This paper also weaves in information presented in the 43 accountability sessions held over July and August in which ministries and other bodies outlined their achievements for the year in front of journalists and television cameras.[4] The sessions were generally confident and optimistic in tone. Senior officials provided a plethora of statistics – mines surveyed, roads built, licenses and permits issued, rubbish collected, trees planted, trials held, drug addicts treated, books published, training sessions held and so on – presenting an active government working well to serve the people. Some ministers also spoke about the Emirate’s hoped-for direction in the economic sphere, such as in trade, mining and infrastructure projects. However, data on budgets and staffing was patchy and varied from one institution to another, which makes comparisons difficult both between ministries and over time. Those presentations which mentioned changes to staffing, revenue or budgets were the most illuminating.[5]

This report also draws on earlier work by AAN on taxation and spending by the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) and on household economies (see our dossier published earlier this year, bringing these reports together).

Background to the current state of the economy

The collapse of the Islamic Republic and re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate brought both costs and benefits to the Afghan economy. On the one hand, the fact that the Republic disintegrated so precipitously resulted in minimal damage to government infrastructure. The Taleban were able to take over a functioning government apparatus, including public finance, and despite the exodus of many technically able Afghans, they still inherited a better-trained and educated workforce than they left in 2001.

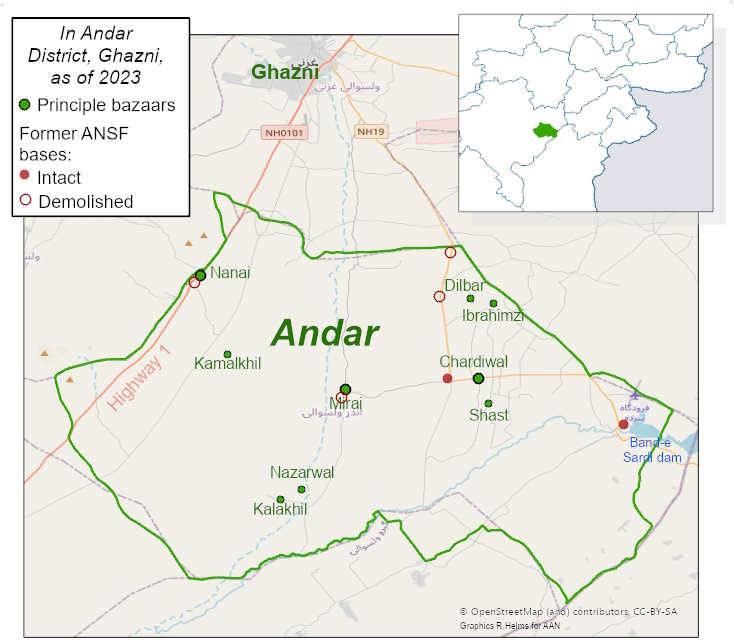

The end to active conflict has also meant that it is now generally safer to travel, farm and indeed live without fear of airstrikes, bombs or fighting.[6] How that looks at its best can be seen in a recent AAN report on Andar district in Ghazni which had been embroiled in the conflict for almost two decades: its economy is now booming thanks to the bazaars re-opening, farmers being able to tend their fields unhindered by fighting, a high level of remittances and the fact that many men in this Taleban-loyal district have found jobs in the government.

However, the Taleban’s capture of power also prompted the economy into free fall, as donor countries abruptly cut off aid, international financial transitions were blocked, the banking system virtually collapsed, and United Nations and United States sanctions hampered trade and remittances. After the UN’s largest appeal for a single country in January 2022, aimed at supporting half of the population assessed to be at “immediate and catastrophic levels of need,” civilian aid did return to similar levels as during the Republic.[7] Even so, the total amount of money coming into Afghanistan remains far smaller than before because spending by the foreign armies and military assistance to the Republic’s armed forces always dwarfed civilian aid. While all three sources of income had declined during the second decade of this century, as countries scaled back their deployments and reduced assistance, even so, in 2019, the Afghan government still received 4.7 billion USD in military support and about 4 billion USD in civilian aid, the latter equally split between on and off-budget support.[8] In 2022, Afghanistan received about 3.5 to 4 billion USD in civilian aid, all off-budget and most of it (70 per cent) humanitarian (all World Bank figures).

During the Republic, the massive amounts of unearned foreign income provided jobs, boosted living standards, supported the afghani and paid for imports, but this ‘bubble economy’ could not survive the sudden removal of the funds in 2021. The magnitude of the foreign income was ultimately damaging to Afghanistan’s economy and to democracy and accountability, as the author explored in an earlier report.[9] However, the money should have tapered off, giving the economy time to adjust. Its sudden disappearance overnight in August 2021 pushed the economy into a catastrophic contraction, with devastating consequences for households, as AAN detailed in a series of reports.

The return of substantial amounts of civilian aid has helped to stabilise the Afghan economy. It has provided not only life-saving assistance but also jobs. The money coming into the economy has supported the domestic currency, the afghani, brought down inflation and stimulated demand. However, donors, who are reluctant to support the Emirate, have mainly funded humanitarian aid. This is meant to be a temporary measure aimed at saving lives until the government or other actors can step in with long-term sustainable plans. It is not intended to act as a long-term solution to address, let alone resolve, a complex humanitarian crisis like Afghanistan’s. It is especially problematic, warned United States Institute for Peace (USIP) William Byrd, when such aid is “a primary source of external financial support propping up the economy.” Moreover, that money and the support it gives to the Afghan economy is shrinking: the UN appeal for aid in 2023 has brought in far less than last year – 1.3 billion USD of reported funding, as compared to 3.9 billion USD in 2022 (see UNOCHA’s Financial Tracking Service).

In winter 2021/22, along with the return of civilian aid to Afghanistan came, not a lifting of US and UN sanctions, as the Emirate has continued to demand, but multiple, wide-ranging waivers to the sanction regimes. Even so, Afghan banks and their customers – business and personal – still do not have the access they used to have to easy international transactions, largely because of the unease felt by foreign corresponding banks in doing business in Afghanistan.

A final major difference in the economy pre and post-August 2021 is the Emirate’s focus on collecting revenue. Less fragmented and less corrupt than the Republic, it has appeared able to channel most revenue into the treasury (rather than much of it going into the pockets of officials and politicians or the insurgency, as previously). Without access to foreign budgetary support, this has become a necessity to keep the government afloat.

All in all, after the traumas of 2021, the economy has stabilised, albeit at a much lower level. This narrative of stabilisation, and even progress, is what the Emirate seeks to portray. Acting deputy Minister of the Economy Ali Latif Nazari, speaking at his ministry’s accountability session in the summer, said that in year one of its rule, the IEA had focussed solely on preventing economic collapse, but in year two, they had worked on boosting the economy: they formulated a development plan, sought to control inflation, collect tax transparently, monitor the ports and custom posts, keep the afghani stable and control fuel and other prices.

Nazari insisted that the Emirate does not consider itself dependent on foreign aid, but rather wants to use and take support from the potential that is inside Afghanistan. At the same time, the Emirate narrative is one of Afghanistan surviving hostile action from the Western states – sanctions, freezing the country’s reserves, banning leaders from travelling and so on. Nazari described the Emirate responding to this with “economic diplomacy,” based on what he called the “self-sufficiency theory.” In an anarchic world that is not unipolar and where national self-interest rules, Afghanistan can thrive: even if it had political tensions with particular countries, he said, they could still be friends economically because of shared economic interests. He spoke about the importance of trade, as did acting Minister of Foreign Affairs Amir Khan Muttaqi when he described Afghanistan’s “economy-oriented politics” which gave Afghanistan “the opportunity to maintain its political status in the region.”

Nazari made clear that economic growth is vital to the Emirate, as it was one of the ways a government gains political legitimacy; economic development – improving people’s livelihoods – reduces the distance between people and government. The Bank would agree, but warns that Afghanistan currently “lacks a self-sustaining indigenous growth engine for recovery.”

How the economy is faring now, two years on from the fall of the Republic and re-establishment of the Emirate, is the subject of the rest of this report. The first section looks at indicators like GDP, prices, the strength of the currency and imports and exports. It is followed by a scrutiny of government revenues and spending and finally an assessment of what all this means for households and businesses.

How the Afghan economy is faring now

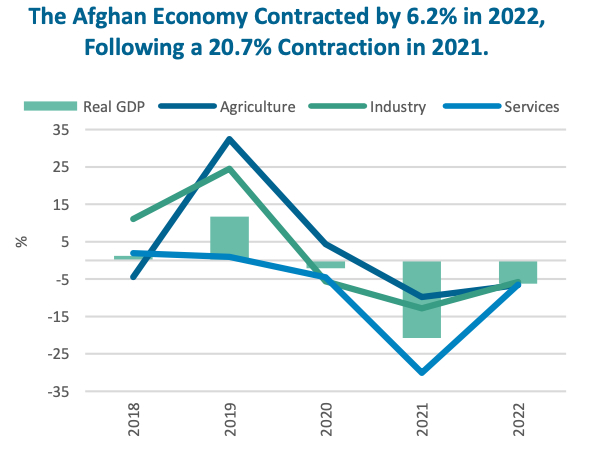

The size of Afghanistan’s economy, measured by its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the total value of all the goods produced and services provided during a year – is smaller than it was before the Taleban takeover. Moreover, the contraction has only slowed, not reversed. GDP, reports the World Bank, contracted by 20.7 per cent in 2021 and the decline has continued into 2022, albeit at a slower rate, by a further 6.2 per cent. The sector contributing most to GDP, services (45 per cent), shrank by 6.5 per cent, but with a considerable variation within that: wholesale trade (-8.9 per cent), health (-5.9 per cent), finance and insurance (-6.6 per cent), real estate (-5.2 per cent), dining and lodging (-4.2 per cent), and telecommunications (-4.7 per cent).

Agriculture, which contributes 36 per cent of GDP, shrank by 6.6 per cent, mainly because of bad weather causing poor harvests and problems for livestock. While the drought continued into 2023, better rain and snow is forecast this winter and spring, so there is hope that Afghanistan’s farmers will fare better in 2024.

Industry suffered an overall 5.7 per cent decline in 2022, again with substantial variation between sectors. There was a 10 per cent fall in manufacturing (including food and beverages and non-food), a 0.8 per cent fall in construction but growth of 4.1 per cent in mining and quarrying. “Dampened demand remains the top business constraint,” said the Bank, “followed by uncertainty about the future and limited banking system functionality.” It highlighted the Emirate’s restrictions on women’s work and education as only adding to the economy’s sluggishness.

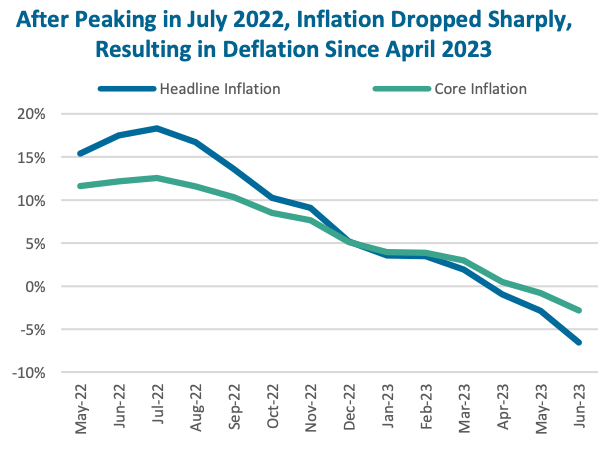

Inflation peaked in July 2022 at 18.3 per cent, but prices are now falling by 9.1 per cent overall. Measured year-on-year since July 2022, the Bank says food is 12.6 per cent and non-food items 5 per cent cheaper. What economists call ‘core inflation’, ie when food and fuel are stripped away, stands at -4.7 per cent. Some of the falling prices, says the Bank, can be explained by better supply of goods and the strengthening of the domestic currency, the afghani, which reduces the cost of imports. However, it warns that falling prices also “likely stem from the economy adjusting to a structurally lower aggregate demand level.” In other words, total demand for all finished goods and services produced by the economy is less than it used to be. Spending by households is down, as is investment by businesses. Anecdotally, it said, this could be attributed to “depleted savings, reduced public spending, and shocks to farmer income from poppy cultivation bans.”

The strength of the currency has been remarkable. This year, up to 24 August 2023, the afghani had appreciated against the US dollar by 7.3 per cent, said the Bank. With 83.1 afghanis buying one dollar, the value was 3.7 per cent higher than on 15 August 2021. In the last few months, however, the afghani has only continued to appreciate. As this report was published, just 72.9 afghanis were needed to buy one dollar. That strengthening is partly due to government actions.

It has banned the use of foreign currency for domestic transactions, including, a money exchanger told AAN, insisting that afghanis not dollars be used to buy houses and land, cash distributions by NGOs and when they buy staple goods, and when government departments purchase materials. Provinces where Pakistani rupees or Iranian riyals are commonly used for everyday purchases have been warned to stop doing so or face the law (see, for example, reporting on 13 September by the national broadcaster, Radio Television Afghanistan). A shopkeeper in Spin Boldak in Kandahar province described to AAN a public meeting in October in which government officials told people to stop using Pakistani rupees “on the order of the Amir,” a message repeated by loudspeaker to the townspeople. The shopkeeper said a mullah had come into his shop and tried to pay for something in rupees. When he refused, the mullah praised him and the shopkeeper realised if he had accepted the rupees, the authorities would have shut his shop, as they have done several other outlets which disobeyed the order.

The government has also banned the export of cash; an example of one high-profile arrest can be seen, on an Emirate website from 6 November 2023). As there has been only limited printing of afghani notes since August 2021, demand for the currency is boosted, and said money changers, the Central Bank is managing the currency well by selling dollars, as needed. Other reasons for the strong currency are external – the dollars brought in by the United Nations to pay for civilian assistance, as well as higher remittances. However, the Bank says that all this still does not fully explain the strength of the currency. Here, the Bank looks to Afghanistan’s recent puzzling import/export figures.

For years, Afghanistan has run a deep trade deficit, funded until 2021 by money coming into the country in the form of spending by foreign armies, military support and civilian aid. In 2020, for example, Afghanistan was importing goods at a value 7.6 times greater than the value of its exports. The precipitous contraction of the economy in 2021 shrank the demand for imported goods, and at the same time Afghanistan’s exports grew. In 2022, Afghanistan imported goods valued at 3.3 times more than the value of its exports.

Exports, those legally exported rather than smuggled out, have benefited from the change of government. 2022 was a record year, said the Bank: Afghanistan exported 1.9 billion USD worth of goods, far higher than the five-year-average, 2016-21, which was just 0.8 billion USD. There is strong foreign demand for certain Afghan goods, such as coal, precious gems, gold and other minerals, fresh and dried fruit and other agricultural produce. Additionally, in 2022, demands for Afghan exports was driven by Pakistani demand for Afghan coal, which is cheap by global standards, and food, following the devastating floods in that country. However, even more important perhaps, as David Mansfield and Alcis mapped, the Emirate, unlike the Republic, pursued stronger border controls, adopted and rigorously enforced Republic-era regulatory frameworks and border management systems and closed smuggling routes.

However, exports are now weakening. The Bank reports that while, overall, in the first seven months of 2023, exports increased by three per cent, since February, they have been falling, with coal exports – down by 12 per cent – especially hard hit.[10] Food comprises the largest type of export, with Pakistan and India as the main customers. With food exports to Pakistan declining in 2023, the Bank said India has become the biggest customer. It also says that “new (albeit small) markets are opening for Afghanistan’s food exports, including the United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Iran, and Iraq.”

Remarkably, however, given the contraction to the economy and reduced aggregate demand, imports have grown. In 2022, they amounted to US$6.3 billion and, in the first seven months of 2023, had already reached US$4.4 billion. That figure, which excludes humanitarian imports, represents a growth of 32 per cent, year-on-year. How can that be possible, given the shrinking economy and Afghans’ much reduced spending power? Increased remittances cover the cost of some of those imports – the estimated 1-1.2 billion USD Afghans abroad sent home in the first seven months of 2023 (a doubling in the amount of money sent compared to 2019). Some could be covered by the regular shipments of cash coming in via the UN to pay for humanitarian aid and support to basic services (1.8 billion USD in 2022 and around 1.12 billion USD in 2023). However, the World Bank calculates this would still leave a projected and unexplained gap of 1 billion USD for January-July 2023.

Moreover, despite all the economic problems, the afghani has been steadily appreciating against major trading currencies since the start of 2023. “Official data and economic theory can’t offer a clear explanation” for how this could happen, the Bank observes drily. It also stresses that the “foreign exchange market seems in balance, as there is no evidence of a parallel exchange market.” The answer to this improbable negative correlation between a contracting GDP, increasing imports and a strengthening currency lies, it says, in an “inflow of foreign currency not shown in any official record.” In other words, there is an informal income stream covering the trade deficit and supporting the afghani.

The nature of that income stream becomes clearer when the types of imports are detailed: high-end consumption goods and industrial raw materials, including prepared food, vehicles, spare parts, stone, glassware, chemicals and iron and steel. Imports of these goods in 2022-23 nearly doubled compared to the 2016-2020 average. Why would an economy whose industrial output has declined by 26 per cent since 2020 need a substantial increase in imports of industrial inputs like base metals and chemicals, the Bank asks and “Furthermore, importing high-end consumption goods… does not match the current situation in Afghanistan, where two-thirds of households experience significant deprivation and businesses operate below capacity due to low demand.”

Rather, it suggests that 1 to 1.5 billion USD of goods were, “according to sources and market insiders,” imported into Afghanistan, but “ended up in the Pakistani market instead of being consumed domestically.” These goods were not paid for out of Afghanistan’s foreign currency. The Bank also notes that as the afghani appreciated, the Pakistani rupee has depreciated, in roughly equal measure, further proof of what is happening. The Bank surmises that, following Pakistan’s decision in 2022 to take steps to reduce imports because of a balance of payments crisis, including limiting letters of credit for importers, demand for illegal imports via Afghanistan surged.

Importing goods into Afghanistan through Pakistan and immediately smuggling them back into Pakistan is incentivised by Afghanistan not having to pay Pakistani customs on goods destined for domestic consumption – allowed because it is a landlocked country. Famously, during the first Islamic Emirate, Afghanistan imported (and re-exported) large quantities of goods that were banned, for example, television sets and video recorders. What is called the Afghan Transit Trade never went away under the Republic. However, its magnitude appears to have increased significantly since Pakistan’s attempts to curb imports.

There have been mutterings about all this in Pakistan, with calls to ease restrictions on imports to eliminate the demand for smuggled imported goods (see recent reporting in The Nation) and moves to clamp down on smuggling from Afghanistan into Pakistan (see reporting from Pajhwok). If the Pakistani authorities do manage to prevent or even limit the scam, there would be a knock-on impact on Afghan government revenue – currently, it collects customs duties on those imports – and on the strength of the afghani and so the price of imported goods. Many of these are household necessities – food, fuel and medicine.

The Bank does not mention income coming into the country from trade in counter-narcotics. This has always been considerable. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) calculated that the total Afghan opiate economy in 2021, including domestic consumption and exports, stood at between 1.8 billion and 2.7 billion USD, equivalent to 9-14 per cent of the country’s licit GDP. Since then, in April 2022, the Emirate has banned opium poppy cultivation, processing and trade. It became clear in the autumn of that year, when poppy would have been sown, that the ban was largely enforced. Prices soared, meaning anyone with opium stocks has benefited because, according to Alcis and Mansfield writing in June 2023, trade, including cross-border, was not clamped down on (see also AAN reporting here).

In a new report, Alcis and Mansfield have given figures for the number of people “denied the ability to earn an income from growing poppy in 2023” – an estimated 6.9 million – and say it looks like the ban on cultivation will be maintained into a second year. They report growing evidence that households compelled to abandon poppy in Nangrahar are in economic distress – a pattern also emerging elsewhere, citing “[t]he sale of long-term productive assets, including farm equipment, jewellery, and land to meet basic expenses and send male family members abroad.” Their report also details how traders are now targeted, although not everywhere to the same extent: “The only route that has not experienced a rise in smuggling costs,” it says, “is the journey via Bahramchah in Helmand province, possibly reflecting continued privileges afforded to those in Helmand.” The economic impact of the bans on opium, hashish and methamphetamines is not yet settled; much will depend on how seriously and comprehensively they are enforced in future years. However, income from narcotics has been a significant part of the Afghan economy for many years – helping support the afghani, paying for imports and providing seasonal work and income to millions. Take that away and the repercussions will be severe.

Government revenue

Raising revenue domestically is of fundamental importance to the Emirate. With the Taleban victory in 2021, Afghanistan lost huge amounts of foreign budgetary support and the ability to borrow. As we reported in summer 2022, the Emirate has proved far better at collecting revenue, both taxes and customs, than the Republic had been. At that time, in summer 2022, customs were generally holding up, as were non-tax revenues (this category covers a variety of income sources, including profits from state-owned enterprises, royalties, concessions and fines). Revenues from mining have proved particularly important. Taxes on individuals and businesses were less than under the Republic, presumably because taxable income had fallen. More data has now come in via the World Bank: it said that in 2022, customs were 136 per cent of their 2019 level, while domestic revenues (tax and non-tax) were 67 per cent. As a share of total revenue, customs have also become more significant: in 2019, they were 38.2 per cent of total income, in 2022, 55.7 per cent.

Although the accountability sessions gave no indication of overall revenue generated, many ministries and other government agencies did provide reports of the revenue they had earned in 1401/2022: the Railway Authority said it collected 3.1 billion afghanis, up by 25 per cent on the previous year, and the Standards Authority 2.2 billion afghanis, while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that its revenue was greater by 32 per cent than the target set by the finance ministry.[11] Breshna, the state electricity supply company, said it had raised 33.1 billion afghanis from private customers and 3.5 billion from government agencies and had pursued old unpaid bills and customers who had fiddled their electricity meters. It said that 180 million dollars of unpaid bills were still outstanding, owed by politicians and powerbrokers, many, presumably, not in the country. The sum is emblematic of the petty pilfering that characterised the Republic – the rich not paying for what they used. More than 500 cases, Breshna said, are now with the courts.

However, the Bank said that in 2023, the IEA’s revenue collection has not been so strong; domestic revenues have “struggle[d] due to the weak economy” and the first five months of the year saw “a mere 0.9 percent uptick year-on-year.” Non-tax revenues, it said, “underperformed,” falling to 34 per cent below target, mainly “due to weak collection by the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, a significant [non-tax revenue] contributor.” Where revenues were more buoyant, as in 2022, were in taxes taken at the border, customs duties and Business Receipt taxes;[12] they rose by 13 per cent compared to the first five months of 2022. Customs now account for about 60 per cent of total revenues, mainly from crossings with Iran and Pakistan.

The accountability sessions (but not the World Bank reports) also gave information about two taxes which are not collected by the Ministry of Finance: zakat and ushr, the ‘Islamic taxes’ on the harvest and livestock that were introduced by the Emirate nationwide when it came to power. Acting Minister of Agriculture Mawlawi Attaullah Omari reported that in 1401/2022, his ministry had raised one billion dollars from these taxes. That represents a huge new transfer of resources from rural households to the state. The ministry’s assistant head of finance and administration, Mawlawi Fazal Bari Fazli said contributions were voluntary – although this was often not the experience of interviewees speaking to AAN for its special report on taxation published in September 2022. They described the collection of zakat and ushr as similar in nature to general tax collection and in some cases as it being imposed as a collective tax on a village. Fazli said the money went to the office of Supreme Leader Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada, who then ordered its distribution. He insisted that money was only given to “vulnerable people such as orphans, the disabled and the poverty-stricken” and “no other activity was carried out with this money” (see also reporting by Pajhwok).

Government spending

Because the Emirate has to rely on revenues, the contrast with budgets under the Republic is extreme. The 2019 budget, bolstered by on-budget aid, was 424.3 billion afghanis. In 2022, said the Bank, the budget was 195.2 billion, just 46 per cent of what it had been. In 2022, the Bank also reported that the Ministry of Finance had used reserves of 1.3 billion afghanis to meet a shortfall in revenue, compared to spending.

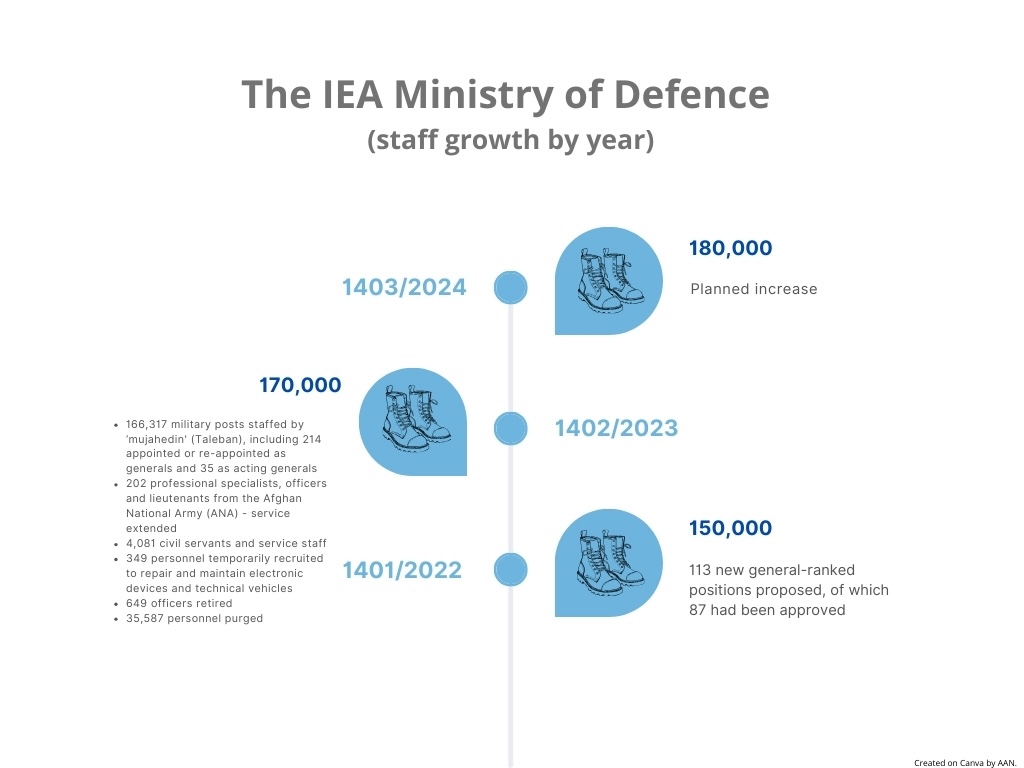

Given these constraints, the Emirate has had to prioritise where it spends money. In general, operational needs come first (94.5 per cent of total spending), far outstripping development (5.5 per cent). Out of that operational budget, a handful of ministries and bodies take the lion’s share, said the Bank. The biggest spenders in 2022 were the Ministries of Interior (23 per cent of total operational spending), Defence (21 per cent) and Education and Higher Education (19 per cent). The other major security agency, the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI), took eight per cent of operating expenditure.[13]

The scale of the money needed to pay the salaries of government employees and armed forces can be seen in some of the statistics on staffing given in the accountability sessions. The Ministry of Interior said it employs 161,000 people (including 1,955 women), a sharp decrease from the 200,000-strong workforce it reported last year (no explanation was given for this discrepancy). The Ministry of Defence, however, continues to grow.

As to the other big spender, the Ministry of Education, while giving no numbers for the size of its school teaching staff, officials did say they had created 100,000 new positions in madrasas across the country.[14]

Among the lowest recipients of money was the Ministry of Public Health. The Bank (with access to data from the Ministry of Finance) reported it was allocated just two billion afghanis, or one per cent of total operational spending in 1401/2022. The ministry, at its accountability session, gave roughly similar figures: its 1401/2022 budget had been 4.2 billion afghanis (3.6 billion for operating and 576 million for development) and it had spent 54 per cent of that. This sum seems very low considering the size of the reported workforce – 111,109, with approval for 500 new posts.[15]

During the accountability sessions, acting minister Dr Qalandar Ebad said that foreign funding represented just ten per cent of the total budget. (He was answering a question from a journalist who cited a warning on 18 August 2023 by the World Health Organisation about “critical underfunding” to the sector and a decision by the International Committee of the Red Cross, reported the previous day, for example, by Reuters that it was to stop paying salaries and running costs for 25 hospitals. It had stepped in with temporary funding to keep them open in 2021, but has now returned “the full responsibilities of the health services to the Ministry of Public Health”).[16]

However, according to the UN, 457 million USD of aid was spent on the health sector in 2022 (see its Financial Tracking Service), equivalent to 38 billion afghanis. Not all that money would have been spent in Afghanistan, but what did arrive was significant. Moreover, cooperation with the Emirate in this sector is explicit. UNICEF, for example, a large recipient of health sector funding, says it works, “under the leadership of Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health… with partners to improve services and ensure quality reproductive maternal newborn child and adolescent health care, as well as expanded programme on immunization services for children and women.” This spending thus looks to dwarf the entire Public Health budget of the Emirate. Also worth noting is the World Bank’s citing “recent unconfirmed reports” suggesting that the Emirate had covered the shortfall in the hospital budget by “reallocate[ing] part of its contingency budget allocations” – funds set aside for expenditure that was not anticipated when the national budget was approved.[17]

One interesting point in the accountability sessions was Breshna reporting that it had paid off its debts. It said that in 1444 (according to the Islamic lunar calendar, equivalent to 1401 and 2022; see footnote 7), it paid off outstanding foreign debts to Uzbekistan (102 million USD), Tajikistan (80 million USD), Turkmenistan (56 million USD) and Iran (65 million USD). It also paid off outstanding debts totalling more than 20 million USD to various domestic electricity production companies.

Helping pay Breshna’s debts was considered in 2021 as a way of helping Afghanistan out of its economic crisis. Although it did not make it into the Humanitarian Response Plan, UNDP did float the idea in its 2021-22 Economic Outlook, published in December 2021, arguing that “An interruption of electricity imports might leave over 10 million people, a quarter of the population, in the dark. International humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan should ensure that electricity imports are not cut, but that, if they are, whatever little energy is produced internally will continue and therefore ease the stark everyday energy poverty of ordinary households.”[18] It appears that the Emirate has managed to pay these debts without such support.

Most Emirate spending is on operating costs, unsurprising given that money is tight. However, within that, there are choices of what to spend money on. The World Bank summed these priorities up:

[T]he ITA [interim Taleban administration] is utilizing available resources largely to pay for security, teachers’ salaries, and core civil and administrative functions while leaving donors to finance healthcare, food security, broader education needs, and the agri-food system.

For donors, this is a political concern, given that their aid to certain sectors frees up the IEA to sustain large, and indeed in the army, growing numbers of men in uniform. Since August 2021, this dilemma has hung in the air.[19]

Development Spending

Financing for development from any source has been minimal since August 2021, given donors’ reluctance to go beyond humanitarian and basic services funding and Emirate revenue constraints. In 2022, according to the Bank, the Emirate initially set aside 10.8 billion afghanis for 66 projects, with 20 more added at a cost of 1.39 billion afghanis, financed from contingency funds. 51 per cent of total development spending in 2022 went on the Qush Tepe Canal (5.46 billion afghanis), a major project to divert water for irrigation from the Amu Darya from Balkh province through Jowzjan to Faryab province.

Where the Emirate does have development funds, it has concentrated them on major infrastructure projects especially those providing irrigation. As well as the Qush Tepa Canal, which is overseen by the state-owned National Development Corporation, the Ministry of Water and Power mentioned several other water projects.[20] The gap between what needs to be done and what can be afforded was nowhere clearer than in the presentation by Breshna. It listed various achievements in the last year: fitting a new transmission cable and thereby tripling the electricity carried from the Kajaki hydroelectric dam to Kandahar (30 to 85 kilowatts) at a cost of just 3.5m USD (compared to a ‘foreign company’s bid of 20m USD); separating the supply of electricity to residential and business customers on industrial parks in Kabul and Nangrahar and improving supply to the latter and; the – soon to be inaugurated – first complete substation designed by Breshna engineers in Chimtal at a cost of 600k USD (compared to a foreign bid of 2.5m USD). It also mentioned some ambitious plans – to finish fitting a cable from Turghondi to Herat to improve the electricity supply to Herat city and another from Arghandi to Ghazni. However, it also lamented the loss of support it used to receive from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, USAID, GIZ and other donors. In the past two years, it said it had received no assistance, and although the company had not collapsed, thanks to its employees and leadership, there was much it could not do.

The accountability session of the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum was also important for any discussion of the Afghan economy. This sector is a major earner for the government and has the potential to push growth. Acting minister Shahabuddin Delawar detailed numerous projects – contracts to prospect for minerals or to mine, already signed or out to tender. However, he also warned that exploiting a mine is time-consuming, with exploration taking at least three to seven years before extraction can start. In other words, the benefits accruing from not yet exploited minerals will take time to realise. Moreover, existing mines depend on market demand; if that falls, for example from Pakistan for Afghan coal this year, revenues will also fall.

However, Delawar was proud of the revenue that mines whose extraction was already underway under the old government were bringing in. His ministry, he said, pays “the salaries and expenses of the national army, the Ministry of Interior, the intelligence agency, and millions of government employees.” He also described how roadbuilding was paid for by mineral extraction. The ministry allocates a specific mine’s revenue for the construction of a specific road, with the ministry paying the Ministry of Public Works a share of the road-building cost. Acting technical Deputy Minister of Public Works Mawlawi Abdul Karim Fateh pointed to several roads, including Kandahar to Uruzgan, Salang to Parwan and sections of the Kabul to Kandahar highway as paid for in this way.

One of the themes running through the accountability sessions was the importance of trade to the Afghan economy, including a trope familiar from the time of the Republic, of Afghanistan as a future regional trading hub. Some of the actions needed to facilitate trade are political. Acting Foreign Minister Muttaqi, for example, highlighted how Foreign Ministry efforts to maintain good relationships with all our six neighbouring countries meant border crossings for goods had been kept open in the last year (for reporting on how damaging closed crossings are to farmers, see this April 2022 report from AAN). He also ascribed the success of the transit trade, with more than fifty-thousand vehicles moving goods across Afghanistan, linking south and Central Asia in the last 12 months, to their economy-oriented policy. However, other actions need money.

For example, acting deputy economy minister Nazari mentioned two large-scale energy projects, TAPI and CASA-1000, which are planned to cross Afghanistan and, he said, had prompted ‘recent’ regional level meetings. Both, however, are stalled. CASA-1000 is a project designed to transmit electricity generated from renewable energy sources in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and onwards to Pakistan (website here). Administered by the World Bank with funding from the Islamic Development Bank, US, UK and Australia, work in Afghanistan has halted since the 2021 Taleban takeover. TAPI, a project to deliver natural gas by pipeline to Afghanistan and on through to Pakistan and India, is also stalled; on 13 October, Afghanistan said it was ready to cover the costs of the Afghan sections (see ToloNews reporting), but disagreements between Pakistan and Turkmenistan over tariffs and costs remain (reporting from the summer in the Pakistan media here).

In summary, despite the Emirate talking up its progress and laying out plans for the future, the Afghan economy is contracting, showing weak demand, deflation and limited public spending, with much of it concentrated on operating costs for the security services. The consequences of all this for households and businesses are the subject of the final section of this report.

How households and businesses are faring

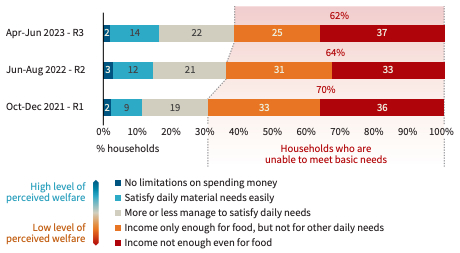

There has been a slight improvement in household welfare since the Bank conducted its last Welfare Monitoring Survey in summer 2022, albeit from very low levels. 62 per cent of households now report that they do not have enough income to pay for food or enough only for food but not other basic needs. That compares to 70 per cent in June-August 2022 and 64 per cent in October-December 2021 (for methodology, see footnote 3). Those figures indicate some recovery following the surge in the number of Afghans living in poverty caused by the collapse of the economy in 2021. However, that still translates into over half the Afghan population living in poverty, a level that is “similar in magnitude,” said the Bank, to what was observed before the regime change, at a time in which the intensity of conflict in Afghanistan was at its all-time high.” Poverty rates are highest in urban areas, the Bank said, although in the countryside, families are vulnerable to the vagaries of the weather, exacerbated now by the climate crisis.

Source: World Bank Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Surveys: Round 1 (Oct-Dec 2021), Round 2 (Jun-Aug 2022), Round 3 (April-June 2023).

The Bank attributed this slight improvement in welfare to remittances having doubled since 2019, the inflow of humanitarian aid and some recovery in wage rates following their sharp fall in 2021. However, it also said, chillingly: “Recent gains in welfare have come at the cost of possibly exhausting all coping strategies and household resources.” In other words, many households have survived until now only at the loss of any resilience in the face of future economic shocks. That could be savings spent, debts incurred, belongings or land sold, young men sent away to work and boys taken out of school to work. Daughters may also have been married, either at a younger age or to unsuitable men (at the most extreme end, this involves child marriage (see AAN reporting here).

The Bank details how extra labour is being mobilised by women doing paid work – three times as many as in 2020 – primarily working at home producing textiles and garments and processing food to sell. The change is especially noticeable in rural areas, it said, where the share of women working in manufacturing increased from 15 per cent in April-June 2020 to 39 per cent in the same months in 2023. This is at the expense, it says, of women’s share of employment in agriculture. For Afghan women, almost all work in manufacturing – 96 per cent – is done at home. At the same time, population growth means the workforce is expanding faster than the economy can provide jobs: one in three young men, the Bank says, are currently unemployed.

The strengthening of the afghani has reduced the cost of imported goods, one factor causing prices to fall. This, in turn, translates into higher real wages for those in work, ie their wages can now buy more. However, while deflation has brought short-term relief, there is a danger of damaging longer-term consequences, says the Bank. When prices are falling, there is an incentive to delay purchasing until prices fall further. Reduced demand can lead to the private sector hesitating to invest, while a deflationary spiral could cause lay-offs. The Bank warns that “recent firm surveys already report a drop in demand as [their] most significant constraint.”

Many businesses are struggling to operate at full capacity. In the third round of the World Bank’s Private Sector Rapid Survey (March-April 2023), it found only just over half of the firms surveyed were fully operational, with another third operating below capacity. Small firms and firms owned by women were disproportionately affected, with only one-third fully operational, compared to 74 per cent of large firms and 58 per cent of firms owned by men. The biggest constraint firms reported was dampened demand, followed by uncertainty about the future and limited banking system functionality. For firms owned by women, they reported that their main constraints were struggling with Emirate restrictions on women’s economic activities and the limited availability of cash and liquidity. Companies also reported a less efficient payment system, the increased cost of doing business, poor availability of imported inputs and difficulty securing loans. Businesses continue to suffer from the strain on the Afghan banking system caused by the reluctance of foreign banks to authorise payments to and from Afghan bank customers – despite all the waivers to United States sanctions exempting most transactions (and making them, for foreign banks, legal under US law).

More positively, nearly half of the firms surveyed by the Bank reported an improvement in the security environment, although female owners were twice as likely to report a deterioration in security since the previous survey compared to their male counterparts.[21] Many firms also reported that their businesses “did not have to pay any unofficial payments or bribes” when paying taxes, clearing customs, participating in public procurement, or requesting government services.

As to what firms are doing to survive the contracting economy, the Bank said that “dialogue with the [interim Taleban authority] to address potential issues was the tactic most employed by male-owned businesses to lessen potential revenue effects” (not to take so much tax?), although fewer than half said they had managed to resolve their difficulties and less than ten per cent reported a “satisfactory resolution.” Women who owned firms, it said, had “more difficulty” engaging with the authorities and their primary coping strategy has been to allow female staff to work from home. Firms in general, it said, also described ‘survival strategies’ – laying off employees, shrinking investments and using hawala agents for making payments, especially for import-export, rather than banks. Those first two strategies – laying workers off and limiting investment – are profoundly worrying since they lay the path toward further shrinking demand and inhibitions on economic growth.

What next?

The Afghan economy has now contracted for two successive years. The current apparent stability feels very fragile in the light of multiple potential threats – from climate change, further reduction in aid, Pakistan clamping down on the import-export scam, prolonged deflation, large numbers of Afghans being forcibly returned from Pakistan and the shock of the ban on opium cultivation to the household income of multiple small and large farmers and landless labourers, and to the national economy. High population growth already outstrips any hope of the Afghan economy providing enough jobs. Then there is the self-inflicted wound of restricting women’s access to paid work and the decision not to educate girls beyond primary schooling, which says the Bank “further lower Afghanistan’s growth prospects.”

Growth is needed, as the Emirate recognises, but it is difficult to see where it might come from. Mining might eventually provide it. Better rain and snow this winter and spring should bring bigger harvests and grazing for livestock in 2024 than has been the case in recent years, but climate predictions are for more frequent droughts. Out-migration, which reduces pressure on employment and services and should boost remittances, is harder than ever for Afghans to undertake. Indeed, many living in Pakistan are threatened with forced repatriation. Major infrastructure projects, which could provide energy, irrigation and better connectivity, are difficult for poor countries to fund without international development aid, which is currently unavailable because of the political choices of both the Emirate and the major donors. Constraints on revenue also limit what the Emirate itself can do, even on a smaller scale, to boost development, although some might question its spending choices; half of government spending going to the security services at a time of peace may keep supporters loyal, but hardly helps the economy.

Deploying development aid, lifting sanctions and recognising the Emirate would all help free up the Afghan economy. For that to happen, there would need to be movement, by the Emirate and/or foreign powers, on a whole range of issues, from IEA policy on girls and women and the make-up of its government to its relations with international jihadist groups. The prospect of either side backing down on these issues seems, for the moment, small. Yet, without some break to the impasse, it is difficult to see how the economy can escape what the Bank has forecast – at best, stagnation and at worst, further contraction.

Edited by Martine van Bijlert

References

| ↑1 | The Emirate has moved Afghanistan’s financial year back to the Afghan hijri shamsi (Islamic solar) calendar, with every year starting on the Spring Equinox (21 March) and year 1 dated to the Prophet Muhammad’s flight to Medina. For simplicity’s sake, the World Bank has continued to map the Western calendar onto this, so that, for example, it terms the current year, 1402 (21 March 2023 to 20 March 2024), as 2023. Occasionally, in the accountability sessions, officials also referred to the Islamic lunar calendar (hijri qamari), which starts from the same year, but counts a year as 12 lunar months |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | As well as AFMIS, the Bank’s monthly Afghanistan Economic Monitors cite ASYCUDA, the computer programme which tracks customs data and the Ministry of Finance, official statistics on prices and trade from the National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA) and data on exchange rates collected and reported by the Afghan Central Bank. The Monitors also cite prices and wage data from all provinces collected by the World Food Programme and data on the availability of foreign exchange and cash from 22 provinces collected by the World Bank’s Third Party Monitoring Agent |

| ↑3 | The first two rounds of the survey took place in October-December 2021 and June-August 2022. The latest survey, conducted April-June 2023, included new information on “a limited set of consumption items and assets used to estimate monetary poverty.” The Bank said it had reinterviewed households previously contacted by the Income, Expenditure, and Labour Force Survey, which was run by the Republic-era National Statistics Information Authority in 2019-20 and 2021. For that survey, 12,811 unique telephone numbers were collected from 318 districts out of 339. About half of the original households could be recontacted; failure was usually because the phone was not working or not active. See pp 25-33 of the Bank’s latest Welfare Survey for more information about methodology. |

| ↑4 | The accountability initiative was pioneered by the second Ashraf Ghani administration, with the first sessions of its Government Accountability to the Nation Programme held in 2020 and then again in 2021. All the sessions, from both the Emirate and Republic, can be viewed on the Government Media and Information (GMIC) YouTube channel. |

| ↑5 | The figures and details quoted in this report from the various accountability sessions were communicated verbally and taken from video transcripts and may contain unintentional inaccuracies. |

| ↑6 | There are notable exceptions: Hazaras continue to be targeted in sectarian attacks, most recently in the bombing by ISKP of a sports club in the Dasht-e Barchi neighbourhood of Kabul, which killed four people and injured seven (see reporting by France 24 here). It is also now more difficult for unaccompanied women to travel because of IEA restrictions. |

| ↑7 | For more detail and discussion, see AAN’s March 2022 report, ‘A Pledging Conference for Afghanistan… But what about beyond the humanitarian?’. |

| ↑8 | 2019 is the most reasonable year to compare, given that needs and assistance increased in 2020 and 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. |

| ↑9 | See the author’s 2020 report, ‘The Cost of Support to Afghanistan: Considering inequality, poverty and lack of democracy through the ‘rentier state’ lens’ which looked at how the magnitude of unearned income flowing into Afghanistan distorted both the state/citizen relationship and the economy. |

| ↑10 | In January-July 2023, exports consisted of vegetable and fruit products (55 per cent of total), coal (22 per cent) and textiles (16 per cent). While coal exports fell by 12 per cent compared to the same period in 2022, exports of textiles increased by 49 per cent and food exports by 2 per cent. See pages 27-8 of the Bank’s report for greater detail on exports and imports. |

| ↑11 | Revenue collection during 1402, as reported by ministries and government bodies during the accountability sessions of August 2023:

Breshna: 33.12 billion afghanis from private customers and 3.5 billion afghanis from government customers, including past debts. It also reported it had paid debts of 303 million USD to neighbours and 23 million to domestic companies. Ministry of Defence: 13 million afghanis net (127 million Afs gross) Ministry of Foreign Affairs: 32 per cent more revenue than the target set by the Ministry of Finance. Ministry of Higher Education: 207 million afghanis Kabul Municipality: 4.2 billion afghanis in the last 11 months, “far more” than previous years and with a plan to increase these revenues. Railway Authority: 3.1 billion afghanis, up by 25 per cent Standards Authority: 2.2 billion afghanis Ministry of Transport and Aviation: more than 8.9 billion afghanis Ministry of Water and Energy: 3.7 billion dollars for specific projects |

| ↑12 | The business receipt tax is an inland tax but collected on imports through a withholding mechanism at the border. Firms can later file for adjustments, but generally nobody does; rather, it is subsumed into the business as a cost. |

| ↑13 | A few ministries and bodies gave figures for their budgets during the accountability sessions, including:

Ministry of Hajj and Awqaf 1402 operating budget 1.4 billion afghanis Ministry of Martyrs and Disabled 1402 budget 12 billion afghanis 1401 budget: 13.5 billion afghanis (9.5 billion used/4 billion remained and taken back by Ministry of Finance; it said it had reached 75 per cent of beneficiaries). |

| ↑14 | Other ministries and bodies reporting increases in staff during the accountability sessions were:

Ministry of Hajj and Awqaf 1402: 9,870 staff, of whom 7,736 were religious workers – khatibs, imams, muezzins, mosque cleaners; this includes 2,200 new religious employees and 370 new non-religious employees and contractors. Ministry of Martyrs and Disabled 1402: 883 posts added (as of the accountability session, 555 had been hired), which would equal 1,969 (in 1401, staff was reported to have increased from 638 to 1,086). Ministry of Public Works 1402: 2,637 staff, compared to 2,185 staff reported for 1401. Transport and Aviation 1402: 4,450 staff, compared to 2,339 staff reported for 1401. Academy of Sciences 1402: 521 staff (304 scientific, 118 administrative, professional or technical, 99 service staff), this includes 50 new posts. The following ministries and bodies mentioned their current staffing levels during the accountability sessions: Land-grabbing commission: 510 staff; Ministry of Economy: 964 staff; Ministry of Mines: 2,425 staff plus 818 at Afghan Coal Enterprise and 900 at Afghan Gas; Environmental Protection Agency 1402 staff: 700; and Supreme Court: 14,024 staff (2,917 judges, 1,785 administrative, 1,394 service jobs, 830 in the Law Department; 7,098 general security and executive posts related to the courts). It said the tashkil (authorised workforce) was complete and would not increase. |

| ↑15 | If the Bank’s figures for the operational budgets for Interior, Defence and Public Health are divided by the number of staff given for each ministry at the accountability sessions (a reasonable metric, given that salaries are the main part of operational spending), Health is a clear outlier: Interior is spending an average of 262k afghanis per person, Defence 231k per person and Health just 33k. |

| ↑16 | The ICRC’s Hospital Resilience Project supported 33 hospitals with a total capacity of 7,057 beds, reaching about 26 million people. The support included “paying the salaries of nearly 10,500 health workers (of whom around one-third are women) and buying medical supplies to limit the disruption of treatment of patients. It also includes cash assistance to buy fuel to run ambulances, ensure power continuity, provide food for patients and carry out necessary maintenance work.” |

| ↑17 | According to the Bank, a quarter of the entire 2022 budget was allocated to contingency codes, amounting to one-fifth of the total operating budget and one-third of the total development budget. They were concentrated in three ministries: Education, Interior and Defence. Contingency funds can be controversial because spending them is discretionary and whoever controls them can spend them as they wish, with little oversight or transparency. During the Republic, when contingency codes took up between about 6 and 11 per cent of the budget, there was condemnation of the power they gave the president, the lack of parliamentary oversight of how they were spent, and some scandalous examples uncovered by the media of where the money actually went. See, for example, this 7 December 2020 Etilaat-e Roz report alleging spending on ‘personal purposes’ such as “hundreds of millions of Afs from [the contingency code, 91 that] have been spent on buying and renting houses, armoured vehicles, apartments, [air] tickets, medical expenses, cash benefits [to senior officials] and other personal expenses.” |

| ↑18 | This risk of interrupted electricity imports was also cited fleetingly in the UN’s Transitional Engagement Framework (page 5), published on 26 January 2022, which it called “the overarching strategic planning document for the UN system’s assistance in 2022.” Some foreign donors liked the idea of assistance via the conduit of paying money to Afghanistan’s neighbours rather than getting ‘embroiled’ in the, to them, more messy policy decisions of sending aid to Afghanistan, given their reluctance to help the Emirate. |

| ↑19 | For more discussion on this, see the recently published ‘Aid Diversion in Afghanistan: Is it time for a candid conversation?’ by AAN guest author, Ashley Jackson, and Donors’ Dilemma: How to provide aid to a country whose government you do not recognise by AAN’s Roxanna Shapour, published in July 2022. |

| ↑20 | Head of the Minister of Water and Power’s Office Qari Muhammad Abdul Aziz mentioned work on the Kamal Khan Dam in Nimruz province; the Kajaki Dam in Helmand; tunnels for the Bakhsh Abad Dam in Farah; Shah wa Arus Dam in Kabul province; Tori Dam in Zabul and; Pashdan Dam in Herat. |

| ↑21 | In round 1 of the Private Sector Rapid Survey, conducted October-November 2021, 19 per cent of respondents were women. By the second round (May-June 2022), that had fallen to just under 14 per cent. Round 3 (March-April 2023) appears not yet to have been published. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign