Afghanistan’s retired public sector employees have not received their pensions since the toppling of the Republic and the re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in August 2021. In the almost three years since then, their pleas to the government to start paying what is their due have fallen on deaf ears. In April this year, they were handed a further crushing blow when the Islamic Emirate abruptly announced it was abolishing the pension system and that it had stopped deducting pension contributions from the salaries of current civilian and military staff. That decision diminished the future prospects of existing pensioners ever getting paid. AAN’s Ali Mohammad Sabawoon and Jelena Bjelica (with input from Roxanna Shapour) have been hearing from retirees about their day-to-day struggle to survive and have also been looking into why it is so hard to pay Afghanistan’s pensioners.

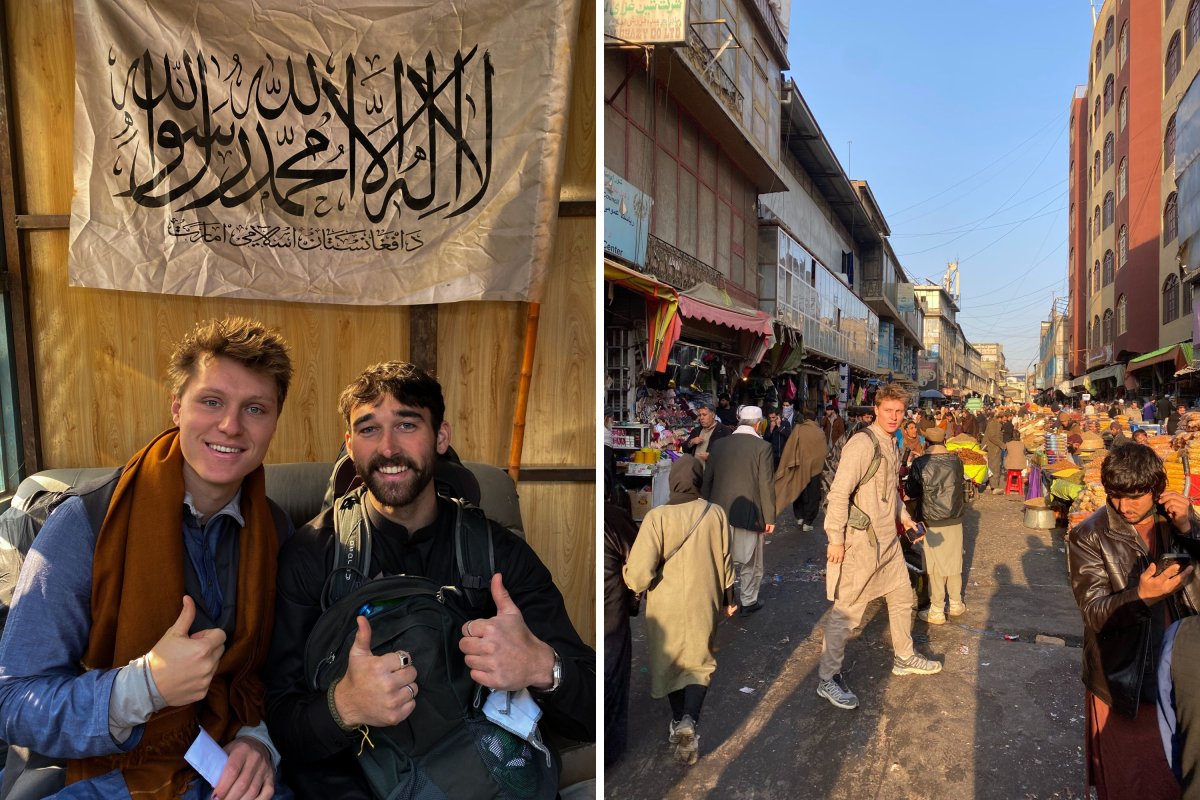

Afghanistan’s public sector retirees have been on the streets, protesting outside government offices, demanding that the government make good on their pensions, which have not been paid for almost three years. Posted on Facebook by Muhammad Sami’i Naderi on 19 May 2024. For more than two years, public sector retirees have been on the streets, protesting outside government offices – see media reports from June 2022, November 2022, January 2023, August 2023, February 2024, April 2024. In rallies that have shown little sign of engendering a positive response, the pensioners have demanded their ‘rights’. The word for rights, huquq, is also used in Afghanistan to mean wages, or in this case, pension payments. The pensioners have not received any of their ‘rights’ since August 2021 when the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) came to power. The end of the payments coincided with the collapse of the Afghan economy and that double blow has pushed many pensioners into poverty. As head of the Afghanistan Retirees Association in Kabul, Afandi Sangar, explained:

We gathered several times to ask the Emirate to pay our pensions. We aren’t protesting, but we’re objecting. We worked for this country. This is money that was taken out of our salaries and it’s our right [to get a pension]. It’s a debt the government owes us. We aren’t asking for charity. We’re asking for our rights. If we don’t get our rights, the only thing we can do is raise our voices.

They have felt that the government had just been keeping them in limbo: “Every time we visit the pension department to get our rights,” one retiree told Pajhwok in August 2023, “they say it will be paid today, or tomorrow,” adding, “We don’t want charity, we… want our rights from the government.”

While the number of current public sector retirees is unknown, the Afghanistan Retirees Association did give a precise number in 2021 – 148,881, made up of 92,254 former civil servants and 56,627 former military (as reported by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL/). A news report from BBC Pashto in March 2024 put the current number of pensioners as far higher: 159,000, including 10,000 women, who include widows entitled to their late husband’s pension. Afandi Sangar summed their situation up with bitter words: “What should the retirees eat? They are not young enough to work. How long should we wait with empty stomachs?”

How are retirees coping?

We wanted to get an idea of how retirees and their families have been surviving since they last received their pensions. We interviewed three women and three men, who are all in their late sixties or early seventies. They told us about their everyday struggles, their search for employment and their reliance on charity. They told us that they feel betrayed and angry, forsaken and stripped of what is rightfully theirs – the small percentage of their salaries that had been deducted year after year, which they expected would fund their old age.

One woman, a widow of 22 years who had been living on her husband’s pension, described how it stopped suddenly in August 2021, leaving her family dependent on the help of neighbours:

If it wasn’t for the community, my four children and I would have died of hunger…. In Ramadan, people helped us – some people brought cooking oil, some brought flour, and some helped us with other food items.

Her experience was not unusual. All our respondents told us in poignant detail about how they have had to rely on the charity of others to – just about – keep afloat. A former public librarian from Kabul, who has six children and retired in 2018, told us how he and his family go hungry most days:

I have nothing to feed my children. I haven’t received my pension since the arrival of the Taleban. I have nothing to eat now. Thanks to the people who gave me some zakat [alms] in the month of Ramadan and at Eid, I have enough [money] for about two months. I don’t know what to do. I’m lost. Sometimes, I think I should kill myself, but two things stop me: one, suicide is forbidden in Islam, and second, how would my death benefit my children?

A former teacher with four children from Kabul province who has been retired since 2015 described how she had tried to make ends meet.

Over the last three years, I’ve sold most of my belongings. We have almost nothing left, [only] what we need, and actually, we didn’t make much money from selling [our possessions].… I am going mad. Sometimes, I go to a private school where one of my former students is the principal. She’s sympathetic to my situation and sometimes, when a teacher is absent, she calls me to cover. Actually, I don’t teach. She asks me to keep the students busy when there’s no teacher in the classroom…. Then she pays me some money. But that money is never enough for my family.

Another retiree, who used to be a mid-level manager (modir) in Kunduz province and who has been retired since 2017, has a long-term health problem and can no longer afford to pay his medical bills:

I’m sick. I have four children and all of them are underage. I have a problem with my lungs and I can’t afford to have an X-ray. Sometimes, people help me buy flour or something else, food or non-food items. When people in the community can’t help, my brother steps in and buys some food for us. Actually, I’m a burden to him because he himself is a poor man. He and his son work in a factory in Kabul. Sometimes, I borrow some money from him to buy medicine.

A former colonel, a pensioner since 2013 in Laghman province, was also worried about health bills, but for his wife: “She has a chronic illness. When I was receiving my pension, I could afford her medication, but now I can’t.” He had taken to selling vegetables to support his family, but says that, in the current economic situation, the money he earns is simply not enough.

The vegetable stall used to support my financial needs in the past, but now all the vegetables in my cart are only worth 2,000 afghanis (USD 30). Suppose I sell all the vegetables, how much [profit] will I make? How will I feed my family and how can I buy medicine for my wife?

Our last interviewee, a woman with three children who worked for the military in Kabul and retired when Karzai was president (she does not remember the exact year), said her family had had no income since her husband fell ill, and the government stopped paying her pension: “My husband used to work as a painter and decorator until about two years ago when he fell ill,” she said. “My pension and his earnings used to be enough to feed our family and cover our other expenses. Now, we have neither my pension nor his earnings.” She said she received a little help during Ramadan from the Association of Retirees, which had received a donation of flour and other food items.

As these interviews show, the impact of the Emirate’s decision not to pay pensions has gone far deeper and wider than just on the pensioners themselves. While public sector retirees account for only about 18 per cent of the 835,900 Afghans of retirement age, that translates into providing support to 150,000 families, or almost one million individuals. For many of those families, the government pension has been a significant source of income. For some, it was their only source. In August 2021, Afghanistan’s pensioners and their families found themselves suddenly immiserated. In reality, though, the non-payment of pensions was the culmination of a crisis which had been brewing for years, masked only by the huge amounts of money paid by foreign donors into the Republic’s budget. When those funds disappeared overnight, it brought the crisis to a head, as detailed below.

Afghanistan’s mounting pension bill

Under the Islamic Republic’s 2008 Labour Law, retirement was set at 65 years of age or after 40 years of service (see the Pashto/Dari version of the law here and the English version here). The Republic’s formal social protection system consisted largely, according to the World Bank, of “a pension scheme for public sector employees and uniformed servicemen [sic] of the military and police, and social safety nets encompassing a number of government and donor schemes that transfer cash and in-kind benefits to various population groups.” Their salaries would have had contributions deducted at source, to which the government also added. The widows, underage children and unmarried adult daughters are also eligible to receive a late husband/father’s pension and are referred to as ‘survivors’ in the laws and documents. Those who have not been in regular employment or who work in the private sector do not receive any social benefits from the state when they reach retirement age.

The country’s pension system has long been in crisis and in 2008, the World Bank launched a programme to support a government-led reform of it (see ‘Afghanistan Public Sector Pension Scheme: From Crisis Management to Comprehensive Reform Strategy’). The Bank put the total of ‘active pensioners’ (either they themselves or their close heirs were registered, alive and receiving a pension) in 2007 at just over sixty thousand people (see Table A4-3 in Annex 4, p55, of the above-cited document).

Unlike pension funds in many other countries that make investments to generate income and so ‘future-proof’ their pension obligations, Afghanistan’s system relied on contributions from current employees and large appropriations from government coffers to pay its former public sector workers. This is because sharia law places constraints on investments that would yield interest or might be deemed as speculative. However, the system was not financially sustainable and was increasingly putting pressure on Afghanistan’s fragile and heavily aid-dependent public finances.

In 2018, a full ten years after the reforms process began, the system was still in crisis. With “pension liabilities – set to swallow the equivalent of a third of the current USD 5 billion budget within 15 years,” the Republic’s then Deputy Finance Minister Khalid Payenda spoke publicly about the urgent need for action. “Previously,” he told Reuters, “they kicked the can down the road and it’s snowballing right now and needs to be fixed.” As part of the finance ministry’s agenda to reform the public sector, it was exploring sharia-compliant investments, such as sukuk instruments (sharia-compliant government-issued bonds) and other measures to try to make sure it could meet its mounting pension bill, which had reached 26.3 billion afghanis (USD 368 million) in 2019 (see the Ministry of Finance’s 2021 Fiscal Strategy Paper).

It was no surprise to many observers, therefore, that retirees stopped getting their benefits after the Republic fell in August 2021. The foreign assistance that had been propping up Afghanistan’s bloated national budget and footing the lion’s share of the pension bill had disappeared overnight and there was simply not enough domestic revenue coming in for the government to both run the country and meet its obligation to retirees.

Pensions and the Emirate

Since taking power, the IEA did not only stop paying retirees, it also reportedly began deliberating what to do with the pension system it had inherited from its predecessors. Currently, there are about 150,000 pensioners. However, that figure was set to rise significantly, given the size of the public sector workforce, both now and under the Republic, as workers reach retirement age.

In summer 2022, about a year after the takeover, the Emirate announced it would look into the sharia basis for pensions. Later, in October 2022, a pension plan ratified by the cabinet was sent to Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada for his approval (as reported by BBC Persian, see also AAN’s readout of this Kabul Now report), with the Ministry of Finance proposing to allocate four billion afghanis (around USD 46 million) to pay for public sector pensions. That was hardly enough to cover the government’s annual pension bill, which, according to recent BBC Persian estimates, stands at 12.5 billion afghanis (USD 175 million). This would also not have included the arrears owed to pensioners for 2021 and 2022. The Republic had budgeted 46.2 billion afghanis (approximately USD 530 million) for these two years – 22.4 billion (USD 257 million) for 2021 and 23.8 billion (USD 273 million) for 2022.However, as the weeks turned into months with no approval from the Supreme Leader, retirees continued to gather outside government offices to demand their long-awaited pensions. In February 2024, IEA Spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahed, told ToloNews that “their appeal has been considered” and that he hoped “their problem will be solved soon.”

Finally, on 3 April 2024, the Ministry of Finance announced that the country’s pension system had been abolished. Under the mandate of a new decree, the government had stopped deducting pension contributions from both civilian and military salaries from the start of fiscal year 1403 (2024/25), with the first contribution-free month being Hamal (21 March to 21 April 2024). The decree had instructed the Ministry of Finance to provide details about the length of service and the funds deducted against pensions for each civil servant or military staff member who was currentlyworking for the government (see a photo of the decree in this BBC Persian report and these Amu TV and Ariana Newsreports), ie not the pension pots accumulated by current pensioners when they were working. This was apparently not mentioned.

Although the IEA has not explicitly explained the reasons behind its decision to abolish the pension system, it was reported that it might hold that it was in breach of sharia. “A number of Islamic scholars do not consider the payment of pension insurance to be in accordance with sharia…. They [the Taleban] had several meetings, including in Syria, on this issue but could not reach a consensus,” professor of economics Muhammad Amir Nuri told BBC Persian. Nuri attributed this to differences of opinion among Islamic scholars about the imprecise nature of pension schemes. “It is not clear that you will receive as much money as you have in your account. Because one often gets more or less than the amount of money in their account…. [If] a person lives longer than the average life expectancy, he will receive more money than the balance in his account, but a person who dies early, if he does not have an eligible heir, [will get] less than the amount of money in his account,” he said.

Meanwhile, the announcement touched off a new round of protests in Kabul by retirees who say that, without state assistance, they and their families simply cannot survive (see, for example, this RFE/RL report).

Human dignity hanging by a thread

Afghanistan’s economic woes have pushed many of its citizens to the edge of endurance – some 24 million are in need of assistance this year alone according to UNOCHA. While 835,900 Afghans are currently of retirement age (65 or older), only 150,000 – those who worked in state institutions – had expected a state pension. Older Afghans, in general, do not seem to figure on the government’s agenda and rarely find themselves on a donor’s priority list. Many are poor and struggling, but the former public sector workers had planned their final years on the assumption that the state would honour their ‘rights’. Instead, they are facing a future with no choice but to rely on charity and the kindness of relatives, neighbours and communities, their human dignity hanging by a thread. What then should they do now?

The woman who, along with her four children, had lived on her late husband’s pension for 22 years, said she felt helpless and powerless:

We ask the leader of the Emirate to give us our rights. Where should we go? Where could we get food, if he doesn’t give us our rights? I am a woman; I can do nothing. What can I do and who will listen to me?

One of the other female interviewees, the former teacher, felt betrayed and angry. She saw no other option but to take to the streets in protest:

In the last days of our lives, we’d rather be respected than punished. Not paying pensions is equal to a punishment. I’m very disheartened. I never thought we’d face such a destiny. We want the government to be kind to us. We’re elderly and cannot support our families. If the government doesn’t support us, we’ll have to take to the streets and raise our voices.

Others worried that protest itself might be dangerous. The retired colonel said he would not be demonstrating, but remained hopeful that the government would eventually start honouring its obligation to pensioners:

Believe me, I can’t protest. I’m afraid that if I protest, I’ll be arrested or injured. If you get injured at this age, then it’s very difficult to recover. I never thought of protesting. What is meant to happen, will happen. But we hope that the Emirate will pay our pensions. We’ve worked for this country. We are not Americans. We are Afghans.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour and Kate Clark

References

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign