Afghanistan Analysts Network

Chapter 2: The Transition to a new political order

Chapter 3: Human Rights

Chapter 4: Economic collapse and the struggle to find food

Chapter 5: Aid after the Taleban takeover

Chapter 1: US withdrawal, Republican Collapse, Taleban Victory

President Biden’s 14 April 2021 announcement of the full, rapid and unconditional withdrawal of international military forces from Afghanistan by 11 September gave the Taleban a timetable to launch their assaults on government-held areas. They pushed against Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) which had been hollowed out by corruption, churn in senior leadership and demoralisation, as soldiers and police realised that neither the US nor Kabul had their backs. In a matter of months, district after district and then provincial capitals fell until finally, the Taleban captured Kabul on 15 August. The Taleban’s rise to power: As the US prepared for peace, the Taleban prepared for war argues that America’s strategy of recent years has been one factor – although not the only one – facilitating the Taleban takeover.

One week after the fall of Kabul, Kate Clark looked at the flaws in US Special Representative for Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad’s strategy, driven as it was by the United States’ desire to withdraw its troops. He and President Trump had already given away the US’s main bargaining chip when they signed the US-Taleban Doha Agreement on 29 February 2020. They had agreed to an almost unconditional withdrawal in return for the haziest of commitments to ‘intra-Afghan talks’, an effective gamble that the Taleban actually wanted to negotiate an end to the conflict with Kabul, rather than try for military victory.

As it turned out, the Taleban were planning their final push to take Afghanistan, while the Afghan elite were blind to the wolf at the door. Even as the US was packing up to leave and the Taleban were preparing to fight for power, Afghanistan’s elites continued to fight over posts and milk the state. The government failed to prepare for a post-US Afghanistan or even believe the US would ever actually leave.

In the final days of the Republic, Afghanistan’s last president Ashraf Ghani had few allies and was isolated. His micro-managing, inability to delegate, quick temper and fear of rivals had left the administration drained of talent, flexibility and decisiveness. Inaction, such as the failure to properly resource those organising to resist, had further sabotaged the Republic’s defence. He appeared out of touch with reality; as the Taleban marched towards Kabul, the Palace continued business as usual. On 12 August, three days before he was to flee Afghanistan, Ghani was busy meeting the country’s Olympics team and attending international youth day celebrations. His secret flight out of Afghanistan as the Taleban entered Kabul, without informing even the defence minister, and leaving no transitional arrangements in place, will be a lasting ignominy.

In the end, the fall of the Republic was more rapid than anyone had imagined and came well before the 11 September 2021 deadline set by President Biden. By fastening America’s departure from Afghanistan to the twentieth anniversary of the al-Qaeda’s 2001 attacks on the United States – the event that brought the American military to Afghanistan – President Biden ensured that the day will be celebrated by the Taleban and the various violent jihadist groups around the world as the second defeat of a superpower by Afghan mujahedin and remembered by history as the start of the Taleban’s second Emirate.

The beginning of the end

In the weeks following President Biden’s announcement, a thunderstruck Afghanistan struggled to come to terms with the implications of its looming abandonment. In his report Preparing for a Post Departure Afghanistan, Ali Yawar Adili looked at how the Ghani government tried to put a brave face on the situation, even as it failed to gain consensus within its own ranks on what to do. Western diplomats and Afghans with means ‘rushed to the door’, while former factional commanders and leaders talked of mobilising a ‘second resistance’ outside the government’s formal military structures – a repeat of what they had done 20 years earlier as the anti-Taleban Northern Alliance. The announcement of unconditional troop withdrawal transformed the Taleban’s approach to the intra-Afghan talks, fatally weakening any chance of a negotiated end to the war.

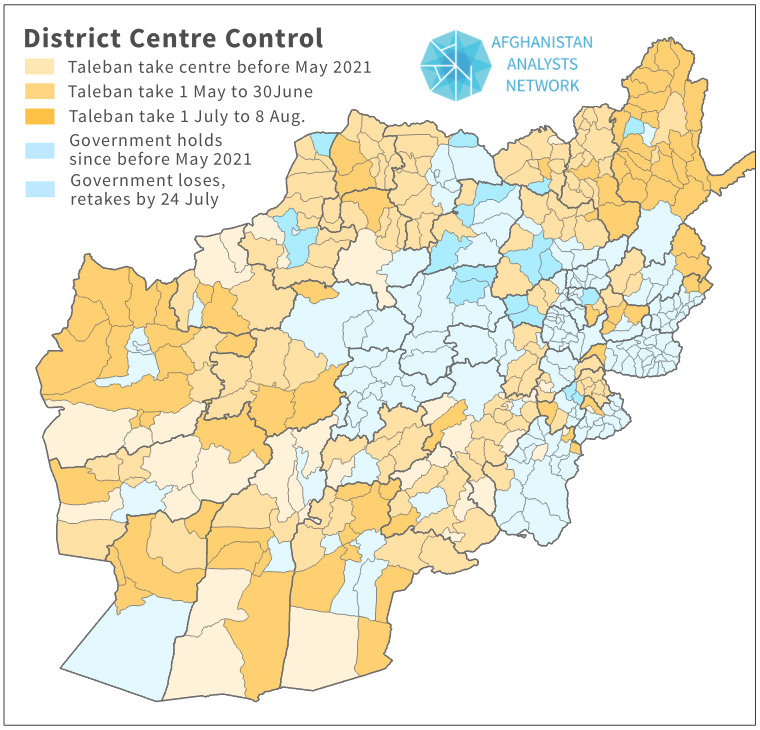

It was not long before the Taleban started their push to capture territory in earnest. They kept to their agreement with the US not to attack the departing international forces, but no longer saw any benefit to be gained by restraint against Afghan forces. Following the 2020 US-Taleban agreement, they had already intensified their attacks on their fellow Afghans, but now the gloves were off. In A Quarter of Afghanistan’s Districts Fall to the Taleban amid Calls for a ‘Second Resistance’, Kate Clark and Obaid Ali charted the fall of some 127 district centres out of a total of 421 to the Taleban between 1 May to 29 June. The maps below by Roger Helms illustrate the Taleban’s mounting territorial gains, showing how the balance of power shifted steadily and then ineluctably in the insurgents’ favour.

That shift of power was felt at first particularly in the north, which after bloody battles and ultimate defeat in a few key districts, saw a collapse of the ANSF and the civilian authorities at breakneck speed. More than 60 districts in nine provinces (Faryab, Jawzjan, Sar-e Pul, Balkh, Samangan, Baghlan, Kunduz, Takhar and Badakhshan) had been overrun or ceded to the Taleban by 29 June, most of them in the last ten days of the month.

When the Taleban were last in power in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it had been the north where they faced their most resistance, so beginning their push for power in this region now looked like a pre-emptive strike to prevent any new northern opposition from organising. As much as Taleban strength of canniness led to their trouncing the ANSF, equally significant was corruption in government, especially in the all-crucial security ministries and forces; questionable senior level appointment-making and persistent scarcities in supplies and salary payments also helped precipitate the collapse. Running out of ammunition or food had demoralised troops, already reeling from the US decision to withdraw.

By mid-July, the insurgents had gained control of almost 200 district centres, or just under half of the total.

Kate Clark’s Menace, Negotiation, Attack: The Taleban take more District Centres across Afghanistan looked at the Taleban’s strategy of focusing on border crossings and other money-making locations while avoiding a move on provincial capitals and eastern areas which border Pakistan. Many of the first districts to fall had been dismissed as ‘low-hanging fruit’, places where the government and ANSF had only controlled the district centre, often precariously so, but by mid-July, Taleban gains had gone well beyond the capture of those centres. As districts toppled like dominoes, ANSF morale plummeted further, as did the confidence of civilians in the government. The Taleban’s narrative that it was heading to victory proved more powerful than the government’s insistence that it was in control and could protect the people.

The Taleban’s push to sue for power exacted a heavy toll on civilians in Afghanistan. Kate Clark took a deep dive into UNAMA’s mid-year report on civilian casualties, published on 26 July. New UNAMA Civilian Casualties report: The human cost of the Taleban push to take territory examined numbers of civilians killed and injured in the first six months of 2021 which were back up to the record highs of 2014 to 2018. UNAMA also reported on the deliberate destruction and looting of civilian homes, schools and clinics in newly-captured territory, the vast majority by or with the complicity of Taleban fighters.

As Afghanistan entered the second half of 2021, fears over the harm done by this bitter conflict were legion, of further loss of life and the destruction of homes, of having to flee through areas planted with IEDs, of being subject to abuse or ‘revenge’ attacks by armed men and of the denial of dignity and respect. The cut-off point for data for the UNAMA report had been 30 June. By the time it was published, on 26 July, the conflict had raged on, more districts had fallen to the Taleban and the toll on the civilian population had mounted. We calculated that at least 226 of Afghanistan’s 421 district centres, or more than half, had by then fallen to the Taleban.

As well as looking at the national picture, AAN wanted to publish several case studies of how particular districts or provinces fell – the local politics, local economics, the deals done, the role of elders and how government forces had fared.

The first to be published was on Laghman province, which sits on the main highway between Kabul and the Torkham border crossing with Pakistan; focusing on it was consistent with the Taleban’s strategy of seeking to deny the government access to domestic revenues. At that time, in early August, Laghman, long-contested, had seen four of its six districts fall to the Taleban between late May and mid-July. Yet the government still had a precarious hold on the provincial capital Mehtarlam. Ali Mohammad Sabawoon’s Taleban Victory or Government Failure? A security update on Laghman province took a close look at how political rivalries, the competing demands of local elites and a failure to establish a united front with strong command-and-control had contributed to the Taleban’s success in this strategically important province. He looked at how three district centres and multiple security outposts had fallen to the Taleban without bloodshed, following mediation by local tribal elders and the surrender of government forces. The government arrested the civilian and military leaders implicated in these surrenders, but it was not enough to stem the political turmoil that had seen the province cycle through three governors in under a year.

In The Domino Effect in Paktia and the Fall of Zurmat: A case study of the Taleban surrounding Afghan cities,Thomas Ruttig and Sayed Asadullah documented the successive collapse of 11 of Paktia’s 14 districts to the Taleban in six days, in late June/early July, culminating in the fall of the politically significant Zurmat district on 2 July 2021. They reconstructed how these districts, protected by a 1,000-strong government force, had fallen so rapidly to just 200 to 300 Taleban fighters on motorbikes. Strategy and morale, it seemed, had trumped numbers. They explored the Taleban strategy, government weakness, the shifting loyalties of local people, the role of tribal elders and the history of violence in Zurmat – all contributing to the Taleban capturing Zurmat, which put the insurgents at the gates of the provincial capital, Gardez.

On 6 August 2021, the Taleban gained control of their first provincial capital, Zaranj in Nimruz province. As Taleban fighters entered the city, government security forces melted away, many to Iran through the nearby border. They left the provincial capital free for the taking. Fabrizio Foschini’s The Fall of Nimruz: A symbolic or economic game-changer? argued that after an unexpected and highly successful sweep of rural districts in Nimruz, the Taleban had encountered significant resistance when they turned their sights on major cities, such as Kandahar, Herat, Ghazni and Lashkargah. In order to boost the morale of their fighters, who had grown accustomed to routing the ANSF, Taleban military leaders changed tack; while keeping up the pressure on those cities, they also started targeting relatively undefended provincial capitals like Zaranj.

At first glance, this province in Afghanistan’s remote southwest might look inconsequential, but Nimruz is a leading import-export hub, ranking fourth for customs revenues, after Nangrahar, Herat and Balkh. It is also a gateway for the smuggling of illicit drugs and Afghans seeking to go to Iran and beyond. Capturing Nimruz was a morale boost to Taleban fighters, who went on to take four other provincial capitals in quick succession – Sheberghan in Jowzjan, Sar-e Pul, Kunduz and Taloqan in Takhar.

From before the fall of Kabul, the AAN team had been interviewing Afghans on how their district or city had fallen and what changes they had seen in their lives. Afghanistan’s Conflict in 2021 (1): The Taleban’s sweeping offensive as told by people on the ground was the result: a compilation of story fragments gathered by AAN researchers and compiled by Martine van Bijlert. These accounts reveal how variable takeovers had been – in the level of violence, the duration of the fighting or standoff, the pace of events, whether the ANSF had resisted, fled or surrendered, and the extent of suffering among civilians. Interviewees gave vivid descriptions of fierce fighting, particularly early on and around the cities, and of desperate attempts by individual ANSF units to hold on to their positions. Small pockets of besieged security forces left to fend for themselves often held off Taleban attacks for weeks. Such accounts explain the anger and confusion when people talk about the incompetency of the Kabul leadership, the absence of leadership and the lack of support. People described military units as being often unable, no longer willing or sometimes not even authorised to fight back against the Taleban onslaught.Things moved at breakneck speed after the fall of Zaranj. By the morning of 15 August, just nine days later, 19 more provincial capitals had fallen into Taleban hands and six of the seven zonal army corps had either surrendered or dissolved and the Taleban were on the outskirts of the capital. That morning, on what would turn out to be the final day of the Republic, we published Martine van Bijlert’s Is This How It Ends? With the Taleban closing in on Kabul, President Ghani faces tough decisions. It summed up what had driven the rapid fall of Afghanistan’s district and provincial capitals to the Taleban and described the government’s now tenuous prospects. Many, most notably the government itself and the US, which was still operating on the assumption that the Taleban would only begin their offensive on the capital in earnest after all the foreign troops had left on 31 August, were caught off-guard. Foreign governments were clamouring to evacuate their staff and nationals and the Afghan public was coming to terms with the fact that the Americans were leaving with scarcely any thought for what was left behind. A few hours later, Ghani fled Afghanistan in a helicopter for Uzbekistan, and eventually the United Arab Emirates, and the Taleban entered Kabul as conquerors. Kabul police and security forces melted away and, in the end, the Taleban entered Kabul without resistance. By nightfall, they had taken control of the Presidential Palace.

The fall of the Republic did not come out of the blue. If the government and the US had been unprepared, the Taleban were not. They seemed to have been planning what they would do when international forces left for months, making deals and issuing threats and using networks they had built over the years. In many ways, those final months were an acceleration of the existing state of affairs in large parts of the country: an ongoing war with deaths, revenge killings, aerial bombardments and an ever-encroaching Taleban.

During the Taleban offensive, they were winning the information war with a mass of social media accounts distributing a deluge of carefully curated images and videos of their fighters running through towns or taking control of government buildings and the Taleban flag raised in various locations or, two days before the fall of Kabul, footage of a slightly dazed Ismael Khan, former governor of Herat and mujahedin strongman, was distributed on social media after being detained by Taleban forces as he attempted to cross the border into Iran. In the last days of Kabul under the Republic, cries of ‘Allah-u Akbar!’ had been shouted out across the night-time city, a symbol of opposition to the incoming Taleban. Yet, the Palace had continued to live in its own surreal bubble, including now pointless donor-driven ceremonies and meetings and even a bizarre visit by Ghani to the ancient Bala Hissar fortress in Kabul. Terrified Afghans had been arriving to what they thought would be the safety of the capital in their numbers, and a humanitarian crisis was starting to unfold. Ghani’s now infamous 14 August video message to the nation made vague commitments to remobilise the forces, conduct wide consultations, and work to end further violence, but the subtext was clear – the fight was over.

Chapter 2: The transition to a new political order

The end, when it came, brought to the foreground the apprehensions of an anxious nation wondering what this turn of events would mean to their lives. Some Afghans headed to the airport seeking to flee and find refuge outside Afghanistan. Many more stayed home to wait for the start of a new chapter in Afghanistan’s history to unfold and the streets were largely left empty. Martine van Bijlert contemplated the emergence of the Taleban as Afghanistan’s new leaders in Afghanistan Has a New Government: The country wonders what the new normal will look like.

On reaching the Arg, the Taleban had reportedly declared that they had no interest in a shared interim government and were simply going to rule by themselves. And so it was that on Monday 16 August 2021, the Taleban started their transition from a warring group that used, among other things, terror to achieve its goals to a government that would be held to account and faced a plurality of opinions, politics and lifestyles. How would they negotiate the demands of a generation of Afghans unaccustomed to Taleban rule and, in particular, the demands of Afghan women for their share in public life? The real litmus test, van Bijlert wrote, was girls’ education. Would Afghan girls be allowed to attend school and university and, if so, under what conditions?

Taleban’s spokesman Zabihullah Mujahed held his first press conference with an announcement, among other things, of a general security guarantee (often referred to as an amnesty) for those who had worked with the Republic. He said there would be no reprisals. As we saw in Martine van Bijlert’s The Taleban leadership converges on Kabul as remnants of the republic reposition themselves, there was a great deal of uncertainty about the Taleban’s emerging strategy and the shifting alliances of Afghanistan’s old political elite: Would Taleban leaders engage with the various powerbrokers, such as former president Hamid Karzai and former chief executive Abdullah Abdullah, who had not fled and who were trying to mediate on behalf of the remnants of the Republic?

Outside Kabul, there were reports of skirmishes and protests, and also pockets of resistance by those still holding out against Taleban rule. In Panjshir, First Vice-President Amrullah Saleh and Ahmad Massud, the son of Ahmad Shah Massud, were said to be organising a resistance.

Meanwhile, the scramble to leave the country escalated, with Taleban fighters manning checkpoints outside the airport, often violently. The evacuations focused mainly on foreign nationals and employees, leaving many Afghans desperate to get to safe harbours rushing to the airport and risking life and limb to secure a much-coveted seat on one of the evacuation flights.

Two weeks after the Taleban takeover, the US announced that the withdrawal of its forces from Afghanistan was complete. The Taleban declared a “historic victory,” celebrated the defeat of America and the re-emergence of Afghanistan as a “free and sovereign” nation, while the Afghan public wondered what their country would look like and how it would be ruled. In The Moment in Between: After the Americans, before the new regime, Martine van Bijlert looked at how the Taleban continued to project an image of a government girding itself up to rule. Already, there were signs of power struggles between different Taleban leaders, Ghilzai and Durrani, eastern and southern networks, and hardliners and those looking for more flexibility. The Taleban were also grappling with a pressing problem – how to disarm the thousands of Taleban fighters who, in the absence of as yet codified rules and procedures, were policing the population of Kabul and other cities and towns, deciding themselves what was inappropriate behaviour, hairstyle and dress.

There were reports that they had beaten up, arrested and shot men and boys for flying the Republic’s flag and more worrying reports of reprisals against the proponents of the fallen Republic. In addition, on 26 August, ISKP (the Islamic State Khorasan Province) had killed at least 170 Afghans and 13 US troops in a suicide attack at Kabul airport. The violence was not over.

At year’s end, Kate Clark looked at the historical parallels and differences in the fall of the Republic and the coming to power of the Taleban’s second Emirate with earlier regime changes in Afghanistan’s conflict in 2021 (2): Republic collapse and Taleban victory in the long-view of history. It was an attempt to assess the strength of the new Taleban polity and the dangers it faced as it sought to secure its rule over Afghanistan. So much of what marked 2021 out – the swift toppling of the old regime, the hubris of the victors, their disdain for former opponents, or even murderous intent, and a refusal to hear dissenting voices – had been seen before and with disastrous consequences.

The Taleban face a very different Afghanistan than when they were last in power. Afghans are more urban, more educated and more connected through social media and mobile phones to each other and to the world. A majority of children, boys and girls, have grown up going to school, and far more women have enjoyed paid work and a public voice. Now, the Taleban were no longer an insurgent movement, Clark concluded, they might find that the business of ruling Afghanistan, of providing public services and keeping public discontent at bay, is far trickier than when they were last in power.

The Second Islamic Emirate

As Afghans grappled with what the start of this new chapter meant for them, the Taleban pressed forward with solidifying their rule and re-establishing their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. They announced a caretaker government on 7 September, less than a month after they took control of Afghanistan. The 33-member cabinet was all-male, almost all-Pashtun, almost all clerical and all-Taleban.

Our report, The Focus of the Taleban’s New Government: Internal cohesion, external dominance, looked at the makeup of the new cabinet and what it signalled to other Afghans and to the outside world. Martine van Bijlert argued that the appointment of a ‘victors’ cabinet’ is not unusual after a change of regime. The 2001 cabinet was also heavy with the members of the armed factions that had opposed the Taleban, but there was a far greater ethnic diversity and two women. The Taleban cabinet, by contrast, is homogenous and dominated by southern Pashtuns. It has shown how the movement’s priorities coalesced around internal cohesion, monopolisation of power, the silencing of open dissent and dividing up the ‘spoils of war’, in terms of government posts, among themselves. The Taleban had seen no reason to compromise with anyone but their own.

Martine van Bijlert continued to look at the subsequent two rounds of appointments in The Taleban’s Caretaker Cabinet and other Senior Appointments. These appointments had solved only the immediate question of who would head the ministries and other state institutions that would help restart government. But there were still outstanding questions: How might the lack of experience by most of the new appointees in their respective portfolios affect the ability of the Taleban to govern a state whose economy and state institutions had collapsed? And how did the new government intend to fund itself, given almost all foreign aid stopped when the Taleban took the country by force?

As when they were first in power, in 1996-2001, ‘promoting virtue and preventing vice’ has emerged as a top priority for the new Taleban administration. Many Afghans feared the return of the Taleban’s ‘religious police’ and the notorious brutalities of the 1990s’ Amr bil-Maruf (virtue and vice) ministry. AAN guest author Sabawoon Samim compared Amr bil-Maruf in the two Taleban administrations, twenty years apart, in his report Policing Public Morality: Debates on promoting virtue and preventing vice in the Taleban’s second Emirate and argued that two decades on, Taleban views on the promotion of virtue and prevention of vice had evolved, but so had Afghan society. While all Taleban appear to believe it is a state’s duty to actively police public morality, Samim traced the emergence of a new generation of Taleban leaders, some of whom are less conservative, and asked whether they might take a softer approach.

Chapter 3: Human rights

Since the takeover, reports of human rights violations by the Islamic Emirate have been legion, but human rights abuses in Afghanistan did not begin on 15 August 2021. A little more than a week into the Taleban’s new regime, the UN Human Rights Council held a Special Session to discuss the human rights situation in Afghanistan – past and present.

Rachel Reid and Ehsan Qaane provided background to the UN session in UN Human Rights Council to talk about Afghanistan: Why so little appetite for action?, which the Ghani government, no doubt wary of additional accountability mechanisms that might implicate its own forces, had finally agreed to in early August 2021. Well before the Taleban takeover, pressure had been increasing for a stronger response by the UN to an escalation of human rights and conflict-related abuses in Afghanistan, especially since the massacre of schoolgirls at the Sayed ul-Shuhada school on 8 May 2021 in west Kabul. However, the resolution the council considered had been drafted by Pakistan, the Taleban’s main international backer. Far from creating a Fact-Finding Mission or Commission of Inquiry that would have had robust, long-term powers to monitor and investigate grave human rights violations, the resolution merely proposed that the High Commissioner report back to the Human Rights Council in nine months’ time, in March 2022. In the end, the Human Rights Council passed the resolution with just one revision: it asked the High Commissioner to give them an oral report in September, rather than wait for March 2022, giving rise to the question: Why, in the middle of a human rights crisis, did the United Nation’s leading human rights body signal to the world that the Taleban’s seizure of power should be met by nothing more than ‘business as usual’?

Kate Clark had taken a first look at civilian casualties in the Taleban’s military push for victory and accusations of Taleban revenge attacks in her already mentioned review of the takeover, ‘Afghanistan’s conflict in 2021 (2). UNAMA’s first major report on human rights in Afghanistan since the Taleban came to power on 15 August 2021 covered these and many more abuses, including arbitrary detention and the loss of the rights of women and girls. In Arbitrary Power and a Loss of Fundamental Freedoms: A look at UNAMA’s first major human rights report since the Taleban takeover, Kate Clark reviewed that report and found a recurring theme – the arbitrary way the new administration often works and the unpredictability of its laws, punishments and procedures. Her report examined what has facilitated these violations of Afghans’ rights: the clamping down on human rights defenders and the media, the suppression of free speech and peaceful protest and changes in state institutions, which all help to make the deployment of arbitrary and unaccountable state power so much easier.

Attacks on Hazaras/Shia Muslims

West Kabul, like many other places where Hazaras/Shia Muslims are in the majority, has been the target of some of the deadliest attacks in Afghanistan, especially since 2016. Attacks which, moreover, aim to kill the softest of targets – children, women in labour and with their newborns, sportspeople and worshippers. While the former government promised to step up measures to protect this community, including a much-touted security plan for west Kabul, it failed to deliver. Immediately after the Taleban took power in August 2021, the neighbourhood experienced a short-lived respite from attacks, but has since become the scene of a new cycle of assassinations and bombings.

In January 2022, Ali Yawar Adili looked at the post-Republic attacks in Dasht-e Barchi and argued that the failures of successive governments to protect ethnic Hazaras and other Shia-Muslims have left them exposed to violence, bloodshed and fear. His report A Community Under Attack: How successive governments failed west Kabul and the Hazaras who live there provides an overview of the widespread and systematic attacks against the community. In the face of ongoing attacks, the beleaguered residents of west Kabul have little hope that the country’s new rulers will take any more steps to protect them than the old ones did.

The rights of women and girls

Our last special report before 15 August 2021 felt, in retrospect, very important. We wanted to find out what women living in rural areas thought about war and peace. Given they are probably the most under-represented voices in the country and that women’s rights activists living in the cities were often dismissed and accused of misrepresenting their rural sisters who were assumed to be generally content with more conservative mores.

Through in-depth interviews with a wide range of women in rural Afghanistan, we gained rare insight into their views and experiences, fears about war and hopes for peace. Our special report Between Hope and Fear: Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war by Martine van Bijlert is an intimate snapshot of the pressures they were navigating, heartbreaking losses and, for most, the daily grind of living through a war while still, stubbornly, holding onto hopes for a peaceful future. In the end, our conversations revealed that the priorities of rural women were not that different from those put forward by the more well-connected women activists. They challenged the idea that women in rural areas are satisfied by what is often portrayed as ‘normal’ by the Taleban and other Afghan conservatives.

Since the Taleban took power, Afghan women have been stripped of many of their rights. Women workers have, largely, been sent home from government offices. They are hindered from travelling and suffer an enforced a strict dress code. Oder girls have been banned from school. Public protest dwindled in the face of the new authorities’ crackdown on those they viewed as dissidents and rebels. Women’s rights activists have proven the bravest of all, but the Taleban’s response has been harsh – detaining and, reportedly, beating women protesters who had taken to the streets to demand their rights. In the face of opposition, including even some reservations within their own ranks, the Emirate has appeared determined to disappear women from public life.

In May 2022, the Taleban announced a new order imposing what they called ‘sharia hijab’ with faces to be covered and women to only leave their homes if there is a real need; it tasked their male relatives with policing them. In We need to breathe too”: Women across Afghanistan navigate the Taleban’s hijab ruling, Kate Clark and Sayeda Rahimi heard from women across Afghanistan about what the ruling meant for them and how they and their families had responded. The authors argued that dress codes might seem less consequential than other curbs on women’s freedoms, but the order was symbolic of the Emirate’s desire to turn Afghan women into entirely invisible, private citizens again.

Girls’ education

Taleban policy towards women and girls, and especially towards girls’ schools, has always been one of the prisms through which the movement has been studied – and judged – since they first came to power in the mid-nineties. One of the first things the Taleban did after they took control of Afghanistan was to close girls’ high schools. All eyes, then, were on Nawruz, the spring equinox and the start of the new school year in most provinces, with the question of whether the Taleban would allow all the nation’s schools to reopen, as they had promised.

In a series of reports in the months leading up to Nawruz, the AAN team looked at Taleban practice and policy on schooling, especially for girls. The first piece drew on research from our ‘Living under the new Taleban government’ series. Kate Clark provided a clearer picture of where Afghan children were managing to go to school, and where they are not in Who Gets to Go to School? (1): What people told us about education since the Taleban took over.

The second report in the series, Who Gets to Go to School? (2) The Taleban and education through time traced the evolution of Taleban thinking on education historically to answer the question of why the Taleban are so uneasy about girls going to school when as mullahs, they should know the value Islam places on education and literacy. Authors Kate Clark and Reza Kazemi argued that many Taleban, coming from the rural south where women generally live in purdah, feel it is wrong for girls, especially those of marriageable age, to be outside the home. Yet, their discomfort stands at odds with the attitudes of many, if not most of their compatriots. There has been a sea-change in Afghan attitudes towards school education over the last 40 years: where there have been schools, Afghan parents, in very high numbers, have been choosing to send their children, including their older girls, to get an education. Going to school has become a normal part of most Afghan children’s lives since 2001.

In the third part in this series, Who Gets to Go to School? (3): Are Taleban attitudes starting to change from within?, guest author Sabawoon Samim looked at views of girls’ education within the Taleban movement, uncovering a relatively new trend, that some Taleban are now seeking out school and even university education for their sons and their daughters. He looked at how and why a significant membership of a group that banned girls’ education when it was last in power has changed their attitude towards schooling.

On the first day of the new school year, 23 March, the Ministry of Education’s preparations to open all schools were abruptly overturned by a last-minute decision from Kandahar to keep the ban on girls’ secondary schools in place. Months of promises that they would reopen left girls, parents and teachers alike distressed. The decision had profound ramifications for aid flows to Afghanistan, for the prospects of international recognition which the Taleban aspire to, and has led international interlocuters to rethink their policies on engaging with the Emirate.

Initially, the Taleban’s justification was confused, with various officials giving different reasons for the closure, from lack of teachers to inappropriate school uniforms. Eventually, a formal announcement cited the need for a “comprehensive plan, in accordance with sharia and Afghan culture.” In The Ban on Older Girls’ Education: Taleban conservatives ascendant and a leadership in disarray, guest author Ashley Jackson pieced together what had happened behind the scenes that led to this policy reversal. From interviews with local sources, including within and those close to the Taleban, aid workers, donors and diplomats, she found that Taleban power politics lay at the heart of the u-turn.

Girls’ education remains a sensitive issue with political repercussions. It is a key demand of the Western nations that are still not only Afghanistan’s main donors, but also key players in deciding to waive or maintain sanctions, both in Washington DC and at the UN Security Council. A far more important constituency, however, are the many Afghan parents who want their children, boys and girls of all ages, to be educated.

Freedom of speech/expression, civic rights

In Music Censorship in 2021: The silencing of a nation and its cultural identity, Fabrizio Foschini traces the threats and intimidation faced by musicians since the Taleban takeover. He explores how Afghan music had flourished over the previous two decades, and how it has contributed to the burgeoning of a national identity which recognises and enjoys Afghanistan’s diverse cultural traditions. Music in Afghanistan, he argued, has a unique potential for countering communal and ethnic rifts, rifts that the Taleban themselves denounce and claim to oppose.

The Taleban takeover of Afghanistan also delivered a devastating blow to one of the Republic’s few outstanding achievements – relatively good freedom of expression and a vibrant media sector. Since the fall of the Republic, nearly half of Afghanistan’s media outlets have closed and thousands of Afghan journalists and media workers have either left the country, lost their jobs, or are in hiding, with local media outlets and female journalists bearing the brunt of the downturn.

In Regime Change, Economic Decline and No Legal Protection: What has happened to the Afghan media?, Eshan Qaane attributed the media sector’s sudden and catastrophic decline to three principal reasons: the sudden shortage of financial resources, severe Taleban restrictions on press freedom, and a fear of violence. Access to information is now severely constrained in Afghanistan, and violence against journalists continues, with the Taleban identified as the main perpetrator. There are reports of journalists being told, formally and informally, what and how to report and women TV presenters are now compelled to cover their faces on air. In some cases, those who disobeyed have been summoned, interrogated, threatened, tortured and detained.

Chapter 4: Economic collapse and the struggle to find food

Even as the Taleban celebrated their unprecedented victory on 15 August 2021, Afghanistan had been transformed. It was suddenly poorer, more isolated and extremely economically fragile. The Taleban capture of power by military force had ruptured Afghanistan’s relationship with its donors, touching off a chain of events that triggered the collapse of an economy heavily reliant on foreign aid and already weakened by conflict, pandemic and drought.

Three weeks after the Taleban victory, Hannah Duncan and Kate Clark looked at the dynamics that had pushed the Afghan economy off a cliff – the turning off of the foreign aid tap, the empty treasury and frozen foreign reserves, the collapse of the banking system, the UN and US sanctions that had applied to the Taleban now applying to the whole country, and the flight of the country’s skilled workforce. In Afghanistan’s looming economic catastrophe: What next for the Taleban and the donors?, they argued that mitigating economic disaster would require revising existing sanctions regimes and continuing aid, but cautioned that negotiations between actors who have been hostile for years – the Taleban and the donor governments – would mean navigating a legal, practical and ethical minefield.

The collapse of the Republic had caught the country’s erstwhile backers unprepared and scrambling to devise new policies for engagement with the new Afghanistan. The victorious Taleban have demonstrated that they are in no mood to accept the concessions demanded by donors in exchange for funding, especially over the rights of women and girls.

Kate Clark continued her examination of the economic repercussions of the Taleban taking over a state dependent on funding from foreign donors hostile to them in Killing the Goose that Laid the Golden Egg: Afghanistan’s economic distress post-15 August. The report mapped out the decline of Afghanistan’s economy and the Taleban’s own economic fortunes since 15 August and looked at how, in the end, politics would decide whether the Taleban and Afghanistan’s donors could find ways – or not – to support Afghanistan’s ever-increasing poor.

Even what should have been a boon if no other existed, the end of the fighting, was wiped out by the grievous consequences of economic ruin: collapsing livestock prices, households selling their possessions, families taking children out of school to work or marrying very young daughters to men who would usually be considered unsuitable (too old, already married, or ‘strangers’) and parents of malnourished children unable to find a hospital or clinic still open. Typically, as is always the case, it has been women and girls who suffer disproportionately. When poverty strikes, they are often the last in the household to eat.

In the summer of 2021 AAN had started a new research project for ‘Living under the Taleban’ that looked into how life had changed in districts that were newly coming under Taleban control. The message from our interviewees was loud and clear: the new regime had brought many changes and much uncertainty, there was great disorientation, occasional nervous hope, but most of all, people were deeply worried about the economic collapse and the coming winter.

In the first instalment in a new series, Martine van Bijlert and the AAN team looked at how the sudden regime change had affected Afghan households. Living in a Collapsed Economy (1): A cook, a labourer, a migrant worker, a small trader and a factory owner tell us what their lives look like now provided a deeply human picture of how the economic downturn had affected the lives of Afghans as seen through the lens of a large urban middle class family, a landless labourer in a remote and poor area, a small trader with a garden, a factory owner and a former Gulf worker.

What was perhaps most striking from the conversations was the near complete lack of options, even for those who had been doing relatively well at some point in the past. The interviews presented a bleak blend of resilience, determination and depletion. People hoped to protect their children from harm and safeguard their future. They had aspirations for new ventures. They continued to look after others who were even worse off than themselves. And many of them were exhausted and stunned by the continuous onslaught of crisis and tragedy, every time disaster compounding disaster.

The series’ second report, Living in a Collapsed Economy (2): Even the people who still have money are struggling, mapped what the economic collapse has meant for the relatively fortunate – those who were wealthy to start with or had a diverse set of income streams, as well as those who still had a stable salary. We heard from a landlord and a relatively successful factory owner in Kabul, an NGO employee in Zabul, an extended family in Khost with a brother in Dubai, a former government employee in Badakhshan and the only ‘doctor’ in a remote area of Daikundi. It turned out that even these people were struggling. They too faced serious obstacles and setbacks and, in most cases, had to cut down on their expenses drastically. Most of them said they were no longer able to help others like they used to. Martine van Bijlert argued that the picture pointed to an unravelling of a critical part of Afghanistan’s social safety net – support provided by the relatively wealthy to others in need, within their families, neighbourhoods and communities – at a time when the country needed it most.

The series’ third instalment, Living in a Collapsed Economy (3): Surviving poverty, food insecurity and the harsh winter, provided a detailed and layered picture of the many ways Afghanistan’s economic collapse is affecting families and businesses. Martine van Bijlert and the AAN team returned to the people we had interviewed at the beginning of winter to find out how they had managed during the harsh winter months. For many, not much had changed, except that their situations had slowly worsened. Yet, despite the dispiriting hardship, most interviewees showed a remarkable determination to keep going and take care of their families and, often, their wider communities.

Van Bijlert wrote that the international focus on food aid for Afghanistan threatened to treat Afghans as a faceless and initiative-less mass, waiting to be helped. In reality, most households were doing everything they could to find marginal income and take care of each other. The problem was that the options are so very limited. Although most of our interviewees had received some form of food aid, which was much appreciated and provided a brief respite, the greater improvement in people’s lives would come only from access to income. The report underscored, once again, that Afghanistan needs more than humanitarian aid to restart its economy.

The change of regime was a moment of rupture, its aftermath the latest in a long series of upheavals that have marked the lives of most Afghans over the age of 55. For those living in rural areas, unpredictability stems not only from regime change and violent conflict, but also from drought, flooding and other natural disasters. Guest author, Adam Pain’s report, Living With Radical Uncertainty in Rural Afghanistan: The work of survival, helped deepen our understanding of how rural households attempt to survive and prosper in this ever-changing environment. He drew on lessons from a research project that traced the livelihood trajectories of rural households from 2002 to 2016. Given that rural households can rely neither on the state nor the market, he found they invested in village and household relationships. He asked whether this would be enough to get people through the latest economic shock. He also suggested a rethinking of the hitherto unsuccessful market-driven agricultural policy models for an Afghanistan that offers no long-term future opportunity for its rural households and no possibility of decent work in the urban areas domestically or regionally.

The state of the Agriculture sector

War, political upheavals and regime change are only part of the complicated dynamics that mar Afghanistan’s rural economy, but drought and regional politics also play a significant part in the fortunes of Afghan farmers.

In Crops not Watered, Fruit Rotting: Kandahar’s agriculture hit by war, drought and closed customs gates Ali Mohammad Sabawoon heard from farmers and others about the woes affecting the province, famous for its fruit production. While the end of the conflict should have meant better times for the farmers of Kandahar, as elsewhere in Afghanistan. Yet drought looked to be looming again and exporting produce has remained difficult and unreliable, with much of the fruit crop that was – or should be – destined for Pakistan and other markets further afield going to waste because of the frequent and unpredictable closure of crossings into Pakistan.

We also looked at two illicit crops, opium and cannabis, which are hugely important for the national and household economy. In March 2020, the Taleban banned the cultivation of cannabis and the production and trafficking of cannabis resin, known as hashish, in areas under their control. What now for the Taleban and Narcotics? A case study on cannabis looked at whether and how the ban was implemented using field research conducted by Fazal Muzhary before the Taleban captured power nationally. The report provided a useful context for considering future Taleban policy on this important sector of the illicit economy.

Then, seven and a half months after they took power in Afghanistan, at the beginning of the opium harvest, and at a time when Afghans across the country were suffering under the strain of economic collapse, the Taleban officially banned opium.

In The New Taleban’s Opium Ban: The same political strategy 20 years on?, Jelena Bjelica looked at the far-reaching and grievous consequences if the ban was implemented. Illegal opiates are among the few real export earners in a country where imports during the Republic had dwarfed licit exports, six to one. The illicit drug economy’s gross value in 2021, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), was estimated at between 9 and 14 per cent of the country’s GDP. Bjelica’s report probed the Taleban’s possible motives for banning opium and the similarities between this ban and the one the Taleban implemented in July 2000 when they were last in power. She argued that this ban, if implemented, would cause harm to many Afghans dependent on the illicit drugs industry, put even greater pressure on farmers and labourers already struggling to survive economically, and further dehumanise drug users put under compulsory and brutal treatments. Whether it even brings much goodwill from Afghanistan’s donors, she said, seemed doubtful; their concerns about Afghanistan’s opium cultivation are, for now, eclipsed by the Taleban’s ban on older girls going to school, their restrictive policies on women’s rights across the board and attacks on media freedom and the right to dissent.

Chapter 5: Aid after the Taleban takeover

With Afghanistan’s economy in freefall and a humanitarian catastrophe growing, donor nations came together at a virtual pledging summit, co-hosted by the United Kingdom, Germany, Qatar and the United Nations. The aim was to raise lifesaving humanitarian support for an unprecedented 22.1 million Afghans in need, as compared to 17.7 million in 2021. In A Pledging Conference for Afghanistan… But what about beyond the humanitarian? Roxanna Shapour and Kate Clark took a close look at the Humanitarian Response Plan – the UN’s largest appeal ever for a single country.

Donors were presumed to be on board with the Humanitarian Response Plan precisely because it was humanitarian, and therefore officially apolitical. Ultimately, however, the Taleban’s decision, made just before the conference began, to keep older girls out of school, derailed the funding drive and pledges came in at USD 2.4 billion, well short of the United Nations’ USD 4.4 billion target, although still sizeable.

A major focus of the international humanitarian response to Afghanistan’s economic collapse has been a ramped-up distribution of food aid, as large parts of the population no longer have the income to buy enough food for their families. Food Aid in a Collapsed Economy: Relief, tensions and allegations was the fourth instalment of our economic research based on interviews conducted across Afghanistan.

In this report, Martine van Bijlert and the AAN team looked at the reach, scope and implications of food aid distribution at the community and household levels and found that around half of the families we interviewed had, by mid-February, received some form of food assistance at least once. This was a testament to the determination and hard work of countless NGO employees, community members, government civil servants and UN staff, often under extremely difficult circumstances.

While our interviewees were grateful for the much-needed help and hoped it would continue, they also expressed recurring concerns that those who needed aid the most might not be receiving it. They described favouritism and interference in the selection of beneficiaries and, to a lesser extent, corruption and capture.

Most people reported that they and their communities were stretched far beyond their usual coping mechanisms. Many had depleted what reserves or options to borrow or sell they might have had. Food aid allowed them to feed their families, something at least, even if only for a short time, but Afghans desperately need their economy to restart, the government and its salaries to become dependable, and conditions for small businesses to improve.

However, while the Taleban continue to snub calls from Western capitals to respect human rights, including the rights of Afghan girls and women, and while they fear that funding will help strengthen the regime, donor countries have found it difficult to know what to do for the best to help Afghans.

In Donors’ Dilemma: How to provide aid to a country whose government you do not recognise, Roxanna Shapour looked at engagement between the donors and the Taleban, what the future of aid to Afghanistan might look like, how donors might reconcile their demands with the Taleban’s increasing restrictions on civic life, and what mechanisms exist that might allow for non-humanitarian assistance. She argued that what might at face value appear to be mixed messages from donors actually reveal real quandaries and complexities. While donors feel the need to respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and economic crises, they also want respect for human rights and security guarantees. The Taleban, for their part, are ambitious for international legitimacy, but have shown no inclination to concede anything to donors or, indeed, the demands of their own people.

Against this precarious backdrop, Western donors and diplomats have been left trying to answer tough policy questions and take difficult funding decisions. The strategy decided upon has been to funnel development and what has become known as ‘humanitarian plus’ aid largely via the World Bank’s multilateral trust fund to UN agencies and then to NGOs. The aim is to help Afghans and not help the Emirate, but the dangers are many – that the Taleban are inevitably strengthened as this policy frees up their own resources, that it creates parallel structures to government and is wasteful, with money going to headquarters costs and more expensive foreign and Afghan salaries.

Climate change

The change of regime has also affected the struggle to get money to help Afghanistan survive climate change. The Paris Climate Agreement recognises that the climate crisis has been caused by developed countries and requires them to compensate poor countries for the effects of climate change. Afghanistan, one of the lowest emitters of greenhouse gases but among the top ten countries most vulnerable to climate change, is suffering out of all proportion to the contribution they have made to damaging the planet’s atmosphere and climate.

In two reports, Global Warming and Afghanistan: Drought, hunger and thirst expected to worsen and The Climate Change Crisis in Afghanistan: The catastrophe worsens – what hope for action?, guest author Mohammad Assem Mayarlooked at how the climate catastrophe is already upon Afghanistan, evident in the increased frequency of droughts which cause hunger and distress and which are likely to become more frequent. He considered what the Republic did – or did not do – to reduce the harmful effects of global warming and finally discussed how climate change could be tackled under Taleban rule, now that Afghanistan is poorer, more isolated and cut off from global climate crisis funds aimed at helping poorer countries.

Out-Migration

Finally, AAN also looked at some of those trying to leave, focussing on the Afghans in Turkey. It has long been a destination itself and an important point along the transit route to Europe for Afghan migrants attempting to enter the European Union through its sea and land borders to Greece and Bulgaria. An increasing number of Afghans fleeing persecution or trying to find better economic opportunities have arrived in Turkey.

In the first instalment of a two-part report, Refugees or Ghosts? Afghans in Turkey face growing uncertainty Fabrizio Foschini looked at the worsening political and economic environment there, and at the bureaucratic hurdles that mean most Afghans in Turkey are undocumented. With its own unprecedented economic crisis, the climate has become increasingly hostile for Afghans.

Then, in Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: No good options for Afghans travelling to and from Turkey, Foschini explored how and where Afghans are living in Istanbul, their role in Turkey’s economy and how they are perceived in Turkish society. Through the voices of those interviewed, he looked at the difficulties of travelling to Turkey and when trying to move on, given that both Turkish security forces and those of neighbouring European Union countries have tightened their control of borders.

Conclusion

Like everyone else trying to report on what has been a momentous year for Afghanistan, AAN has had to struggle and persevere in trying to reflect the experiences of Afghans across the country, make sense of everything that has happened, and think about what this means for the future of the country and its people. We remain committed to producing analysis that is independent, of high quality and research-based and, as the second year of the Taleban’s second Emirate begins, of being bi-taraf but not bi-tafawut – impartial, but never indifferent.

AAN Dossier XXXI was compiled by Roxanna Shapour and edited by Kate Clark

All maps by Roger Helms

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 13 Aug 2022

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign