An explosives specialist conducts mine clearance operations after detecting a piece of metal in Afghanistan. Photo: UNMAS/Cengiz Yar,

An explosives specialist conducts mine clearance operations after detecting a piece of metal in Afghanistan. Photo: UNMAS/Cengiz Yar,

The Taleban’s battle against the well-equipped and well-trained international forces was initially through small-scale guerrilla attacks against government and international targets, using road mines, deploying small squads to capture police and army check posts, trying to persuade locals to join the ‘jihad’ and, gradually, pushing to capture villages. However, as the international military deployment grew after the mid-2000s, particularly because of the formidable air power facing them, the Taleban’s small numbers and small local operations proved insufficient to take and defend territory (see, for example, this article by Theo Farrell). In those early years, the Taleban took up several controversial tactics, including within their own ranks. These included beheadings (dropped early on), suicide bombings (adopted and used continuously during the insurgency and valorised even after the Taleban captured power) and IEDs.

Beheadings of those considered the enemy were adopted as a gruesome way to kill someone and thereby spread fear (see, for example, this Islamic Affairs Analyst’s paper). They were particularly associated with Mullah Dadullah who, along with Mullah Omar, was the first Taleb to publically call for armed jihad against the new government and the foreign forces in early 2003. Dadullah brought his Emirate-era reputation as a brutal but effective frontline commander and, in the early years of the insurgency, was seen as part of the group that had adopted ‘al-Qaeda tactics’, which included beheadings (see this AAN report). The inspiration may have come from Iraq, from where ‘kill videos’ featuring beheadings travelled to Afghanistan in the form of DVDs, encouraging the Taleban, some reports said, to make their own (see, the Islamic Affairs Analyst paper cited above).However, the tactic did not spread much beyond Dadullah, largely disappearing after his death, although there were also later, fairly isolated incidents of beheadings.[1] According to some media reports, the Taleban leader Mullah Omar ordered a ban on this practice in 2008, a year after Dadullah’s death. There were also reports that the Taleban leadership was unhappy not only with his use of beheadings but also another – for Afghanistan – novel tactic, suicide bombings.[2]

The first known suicide bombing in Afghanistan was carried out by two Arab members of al-Qaeda in September 2001 in a lethal attack on the Northern Alliance military leader Ahmad Shah Massud. In 2002, a failed suicide bomb in Kabul was thought to be connected to al-Qaeda rather than Afghans, as was a successful suicide bombing of coalition forces in 2003, which killed three German soldiers. In January 2004, a suicide attack targeted a British forces vehicle in Kabul, which a man claiming to be a Taleban spokesman asserted was perpetrated by a 28-year-old Palestinian (See this RFEl report). Meanwhile, for the first time, in January 2004, an Afghan suicide bomber is known to have blown himself up in an attack targeting a vehicle of the international coalition.[3]

Initially, the idea of suicide bombings caused disquiet and revulsion among many Taleban because of the explicit Quranic order not to kill oneself. Against this, some Muslims have countered that self-sacrifice in the cause of armed jihad is not just permissible, but the best way one can end life. This thinking became the orthodoxy among the Taleban, with suicide bombers established as an everyday ‘weapon’ during the insurgency, and would-be bombers making ‘martyrdom videos’ following training and before ‘deployment’. They have remained a feature of the army of the Emirate even though they are now in power; see, for example, reporting in The New York Times and as Taleban spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahed said on 6 January 2022, “Our mujahidin who are martyrdom brigades will also be part of the army, but they will be special forces.” (as quoted by The London Times).

A brief history of IEDs in Afghanistan

Another type of weapon, the anti-personnel landmine, however, which was used daily during the insurgency and had a longer history than suicide bombings or beheadings, is the subject of this report. These had been used by all parties, governments, armed groups and foreign forces fighting in Afghanistan pre-2001, although after that, the international forces and the Afghan National Army did not use them. They were a familiar weapon to the Taleban and indeed every Afghan. Everyone was fully aware of the costs and consequences of these weapons: according to an estimate by the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, as of 1999, landmines had disabled more than 400,000 people in Afghanistan, and until 1993, had killed or injured 20 to 24 people every day. According to Afghanistan National Disaster Management Authority officials, landmines are still killing and injuring 120 Afghans every month. (see this Pajhwok report). However, what made anti-personnel landmines potentially controversial, and at least questionable for the insurgents, was not the cost they extracted from civilians, but the fact that Taleban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar had banned them during the first Emirate.

This happened on 6 October 1998, when the Emirate issued a statement signed by Mullah Omar “strongly supporting” the Ottawa Mine Ban Treaty of 1997, with “a total ban on the production, trade, stockpiling and use of landmines.” It said they had made a “commitment to the suffering people of Afghanistan and the international community that the IEA [Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan] would never make any use of any type of landmines.” Omar called them “un-Islamic” and “inhuman.”

The Ottawa Treaty (article 2.1) bans anti-personnel mines that are “designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person and that will incapacitate, injure or kill one or more persons.” In other words, the type of mines banned are those which are victim-activated and cannot discriminate between combatants and civilians, making them an inherent violation of a key principle of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) that obliges all parties to a conflict to distinguish between combatants and civilians and to protect the latter.[4] Remote-controlled mines (RCIEDs), which are ‘command-detonated’, are not banned because they can be targeted. The treaty also does not ban anti-vehicle mines, often known as anti-tank mines, designed to destroy or disable vehicles. These contain more explosives than anti-personnel mines and typically require more pressure or weight to detonate. If they have sensitive fuses and function like anti-personnel mines, their use is also banned by the treaty (more information in this Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor article). Omar’s words, however, appear to have banned all types of anti-personnel mines, whether victim-detonated or remote-operated.

For Mullah Omar, who was a veteran of the anti-Soviet war, decreeing anti-personnel mines to be illegal may have been driven by his lived experience of the harm they had done to both civilians and comrades during that war. However, the fact that the Taleban were at that time the de facto government of most of the country and on the offensive might also have encouraged his ruling. Anti-personnel mines were of limited use in the war against the Northern Alliance, given that the Taleban were on the front foot. They were much more useful for the retreating Northern Alliance. Denouncing them as illegal paid tribute to the many civilians who had historically suffered from landmines, put the Emirate on the moral high ground vis-a-vis President Burhanuddin Rabbani’s Islamic State, and brought the Emirate in line with most countries internationally: banning them looked good and demonstrated that the Taleban were an accountable and responsible government, all with little military cost.

Mines had been used by the Soviet army during its nine-year occupation and then by the mujahedin who, according to Laster Grau, first recycled the Soviet mines and then began to manufacture their own explosive devices. Many years later, when the insurgency began, the Taleban also used remnant mines from the Soviet era. After 2006-07, when the insurgency was becoming more widespread, the Taleban began manufacturing more complex and destructive forms of IEDs.[5]

Internal debate gives way to IEDs as a weapon of choice – and to soaring civilian casualties

21 interviews, all conducted during the insurgency between March and June 2021, with a mix of Taleb and local civilian interviewees, point to a debate within the Taleban on the use of pressure-plate IEDs.[6] There was a discussion on whether to use this weapon, given ethical concerns about the harm it poses to civilians. Some considered landmines illegal, such as this Islamic scholar affiliated with the Taleban from the Giro district of Ghazni province who said in an interview in March 2021:

The use of things such as mines that are harmful to ordinary people is prohibited in sharia. If someone [civilian] is killed by a mine, and the mine is placed by the order of the Amir, they must give his family diyat (blood money).

Others came up with sharia-based justifications for their use of what Mullah Omar had declared to be an illegal device, driven by its military effectiveness, as a Taleban IED specialist from Helmand province explained in March 2021:

If it was called haram then [in 1998], it was because there were no invaders, no tanks, no drones, but now there is everything. And we need to kick them out and bring in an Islamic system. It’s therefore permitted in sharia because, without using such tactics, it will be impossible to bring an Islamic order to the country and kick out the infidels.

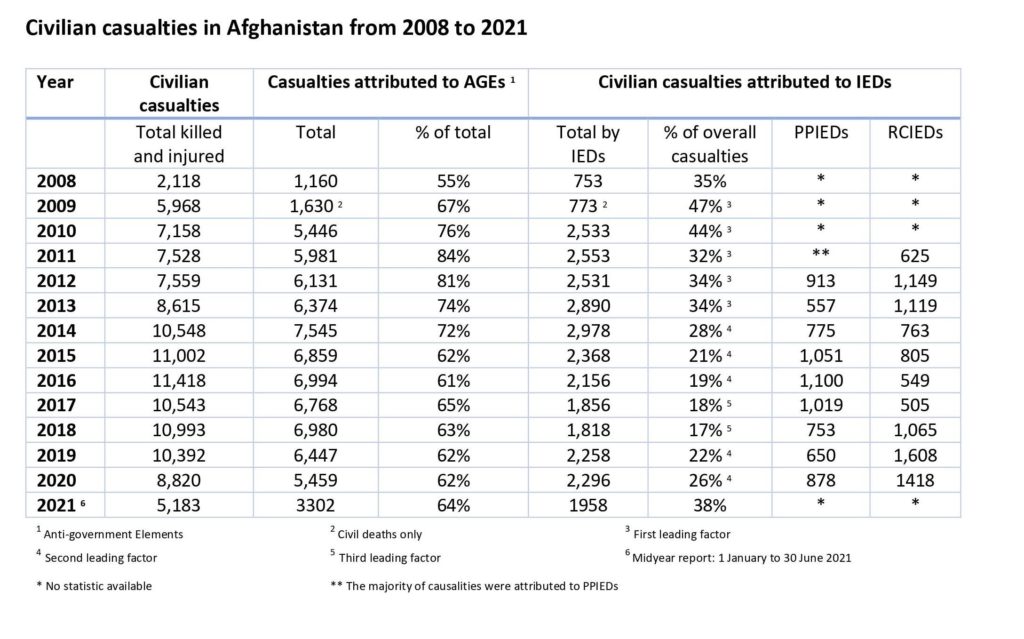

Whatever the ethics of the matter, IEDs became the Taleban’s weapon of choice and were used on a large scale until the very end of the insurgency. In 2010, the Taleban carried out 7,000 IED attacks in a single year.[7] Their use peaked in 2011, when the group’s IED attacks increased, according to a US Army report, to 1,600 in just two months of that year. Civilian casualties soared. Since UNAMA began systematically documenting civilian casualties in 2008, as published in its Annual Reports on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, IEDs were usually the main killer of civilians (in all the years between 2008 and 2013 and in 2021), or the second most deadly (from 2014 to 2016 and 2019 to 2020) or the third (2017 and 2018). Although all types of IEDs caused civilian casualties, pressure-plate IEDs accounted for the majority of these casualties because of their explosive force, indiscriminate detonation and widespread use (see the table below). According to one Taleban fighter interviewed for this report, in March 2021, the group had plenty of IED ‘engineers’ by then: “We have on average five to six IED makers in our local groups – each of which are 20 to 30 fighters strong.”

In the initial years of the insurgency, the Taleban mostly relied on remote and wire-command IEDs. However, since these needed human operators – who were easily detected by NATO – over time, the Taleban shifted to pressure-plate IEDs. They were less risky for the Taleban’s own forces, but much more dangerous for civilians as they explode automatically when any person steps on them, or if less sensitive, when any vehicle drives over them.

For the Taleban, IEDs, especially pressure-plate IEDs, made military sense. They put their fighters in less danger than confronting either foreign or Afghan government forces directly and were an effective weapon in an asymmetric conflict against better-armed forces who had a monopoly on air power. In 2009, 2010 and 2011, IEDs caused about half of all United States troop casualties (45.5 per cent, 51.5 per cent and 43.8 per cent respectively), according to Brookings, leading NATO to launch a counter-IED campaign. NATO troops, the Inter-Press Service news agency reported, spent over 18 billion dollars on this. Despite its efforts, the Taleban’s IED campaign was a significant factor in their resilience and ultimate capture of power.

IEDs and the need not to alienate local support

The initial reason for the Taleban using IEDs was to counterbalance the international and Afghan government forces’ better weaponry and, especially their monopoly on air power, to secure footholds of territory. As long as the tactic proved successful on the battlefield, the Taleban’s use of landmines, widespread and indiscriminate, continued. Eventually, however, other considerations began to emerge.

As the insurgency gained momentum in the early 2010s, the Taleban, at least on a leadership level, became concerned that the insurgency was unwinnable without local support. “Even though the population is often unable to stand up to the Taleban,” as an AAN report in 2011 argued, “in this war, winning the support of local people is seen as crucial – for all sides.” (See page 18 of AAN report on the Taleban Layha or code of conduct.) While the leadership was aware that civilian lives could not be saved entirely (as is always the case in war even when all parties follow IHL), for pragmatic reasons, ie keeping local support, they wanted to reduce civilian harm.

The Taleban never recognised the IHL definition of a civilian as a non-combatant, insisting, for example, that government officials and buildings, clearly civilian under IHL principles, were legitimate targets. Rather, they spoke about the need to protect the ‘common people’. Even so, this protection was not across the board. In their suicide attacks in Kabul, for example, insurgents deliberately attacked purely civilian targets that were not even connected to the government, such as hotels and restaurants. They also attacked government and military targets without regard for passers-by and other civilians inevitably killed and injured. They appeared to regard those living in areas under their control, or potential control, whom they regarded as the ‘common people’ – potential supporters – as worthy of some protection, whereas others, including some urban populations, appeared to be considered low status and entirely unworthy of protection.

Even so, their revised Layha or code of conduct issued in 2010 was marked by a change of tone. It ordered: “…all mujahedin [Taleban] with all their power must be careful with regard to the lives of the common people and their property…” (See page 21 of AAN’s report on the Layha). As to “the general ‘hearts and minds’ policy of the Taleban,” the AAN report continued, it “is summed up in article 78”:

Mujahedin are obliged to adopt Islamic behaviour and good conduct with the people and try to win over the hearts of the common Muslims and, as mujahedin, be such representatives of the Islamic Emirate that all compatriots shall welcome and give the hand of cooperation and help.”

The report argued that a major focus of the Layha was to “restrict the worst brutalities of Taleban fighters: not all methods of warfare would be acceptable.” This was also suggested in another analysis of the Layha which concluded that it was intended, among other reasons, to ensure that “jihadist operations do not negatively impact the Taleban’s public support.”[8] Following the announcement of their spring operation in 2011, Mullah Omar again declared to his fighters that “strict attention must be paid to the protection and safety of civilians during the spring operations by working out a meticulous military plan.[9]

Pressure had been coming from the communities in the Taleban’s rural strongholds from which they recruited fighters, where they felt they enjoyed a large measure of public support and sought refuge and shelter, and where their IEDs were causing the greatest harm. The deaths and injuries to civilians caused by Taleban IEDs were tarnishing the Taleban’s image locally and precipitating criticism in their heartland. The casualties were also sparking widespread condemnation in both the local and international media, human rights groups, UNAMA and presumably behind the scenes, also, the International Committee of the Red Cross. Partly in response to this pressure, the Taleban leadership began to engage in dialogue with a range of political and diplomatic figures, including UNAMA, who were keen to get Taleban policy on IHL, including the group’s use of the indiscriminate pressure-plate IEDs, changed.

UN reporting on civilian casualties was seen, wrote Jackson and Amiri in a 2019 USIP report on Taleban policy-making, as particularly problematic for the Taleban:

On August 15, 2010, the Taliban released a public statement in response to UN civilian casualties reporting. They proposed a joint commission to investigate civilian casualties, comprising members of the “Islamic Conference, UN’s human rights organizations as well as representatives from ISAF forces and Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.” The UN publicly responded that it would be willing to engage in dialogue with the Taliban if it were “premised on a demonstration of genuine willingness to reduce civilian casualties.” This exchange eventually led to the creation of a private channel of dialogue between the Taliban and the United Nations.

In June 2013, the Taleban announced the establishment of a commission for civilian complaints casualties, sitting within the military commission, to investigate incidents caused by all sides in the conflict. It actively supplied UNAMA with information and complaints.

The Taleban, stung by UNAMA’s annual ranking of their fighters as causing the most deaths and injuries to civilians in the conflict, were certainly engaging in a propaganda battle, accusing UNAMA of partisanship, and putting the ‘real blame’ on foreign forces. But were they actually also engaged in trying to reduce their own civilian casualties?

In October 2012, the Taleban issued an open letter to UNAMA about civilian casualties in which they denied that their fighters used ‘live mines’, a reference to pressure-plate IEDs. The Taleban stated that their fighters, “never place live landmines in any part of the country, but each mine is controlled by a remote and detonated on military targets only.” (see the text of the letter in this article – original link not working) The question always was whether such denials represented anything more than words, ie was there any shift in battlefield tactics to try to protect civilians?

Internal debates on pressure-plate IEDs

It seems that at a senior level, the political leadership was convinced of the need to take practical steps to protect civilians in order not to alienate local people – the political leadership here meaning the supreme leader, chief of justice, heads of civilian commissions, and at a lower level, provincial governors and other civilian officials. However, this only happened when the movement was in a relatively better military position, in 2012. That year, according to Antonio Giustozzi: “the Rahbari [leadership] Shura ordered a suspension of the mine campaign to prevent losing political capital among the communities.”[10] What exactly happened, though, is confusing.

Giustozzi reported that the Military Commission did not accept the suspension, so only village-level fronts and governor groups obeyed the order. Furthermore, he said that about six months after the ban, the Taleban in the south began to receive Iranian-made remote-control mines, which could be targeted effectively, and this prompted the Rahbari Shura to lift the suspension. However, a senior Taleban source described to the author how the need for a ban on pressure-plate IEDs had been raised that year by several senior leaders and that the remaining leadership approved it. “There was a ban,” the source said, but it was not issued as “a direct order from Mullah Omar.” He said Omar’s then deputy and successor, Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansur, who took over effectively in April 2013, but officially only from July 2015 after Omar’s death was belatedly announced, had been “among those leaders strongly lobbying to stop using pressure-plate IEDs.” Members of the military commission, though, the source said, were “not in a position to accept an outright ban and proposed instead that pressure-plate mines should continue to be used but that they should be laid more carefully.” Another senior official involved in the discussion gave a similar explanation:

Some mashran [leaders] were against the [use of] pressure-plates and were determined to place a ban on them. After discussing the issue with us [the military commission], however, we told them our reasons why we couldn’t just stop using them completely. We suggested that only in exceptional circumstances, after completely ensuring that civilians wouldn’t be hurt, would we use them. We didn’t reach a conclusion. They insisted on the ban and continued [publicising] it, and we went on with using pressure-plates in very limited circumstances.

Interviews with Taleban fighters suggest an order banning pressure-plate IEDs was disseminated, or at least known about. One fighter from the Nad Ali district of Helmand province, for example, interviewed said: “Pressure-plate mines were banned by our leaders a long time ago. In April 2021, our Amir ul-Muminen told us not to use these types of mines because they cause civilian casualties.” Another Taleban commander from Ghazni province explained how they had used landmines in Ghazni province:

We were told [by senior commanders] that we could only use pressure-plate IEDs in a few exceptional situations. If a road or area was completely free of civilians and we and the enemy [Afghan security forces] were the only ones concerned, then we were allowed to use them. Last year [1400/2021], we used heavy pressure-plate IEDs in Arzu [an area in Ghazni city] to fight because civilians were totally evacuated from there. We also used them on the Qarbagh road after we’d damaged some parts of the road to ensure that civilians couldn’t pass on it. Apart from these exceptions, pressure-plate IEDs weren’t allowed. Our friends used wire command mines more, connecting a five-hundred-metre-long wire and detonating the mine through it.

On the ground, however, any drive to completely cease their use was neither consistent nor sustained. The battlefield priorities of the military wing weighed too heavily on the leadership.

Actual battlefield tactics were shaped by local commanders rather than the political leadership. Even though the political leadership may have wanted to assert control, ensure discipline and move on with a more population-centric strategy, it was also aware that the rank and file would not tolerate too much pressure. Fighters were excessively sensitive when it came to being told what to do on the battlefield, as a Helmandi commander told the author in early April 2021: “If they are ordering such things [the ban on pressure-plate IEDs], then they themselves should fight. We cannot fight on those terms. They aren’t aware of our situation on the battlefield.” The military commission and senior commanders did have more influence on the battlefield, but they were often not convinced of the need to ban pressure-plate IEDs either.

Given the effectiveness of this type of weapon against the enemy and the limited alternatives available, it is perhaps not surprising that Taleban fighters remained hostile to any ban. Meanwhile, the political wing continued to brief that there was a ban and the use of pressure-plate IEDs had ceased. Except for a few exceptions, they attempted to explain away their use by saying they had been laid by local rogue commanders or that they would investigate.

It may have been sensitivity over pressure-plate IEDs, as well as continuing claims of an official ban that led to most attacks using this weapon going unclaimed. In 2016, for instance, the Taleban only claimed responsibility for 49 pressure-plate incidents out of a total of 560 incidents documented by UNAMA. In 2017, they claimed responsibility for only 22 out of 482 UNAMA-documented incidents. It was an indication that the group’s media arm thought it better to remain silent.

Many Taleban commanders also denied accusations that their IEDs caused any harm to civilians or at least insisted that if they did, they were not responsible. They asserted that the claims were disinformation pushed by Kabul and the media, as a commander from Maidan Wardak province explained:

It’s all government propaganda. Our mines do not kill or injure civilians; civilians are not our targets. It is the fatwa [order] of our Amir ul-Muminen that it is not a problem to target whoever is in front of infidels and is sheltering [the ANSF].

The idea that the civilians themselves were responsible if they happened to be harmed by IEDs because they were ‘sheltering’ enemy combatants looks like an attempt to deflect blame. Yet it might have been this sort of thinking that allowed local Taleban fighters to assure their superiors – and themselves – that their IEDs only ‘occasionally’ killed or injured civilians. Mullah Omar, however, appeared to have been aware of this issue, saying in his 2011 Eid message:

If civilian casualties are caused in IED strikes, martyrdom attacks and other operations but the Mujahedin of the area repudiate these allegations while all testimonials and evidence point otherwise then all the suspects should be forwarded to the legal offices.

He went on: “If the same officials persist in their neglectfulness in relation to civilian casualties then more Islamic penalties should be handed out, in addition to his termination from post” (see this AAN report).

Enacting the ban – or not

On the battlefield – the Afghan countryside – the Taleban’s use of pressure-plate IEDs continued. Indeed, according to UNAMA’s 2012 annual report, when the ban was supposedly established, the use of landmines actually increased slightly as that year wore on. Most of the IEDs that were known about, UNAMA said, were victim-activated, with pressure-plate IEDs being the most common. It quoted ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) data that there was no statistically significant difference in the type of IEDs used between 2011 and 2012. “Approximately 70 percent of IEDs remain victim-activated,” it said. Moreover, victim-activated IEDs were most widely used in the southern provinces, where, UNAMA said, “they constitute the vast majority of IEDs used.” In the year of the reported ban, Taleban IEDs caused 2,531 civilian casualties – 868 deaths and 1,663 people injured.

UNAMA was sceptical about Taleban intentions. Certainly, they were speaking more about protecting civilians: 25 of the Taleban’s 53 public statements issued in 2012, UNAMA said, concerned civilian casualties or human rights protection. The Taleban had made a public commitment to protect civilians, denied using pressure-plate IEDs and sometimes asserted that they had taken specific measures to protect civilians in certain attacks. The 2012 Protection of Civilians annual report said:

UNAMA observed a shift in the Taliban’s public messages regarding attacks against Government officials with a greater emphasis on targeting of military objects and promoting ‘insider attacks’. This apparent shift may reflect a heightened awareness by Taliban leadership of a need to both show and address public concern for protection of Afghan civilians and support for a wider political objective related to the peace process and winning Afghan “hearts and minds.”

However, UNAMA added: “While Taliban statements calling on its members to protect civilians are welcome, the situation on the ground has not changed. The Taliban increased their direct targeting of civilians through targeted killings and continued to indiscriminately use IEDs including illegal pressure-plate victim-activated IEDs.”

The following year, however, the number of civilians killed and injured by pressure-plate IEDs did fall, and quite considerably. UNAMA reported that this weapon killed and injured 39 per cent fewer civilians in 2013 than in 2012 (although that still meant a total of 557 civilian casualties, 245 deaths and 312 injured). Those watching the war did wonder if the Taleban had finally implemented an effective ban, for example, AAN’s Kate Clark:

[In 2013], there were some small signs of improvement in Taleban tactics: the number of civilians killed in suicide and complex attacks while still high – 15 per cent of all civilian casualties, ie 255 deaths and 982 injuries – were 18 per cent less than in 2012, even as the number of attacks remained similar. A sign perhaps of better targeting? Taleban orders also led to a decrease in the use of pressure-plate IEDs which are completely indiscriminate, being detonated as easily by a child stepping on them as an armoured vehicle driving across. This move follows a great deal of criticism, not least from UNAMA.

Unfortunately, said UNAMA, casualties from the now more often used remote-controlled IEDs had risen, often because the operator had not taken enough care to protect civilians. In any case, the following year, 2014, the numbers killed and injured by pressure-plate IEDs recovered: UNAMA reported a 39 per cent increase compared to 2013.

After the ISAF withdrawal

Interviewees have suggested that after the withdrawal of ISAF in 2014, rank-and-file Taleban fighters and commanders themselves took some steps to reduce civilian harm. Some local Taleban commanders began increasingly informing local people where they had planted IEDs, and in many cases, they blocked civilian access to mined roads. In Ghazni province, for example, local Taleban were announcing in local mosques that they had lined a road with IEDs and ordering people not to use that road. One Taleban fighter said:

Whenever we plant mines on highways, we block the road. We tell the people in nearby villages; we announce in the mosques and on loudspeakers that the road is blocked. Whoever goes on it and gets killed, it is their fault, because they are informed of mines.

Similarly, after the Taleban mined sections of the Kabul-Kandahar highway, a resident of Maidan Wardak province, interviewed in late March 2021, said they informed the surrounding population: “For the past two years, the Taleban ordered local villagers not to go on the road because we [the Taleban] planted IEDs there. They were telling people to use alternative routes.” A resident of Zurmat district in Paktia Province made similar comments:

The Taleban once blocked our road with IEDs. They told people living nearby not to go on the road and wrote ‘Mainuna di’ [there are IEDs] on the walls. They also put noticeable stones on many parts of the road for anyone who had not heard about the closure. The Taleban also told some people who had farmland nearby to stop people using It [the road].

A commander from Zurmat district, now holding a job in the provincial police, said once the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) became their primary enemy,[11] Taleban thinking changed:

In the time of the Americans, after we were told they were coming for operations, we’d encircle more than a dozen of villages with fishari mines [pressure-plate IEDs] and weren’t telling locals [about them] because of jasusan [informers]. They often targeted ordinary people and even our own comrades, but once the Americans were gone, we were good enough at fighting the Afghan army, and also to decrease the harm to locals, we didn’t use mines in the villages.

Another Taleban interviewee said which mine they used depended on the enemy: “We were told by our [senior] commander that we can use them [pressure-plate IEDs] when Americans and [Afghan] Special Forces w coming for operations. We only used those mines [pressure-plates] after our spies told us that there was an American and commando operation.” In normal situations, he said, they mostly used remote and wire-commanded IEDs, along with mobile-call-activate IEDs. He said he did not, personally, know of any formal bans on pressure-plate IEDs.

In some cases, as our interviews revealed, Taleban fighters hid their use of pressure-plate IEDs from the leadership because of their sensitivity. For example, a Taleban source told the author that a commander had laid pressure-plate IEDs on both sides of the Paktika-Ghazni highway from 2018 onwards, without informing the leadership. The Taleban source said that in April 2021, a visiting Taleban delegation travelled along the road and heard about the use of pressure-plate IEDs. They warned him that planting such devices again could end his career in the Taleban.

Some of the variations in use were geographic. In the Nad Ali district of Helmand province, for instance, the vast majority of IEDs used, according to interviewees, were pressure-plate IEDs per the order of the district’s senior commander. (In 2017, according to UNAMA, half of the civilian fatalities from pressure-plate IEDs were in the southern three provinces of Helmand, Kandahar and Uruzgan.[12]) In other provinces of Afghanistan, such as Paktia and Ghazni, either their use was ceased, or local commanders took measures to save civilians from harm. It may be that in these areas, local communities were stronger and more organised vis-à-vis the insurgents and could mobilise to demand better protection.[13]

Also possibly contributing to a change of tactics at this point in the conflict more generally was that, after the ISAF withdrawal and the decision by President Barak Obama not to target the Taleban, the insurgents went on the offensive, trying to capture more and more territory. When the ANSF began to re-take territory, Taleban tactics changed accordingly. In 2015, there was a decline in the civilian casualties caused by IEDs generally, but again an increase in those caused by pressure-plate IEDs, reported UNAMA, a further 35 per cent increase compared to the previous year (1,051 civilian casualties, 459 deaths and 592 injured).

The increase in civilian casualties from pressure-plate IEDs stems from the growing use of these devices by Anti-Government Elements as a defensive weapon to slow or prevent advancement of Afghan security forces before, during and after ground engagements. UNAMA documented multiple incidents of pressure-plate IED detonations in civilian agricultural areas, footpaths, public roads and other public areas frequented by civilians. These IEDs killed and maimed civilians as they went about their daily lives, traveling between villages and grazing livestock.

The final years of the Republic

UNAMA statistics show that 2012 was the peak year for civilian fatalities from IEDs, and after that, they declined until 2019 and 2020. In those two years, IEDs were the second most effective tactic used by the Taleban against the Afghan National Army (ANA) after direct fires (see page 19 of this 2020 US Department of Defence report to Congress). 2021 would have been the worst year for IED use and civilian casualties by a long way if the war had continued at the same intensity until December.

In those last years of the insurgency, IEDs again became a highly effective weapon against government forces, extremely intimidating for the ANA and resulted in some major defeats. Since the reinforcement of ANA bases in areas of conflict was mostly carried out by road, given the lack of sufficient air power, Taleban IEDs managed to cut off most of the reinforcement routes by lining roads with enormous IEDs. An ANA commander in Maidan Wardak province told AAN in early April 2021:

The Taleban’s mines block our reinforcement routes. Many of our bases and even district centres fall to them due to this blockage of reinforcements because with that you can’t fight for too long. Last week, a base fell to the Taleban in the Sheikhabad area after they blocked the road by planting mines. Reinforcements and ammunition did not reach [the base], and after one week under siege, they left the base with everything inside and retreated to our base in the night.

An ANA commander from Zabul described to the author in April 2021 interview what it was like facing IEDs:

Mines are the hidden enemy. You wouldn’t know [what has just happened], but you see the limbs of your friends in the air. In the war with the Taleban, mine detection and protecting your life from them is the most difficult task we deal with. It causes us to slow down our operation and at the same time, they [the Taleban] often attack us. Our mine detectors are also targeted by the Taleban snipers during detection operations, and that is a huge loss for us. I can say that if the Taleban didn’t use mines, they could be defeated in the war.

How to weigh up the Taleban’s use of pressure-plate IEDs?

The leadership did recognise that particular brutal or ‘unnecessary’ violence could alienate the population. Civilian interviewees, asked years later about the Taleban of the early insurgency, described a movement that became less brutal. They cited the insurgents stopping beheading people as a terror tactic, reducing the number of extra-judicial killings in their areas, and that they now placed IEDs more carefully. A resident of Sayedabad district in Wardak province, interviewed in March 2021, for example, referred to such changes in tactics and attitudes towards civilians and said the Taleban “were very brutal in their first years, but now they have become [more] human.” The leadership also sometimes removed or disarmed commanders if they had been particularly harsh, presumably because they caused a backlash. For example, in 2018, a notoriously ruthless commander in the Yahyakhel district of Paktika province was replaced because his extremely hard attitude toward people in his home district had prompted criticism of the movement as a whole. He was only moved sideways, appointed as the supervisor of the Taleban ‘hideouts’, the houses for injured fighters, madrasas and so on, in Peshawar, Pakistan.

Taleban leadership concerns over civilian harm from IEDs stemmed from the damage they were doing to the Taleban’s overall war effort and the movement’s reputation. Those concerns mirrored similar worries felt by the senior US military leadership over their forces killing and injuring large numbers of Afghan civilians in air strikes, search operations and escalation of force situations when, for example, civilians driving ‘too fast’ towards checkpoints were killed too swiftly. General Stanley McChrystal, commander of ISAF and US forces in Afghanistan, 2009-10, and his successors began to prioritise reducing civilian harm seriously. The number of civilians killed and injured by foreign forces fell dramatically as they put in place new rules of engagement, better investigation and reporting and pre-deployment training (see AAN reporting from 2012 and this 2016 report from Open Society Foundations).

There were many differences in Taleban efforts to reduce their use of pressure-plate IEDs. The Taleban senior leadership were aware of the need to keep rural communities onside and to present the Emirate as competent and fair, a government-in-waiting, both to international audiences and other Afghans. Yet, they were either unable to control Taleban fighters and commanders on the ground or greatly influence the military commission. Another contrast is the US impetus to reduce civilian harm which had come from the US military leadership. On the Taleban side, it had come from political figures, not those in charge of the war effort. US and other foreign soldiers did complain that the changed rules of engagement which gave far greater priority to the protection of civilians, inevitably led to greater risk to their lives. Nonetheless, they, largely obeyed orders. Moreover, unlike foreign armies, there was no single clear command about pressure-plate IEDs for the Taleban to obey; instead a continuing difference of opinion prevailed at the highest levels. A direct order from Mullah Omar would have carried more weight with the rank-and-file and their commanders, but it did not come. Perhaps he was not in a position to order it at a time when the debates over it erupted, given his deteriorating health around this time.

Taleban insurgents were always more sceptical of any restrictions on their room for manoeuvre and were far more autonomous. Fighting Taleban weighed military advantage and the risk to themselves of not using pressure-plate IEDs with the harm to their civilian compatriots and the need to keep civilians onside as part of the war effort. For the most part, they were not persuaded and continued to deploy pressure-plate IEDs, as they felt they were needed. As AAN reported:

It is also worth recalling that the number of civilians killed and injured by US forces remained high and increased every time the US decided to push for military advantage in the conflict and/or widened their rules on targeting (eg carrying out offensive as well as defensive air strikes) or ‘relaxed’ measures to protect civilians. In 2018, for example, the US air force released 70 per cent more weapons in air operations than in 2017 (7,362 compared to 4,36; itself a significant increase on the 1,337 weapons released in 2016), but caused more than double the number of civilian casualties. UNAMA says this followed additional deployments to Afghanistan at the end of 2017 and “a relaxation in the rules of engagement for United States forces in Afghanistan, which removed certain ‘proximity’ requirements for airstrikes.” It suggested, as well, that the US military was taking a more ‘robust’ line against insurgents using civilian homes as cover. If the rules brought in by McCrystal and his successors had been adhered to, the US air force would not have killed and injured so many Afghan civilians. Like the Taleban, then, there was always a weighing of concerns; battlefield contingencies could cancel out worries of the harm civilian deaths would do to the war effort.

Always, as well, whatever protections the Taleban might have given to civilian populations in their heartlands fell away when it came to the cities. Suicide bombers targeting urban centres rarely appeared to try to spare civilians. The justification, as seen when speaking to Taleban in private discussion, was that they viewed the capital’s population, for example, as default supporters of the US and its allies’ war against them. “Those living under the control of an apostate regime,” a Taleban-affiliated scholar from Ghazni told the author, “who don’t denounce its anti-Islamic policies and don’t support jihad also share [responsibility for] what the Americans and the government is doing.”

Edited by Kate Clark and Rachel Reid

[1] For example, there were 12 reported beheadings documented by UNAMA in 2014, 9 of which were attributed to the Taleban. See “Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2014,” page 56.

[2] See Thomas Ruttig’s 2012 report, “The Mulla Dadullah Front: A search for clues,” in which he notes concerns within the Taleban that the methods used by Dadullah (and his brother who took over his mantle) were ‘un-Islamic’, with many first-generation Taleban rejecting Dadullah’s methods.

[3] Brian Glynn Williams: “Suicide bombings in Afghanistan,” Islamic Affairs Analyst, September 2007, page 4.

[4] The first rule in the International Committee of the Red Cross’s database of customary International Humanitarian Law concerns this:

The parties to the conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants. Attacks may only be directed against combatants. Attacks must not be directed against civilians.

[5] Some anecdotal reports suggest that Taleban were assisted by al-Qaeda and other foreign groups providing training in IED-making, for example, this Taleban fighter interviewed by Newsweek:

The Arabs taught us how to make an IED by mixing nitrate fertilizer and diesel fuel, and how to pack plastic explosives and to connect them to detonators and remote-control devices like mobile phones. We learned how to do this blindfolded so we could safely plant IEDs in the dark.

See also “The Taliban at war: inside the Helmand insurgency, 2004–2012,” Theo Farrell and Antonio Giustozzi, page 845, and “The Battle for Afghanistan, Militancy and Conflict in Kandahar,” Anand Gopal, 2010, New America Foundation, page34.

[6] Out of the 21 interviews, seven were with Taleban fighters – three from Ghazni, four from Helmand, two from Maidan Wardak and two from Paktia – and nine with residents, a journalist and two former government soldiers from the same provinces. Three interviews were conducted via mobile phone and the rest face-to-face.

[7] UNAMA Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2010, page 2.

[8] Thomas H. Johnson & Matthew C. DuPee (2012) Analysing the new Taliban Code of Conduct (Layeha): an assessment of changing perspectives and strategies of the Afghan Taliban, Central Asian Survey, 31:1, 77-91, DOI: 10.1080/02634937.2012.647844 (see here).

[9] Statement of Taleban’s Leadership regarding the Inception of the Spring Operations, 30 April 2011, paragraph 4 (link is no longer working, but the statement was seen by the author).

[10] Giustozzi, Antonio, The Taliban at War: 2001-2018, Hurst & Company London, 2019, page 143.

[11] After 2014, the US alone among the foreign forces had a potential combat mission and their involvement in offensive operations, largely air or special forces on the ground, waxed and waned until their final departure in 2021.

[12] A Protect of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2017, page 32.

[13] Some local Taleban groups banned the pressure-plate IEDs locally, Giustozzi reported in “The Taleban at War, 2001-2018,” page 144.

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 20 Aug 2022

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign