The south-western provinces of the country have long been the centre of cultivation up to and including 2023. In 2024, this changed and now 59 per cent of all cultivation took place in the north-east, particularly in Badakhshan.

This is actually an underestimate of Badakhshan’s prominence. The only other province in the northeast to plant more than 100 hectares of opium poppy was Takhar and its contribution was only about two per cent of the regional total.[4] As will be seen below, the IEA believes that UNODC has got its data wrong and that the poppy that was sown in Badakhshan was completely eradicated before the 2024 harvest.

Also of immediate interest in the latest report is data on opium prices. These have now stabilised after steady upward shifts following the Taleban takeover. The long-running pre-ban average was 100 USD per kilo. By August 2023, said UNDOC, they had reached “a twenty-year peak” of 408 USD a kilogramme, surpassing even the price hike following the first IEA ban in 2000/2001. Yet, prices continued to climb. In December 2023, Afghan opiates expert David Mansfield reported they had reached as high as 1,112 USD per kilogramme in the south and 1,088 USD per kilogramme in Nangrahar (see this tweet). Only in early February 2024 did prices start to decline. In June 2024, they were back down to an average of 730 USD, which is still far higher than before the ban, or before the Taleban capture of power.

The extremely high farm-gate prices have produced windfall profits for those who have continued to grow and harvest poppy. The same is true for those who had opium stocks to sell because the IEA did not immediately target traders, although the April 2022 ban also covered trade. In March 2023 (a year after it announced the ban), according to Hasht-e Subh, the IEA issued a 10-month deadline to traders to export opium out of Afghanistan, waiving export taxes. The stated goal of the IEA, they reported, was to end the opium trade in Afghanistan by liquidating all remaining stocks and discouraging future poppy cultivation. However, according to UNODC, trade was continuing in 2023 and Mansfield and Alcis also reported, in April 2024, that:

[O]pium is openly traded in markets across the country even in those areas where there has been no crop since the 2022 harvest; and Afghanistan’s neighbours, including Iran, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, consistently make large seizures of opiates, even arguing that a drug ban is not in place. Evidence shows that the reason that drugs are still being trafficked cross-border is the substantial inventory of opium that remains in Afghanistan.

While traders and richer farmers able to store opium have made huge profits because of the ban on cultivation driving prices up, for land-poor farmers, and the labourers who used to rely on opium for paid work, the ban has been catastrophic. That inequity, between those benefitting from the ban and those hurt by it, could yet give rise to tensions, within or between regions.

All eyes will now be on Badakhshan, the new national leader in opium cultivation, in the coming months, including the Emirate’s. The focus of the rest of this report will be on that province, as we look both at the history of opium there and why many farmers have still been able to continue to grow it, unlike their counterparts elsewhere.

A brief history of opium in Badakhshan

In a major AAN report published in 2016, ‘On the Cultural History of Opium – and how poppy came to Afghanistan’, we quoted researchers like Katja Mielke who suggested that in several parts of Afghanistan, but especially Badakhshan, the “cultivation of opium poppy with the aim to produce raw opium for self-consumption had a long tradition.” It was used, for example, to counter pain, such as from snakebites, and to quell hunger. She and other sources do not say exactly how long ‘long’ may have been, but Jonathan Goodhand, from London University’s School of Oriental and Asian Studies, writes that poppy was introduced to Badakhshan from China and Bukhara via the silk route.[5]

Historically, opium cultivation played a crucial economic role in the province. After the British-Chinese agreement of 1907 had gradually eliminated the century-old trade of Indian opium towards China, Badakhshi traders took the initiative to exploit the large market for opium there, carrying the opium grown in their home province through the Pamirs to Kashgar and Yarkand.[6] However, Badakhshis not only traded in opium, they also grew it. A 1949 UN report mentioned two opium producing areas in the country, “one in western Afghanistan, adjacent to Khorasan province of eastern Iran [which may have been Herat or Farah], and the other in eastern Afghanistan, near Kashmir [probably Badakhshan and Nangrahar].” While the western zone would likely have been oriented towards the Iranian market, where the use of opium as a recreational drug was relatively widespread at that time, the eastern area had certainly developed in order to supply China. Even though that same year, the Chinese borders were closed after the victory of the Communist Revolution, production in Badakhshan continued and exports re-oriented to the rest of the region.

According to Adam Pain’s research on opium cultivation in Badakhshan, “by the 1950s opium poppy was an essential component of the crop repertoire along with wheat and patak (Lathryus sativus) [a legume grown to feed livestock].”[7] The long history of opium cultivation in Badakhshan, along with tradition, brought some to consider its opium to be of the highest quality in Afghanistan (Badakhshi cannabis enjoys similar fame; see AAN reports here and here).

Badakhshan’s opium farmers were, however, to receive a blow in 1958, when the central government made a concerted effort to wipe out opium cultivation, a response to international pressure to do so. However, the country-wide ban, instituted by the king’s prime minister, Daud Khan, was only enforced in Afghanistan’s most northeasterly province. At that time, Badakhshan had 3,000 farmers licensed by the king to grow opium, as Afghanistan in the 1940s and early 1950s was attempting to get an international licence to grow it legally for the pharmaceutical industry. The country’s frequent pleas for the licence at the United Nations had all been denied. Even so, wrote James Bradford, a scholar of drug policies under the Afghan Musahiban dynasty:[8]

The opium ban went into effect on March 21, 1958, stopping all opium cultivation on the nearly 3,000 small opium farmers in the districts around Faizabad, Jurm, and Kishim. All farmers who were licensed by the state were forced to transition to wheat and barley, and unlicensed farmers were being forced to transition as well.

Other provinces were growing opium as well, but were not subject to enforcement. Bradford said the Afghan government singled out Badakhshan in order to make a powerful statement, despite its marginal agricultural economy being quite heavily dependent on the narcotic crop:

In choosing Badakhshan, the Afghan government targeted the one area where opium played its most significant role. It was common knowledge at this point that opium was a staple crop in Badakhshan. Previous decades of trade had raised awareness to the superior quality of Badakhshan opium. Symbolism aside, this prohibition was a serious challenge for the state, not only because of the limitations of state power, but particularly because of the unique challenges the province provided.

For Kabul, keen to make a show of force directed at both internal and international audiences, Badakhshan was perfect. Famous as the centre of Afghanistan’s opium production, it was also very remote with limited state penetration and influence – until the ban, that is. Also, the local inhabitants mostly belonged to minority groups without the potential to lobby within or pose a military danger to the state, as Pashtun tribes had done until the 1940s.

Daud chose Badakhshan because it was inhabited by ethnic minorities who presented less of a threat to the stability of the state. … given the general reluctance of Musahiban leaders to provoke the Pashtun tribal base, Daud chose Badakhshan because it was inhabited by ethnic minorities who presented less of a threat to the stability of the state.[9]

The move devastated households’ food security, indicating the crop’s critical role in the province’s economy. Suddenly, tens of thousands of seasonal workers who had relied on opium harvesting, found themselves jobless. The New York Times reported on 16 June 1958 on the plight of Badakhshi residents:

[T]here [in Badakhshan] 100,000 persons, prohibited by law from growing the opium that has sustained them and their ancestors for centuries, are threatened with destitution … unless the loss of revenue from the highly remunerative opium crop can be at least partially offset.

The 1958 ban did not manage to stamp out opium production from Badakhshan completely. In the following years, as the five-year plan devised by the Afghan government with the help of the UN to provide residents with food aid and alternative livelihoods proved slow in materialising, some farmers resumed cultivation.[10]

The more recent history of opium in Badakhshan

Massive, illicit cultivation of opium in Badakhshan started up again in the 1990s, as elsewhere in Afghanistan, in the context of state dissolution and civil war that characterised Afghanistan during that decade. In the 1990s, Badakhshan also became self-sufficient in terms of drug processing, an important development, given that the province is enclosed by three international borders with China, Pakistan and Tajikistan.[11] As the only province that entirely escaped Taleban control during the first Emirate, it was not affected by the Taleban’s 2000 opium ban. That year, cultivation flourished: in 2001, Badakhshan contributed 79 per cent of the area under poppy cultivation nationally, a sharp increase from the three per cent of 2000.[12] In 2003, when opium production rebounded nationally, Badakhshan remained a top producer, second only to Helmand.

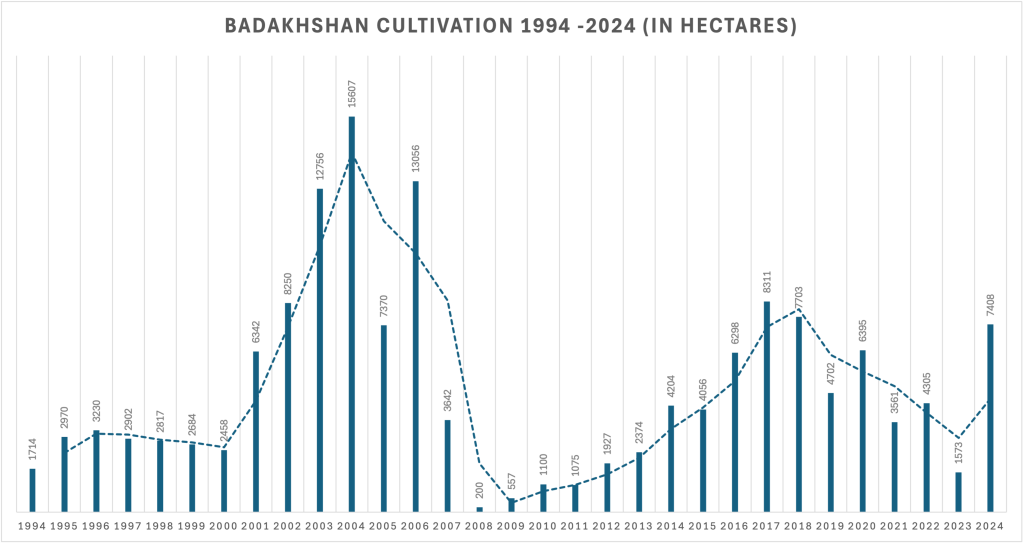

In the decades that followed, Badakhshan remained prominent in opium cultivation: it comprised an estimated 15 per cent of the total national area under poppy in 2003, compared to less than 5 per cent during much of the 1990s (see Graph 1 below, showing opium cultivation levels in Badakhshan province between 1994 and 2024).[13] The UNDOC and World Bank’s 2006 report ‘Afghanistan’s Drug Industry: Structure, Functioning, Dynamics and Implications for Counter Narcotics Policy’ commented:

Isolated, mountainous Badakhshan, where the Taliban were never able to consolidate their control, was relatively unaffected by the drought, and profited from the Taliban ban that affected the rest of the country. Despite a three-fold fall in farm-gate prices, opium poppy cultivation rose again in 2003/04, only to fall by 50% in 2005. Indeed, the increase in Badakhshan and the reductions in Helmand were so pronounced in 2003 that the district of Keshem in Badakhshan was listed as the district cultivating the largest area of opium poppy in Afghanistan. (page 50)

Badakhshan was almost poppy-free in 2008 (meaning it was close to cultivating less than 100 hectares of poppy), thanks to a number of factors – low yields brought about by poor weather and insufficient rotation of crops, development agencies’ assistance programmes and increased counter-narcotics law enforcement in the province. Cultivation eventually picked up though, a pattern shared with much of the rest of the country; it reached 8,300 hectares by 2017, just over half of the 2004 historical high of 15,600 hectares.

This year, opium cultivation has almost reached the levels of 2017, but is still only about half of the historic peak of 2004. This then, is the background to the latest attempts by the central government to ban opium and the reasons why Badakhshan is bucking the national trend.

The IEA’s ban and why its application in Badakhshan has been limited

The IEA’s April 2022 ban on poppy cultivation has been implemented to different degrees across the country and that variation has been the main factor in the changing geography of poppy cultivation. In 2023, the amount of land under poppy in Badakhshan was down, but far less than other provinces, a drop of 63 per cent, compared to drops of 99.99 per cent in Helmand, 97 per cent in Balkh and 90 per cent in Nangrahar (UNODC figures here). Most provinces saw further reductions in poppy cultivation in 2024, or tiny increases. The bounce back in Badakhshan in 2024 was unmatched.[14]

The peculiar situation of the province has pushed the persistence of Badakhshan’s poppy cultivation. Its farmers are poor, typically engaging in subsistence agriculture on small and often otherwise unproductive landholdings. When the ban was introduced, there was no high-yielding alternative crop they could grow, and they also lacked stockpiles of opium, which could have acted as a safety net. The sudden abandonment of opium production was utterly unfeasible. That might also have been the case in other provinces, for example, land-poor farmers in parts of Nangrahar. However, in Badakhshan, the local Taleban authorities, many of whom are connected to farmers through family and social ties, appear to have recognised the looming hardship and been encouraged to show a degree of tolerance (although this has obviously not been officially acknowledged). However, the differing local IEA attitude to enforcing the ban in Badakhshan is also based on other reasons.

Elsewhere, enforcement of the poppy ban has been based less on repressive action but rather mainly on persuasion as to the rightness of the ban and an expectation that rules would be obeyed, with messages conveyed from the pulpits of mosques and by the authorities enjoining local elders to uphold the ban.[15] That method depended heavily on the existence of a strong network of long-time supporters and allies of the Taleban. In Kandahar and Helmand, the IEA has also banked on the support and trust of the major local poppy planters, who moreover, benefited greatly from the ban-induced hike in the value of their large opium stockpiles. In Badakhshan, on the other hand, the insurgency had been far weaker and the IEA found itself trying to enforce a ban in a province where its networks inside rural communities were relatively few, and weak (see AAN’s themed report about IEA governance in the northeast)

When the ban was announced, local IEA officials in Badakhshan – former Taleban commanders who had usually not enjoyed mass community support during the insurgency – were still struggling to expand their influence. This was a region that had never previously experienced Taleban rule and which hosted significant remnants of the old anti-Taleban mujahedin networks. The new authorities were suspicious of the old local elites, who are largely of a Jamiat-e Islami background, considering them susceptible to being enticed to join the armed opposition – which is still active in parts of the province. During the first couple of years of IEA rule, some co-option strategies were put in place in order to win locally influential people over to the Emirate’s side. Local Taleban commanders, for example, were generally left in control of their home districts rather than shuffled around the province or even outside it – which is common practice elsewhere in the Emirate – in order to help them consolidate their local power bases. Moreover, veteran ‘tier 1’ Taleban leaders who hail from Badakhshan, like Chief of Staff Fasihuddin Fitrat, despite holding top-ranking positions in the IEA at the central level, have also been depended upon to solve problems and supervise policies and appointments in the province.

This comparatively secluded provincial political life contributed, at least for a time, to sheltering Badakhshan from the full enforcement of the opium ban and – together with the pressing economic needs of the residents of this poor mountain province – has allowed for a continuation of poppy cultivation in the province. Remarkably though, poppy growing in Badakhshan increased as a percentage share of the land area nationally under cultivation between 2023 and 2024 at precisely the time when the central government was bringing governance of the province more into line with the rest of the country.

Eradication in 2024

At the end of 2023, a reshuffle of the provincial authorities brought outsiders to govern Badakhshan for the first time. This coincided with the realisation or acknowledgement that, unlike the rest of the country, Badakhshis were still sowing and harvesting poppy. That posed a challenge to the IEA’s credibility and risked undermining adherence to the ban elsewhere. It spurred the government into pushing for greater eradication efforts in spring 2024. The newly-appointed provincial governor, Muhammad Ayub Khaled and his entourage, all men from Kandahar, found the local Taleban district authorities unwilling or unable to cooperate with the eradication campaign: in May 2024, Taleban troops from Kunduz and other nearby areas were brought in and tensions with the local farmers arose, leading to violence.

Farmers protesting in the districts of Argu and Darayem were met with violence, with some shot and killed in early May 2024 (see reports by Pajhwok and CIR), while a few days later, an IED attack (claimed by the Islamic State Khorasan Province, ISKP) killed three members of the IEA security forces sent to support an eradication mission (read AP reporting here). Eventually, the IEA’s unofficial plenipotentiary for Badakhshan, Fasihuddin Fitrat, arranged mediation and managed to defuse the situation. Eradication carried on in full swing for a few weeks and then continued sporadically throughout the rest of the spring and early summer; the protesting farmers obtained a minor but significant concession, that only local Taleban troops were to engage in it.

Faced with the need to cancel the impression that Badakhshan was being allowed to get off lightly from the ban on narcotics, it is no wonder that, contrary to UNODC reporting, the Emirate has been adamant that the 2024 eradication campaign in the province was carried out thoroughly and successfully. For example, in a response to the UNODC survey, the Ministry of Interior insisted that:

According to your report, the highest cultivation is in Badakhshan province. However, our regional reports indicate that the cultivation is concentrated in the districts of Argu, Khash, Jorm, Darayem, and Shahr-e-Bazarg, where the fields have been completely eradicated. The issue of eradication has been a major concern across all provinces where opium poppy is being cultivated.

Unfortunately, the UNODC office did not mention the eradication of opium poppy fields in its 2024 report. As you are aware, security forces in all provinces have taken serious actions against opium cultivation, compelling farmers not to grow poppy on their fields.

Our regional information indicates that approximately 16,000 hectares of opium poppy have been eradicated since the end of 2023 until now. Of these, around 6,000 hectares were measured using GPS technology. All GPS data has been shared with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). However, after reviewing the GPS data, it was noted that some GPS points were recorded multiple times on the same date due to GPS devices being left on, which resulted in inaccurate data collection. In some instances, barren land and other crops were mistakenly classified as poppy fields. While there may be discrepancies in the GPS data, this does not invalidate all the figures.

If opium poppy eradication efforts in Badakhshan province had been conducted with the technical cooperation of UNODC, it is likely that accurate GPS data for more than 7,000 hectares would have been recorded. The lack of cooperation from the UNODC office has negatively impacted these eradication efforts.

…

In Badakhshan, all opium poppy fields have been eradicated and your data should accurately reflect the situation, considering that the eradication process is ongoing, and images may have been taken before this was completed.

The IEA claim that the eradicated area equalled the totality of poppy cultivation in Badakhshan contrasts, however, not only with UNODC but also satellite imagery provided by Alcis and reports by locals. According to villagers from the main poppy-growing districts of Badakhshan of Argu and Darayem interviewed by AAN, eradication in 2024 was not full-scale, but rather ended up targeting mostly easy-access areas such as the outskirts of cities and stretches along the main roads, or those areas where farmers and landlords had no connections inside the provincial government to resort to who could help to save at least part of their crop. Locals also alleged the involvement of local officials involved in counter-narcotics operations in influencing which poppy fields were selected for destruction, keeping the eradication teams away from their own turf and even directing teams against their rivals – something also seen under the Islamic Republic.

The current sowing season – autumn 2024, and spring 2025

After last season’s eradication campaign, carried out on the crop that was harvested in late June/early July 2024, all eyes were on Badakhshan to see whether farmers would again defy the law. In this province, there are two main times of poppy cultivation. Autumn sowing (tirmai) usually happens in October, with the poppy seeds then staying in the ground under the snow through winter. Farmers will wait for a couple of good autumn rains before sowing, but if it does not rain, they can afford to wait even until mid-November to sow. This type of sowing is usually practised in higher-elevation areas. The second type of sowing, bahari, takes place as the name implies in late winter/spring and is more common in lower-lying and warmer areas where the snow melts earlier and poppies grow more quickly, allowing for an earlier spring sowing compared to higher area. Bahari also brings lesser yields; the main harvest centres around tirmai sowing.

According to locals interviewed, tirmai sowing is certainly now taking place in a majority of Badakhshan districts. The increased risks of opium cultivation, as shown by the eradication efforts in 2024, have not outweighed the incentives provided by high prices and a growing interest in Badakhshan’s produce shown by opium traders from other Afghan provinces. Also, the acquiescence of many local Taleban officers and the farmers’ ability to stand their ground, although at the cost of violence, in front of the eradication campaign, or at least to reach compromises through the mediation of powerful figures at the central IEA level, might have played a role in their decision to sow again.

Moreover, locals complain of the lack of alternative crops and government funding for them, despite promises they say were made at the time of the eradication campaign and more recent attempts to promote the cultivation of the cash crop, hing (asafoetida), a spice used in the Indian subcontinent.[16] Hing is actually not a good alternative to poppy in the short run because, like orchard crops, it takes several years to produce a return – unlike poppy which is an annual.[17] Interviewees said the lack of an alternative was why, in the higher areas of Argu, Darayem, Khash and Yaftal, farmers had already sown poppy. AAN also heard from locals that no action had been taken against the sowing so far: local Taleban officials have relatives or associates in the villages sowing poppy, we were told, and will not stop them. Also, as reported by locals, a number of farmers hit by past eradication have struck deals with district or provincial authorities in order to ensure next year’s crop will not be destroyed – in exchange for part of the profits.

Only in a few districts, where eradication was carried out more massively and many farmers lost the capital they had invested or barely regained what they had spent, does local behaviour appear more cautious. In poorer and less connected areas, such as the upper reaches of Jorm district, farmers hit by eradication simply do not have the relevant connections at the provincial or national level, or the money to bribe themselves out of trouble when and if eradication starts. Hence, according to locals interviewed, many have refrained from sowing the tirmai crop.

However, even this successful intimidation could turn sour: rugged and secluded valleys in this area, such as the Khastak Valley, have regularly offered shelter to anti-government groups. Already selected as a redoubt by the Taleban during the insurgency, the area has lately come to host ISKP sympathisers. Left without choices, the local villagers could turn to these armed opposition groups to protect their poppy crops from the central government, again, something also seen under the Republic.

The resilience of the drug economy

Badakhshan might represent an exception across an Afghanistan, where poppy cultivation is still at historical lows, but in the context of the rather integrated Afghan opium economy, the fact that poppy growing continues there is a matter of interest for all Afghan opium traders and the markets in neighbouring countries. Although Badakhshan, first and foremost, remains the key supplier for the illicit drugs markets and the traders in Tajikistan for trafficking onwards through the former Soviet republics,[18] in the past two years, informed locals told AAN, the major drug traffickers from Helmand and Kandahar have entered the Badakhshan market and struck deals with local producers (read also this report by the International Crisis Group). Farmers from southern Afghanistan might have complied with the narcotics ban, out of old alliances and respect for the IEA, but traders from there have been earnestly exploring ways to secure continued supply to their clients, without fully depleting their stockpiles. Thanks to their better connections inside the IEA, the ‘Kandaharis’ (as all Southerners are labelled in the north) have fewer problems circumventing police controls and transporting drugs across the country. According to locals interviewed, the Kandaharis initially tried to access Badakhshi producers directly and cut off local traffickers, for example, by having them arrested. However, after some violence was traded between the two groups, the Kandaharis gave up the idea of completely swaying the Badakhshi market and included the local traffickers, who have their own separate smuggling routes and contacts for taking opiates to Tajikistan – as intermediaries in the deals. Moreover, the higher prices of opium allow for an additional tier of middlemen to fit in without hurting profits.

As a province, Badakhshan is particularly vulnerable to the loss of income associated with the poppy ban. Its economy, always fragile and previously dependent on seasonal labour migration to other parts of the country and to Iran – both options now reduced by Afghanistan’s contracted economy and border closure – would be seriously harmed by a full implementation of the ban there. However, the ban has had consequences everywhere, as we explored when we heard from poor farmers in Helmand in the spring. Persistent high prices and lack of economic alternatives make it increasingly difficult for the IEA to achieve a full, nationwide implementation of the ban – in fact, other poor and peripheral provinces such as Badghis also seem ready to resume poppy cultivation (see footnote 13). That means the major political fallout likely to proceed from the ban on cultivation remaining fully in force might not be limited to provinces where the IEA traditionally faced opposition, such as Badakhshan. Where it leads, other provinces might follow: so far, opium farmers with large landholdings from Kandahar and Helmand have been benefiting from stockpiles, but once these are depleted, the IEA risks alienating many even from that area, which always constituted its major support base in the country.

Edited by Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | ‘Afghanistan Drug Insight Volume 1 – Opium Poppy Cultivation 2024’ is the first of three in the annual series of UNODC reports on opium cultivation, production, trafficking and consumption in Afghanistan and it is a rather short report that shows data collected by UNODC through remote sensing techniques and rural village surveys, as well as through global data collection on drugs (the UNODC Annual Report Questionnaires and UNODC Drugs Monitoring Platform). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The 14 provinces were Kunar, Laghman, Badakhshan, Takhar, Balkh, Faryab, Jowzjan, Helmand, Kandahar, Uruzgan, Zabul, Badghis, Farah and Ghor. For an estimated hectarage for each province, see the table on pages 10 and 11 of the UNODC survey. Poppy-free provinces are provinces with less than 100 hectares in cultivation. The national total includes opium poppy found in poppy-free provinces. |

| ↑3 | Alcis, a company that also monitors illicit crops in Afghanistan, has provided slightly diverging estimates. However, as it is currently revising its data for Badakhshan based on a more refined method, we have not included its estimates in this report. For the latest Alcis estimates for Badakhshan, see here. |

| ↑4 | For UNODC, the northeast comprises four provinces: Badakhshan, which had 7,408 hectares of land under poppy in 2024; Takhar, with 165 hectares after being poppy-free in 2023; and Baghlan and Kunduz, both classed as poppy-free, ie planted with less than 100 hectares of poppy. |

| ↑5 | Katja Mielke ‘Opium as an economic engine: Drug economy without alternatives?’ in Wegweiser zur Geschichte: Afghanistan, Potsdam: MGFA, 2007, 207; Jonathan Goodhand, ‘From holy war to opium war? A case study of the opium economy in North Eastern Afghanistan’, Central Asian Survey, 2000, 19(2), 270. |

| ↑6 | Fabrizio Foschini, ‘Heretics or Addicts: The Ismailis of Afghan Badakhshan caught in the middle of the opium trade’ in ‘Uyun al-Akhbar. Islam, Collected Essays, Bologna, 2010, 241-263. |

| ↑7 | Adam Pain. ‘Between necessity and compulsion: opium poppy cultivation and the exigencies of survival in Badakhshan, Afghanistan’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 2023, 51:4, 902-921, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2023.2216145 |

| ↑8 | James Bradford, ‘Drug Control in Afghanistan: Culture, Politics and Power During the 1958 Prohibition of Opium in Badakhshan’, Iranian Studies, 2014, p14, 19. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.862456. The article explores the process leading to the Afghan government’s decision to implement a prohibition and eradication of opium in the northeastern province of Badakhshan – why Daud chose Badakhshan, the impact of the opium ban on the people of Badakhshan and the future of opium production and trade, as well as the evolution of drug control in Afghanistan under the Musahiban dynasty. See also his PhD dissertation, available here. |

| ↑9 | James Bradford, ‘Drug Control in Afghanistan’, 19. |

| ↑10 | James Bradford, ‘Drug Control in Afghanistan’, 18. Ultimately, the economic marginalisation suffered by Badakhshan in the 1960s and 70s was a primary factor behind the development there of a political movement, Sazman-e Enqelabi-ye Zahmatkashan-e Afghanistan (the Revolutionary Organisation of Afghanistan’s Toilers (usually known as Setam-e Melli or “National Oppression”) which criticised Pashtun hegemony and advocated an economic and political emancipation of the northern minorities. |

| ↑11 | Paul Fishstein, ‘Evolving Terrain: Opium Poppy Cultivation in Balkh and Badakhshan Provinces in 2013’, Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), 2014; Doris Buddenberg and William A Byrd, eds, ‘Afghanistan’s Drug Industry: Structure, Functioning, Dynamics and Implications for Counter Narcotics Policy’, UNDOC and World Bank, 2006. |

| ↑12 | Paul Fishstein,’Evolving Terrain: Opium Poppy Cultivation in Balkh and Badakhshan Provinces in 2013’, Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), 2014. |

| ↑13 | For an in-depth study on opium cultivation in Badakhshan in early 2000, see a report by David Mansfield, ‘Coping Strategies, Accumulated Wealth and Shifting Markets: The Story of Opium Poppy Cultivation in Badakhshan 2000-2003’, the Agha Khan Development Network, 2004. |

| ↑14 | UNODC reported opium cultivation in Badghis as also up, by 241 per cent to 1,255 hectares, and Helmand, up by 434 per cent to 757 hectares. However, these amounts are both dwarfed by Badakhshan’s 7,408 hectares. |

| ↑15 | As AAN reported in March 2024 about opium cultivation in Helmand:

An interviewee in Greshk district said that, last November, during the poppy sowing, the IEA had arrested some people and imprisoned them for between one and three months. He thought this was intended to frighten other farmers into not growing poppy. |

| ↑16 | It is an interesting historical fact that hing was mentioned as alternative crop to opium poppy in the 1958 New York Times article about Badakhshan quoted earlier in the text. |

| ↑17 | Asafoetida is deep-rooted plant from the carrot (umbelliferous) family, which produces a pungent spice widely used especially in Pakistani and Indian cooking. A wild plant, it is now increasingly cultivated, but unlike poppy, which is an annual, it needs several years to mature and produce an income. Harvesting involves tapping the roots to extract the gum, which usually kills the plant. Typically grown on rain-fed or waste ground, hing is also not an alternative to poppy in terms of land use. |

| ↑18 | Neither the seized amounts nor the frequency of seizures on the Tajik-Afghan border in the last two years indicate that any change has happened in the legal regime on drugs in either country, according to the Paris Pact Initiative data. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign