Introduction

For most of the last two decades, Andar district in Ghazni province was the site of intense battles. Its strategic location, lying on Highway One between Kabul and Kandahar and one of the ‘gateways’ to Ghazni city, as well as the fact that many Taleban fighters and leaders hail from Andar, made it a hotbed of the insurgency from its earliest days. AAN has studied this district comprehensively for many years, with reports on the conflict, economy, politics and culture. In 2015, it published, ‘Finding Business Opportunity in Conflict: Shopkeepers, Taleban and the political economy of Andar district’ which discovered how shopkeepers were trying not only to survive the conflict, but also manipulate frontlines and road closures to their benefit and their rivals’ disadvantage. This paper is a follow-up to the 2015 report and also comes up to date looking at how the district has fared since 2021.

It begins by briefly introducing the traditional economic structure of Andar as well as how it was transformed with the invasion of the United States and the installation of a new Republic government which received unprecedented amount of aid and military spending after 2001. It then details how the last years of the insurgency affected the local economy, a time when the conflict intensified and control of territory shifted in the Taleban’s favour. The final section explores the current economic state of affairs in Andar, at what has happened to the bazaars that were forced by conflict to close or move location, and at how in Andar, at least, the re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) has brought security and economic and political dividends.

Background

Historically, Andar had a largely subsistence economy, centred around agriculture and livestock, and to a far lesser extent, remittances from economic migrants. The main crops cultivated in the district have been wheat, beans, potatoes and grapes. People exchanged what they grew within local communities in order to meet their most basic needs. Only a small portion of the harvest was sold abroad, enabling the purchase of goods that were not locally available, such as fuel, clothing, and machinery, like water pumps, generators and radios. Livestock, as the second major economic pillar, provided other essential needs. Cows and sheep supplied food and wool, and their dried dung was used as a fuel, for cooking and warming homes during winter, and as a fertiliser. Donkeys and horses were the main means of transport. Economic migration to neighbouring countries, chiefly Pakistan and Iran, was a third, important economic strategy. Many families had someone working abroad who could send money back home so that the family could purchase necessary goods from the bazaar. For one community elder, life was then far more straightforward:

In the past, all we ate and used came from the community. Life was simple and we didn’t need most of the things that have now became a necessity in life. We didn’t go to Ghazni [city] for months. Even if we had important things we needed to buy, one man from the entire village would go and buy everything for everyone in the village. We didn’t know what oranges, okra or vegetables were. All we ate were potatoes, shkana [onion and potato soup] and natar [a dish of buttermilk and broken-up pieces of bread]. People also didn’t have the kinds of clothes people have nowadays. Unlike nowadays, people didn’t need to go to the doctor for treatment. We had our own, homemade treatments. There were no cars or motorcycles, and so we didn’t need to take them to the mechanic or fill them with fuel. Life wasn’t as complex as it is today.

This equilibrium really began to change in 2001 when Afghanistan drew global attention following the 9/11 attacks, the United States overthrew the Islamic Emirate and the Islamic Republic was established and an unprecedented amount of aid flowed into the country. The exceptionally high levels of development aid and military spending raised living standards and drove economic growth – although always with concerns that the growth was not sustainable. Roads, hospitals, schools and telecommunication services were established, connecting previously isolated and inaccessible rural areas to Afghanistan’s relatively modern and often culturally distinct urban centres, and the world beyond. Andar was no exception to these national trends.

The consumption of imported consumer goods soon became a well-entrenched norm. Local bazaars were the primary benefactors of this phenomenon, with merchants bringing in outside goods from major bazaars in cities such as Ghazni. These local bazaars grew in size and number and the imported goods they sold became more varied. This growing trade meant the bazaar business became a major source of income for people in the district. Hundreds of shops were newly established in the old bazaars and new bazaars were set up in different localities. Most villages saw one or two new shops.

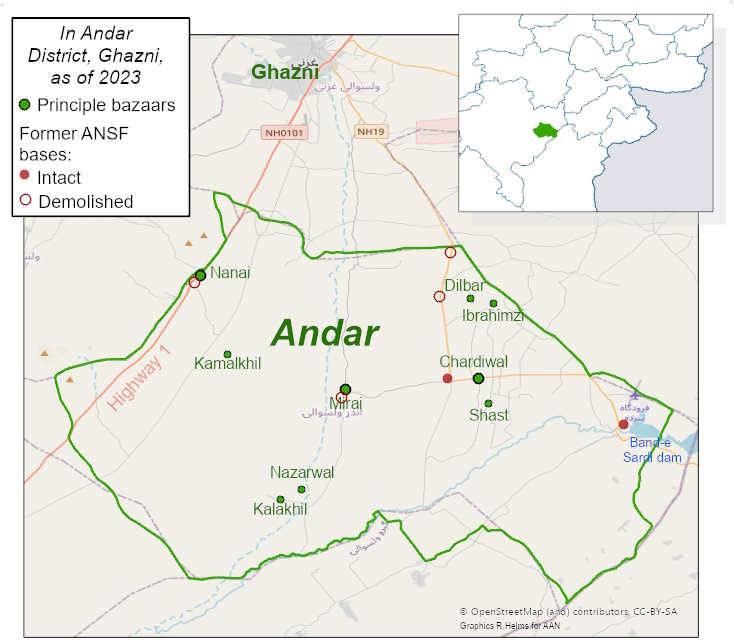

The main beneficiaries of this new trade in Andar were the established bazaars of Mirai, Nanai and Chardiwal. Mirai bazaar is host to Andar’s district centre and government administration, while Nanai is located on Highway One that passes from Kabul through Andar to Kandahar and Chardiwal bazaar lies on the road between Gardez in Paktia and Ghazni highway.

Business in these bazaars flourished until the Taleban insurgency gained momentum in the area. The first blow to the bazaars of this growing insecurity was in 2009, when insurgents closed Mirai bazaar to prevent people from voting in the presidential elections. While the bazaar later reopened, it did not function properly after its first closure in 2009 during all the years of the insurgency (for more details see the 2015 AAN report).

With the conflict intensifying in the district, other bazaars also fell victim to it. Nanai was the site of vicious battles between the Taleban and Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) as well as the US-led foreign forces when they were actively engaged in combat in the period up till 2014. The bazaar, though not formally closed until the end of the insurgency, was a frequent site for Taleban attacks, to the point where people did not dare visit it and it was de facto closed.

Chardiwal, while not host to any government administration, witnessed frequent attacks on passing ANSF convoys travelling to the Bandi Sardi military base and onto Paktika province. It also became too perilous for shopkeepers to do business and customers to visit.

One such businessman in Chardiwal was Anwar, who rented two large shops, selling chickens, vegetables, fresh fruit and beverages. He told the author that his shop was always crowded with customers as his prices were lower than the rest of the bazaar and he always made sure he had fresh fruit and vegetables in stock. Business was booming. Then in 2016, the Taleban planted a landmine in front of his shop in the middle of the night, which the next morning detonated beneath a passing Afghan National Army (ANA) convoy, killing and injuring one soldier and several civilians. Though Anwar survived, he was beaten in the aftermath of the attack by soldiers who blamed him for facilitating the attack.

A few months later, he said he received a phone call from a local Taleban commander who asked him to come to a mosque in a nearby village. When he went there, he was again beaten and imprisoned for a week, this time accused of helping the ANA. Anwar did not go into greater detail, but his story illustrates how vulnerable local businesses could be to the suspicions and allegations made by all of the warring parties.

The more the insurgency intensified, the more the bazaars suffered. However, around 2017, two of the three major bazaars, Mirai and Chardiwal, each received a severe blow. In October of that year, the Taleban besieged Mirai, Andar’s district centre, destroying dozens of shops that were hit by rockets and heavy machine gun fire, and causing the complete closure of the bazaar. Meanwhile, the Taleban also chose to destroy and seal the road connecting Ghazni to Paktika where Chardiwal bazaar is located. This led to Chardiwal’s complete closure as traders quickly vacated the bazaar and businesses collapsed. The ANA conducted several military operations to reopen the road, and also the bazaar, but faced intensive Taleban attack. Almost all operations failed. The entire bazaar was abandoned in the following year, leaving empty shops covered with bullet and rocket holes.

Anwar was one of those traders forced to abandon their shops. He left his thriving businesses and moved all the goods from his shops to his home. “When I calculated the loses [of abandoning the shops], it was over 200,000 kaldar [Pakistani rupees – roughly USD 1,800 at that time]. Most of the goods were wasted; others expired,” he told AAN.

By 2018, no major bazaar was fully functioning in Andar. Nanai remained technically open, although the clashes between the Taleban and Republic’s security forces meant a virtual shutdown. While business people had lost their trading centres they, along with the local population, did not give up, but found new ways to do business.

War also creates bazaars

Andar was not a district where the conflict triggered major displacements. Aside from periods when there were major clashes between the Taleban and short-lived ‘uprising’ or local resistance forces, or sieges of the district centre, the vast majority of people, particularly in areas controlled by the Taleban continued to live in their homes (see an AAN report on the uprisings in Andar here).

When Mirai and Chardiwal bazaars closed, the local population could no longer meet their needs inside the district, so their only option was to travel to nearby Ghazni City. However, that journey was both costly and risky, as one shopkeeper described:

When the bazaars closed, people would go to Ghazni for their needs. They’d need more time and money to go there. Those who had cars were spending an extra 500 afghanis to fuel their cars. Those who didn’t were spending 200 afghanis on the bus fare. Importantly, it took an extra half-hour to get to Ghazni and then another half-hour to return. So, it was far away and difficult to get to. Clashes were routine on the road [to Ghazni] and passengers were often stuck in firefights.

Another interviewee also recounted the importance of local bazaars and the impact of their closure:

In the past, when we needed to repair a water pump or a car, we’d bring it to the mechanics in Chardiwal. Reaching there was easy and took less time than going to Ghazni. But when they closed, we’d travel to Ghazni just to purchase something or repair a machine or a car. [Traveling to Ghazni] was an additional burden on us.

Shopkeepers with businesses in the closed bazaars had to find ways to re-open them. It was their sole source of income and they wanted to respond to the needs of local people. They were also under pressure from the Taleban movement, which pushed shopkeepers to re-establish or move their businesses into the areas it controlled. This was in the Taleban’s interest for a number of reasons: it helped them win people over from the Islamic Republic, painting a good picture of their own then shadow government, as well as meeting their practical needs. The Taleban needed to purchase fuel, use mechanical services for their cars and motorcycles, have private clinics open for their wounded fighters and obtain raw materials for making IEDs and suicide bombs. These bazaars also served as hubs for the movement to gather, plan, drum up support and recruit.

As a result, a number of new bazaars were established in Taleban-controlled areas. In fact, the new bazaars were effectively the same old Chardiwal, Nanai and Mirai bazaars, only relocated to safe areas and splintered into pieces.

Mirai bazaar was steadily moved, from 2017 onwards, to a nearby village named Kamalkhil where a small bazaar had already existed. Another portion of it was established in Nazarwal, another nearby village. Almost everything that was available in Mirai moved to Kamalkhil or Nazarwall – from mechanics, doctors, and tailors, to photocopiers, clothes and mobiles.

The Chardiwal bazaar, for its part, had a similar fate. Initially, it was divided into two major and several minor parts. A substantial portion of it moved to Ibrahimzi, already a small bazaar and known for being the Taleban’s shadow district centre. At the same time, the Taleban re-routed the Ghazni-Paktika highway, away from the paved road and switching to a small, dirt track that passed through Taleban-controlled villages near Ibrahimzi. This, along with competition and the lack of space in Ibrahimzi led some shopkeepers to create a new bazaar, just three kilometres away from Ibrahimzi, along the now Ghazni-Paktika highway dirt track. The new bazaar was called Dilbar.

Anwar said his friends, after several months’ effort, managed to convince him to restart his business in Ibrahimzi. “I didn’t want to re-establish my shop because Ibrahimzi is so far from Chardiwal that I didn’t think I’d get enough customers there,” he said. Though the cost of relocation to a new place was heavy, he said his decision soon paid off and his shop again attracted enough customers in Ibrahimzi.

A short while after that, shopkeepers from the eastern parts of Andar also decided to set up a new bazaar, to meet the needs of the large population in those areas that did not have a replacement for the abandoned Chardiwal bazaar. The new bazaar was located in Shast village, only two kilometres from the paved road, and from Chardiwal. This was created after the Taleban cleared the remaining ANA and Afghan Local Police (ALP) bases from the road, leaving the area almost totally under their control. Shast bazaar quickly became well-known, attracting customers with its newly built shops and ample space, as well as its proximity to Chardiwal. Most of those shopkeepers from Chardiwal who had abandoned their businesses re-established them in Shast bazaar. It also attracted new businesses.

This was not an easy period for shopkeepers or customers and the disruption was sorely felt. Mirai bazaar in the district centre had enjoyed an easily accessible location, with a paved road, mobile networks and government administrations delivering official services. This was in sharp contrast with the new substitutes, KamalKhil and Nazarwall, which had none of these advantages. People living in the northern corner of the district, with its unpaved roads and long distances felt no longer served by anyone. Competition added further complications. The newly established Dilbar bazaar, for instance, became an alternative to the slightly less recently established Ibrahimzi bazaar, and attracted customers from the southern villages of Andar, who had previously had to travel to Chardiwal or Ibrahimzi. As a result, shopkeepers from Ibrahimzi tried to make trouble for the new Dilbar bazaar. According to one resident, they even complained to the Taleban about why the movement had given permission to establish a new bazaar.

By the end of 2018, most parts of Andar, including the district centre, had come under Taleban control. Andar district centre fell to the Taleban in October 2018 which resulted in the reopening of Mirai bazaar. As the fear of conflict abated, Mirai eventually grew back to what it had been, shopkeepers returned and new businesses opened. The situation in Nanai, however, did not improve. The attacks on the highway persisted; the bazaar suffered. The fate of Chardiwal, due to the proximity of two besieged ANA bases, also remained the same.

The new bazaars such as those in Kamalkhil, Ibrahimzi, Dilbar, Kalakhil, and Shast were flourishing, thanks in large part to the relative stability of Taleban control. As the conflict became restricted to only a handful of bases and checkposts, and the bazaars located far from government’s reach in the heart of Taleban areas, security was unprecedented for customers and the shopkeepers who had resettled from Chardiwal, Mirai and Nanai. The bazaars remained open till midnight. For customers, living in uncontested areas, life was relatively peaceful, so long as they did not wish to travel too far.

The end of the war and the economy of Andar today

The Taleban victory in 2021 brought deep relief to the residents of Andar. The burdens the war had placed on them and their economy had been severe throughout the insurgency, but particularly so after 2009. Although Andar like the rest of Afghanistan had seen general economic growth and development because of foreign funds coming into the country, still, local businesses in the district had suffered from the violence and upheavals, the atmosphere of suspicion and resulting harassment from both the Taleban and Republic’s forces. Many shopkeepers were forced to relocate, the cost of which was inevitably passed on to their customers. Others had their shops hit and burned during the violence.

Violence in Andar ended in July 2021, almost a month before the Taleban completed their grip over Afghanistan on 15 August, after the last two military bases in Andar surrendered to the Taleban. The Ghazni-Paktika highway and the road to Mirai were immediately reopened.

When the Emirate was re-established, international aid to Afghanistan immediately dried up, leaving the aid-dependent country’s economy in disarray. After a while, donors again started channelling humanitarian aid to Afghanistan to tackle the dire economic situation. The new authorities, for their part, also took some steps to stabilise the country’s economy (see this AAN dossier on Afghanistan’s economy). The dramatic economic decline after August 2021 has bottomed out, but the economy remains fragile, with service, agricultural and industrial sectors continuing to contract and many families in dire poverty (see here for the World Bank’s annual development update, published this month, and its latest welfare monitoring survey).

However, the contraction of the economy since August 2021 has not affected Afghanistan’s different regions with equal magnitude. Some areas, such as Andar, which were badly affected by the war, have run contrary to the wider economic decline. The re-establishment of the Emirate and the end to conflict, fragmentation and instability in this district appears to have brought growth and new opportunities. While there are no official statistics to prove this, there are still ways to gauge the economic progress in Andar, or at least stability. One is to look at what has happened to the bazaars. They show an economy where people want to invest, where rents have increased and there are customers, indicating a possible increase in disposable income.

With the war over, roads across Andar reopened and the old bazaars came back to life. Mirai bazaar fully re-opened, having been only partly functioning since 2019 because of the broader insecurity and the closure of the paved road. Chardiwal also steadily started to reopen. The highway shifted back to the paved road that passed directly through Chardiwal. Local residents and shopkeepers more assuredly started to re-establish the damaged shops in Chardiwal as the prospects for the ANA and of the fight returning faded. Nanai bazaar also became secure as the Republic’s military base and passing convoys were no longer targets.

The three major bazaars in Andar once again grew larger in size. Businessmen and residents endeavoured to reap the benefits of the new business opportunities and moved their shops back to their original locations. The insurgency-era bazaars have all been abandoned, with the exception of Ibrahimzi and Kamalkhil, which still function, but are greatly reduced. Shop rents mirror the changing demand: in Chardiwalrent for a shop was roughly 50,000 Pakistani kaldar before August 2021, but almost tripled afterwards. For many, such as this shopkeeper in Chardiwal bazaar, they had first to invest before they could reopen:

The door of my shop was hit by an RPG during a clash. It was completely destroyed, along with many of the goods inside. I don’t exactly know whom, but one of the warring sides had entered my shop and looted whatever they could get themselves. The shops of my neighbours were completely burned when hit by mortarsor airstrikes. Shopkeepers suffered a lot of financial losses in these battles. When the war ended, I rebuilt my shop and bought a new door. The repairs cost me 150,000 kaldar [roughly 600 USD at that time].

In both Chardiwal and Mirai, there was also a demand for big new shops. The land surrounding the bazaar in both places belongs to the government and the new IEA administration decided to rent it to people who wanted to establish shops, markets and other businesses. They started giving official permission to rent out plots of land based on a fixed annual rate. This, in turn, created large-scale competition between businessmen. “Everyone was trying to get more land,” said a shopkeeper from Chardiwal. “People were using their personal connections with district [officials]. Some even sold their permission on to others.” The owner of a newly built market in Mirai, explained how he had decided to invest:

Anwar, the shopkeeper who relocated his business from Chardiwal to Ibrahimzi has also moved back. His old shops had been destroyed in the conflict and he had to rent new shops and build his business up again from scratch. Although rents are now twice as high as he paid earlier, he was not complaining: “I am grateful to Allah that now, no one beats me, no one imprisons me and the clashes are gone.”

The single major contributor to the growth of bazaars in Andar has been the end of the war. One resident of the district described how improved security had changed the dynamics of visiting Mirai bazaar in the district centre:

When I was going to the bazaar during the war, I’d try to do my shopping as quickly as possible. At specific times, known to be the patrol times of the ANA, the shops closed and people evacuated the bazaar just to avoid getting stuck in firefights. In particular, we’d go home before darkness, as the police checkposts were harassing people or they, themselves, were attacked. Now, in contrast, I come here whenever I want. Last week, we had a health emergency and I had to bring the patient to the doctor at midnight; so I went to Mirai. There were three doctors on duty. They checked her, gave her medicines and we returned at two in the morning. This would have been impossible two years ago.

Another resident recounts how different a visit to Nanai bazaar now is:

During the war, when we were going to Nanai, we weren’t sure whether we’d come back alive or not. On the one hand, there was a [government] checkpost near the bazaar, and the Taleban used to attack it, without care for the bazaar. On the other hand, checkpost soldiers were making problems for us, checking our mobiles, accusing peoples from our areas of being Taleban and Taleban supporters. They detained whomever they wanted on charges of being a Taleb or a Taleban tarasudchi [spy]. Now, you can go day and night and purchase whatever you want. No one asks you where you come from or where you’re going.

For shopkeepers, the new security environment means they can do business without fear, as one described below:

During the war, we had many problems. The Taleban were beating shopkeepers for selling things to army soldiers. Government forces were detaining shopkeepers for helping the Taleban plant landmines or passing on information about coming tanks, not to mention the arbaki [ALP] who were freely taking whatever shopkeepers had in their shops. Now, praise be to Allah, all this has ended. No one bothers you. No one labels and harasses you for being a Taleb or an arbaki.

Moreover, businessmen who brought goods from Ghazni City to the local bazaars, as one interviewee recalled, were compelled “to pay bribes to several police check posts” along the highway, which also ended with the end of conflict. He explained it below:

The bribes were too high and irregular. If there was a problem with the checkpost, they’d demand a big sum and if you didn’t pay it, you’d have been beaten and even shot. It led many tijaran [merchants] to stop importing goods because the harassment and its effects on businesses were unbearable.

Furthermore, with the cessation of hostilities, people from every sector of society now dare to freely travel to bazaars. During the insurgency, a large portion of people simply avoided traveling to certain areas and bazaars: those who lived under the Taleban were at risk of being labelled as pro-Taleban and harassed by the government side, which controlled the district’s main bazaars until as late as 2017. Then, after 2018, when control of most bazaars in the district fell to the Taleban, those seen as affiliated with the government found their freedom of movement was curtailed. These restrictions fragmented and harmed the district’s economy. Now, the bazaars are bustling, as one interviewee in Mirai described:

Look how many people are here. They are perhaps in the hundreds. Consider me, I’m not rich but come [to Mirai] thrice a week and every time I come, I buy something. Everyone does so. People eat [potato] chips and ice cream, their cars consume fuel. Some come here for the internet, and use credit cards. They buy bindai [okra] and vegetables. You see few people who don’t spend money while visiting bazaars. In fact, those who don’t have money don’t come. Yet, the bazaar is still overcrowded. I think in the next two years it will be difficult to handle the traffic without traffic police.

The economic basis for Andar’s recovery

At the start of this report, we looked at the three traditional pillars of Andar’s economy – crops, livestock and remittances. In Andar, as elsewhere, in certain areas, land could not be cultivated due to the risk of firefights. Several interviewees indicated their harvests had been burned, despite local Taleban ceasefires during harvest, because of clashes between the warring sides. These losses, of crops, homes and lives, are no longer happening.

When I saw people desperately searching for shops, I thought, well, now the war is over, people in Andar are rich, and rents have already soared, so why not invest here more than anywhere else? It doesn’t require much money, and when one sees the rush of people, it seems that things might work out well. I went to the district municipality, and asked permission to build a two-storey market. I started last summer [early 2022] and the work is half done. My estimation was correct: even before my market was completed, many people have asked to have one, two or three shops rented to them.

The persistent problem of drought has harmed the sector, but not so badly as it has in other provinces, including neighbouring ones. Whereas traditionalwatering systems (mainly karizes, or underground tunnels)[1] vanished long ago, most farmers now rely on solar-powered irrigation pumps, which also offer some protection from inflated fuel prices. The running costs are minimal. However, groundwater is declining, so along with the need to dig ever deeper wells and buy an additional solar panel each year to continue to reach the groundwater, there is the looming threat that it may run out or become too deep to access in the future.

However, one of the main reasons that Andar’s economy is functioning well is the other economic ‘pillar’ – remittances. These have probably replaced agriculture as the main sources of household income in the district. There has been a growth in economic migration to the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran and the majority of families, according to the estimates of several community elders, have at least one member working abroad who sends money back home. This has kept the economy running, sheltering it from the worst impact of economic travails inside Afghanistan.

For Andar, there has been another new source of income, post-2021. It was long a base of Taleban support and has been rewarded by the new order. As well as supplying ordinary fighters and commanders, scores of fighters from the district were recruited to the Taleban’s Red Units (special units) and deployed during the insurgency against the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) in Nangrahar. Andar has another advantage. It hosts a grand madrasa, Nur al-Madaris, which is among the most highly respected and oldest religious institutions in Afghanistan, and is famous nationwide among Taleban.

Since the re-establishment of the Emirate, a significant number of residents from Andar have been appointed to senior government jobs. They include the Minister of Urban Development and Housing Hamdullah Nomani, the commander of the Khalid bin Walid Army corps (one of the eight corps) Abu Dujana, the former minister of education Shiekh Nurullah Munir, the Director-General of Dawat wa Irshad[2] Mawlawi Hashim Shahidwror and the Deputy Minister of Education Mawlawi Abdul Khaliq, as well as more than a dozen other mid-ranking officials.

The estimate from multiple Taleban officials and former commanders and fighters in conversation with the author is that thousands of men from the district, who were fighting or working with the movement, or who indirectly supported the insurgency, now hold government jobs. One interviewee, in his 60s, said that, as long as he could remember, “this is the first time so many people [from Andar] hold jobs in government.” Similarly, Andar residents whom the Taleban had previously prohibited from taking up jobs in the NGO sector, with the exception of the health and education fields where they were allowed to work, are now not only allowed, but actively favoured by the Emirate for these positions. The author has come across several incidents where Taleban introduced Andar residents for positions in NGOs operating in Ghazni province, thanks to their past loyalty to the Taleban.

International aid, which was difficult to deliver during the insurgency because of the violence, has also contributed a significant amount to the new economic stability in Andar. Humanitarian aid is delivered to the most underprivileged segment of society that lacks alternative sources of income, lifting the burden of those in direst need, as community leader in his 40s explained:

In Andar, those who have a musafir [someone who has migrated], or land or a job in government or an NGO have a good economic position. But what is good is that those who have none of these, now benefit from aid [mrasty]. The Taleban are bringing NGOs here and helping the poor regularly. They’ve got cards [proving their eligibility for suppor], and get food and cash from various NGOs.

Finally, there are also the costs associated with war and the old regime that no longer apply. Feeding and funding the Taleban used to be a daily burden for Andar residents. Locals were also bound to allocate a certain portion of their crops to the Taleban (ushr) and, in recent years, a tax on some of their assets (zakat). At the same time, they faced demands for bribes from the Republic’s security forces, often at each police and ALP checkpoint along the highway, and from officials in government offices.

The Taleban still collect taxes, but this time as the government, the majority of interviewees agree it is at a lower rate and is less of an annoyance than the illegal bribes they had to pay to the Republic’s security forces and officials. One interviewee recounted: “In the past, we paid taxes three times: first the official tax to the government, second, huge bribes to the police, and lastly, to the Taleban at checkpoints in their areas. Now, only the Taleban take a specific amount of money as tax.”

The end of the war – what has changed?

The cessation of violence had brought the people of Andar deep relief. Farming and trading can go on undisturbed, businesses have been re-established and the district’s affiliation with the Taleban has brought hundreds of jobs. Alongside all that, remittances have continued to flow. Overall, the economy in Andar is relatively stable, with some signs even that it is flourishing. One interviewee, for example, gave an unusual illustration of Andar’s relative wealth:

Since last winter, the number of beggars sitting on the Ghazni-Andar road has been increasing day by day. I’ve talked to many of them and most aren’t from Andar, but come from Ghazni city. Their numbers are growing because they collect a good amount of money – the people of Andar are wealthy and help the poor to a large extent. These beggars do a good business; otherwise, if they weren’t collecting good money, you wouldn’t have seen even one in that area.

Andar’s economy has countered the overall economic decline, at least in comparison with other areas in Afghanistan. So long as remittances keep coming in and there are funds to pay those working in governments and NGOs, the district should be fine – excepting the threat hanging over Afghanistan as a whole, of the climate crisis with its protracted and ever more frequent droughts and the fear that eventually, the solar-powered pumps will not be able to reach water. For now however, the battering this frontline district took for so long is over. Andar has weathered the political and economic turmoil of almost twenty years of war and its residents, whether shopkeepers, farmers or newly-appointed government employees, are enjoying the calm.

* Sabawoon Samim is a Kabul-based researcher whose work focuses on the Islamic Emirate, local governance and rural society.

Edited by Rachel Reid and Kate Clark

References

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign