency plans contained a switch that could be flipped in an emergency. To avoid a reprise of the fall of Saigon, with desperate hands clinging to the last choppers out of Vietnam, the government made plans for a noncombatant-evacuation operation, or NEO. The U.S. embassy would shut down and relocate to Hamid Karzai International Airport (or HKIA, as everyone called it). Troops, pre-positioned near the Persian Gulf and waiting at Fort Bragg, in North Carolina, would descend on Kabul to protect the airport. Military transport planes would haul American citizens and visa holders out of the country.

By the time Sherwood-Randall had a chance to assemble the meeting, the most pessimistic expectations had been exceeded. The Taliban had captured four more provincial capitals. General Frank McKenzie, the head of U.S. Central Command, filed a commander’s estimate warning that Kabul could be surrounded within about 30 days—a far faster collapse than previously predicted.

McKenzie’s dire warning did strangely little to alter plans. Sherwood-Randall’s group unanimously agreed that it was too soon to declare a NEO. The embassy in Kabul was particularly forceful on this point. The acting ambassador, Ross Wilson, wanted to avoid cultivating a sense of panic in Kabul, which would further collapse the army and the state. Even the CIA seconded this line of thinking.

August 12

at 2 a.m., Sullivan’s phone rang. It was Mark Milley. The military had received reports that the Taliban had entered the city of Ghazni, less than 100 miles from Kabul.

The intelligence community assumed that the Taliban wouldn’t storm Kabul until after the United States left, because the Taliban wanted to avoid a block‑by‑block battle for the city. But the proximity of the Taliban to the embassy and HKIA was terrifying. It necessitated the decisive action that the administration had thus far resisted. Milley wanted Sullivan to initiate a NEO. If the State Department wasn’t going to move quickly, the president needed to order it to. Sullivan assured him that he would push harder, but it would be two more days before the president officially declared a NEO.

With the passage of each hour, Sullivan’s anxieties grew. He called Lloyd Austin and told him, “I think you need to send someone with bars on his arm to Doha to talk to the Taliban so that they understand not to mess with an evacuation.” Austin agreed to dispatch General McKenzie to renew negotiations.

August 13

austin convened a videoconference with the top civilian and military officials in Kabul. He wanted updates from them before he headed to the White House to brief the president.

Ross Wilson, the acting ambassador, told him, “I need 72 hours before I can begin destroying sensitive documents.”

“You have to be done in 72 hours,” Austin replied.

The Taliban were now perched outside Kabul. Delaying the evacuation of the embassy posed a danger that Austin couldn’t abide. Thousands of troops were about to arrive to protect the new makeshift facility that would be set up at the airport. The moment had come to move there.

Abandoning an embassy has its own protocols; they are rituals of panic. The diplomats had a weekend, more or less, to purge the place: to fill its shredders, burn bins, and disintegrator with documents and hard drives. Anything with an American flag on it needed destroying so it couldn’t be used by the enemy for propaganda purposes.

Wisps of smoke would soon begin to blow from the compound—a plume of what had been classified cables and personnel files. Even for those Afghans who didn’t have access to the internet, the narrative would be legible in the sky.

August 14

on saturday night, Antony Blinken placed a call to Ashraf Ghani. He wanted to make sure the Afghan president remained committed to the negotiations in Doha. The Taliban delegation there was still prepared to agree to a unity government, which it might eventually run, allocating cabinet slots to ministers from Ghani’s government. That notion had broad support from the Afghan political elite. Everyone, even Ghani, agreed that he would need to resign as part of a deal. Blinken wanted to ensure that he wouldn’t waver from his commitments and try to hold on to power.

Although Ghani said that he would comply, he began musing aloud about what might happen if the Taliban invaded Kabul prior to August 31. He told Blinken, “I’d rather die than surrender.”

August 15

the next day, the presidential palace released a video of Ghani talking with security officials on the phone. As he sat at his imposing wooden desk, which once belonged to King Amanullah, who had bolted from the palace to avoid an Islamist uprising in 1929, Ghani’s aides hoped to project a sense of calm.

During the early hours, a small number of Taliban fighters eased their way to the gates of the city, and then into the capital itself. The Taliban leadership didn’t want to invade Kabul until after the American departure. But their soldiers had conquered territory without even firing a shot. In their path, Afghan soldiers simply walked away from checkpoints. Taliban units kept drifting in the direction of the presidential palace.

Rumors traveled more quickly than the invaders. A crowd formed outside a bank in central Kabul. Nervous customers jostled in a chaotic rush to empty their accounts. Guards fired into the air to disperse the melee. The sound of gunfire reverberated through the nearby palace, which had largely emptied for lunch. Ghani’s closest advisers pressed him to flee. “If you stay,” one told him, according to The Washington Post, “you’ll be killed.”

From the March 2022 issue: George Packer on America’s betrayal of Afghanistan

This was a fear rooted in history. In 1996, when the Taliban first invaded Kabul, they hanged the tortured body of the former president from a traffic light. Ghani hustled onto one of three Mi‑17 helicopters waiting inside his compound, bound for Uzbekistan. The New York Times Magazine later reported that the helicopters were instructed to fly low to the terrain, to evade detection by the U.S. military. From Uzbekistan, he would fly to the United Arab Emirates and an ignominious exile. Without time to pack, he left in plastic sandals, accompanied by his wife. On the tarmac, aides and guards grappled over the choppers’ last remaining seats.

When the rest of Ghani’s staff returned from lunch, they moved through the palace searching for the president, unaware that he had abandoned them, and their country.

At approximately 1:45 p.m., Ambassador Wilson went to the embassy lobby for the ceremonial lowering of the flag. Emotionally drained and worried about his own safety, he prepared to leave the embassy behind, a monument to his nation’s defeat.

Wilson made his way to the helicopter pad so that he could be taken to his new outpost at the airport, where he was told that a trio of choppers had just left the presidential palace. Wilson knew what that likely meant. By the time he relayed his suspicions to Washington, officials already possessed intelligence that confirmed Wilson’s hunch: Ghani had fled.

Jake Sullivan relayed the news to Biden, who exploded in frustration: Give me a break.

Later that afternoon, General McKenzie arrived at the Ritz-Carlton in Doha. Well before Ghani’s departure from power, the wizened Marine had scheduled a meeting with an old adversary of the United States, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar.

Baradar wasn’t just any Taliban leader. He was a co-founder of the group, with Mullah Mohammed Omar. McKenzie had arrived with the intention of delivering a stern warning. He barely had time to tweak his agenda after learning of Ghani’s exit.

McKenzie unfolded a map of Afghanistan translated into Pashto. A circle had been drawn around the center of Kabul—a radius of about 25 kilometers—and he pointed to it. He referred to this area as the “ring of death.” If the Taliban operated within those 25 kilometers, McKenzie said, “we’re going to assume hostile intent, and we’ll strike hard.”

McKenzie tried to bolster his threat with logic. He said he didn’t want to end up in a firefight with the Taliban, and that would be a lot less likely to happen if they weren’t in the city.

Baradar not only understood; he agreed. Known as a daring military tactician, he was also a pragmatist. He wanted to transform his group’s inhospitable image; he hoped that foreign embassies, even the American one, would remain in Kabul. Baradar didn’t want a Taliban government to become a pariah state, starved of foreign assistance that it badly needed.

But the McKenzie plan had an elemental problem: It was too late. Taliban fighters were already operating within the ring of death. Kabul was on the brink of anarchy. Armed criminal gangs were already starting to roam the streets. Baradar asked the general, “Are you going to take responsibility for the security of Kabul?”

McKenzie replied that his orders were to run an evacuation. Whatever happens to the security situation in Kabul, he told Baradar, don’t mess with the evacuation, or there will be hell to pay. It was an evasive answer. The United States didn’t have the troops or the will to secure Kabul. McKenzie had no choice but to implicitly cede that job to the Taliban.

Baradar walked toward a window. Because he didn’t speak English, he wanted his adviser to confirm his understanding. “Is he saying that he won’t attack us if we go in?” His adviser told him that he had heard correctly.

As the meeting wrapped up, McKenzie realized that the United States would need to be in constant communication with the Taliban. They were about to be rubbing shoulders with each other in a dense city. Misunderstandings were inevitable. Both sides agreed that they would designate a representative in Kabul to talk through the many complexities so that the old enemies could muddle together toward a common purpose.

Soon after McKenzie and Baradar ended their meeting, Al Jazeera carried a live feed from the presidential palace, showing the Taliban as they went from room to room, in awe of the building, seemingly bemused by their own accomplishment.

They gathered in Ghani’s old office, where a book of poems remained on his desk, across from a box of Kleenex. A Talib sat in the president’s Herman Miller chair. His comrades stood behind him in a tableau, cloth draped over the shoulders of their tunics, guns resting in the crooks of their arms, as if posing for an official portrait.

August 16

the u.s. embassy, now relocated to the airport, became a magnet for humanity. The extent of Afghan desperation shocked officials back in Washington. Only amid the panicked exodus did top officials at the State Department realize that hundreds of thousands of Afghans had fled their homes as civil war swept through the countryside—and made their way to the capital.

The runway divided the airport into halves. A northern sector served as a military outpost and, after the relocation of the embassy, a consular office—the last remaining vestiges of the United States and its promise of liberation. A commercial airport stared at these barracks from across the strip of asphalt.

The commercial facility had been abandoned by the Afghans who worked there. The night shift of air-traffic controllers simply never arrived. The U.S. troops whom Austin had ordered to support the evacuation were only just arriving. So the terminal was overwhelmed. Afghans began to spill onto the tarmac itself.

The crowds arrived in waves. The previous day, Afghans had flooded the tarmac late in the day, then left when they realized that no flights would depart that evening. But in the morning, the compound still wasn’t secure, and it refilled.

In the chaos, it wasn’t entirely clear to Ambassador Wilson who controlled the compound. The Taliban began freely roaming the facility, wielding bludgeons, trying to secure the mob. Apparently, they were working alongside soldiers from the old Afghan army. Wilson received worrying reports of tensions between the two forces.

The imperative was to begin landing transport planes with equipment and soldiers. A C‑17, a warehouse with wings, full of supplies to support the arriving troops, managed to touch down. The crew lowered a ramp to unload the contents of the jet’s belly, but the plane was rushed by a surge of civilians. The Americans on board were no less anxious than the Afghans who greeted them. Almost as quickly as the plane’s back ramp lowered, the crew reboarded and resealed the jet’s entrances. They received permission to flee the uncontrolled scene.

But they could not escape the crowd, for whom the jet was a last chance to avoid the Taliban and the suffering to come. As the plane began to taxi, about a dozen Afghans climbed onto one side of the jet. Others sought to stow away in the wheel well that housed its bulging landing gear. To clear the runway of human traffic, Humvees began rushing alongside the plane. Two Apache helicopters flew just above the ground, to give the Afghans a good scare and to blast the civilians from the plane with rotor wash.

Only after the plane had lifted into the air did the crew discover its place in history. When the pilot couldn’t fully retract the landing gear, a member of the crew went to investigate, staring out of a small porthole. Through the window, it was possible to see scattered human remains.

Videos taken from the tarmac instantly went viral. They showed a dentist from Kabul plunging to the ground from the elevating jet. The footage evoked the photo of a man falling to his death from an upper story of the World Trade Center—images of plummeting bodies bracketing an era.

Over the weekend, Biden had received briefings about the chaos in Kabul in a secure conference room at Camp David. Photographs distributed to the press showed him alone, talking to screens, isolated in his contrarian faith in the righteousness of his decision. Despite the fiasco at the airport, he returned to the White House, stood in the East Room, and proclaimed: “If anything, the developments of the past week reinforced that ending U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan now was the right decision. American troops cannot and should not be fighting in a war and dying in a war that Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves.”

August 17

john bass was having a hard time keeping his mind on the task at hand. From 2017 to 2020, he had served as Washington’s ambassador to Afghanistan. During that tour, Bass did his best to immerse himself in the country and meet its people. He’d planted a garden with a group of Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts and hosted roundtables with journalists. When his term as ambassador ended, he left behind friends, colleagues, and hundreds of acquaintances.

Now Bass kept his eyes on his phone, checking for any word from his old Afghan network. He moved through his day dreading what might come next.

The situation was undeniably bizarre: The success of the American operation now depended largely on the cooperation of the Taliban.

Yet he also had a job that required his attention. The State Department had assigned him to train future ambassadors. In a seminar room in suburban Virginia, he did his best to focus on passing along wisdom to these soon‑to‑be emissaries of the United States.

As class was beginning, his phone lit up. Bass saw the number of the State Department Operations Center. He apologized and stepped out to take the call.

“Are you available to talk to Deputy Secretary Sherman?”

The familiar voice of Wendy Sherman, the No. 2 at the department, came on the line. “I have a mission for you. You must take it, and you need to leave today.” Sherman then told him: “I’m calling to ask you to go back to Kabul to lead the evacuation effort.”

Ambassador Wilson was shattered by the experience of the past week and wasn’t “able to function at the level that was necessary” to complete the job on his own. Sherman needed Bass to help manage the exodus.

Bass hadn’t expected the request. In his flummoxed state, he struggled to pose the questions he thought he might later regret not having asked.

“How much time do we have?”

“Probably about two weeks, a little less than two weeks.”

“I’ve been away from this for 18 months or so.”

“Yep, we know, but we think you’re the right person for this.”

Bass returned to class and scooped up his belongings. “With apologies, I’m going to have to take my leave. I’ve just been asked to go back to Kabul and support the evacuations. So I’ve got to say goodbye and wish you all the best, and you’re all going to be great ambassadors.”

Because he wasn’t living in Washington, Bass didn’t have the necessary gear with him. He drove straight to the nearest REI in search of hiking pants and rugged boots. He needed to pick up a laptop from the IT department in Foggy Bottom. Without knowing much more than what was in the news, Bass rushed to board a plane taking him to the worst crisis in the recent history of American foreign policy.

August 19–25

about 30 hours later—3:30 a.m., Kabul time—Bass touched down at HKIA and immediately began touring the compound. At the American headquarters, he ran into the military heads of the operation, whom he had worked with before. They presented Bass with the state of play. The situation was undeniably bizarre: The success of the American operation now depended largely on the cooperation of the Taliban.

The Americans needed the Taliban to help control the crowds that had formed outside the airport—and to implement systems that would allow passport and visa holders to pass through the throngs. But the Taliban were imperfect allies at best. Their checkpoints were run by warriors from the countryside who didn’t know how to deal with the array of documents being waved in their faces. What was an authentic visa? What about families where the father had a U.S. passport but his wife and children didn’t? Every day, a new set of Taliban soldiers seemed to arrive at checkpoints, unaware of the previous day’s directions. Frustrated with the unruliness, the Taliban would sometimes simply stop letting anyone through.

Abdul Ghani Baradar’s delegation in Doha had passed along the name of a Taliban commander in Kabul—Mawlawi Hamdullah Mukhlis. It had fallen to Major General Chris Donahue, the head of the 82nd Airborne Division, out of Fort Bragg, to coordinate with him. On September 11, 2001, Donahue had been an aide to the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Richard Myers, and had been with him on Capitol Hill when the first plane struck the World Trade Center.

Donahue told Pentagon officials that he had to grit his teeth as he dealt with Mukhlis. But the Taliban commander seemed to feel a camaraderie with his fellow soldier. He confided to Donahue his worry that Afghanistan would suffer from brain drain, as the country’s most talented minds evacuated on American airplanes.

In a videoconference with Mark Milley, back at the Pentagon, Donahue recounted Mukhlis’s fears. According to one Defense Department official in the meeting, his description caused Milley to laugh.

“Don’t be going local on me, Donahue,” he said.

“Don’t worry about me, sir,” Donahue responded. “I’m not buying what they are selling.”

After Bass left his meeting with the military men, including Donahue, he toured the gates of the airport, where Afghans had amassed. He was greeted by the smell of feces and urine, by the sound of gunshots and bullhorns blaring instructions in Dari and Pashto. Dust assaulted his eyes and nose. He felt the heat that emanated from human bodies crowded into narrow spaces.

The atmosphere was tense. Marines and consular officers, some of whom had flown into Kabul from other embassies, were trying to pull passport and visa holders from the crowd. But every time they waded into it, they seemed to provoke a furious reaction. To get plucked from the street by the Americans smacked of cosmic unfairness to those left behind. Sometimes the anger swelled beyond control, so the troops shut down entrances to allow frustrations to subside. Bass was staring at despair in its rawest form. As he studied the people surrounding the airport, he wondered if he could ever make any of this a bit less terrible.

Bass cadged a room in barracks belonging to the Turkish army, which had agreed, before the chaos had descended, to operate and protect the airport after the Americans finally departed. His days tended to follow a pattern. They would begin with the Taliban’s grudging assistance. Then, as lunchtime approached, the Talibs would get hot and hungry. Abruptly, they would stop processing evacuees through their checkpoints. Then, just as suddenly, at six or seven, as the sun began to set, they would begin to cooperate again.

Bass was forever hatching fresh schemes to satisfy the Taliban’s fickle requirements. One day, the Taliban would let buses through without question; the next, they would demand to see passenger manifests in advance. Bass’s staff created official-looking placards to place in bus windows. The Taliban waved them through for a short period, then declared the placard system unreliable.

Throughout the day, Bass would stop what he was doing and join videoconferences with Washington. He became a fixture in the Situation Room. Biden would pepper him with ideas for squeezing more evacuees through the gates. The president’s instinct was to throw himself into the intricacies of troubleshooting. Why don’t we have them meet in parking lots? Can’t we leave the airport and pick them up? Bass would kick around Biden’s proposed solutions with colleagues to determine their plausibility, which was usually low. Still, he appreciated Biden applying pressure, making sure that he didn’t overlook the obvious.

At the end of his first day at the airport, Bass went through his email. A State Department spokesperson had announced Bass’s arrival in Kabul. Friends and colleagues had deluged him with requests to save Afghans. Bass began to scrawl the names from his inbox on a whiteboard in his office. By the time he finished, he’d filled the six-foot‑by‑four-foot surface. He knew there was little chance that he could help. The orders from Washington couldn’t have been clearer. The primary objective was to load planes with U.S. citizens, U.S.-visa holders, and passport holders from partner nations, mostly European ones.

In his mind, Bass kept another running list, of Afghans he had come to know personally during his time as ambassador who were beyond his ability to rescue. Their faces and voices were etched in his memory, and he could be sure that, at some point when he wasn’t rushing to fill C‑17s, they would haunt his sleep.

“Someone on the bus is dying.”

Jake Sullivan was unnerved. What to do with such a dire message from a trusted friend? It described a caravan of five blue-and-white buses stuck 100 yards outside the south gate of the airport, one of them carrying a human being struggling for life. If Sullivan forwarded this problem to an aide, would it get resolved in time?

Sullivan sometimes felt as if every member of the American elite was simultaneously asking for his help. When he left secure rooms, he would grab his phone and check his personal email accounts, which overflowed with pleas. This person just had the Taliban threaten them. They will be shot in 15 hours if you don’t get them out. Some of the senders seemed to be trying to shame him into action. If you don’t do something, their death is on your hands.

Throughout late August, the president himself was fielding requests to help stranded Afghans, from friends and members of Congress. Biden became invested in individual cases. Three buses of women at the Kabul Serena Hotel kept running into logistical obstacles. He told Sullivan, “I want to know what happens to them. I want to know when they make it to the airport.” When the president heard these stories, he would become engrossed in solving the practical challenge of getting people to the airport, mapping routes through the city.

From the September 2022 issue: “I smuggled my laptop past the Taliban so I could write this story”

When Wendy Sherman, the deputy secretary of state, went to check in with members of a task force working on the evacuation, she found grizzled diplomats in tears. She estimated that a quarter of the State Department’s personnel had served in Afghanistan. They felt a connection with the country, an emotional entanglement. Fielding an overwhelming volume of emails describing hardship cases, they easily imagined the faces of refugees. They felt the shame and anger that come with the inability to help. To deal with the trauma, the State Department procured therapy dogs that might ease the staff’s pain.

The State Department redirected the attention of its sprawling apparatus to Afghanistan. Embassies in Mexico City and New Delhi became call centers. Staff in those distant capitals assumed the role of caseworkers, assigned to stay in touch with the remaining American citizens in Afghanistan, counseling them through the terrifying weeks.

Sherman dispatched her Afghan-born chief of staff, Mustafa Popal, to HKIA to support embassy workers and serve as an interpreter. All day long, Sherman responded to pleas for help: from foreign governments’ representatives, who joined a daily videoconference she hosted; from members of Congress; from the cellist Yo‑Yo Ma, writing on behalf of musicians. Amid the crush, she felt compelled to go down to the first floor, to spend 15 minutes cuddling the therapy dogs.

The biden administration hadn’t intended to conduct a full-blown humanitarian evacuation of Afghanistan. It had imagined an orderly and efficient exodus that would extend past August 31, as visa holders boarded commercial flights from the country. As those plans collapsed, the president felt the same swirl of emotions as everyone else watching the desperation at the airport. Over the decades, he had thought about Afghanistan using the cold logic of realism—it was a strategic distraction, a project whose costs outweighed the benefits. Despite his many visits, the country had become an abstraction in his mind. But the graphic suffering in Kabul awakened in him a compassion that he’d never evinced in the debates about the withdrawal.

After seeing the abject desperation on the HKIA tarmac, the president had told the Situation Room that he wanted all the planes flying thousands of troops into the airport to leave filled with evacuees. Pilots should pile American citizens and Afghans with visas into those planes. But there was a category of evacuees that he now especially wanted to help, what the government called “Afghans at risk.” These were the newspaper reporters, the schoolteachers, the filmmakers, the lawyers, the members of a girls’ robotics team who didn’t necessarily have paperwork but did have every reason to fear for their well-being in a Taliban-controlled country.

This was a different sort of mission. The State Department hadn’t vetted all of the Afghans at risk. It didn’t know if they were genuinely endangered or simply strivers looking for a better life. It didn’t know if they would have qualified for the visas that the administration said it issued to those who worked with the Americans, or if they were petty criminals. But if they were in the right place at the right time, they were herded up the ramp of C‑17s.

In anticipation of an evacuation, the United States had built housing at Camp As Sayliyah, a U.S. Army base in the suburbs of Doha. It could hold 8,000 people, housing them as the Department of Homeland Security collected their biometric data and began to vet them for immigration. But it quickly became clear that the United States would fly far more than 8,000 Afghans to Qatar.

As the numbers swelled, the United States set up tents at Al Udeid Air Base, a bus ride away from As Sayliyah. Nearly 15,000 Afghans took up residence there, but their quarters were poorly planned. There weren’t nearly enough toilets or showers. Procuring lunch meant standing in line for three or four hours. Single men slept in cots opposite married women, a transgression of Afghan traditions.

The Qataris, determined to use the crisis to burnish their reputation, erected a small city of air-conditioned wedding tents and began to cater meals for the refugees. But the Biden administration knew that the number of evacuees would soon exceed Qatar’s capacity. It needed to erect a network of camps. What it created was something like the hub-and-spoke system used by commercial airlines. Refugees would fly into Al Udeid and then be redirected to bases across the Middle East and Europe, what the administration termed “lily pads.”

In September, just as refugees were beginning to arrive at Dulles International Airport, outside Washington, D.C., four Afghan evacuees caught the measles. All the refugees in the Middle East and Europe now needed vaccinations, which would require 21 days for immunity to take hold. To keep disease from flying into the United States, the State Department called around the world, asking if Afghans could stay on bases for three extra weeks.

In the end, the U.S. government housed more than 60,000 Afghans in facilities that hadn’t existed before the fall of Kabul. It flew 387 sorties from HKIA. At the height of the operation, an aircraft took off every 45 minutes. A terrible failure of planning necessitated a mad scramble—a mad scramble that was an impressive display of creative determination.

Even as the administration pulled off this feat of logistics, it was pilloried for the clumsiness of the withdrawal. The New York Times’ David Sanger had written, “After seven months in which his administration seemed to exude much-needed competence—getting more than 70 percent of the country’s adults vaccinated, engineering surging job growth and making progress toward a bipartisan infrastructure bill—everything about America’s last days in Afghanistan shattered the imagery.”

Biden didn’t have time to voraciously consume the news, but he was well aware of the coverage, and it infuriated him. It did little to change his mind, though. In the caricature version of Joe Biden that had persisted for decades, he was highly sensitive to shifts in opinion, especially when they emerged from columnists at the Post or the Times. The criticism of the withdrawal caused him to justify the chaos as the inevitable consequence of a difficult decision, even though he had never publicly, or privately, predicted it. Through the whole last decade of the Afghan War, he had detested the conventional wisdom of the foreign-policy elites. They were willing to stay forever, no matter the cost. After defying their delusional promises of progress for so long, he wasn’t going to back down now. In fact, everything he’d witnessed from his seat in the Situation Room confirmed his belief that exiting a war without hope was the best and only course.

So much of the commentary felt overheated to him. He said to an aide: Either the press is losing its mind, or I am.

August 26

every intelligence official watching Kabul was obsessed with the possibility of an attack by ISIS-Khorasan, or ISIS‑K, the Afghan offshoot of the Islamic State, which dreamed of a new caliphate in Central Asia. As the Taliban stormed across Afghanistan, they unlocked a prison at Bagram Air Base, freeing hardened ISIS‑K adherents. ISIS‑K had been founded by veterans of the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban who had broken with their groups, on the grounds that they needed to be replaced by an even more militant vanguard. The intelligence community had been sorting through a roaring river of unmistakable warnings about an imminent assault on the airport.

As the national-security team entered the Situation Room for a morning meeting, it consumed an early, sketchy report of an explosion at one of the gates to HKIA, but it was hard to know if there were any U.S. casualties. Everyone wanted to believe that the United States had escaped unscathed, but everyone had too much experience to believe that. General McKenzie appeared via videoconference in the Situation Room with updates that confirmed the room’s suspicions of American deaths. Biden hung his head and quietly absorbed the reports. In the end, the explosion killed 13 U.S. service members and more than 150 Afghan civilians.

August 29–30

the remains of the dead service members were flown to Dover Air Force Base, in Delaware, for a ritual known as the dignified transfer: Flag-draped caskets are marched down the gangway of a transport plane and driven to the base’s mortuary.

So much about the withdrawal had slipped beyond Biden’s control. But grieving was his expertise. If there was one thing that everyone agreed Biden did more adroitly than any other public official, it was comforting survivors. The Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole once called him “the Designated Mourner.”

Accompanied by his wife, Jill; Mark Milley; Antony Blinken; and Lloyd Austin, Biden made his way to a private room where grieving families had gathered. He knew he would be standing face to face with unbridled anger. A father had already turned his back on Austin and was angrily shouting at Milley, who held up his hands in the posture of surrender.

When Biden entered, he shook the hand of Mark Schmitz, who had lost his 20-year-old son, Jared. In his sorrow, Schmitz couldn’t decide whether he wanted to sit in the presence of the president. According to a report in The Washington Post, the night before, he had told a military officer that he didn’t want to speak to the man whose incompetence he blamed for his son’s death. In the morning, he changed his mind.

Schmitz told the Post that he couldn’t help but glare in Biden’s direction. When Biden approached, he held out a photo of Jared. “Don’t you ever forget that name. Don’t you ever forget that face. Don’t you ever forget the names of the other 12. And take some time to learn their stories.”

“I do know their stories,” Biden replied.

After the dignified transfer, the families piled onto a bus. A sister of one of the dead screamed in Biden’s direction: “I hope you burn in hell.”

Of all the moments in August, this was the one that caused the president to second-guess himself. He asked Press Secretary Jen Psaki: Did I do something wrong? Maybe I should have handled that differently.

As Biden left, Milley saw the pain on the president’s face. He told him: “You made a decision that had to be made. War is a brutal, vicious undertaking. We’re moving forward to the next step.”

That afternoon, Biden returned to the Situation Room. There was pressure, from the Hill and talking heads, to push back the August 31 deadline. But everyone in the room was terrified by the intelligence assessments about ISIS‑K. If the U.S. stayed, it would be hard to avoid the arrival of more caskets at Dover.

As Biden discussed the evacuation, he received a note, which he passed to Milley. According to a White House official present in the room, the general read it aloud: “If you want to catch the 5:30 Mass, you have to leave now.” He turned to the president. “My mother always said it’s okay to miss Mass if you’re doing something important. And I would argue that this is important.” He paused, realizing that the president might need a moment after his bruising day. “This is probably also a time when we need prayers.”

Biden gathered himself to leave. As he stood from his chair, he told the group, “I will be praying for all of you.”

On the morning of the 30th, John Bass was cleaning out his office. An alarm sounded, and he rushed for cover. A rocket flew over the airport from the west and a second crashed into the compound, without inflicting damage.

Bass, ever the stoic, turned to a colleague. “Well, that’s about the only thing that hasn’t happened so far.” He was worried that the rockets weren’t a parting gift, but a prelude to an attack.

Earlier that morning, though, Bass had implored Major General Donahue to delay the departure. He’d asked his military colleagues to remain at the outer access points, because there were reports of American citizens still making their way to them.

Donahue was willing to give Bass a few extra hours. And around 3 a.m., 60 more American-passport holders arrived at the airport. Then, as if anticipating a final burst of American generosity toward refugees, the Taliban opened their checkpoints. A flood of Afghans rushed toward the airport. Bass sent consular officers to stand at the perimeter of concertina wire, next to the paratroopers, scanning for passports, visas, any official-looking document.

An officer caught a glimpse of an Afghan woman in her 20s waving a printout showing that she had received permission to enter the U.S. “Wow. You won the lottery twice,” he told her. “You’re the visa-lottery winner and you’ve made it here in time.” She was one of the final evacuees hustled into the airport.

Around 7 a.m., the last remaining State Department officials in Kabul, including Bass, posed for a photo and then walked up the ramp of a C-17. As Bass prepared for takeoff, he thought about two numbers. In total, the United States had evacuated about 124,000 people, which the White House touted as the most successful airlift in history. Bass also thought about the unknown number of Afghans he had failed to get out. He thought about the friends he couldn’t extricate. He thought about the last time he’d flown out of Kabul, 18 months earlier, and how he had harbored a sense of optimism for the country then. A hopefulness that now felt as remote as the Hindu Kush.

In a command center in the Pentagon’s basement, Lloyd Austin and Mark Milley followed events at the airport through a video feed provided by a drone, the footage filtered through the hazy shades of a night-vision lens. They watched in silence as Donahue, the last American soldier on the ground in Afghanistan, boarded the last C-17 to depart HKIA.

Five C‑17s sat on the runway—carrying “chalk,” as the military refers to the cargo of troops. An officer in the command center narrated the procession for them. “Chalk 1 loaded … Chalk 2 taxiing.”

As the planes departed, there was no applause, no hand-shaking. A murmur returned to the room. Austin and Milley watched the great military project of their generation—a war that had cost the lives of comrades, that had taken them away from their families—end without remark. They stood without ceremony and returned to their offices.

Across the potomac river, Biden sat with Jake Sullivan and Antony Blinken, revising a speech he would deliver the next day. One of Sullivan’s aides passed him a note, which he read to the group: “Chalk 1 in the air.” A few minutes later, the aide returned with an update. All of the planes were safely away.

Some critics had clamored for Biden to fire the advisers who had failed to plan for the chaos at HKIA, to make a sacrificial offering in the spirit of self-abasement. But Biden never deflected blame onto staff. In fact, he privately expressed gratitude to them. And with the last plane in the air, he wanted Blinken and Sullivan to join him in the private dining room next to the Oval Office as he called Austin to thank him. The secretary of defense hadn’t agreed with Biden’s withdrawal plan, but he’d implemented it in the spirit of a good soldier.

America’s longest war was now finally and officially over. Each man looked exhausted. Sullivan hadn’t slept for more than two hours a night over the course of the evacuation. Biden aides sensed that he hadn’t rested much better. Nobody needed to mention how the trauma and political scars might never go away, how the month of August had imperiled a presidency. Before returning to the Oval Office, they spent a moment together, lingering in the melancholy.

This article was adapted from Franklin Foer’s book The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future. It appears in the October 2023 print edition with the headline “The Final Days.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Franklin Foer is a staff writer at The Atlantic.

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

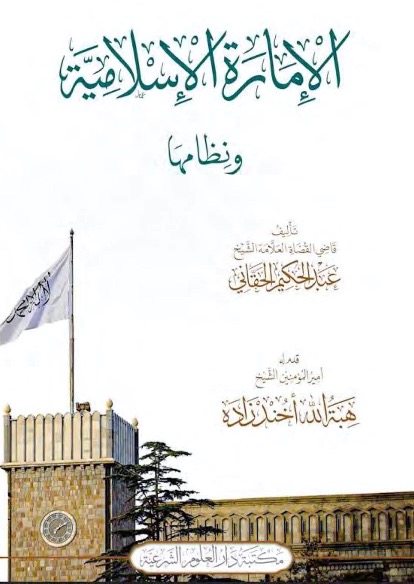

The book cover of ‘Al-Emarat al-Islamiya wa Nidhamuha’ (The Islamic Emirate and its System of Governance) was written by the Islamic Emirate’s Chief Justice, Abdul Hakim Haqqani. Photo: John Butt, X (formerly Twitter), 1 September 2023.You can preview the report online and download it by clicking the link below.

The book cover of ‘Al-Emarat al-Islamiya wa Nidhamuha’ (The Islamic Emirate and its System of Governance) was written by the Islamic Emirate’s Chief Justice, Abdul Hakim Haqqani. Photo: John Butt, X (formerly Twitter), 1 September 2023.You can preview the report online and download it by clicking the link below.