If implemented, this ban will have far-reaching consequences. The production of opiates – opium, morphine, and heroin – is “Afghanistan’s largest illicit economy activity,” according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The agency estimated that the gross value of the Afghan illicit opiate economy in 2021 was USD 1.8 to 2.7 billion: the total value of opiates, it said, “including domestic consumption and exports, stood at between 9 to 14 per cent of Afghanistan’s GDP, exceeding the value of its officially recorded licit exports of goods and services (estimated at 9 per cent of GDP in 2020)” (see here).

Afghanistan has already lost most of its other foreign income in the form of on and off-budget support, both civilian and military, since the Taleban captured power. Banning the cultivation of opium and export of opiates would be another grievous blow to the economy. The opiates industry ultimately provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of Afghans, as well as possible revenue still to the Taleban if they carry on taxing farmers and traders as they did when they were an insurgent group.[2] The opiates industry support the stability of the local currency, the afghani, and provides a much needed financial boost to the country as a whole. Opiates are among the few real export earners in a country where imports dwarf licit exports, six to one.

Globally, in 2020, Afghanistan contributed some 85 per cent of global opium production, supplying about 80 per cent of all opiate users in the world, UNODC reported in its 2021 Annual Opium Survey, so a ban fully implemented over the long-term would also have major consequences for the world.

Announcing the ban

The ban came as no surprise to this author. Many observers had been waiting to see whether the Taleban would follow up on a promise, given at a 17 August 2022 press conference – two days after they took power – by Taleban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahed, that “Afghanistan will be a narcotics-free country.”[3] He also asked donors to help with assistance for alternative crops. Also, given the Taleban are a movement of Islamic clerics, banning a narcotic crop should not be unexpected. See for example, the religious arguments and careful thinking they undertook before banning cannabis in areas under their control in March 2020. However, banning opium will hurt Afghans, including those living in areas which have often been more likely to support the Taleban. The domestic economic and political consequences of implementing this ban are potentially grave.

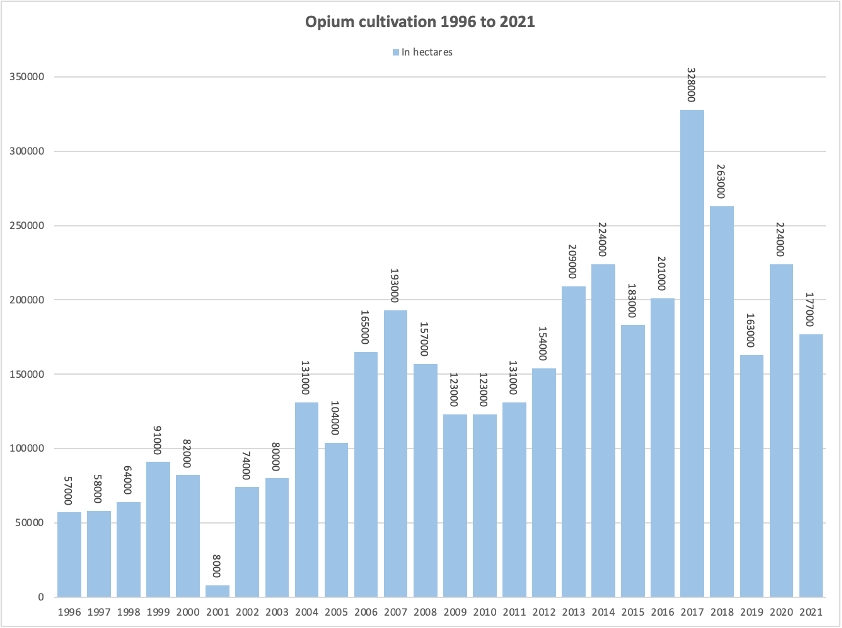

Despite Mujahed’s announcement of the imminent drug ban, Afghan opium farmers harvested and sold their opium crop undisturbed in 2021. Thanks to an increase in yield, the estimated 6,800 tons of opium harvested in 2021 was eight per cent more than 2020, even though less land had been sown with poppy – 177,000 hectares in 2021, down 47,000 from 2020, a decrease of 21 per cent, UNODC reported in its annual survey. “Production has exceeded 6,000 tons for an unprecedented fifth consecutive year,” UNODC said, adding that “this amount of opium could be converted into some 270 to 320 tons of pure heroin.”

The most significant change that came with the Taleban takeover was a hike in opium prices. Since 2018, the price of opium had remained relatively low, UNODC reported, because the international market for Afghan opiates had been “saturated, with little space to grow – unless more Afghan opiates are actively pushed into existing markets or new markets are established.” However, the hike in opium prices since mid-August 2021 was likely not a response to a change in the international opiates market, but a reaction to change of power in Kabul or what UNOC has described as a “perception of uncertainty.”

This price increase was an undisputed incentive for farmers to plant opium poppy again in the 2021/22 growing season,[4] as interviews with farmers from Kandahar, Herat, Farah, Laghman, Balkh conducted by AAN in late October 2021 showed. All mentioned the price hike and the Taleban’s silence on opium. In Kandahar, where prices for opium doubled and even tripled, a farmer from Kandahar explained the price rise: in 2020, he had got 30,000 to 35,000 Pakistani Rupees (USD 175 to 200) for 4.5 kilograms (equal to one man, an Afghan unit of weight) of raw opium; in 2021, he had got 60,000 to 100,000 Pakistani Rupees (USD 345 to 580) for the same amount. The farmer was also confident that he would be able to sow poppy again: “The Taleban have not announced a ban on the cultivation and trade of poppy so far, but the people know that they won’t forbid it, at least not this year.”

Some of our interviewees were cautious about their sowing choices for 2021/2022 and not only for fear of a Taleban ban, but also because of the general lack of water in the country caused by prolonged drought. Although the opium poppy is resilient and known for its drought-resistant qualities, ie it is a plant that does not need much water and can grow in desert-like conditions, this concern indicates just how scarce water had become. Still, most of the farmers we spoke to planned to sow their opium in autumn 2021.

Those farmers have now heard about the ban and may be relieved that it has, at least, come at the beginning of the harvest season (see footnote 3). This timing has lead to British expert on Afghanistan’s illicit drug economy, David Mansfield, among others, thinking this makes it “very unlikely [the ban] will be enforced this season” (see his Twitter thread on the ban here). It is likely only to be in the autumn, therefore, when farmers in poppy-growing areas are deciding what to sow that it will be clear how serious the Taleban are in enforcing this ban, and farmers in obeying it.

However, it is significant that the Taleban have chosen to ban this crop despite farmers already struggling to make ends meet, having been hit by drought, the damage wrought by conflict and the collapsed economy that followed their capture of power (and with it, the flight of most aid and military support and the newly-imposed UN and US sanctions on Afghanistan). This situation is remarkably similar to the first time the Taleban have banned opium when they were last in power.

The 2000 ban

The Taleban’s 2000 ban on opium was made in an edict by then leader Mullah Muhammad Omar on 27 July 2000. According to David Mansfield, it was the Taleban’s sixth attempt at banning opium. At the time, then head of UNODC research unit Sandeep Chawla praised the ban as “one of the most remarkable successes ever,” but later clarified that “in drug control terms it was an unprecedented success, but in humanitarian terms a major disaster” (see here).

At the time, the Taleban were under UN sanctions. UNSC Resolution 1267, passed in October 1999 (see this UN report), demanded that the Taleban turn over the head of al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, to a country where he had been indicted and that the Taleban cease providing “sanctuary and training for international terrorists and their organizations.” The resolution also cited the Taleban’s discriminatory policies against women and girls and Afghanistan’s production and trade in opium.[5] AAN co-director and then BBC correspondent, Kate Clark, said that it seemed that of the three issues the international powers were most insistent the Taleban address – bin Laden, women’s rights and opium – opium was the least difficult for the Taleban to take action on.

Mansfield thought the ban was driven by the Taleban’s desire for international recognition (it was only ever recognised as the legitimate Afghan government by three states, Pakistan, Saudi Arabic and the United Arab Emirates) and need for funds to assist a population affected by protracted droughts.[6] The lead economist responsible for the World Bank’s limited programme of work on Afghanistan at the time and subsequently the Bank’s country manager, Bill Byrd, writing in the 2004 World Bank report, Afghanistan’s Opium Drug Economy, attributed the ban to “a combination of [the Taleban] attempting to lever development assistance out of the international community, obtain official recognition as the government of Afghanistan from the UN, manipulate opium prices, and avoid international sanctions that were about to be imposed.” Many were sceptical that the ban would be enforced – a US government spokesperson said they doubted the Taleban had the “political will” to impose the ban – but as Clark and other observers found, the Taleban applied the ban vigorously; this was not just propaganda. It “was strictly enforced,” wrote Byrd, through a combination of religious messages, severe sanctions, threats, and promises that the international community would provide development assistance.”

The harm caused to Afghan farmers by the 2000 ban was profound. Those in debt found it difficult to survive the winter without the promise of an opium harvest and were forced to default or reschedule their seasonal loans.[7] Some had to resort to selling land and livestock and to even marrying off very young daughters to service their debt (see here). The opium ban was immensely unpopular in opium-growing areas and along with growing upset about the Taleban conscripting young men to fight their compatriots in the north, may have been a factor in the precipitous collapse of the regime the following year.

The ban’s success in terms of drugs control was also, ultimately, questioned. In January 2001, regional head of the previously-named UN Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention, Bernard Frahi, pointed to the huge stockpiles of opium inside Afghanistan. The ban on cultivation, he said, would only be felt once those stocks were exhausted, in three to five years, unless the Taleban destroyed the stocks. Speculation that the ban was actually intended to drive prices up was slammed by then Taleban Information Minister, Qudratullah Jamal, who told Clark the ban was there to stay. In the end, whether the ban would have lasted is debateable as the Taleban fell from power later that year. Their successor, the Islamic Republic, also ruled that opium was illicit, but was unable or unwilling to successfully eradicate it and replace it with alternative crops, meaning the Taleban ban on opium was effective for one harvest only.[8]

It is a fact that since the 2000 ban, opium cultivation has been on the rise in Afghanistan. According to the 2021 UNDOC report opium cultivation “has been increasing steadily over the past two decades, with an average rise of 4,000 hectares each year – albeit with strong yearly fluctuations.” After the 2001 slump, the area under opium cultivation in Afghanistan has also steadily increased compared to what it had been before the 2000 ban. In fact, it had doubled by 2007 and it increased almost fourfold by 2017 (see the table below).

The similarities between the situation in Afghanistan today and conditions back in 2000 are striking: severe drought, few or no countries recognising the Taleban government, sanctions, and a need for aid. The Taleban are again facing a demand to suppress opium production and export, but also the old demands as well: respect women’s rights and human rights, and stop supporting international jihadist organisations, al-Qaeda and others. The political risk for the Taleban of implementing the ban could also again be high, given that it would take away the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of people in rural areas. For farmers then as now, cultivating opium is a trusted option in uncertain times. It is relatively drought-resistant; relatively easy to sell – traders come to the farmer’s door; it preserves very well, so is useful as capital or savings and; it is an annual crop which does not need the investment of planting an orchard. (To see what farmers growing food crops in Kandahar, an opium-growing province, are up against, see our latest report on their struggles to survive.) Given that most opium fields require additional paid work force at time of harvest that is labour intensive, it is a crop that also benefits the rural landless and poor.[9] There are other differences, as well. Opium is far more extensively grown than it was in 2000 and any implementation of the ban would be much more widely felt. Whereas in 2000, the Taleban had come to power in many of the opium-growing areas with barely a fight, and only implemented the ban after having been stably in power for several years, this time, they have taken power after fierce and bloody battles; the conflict ended only recently and they have moved swiftly to announce the ban. The population is also greater than in 2000, so landholdings typically have to support more people (opium is, in general, an excellent crop for bringing income to families even on small landholdings). All this means that, although there are many parallels with 2000, the politics feel very different this time and the economics of households and the nation even more precarious.

The timing of the edict does mean that, unless the Taleban want to start destroying harvests and stockpiles, they have some time to consider or reconsider this ban. Indeed, Mansfield has suggested in the same Twitter thread, it may be an attempt to recast the political debate “to distract from the things the Taliban government doesn’t want to talk about – girls education & human rights”:

An effort to put pressure on the international community to respond to what will be portrayed as the Taliban’s act of ‘altruism’ – banning drugs used by others: a favour to the world. To press the donors for recognition, provide development assistance and lessen economic sanctions.

Such a tactic did not work for the first Islamic Emirate. Although the Taleban did get some narcotics funding, they also got additional sanctions. The first Emirate did secure USD 43 million in counternarcotics funding in 2000 thanks to the opium ban (see Mansfield, page 129), but it did not save the regime from further sanctions: the UN Security Council imposed additional measures (UNSC Resolution 1333) in December 2000 (see this New York Times report). In 2000/2001, the presence of al-Qaeda on Afghan soil was more important for the United States and other international actors than the opium harvest. In 2022, the banning of secondary school education for girls seems to be the totemic issue, embedded as it is in wider concerns about restrictions on women’s rights, the often violent curbs on a free media and on dissent and reprisal attacks on activists and former members of the security services. If the Taleban wanted to distract from the schools issue, the edict may fall flat. Moreover, especially given the Republic’s failure to curb opium cultivation, production and trafficking despite several billions of counter-narcotics aid dollars spent,[10] the issue may not even be one that donors want to dwell on. Moreover, the edict came less than a week after an international pledging conference in London raised USD 2.44 billion of a 4.4 billion UN appeal to help alleviate the dire humanitarian need in the country. As a tactic to persuade donors to give more money, it was strangely timed.

If the first Taleban ban taught us anything about their political rationale, as Mansfield rightly points out, both opium bans witnessed so far have been used as barging chips rather than well-thought-out policies. As was the case in 2000, this decree was introduced without apparent previous planning or long-term thinking. This is very different, it seems, from the internal decision-making taken by the Taleban as an insurgent group over banning cannabis in areas under their control in March 2010 when they took time to meticulously develop the religious arguments and careful thinking beforehand. Also noticeable, however, was that they only implemented the ban initially in some areas and not the major cannabis-growing provinces, as if in fear of a backlash farmers and traders. (See this AAN report on the Taleban 2020 cannabis ban).

The other side of the ban

The new edict also prohibits the use of drugs. There are between one and two million Afghans who regularly use alcohol and other drugs, including pharmaceuticals, for non-medical purposes, according to the two most recent national drug use surveys carried out in 2009 and 2015.[11] In recent years, the use of synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine has also increased. UNDOC 2020 data shows that in 2019 about 12 per cent of people aged 13 to 18 years of age (14 per cent of the boys and 8.5 per cent of the girls surveyed) reported using a substance, including alcohol, at least once in the past 12 months.

Shortly after the Taleban took power, they embarked on a campaign to round up drug users (see here and here). In Kabul, this meant raids on places where users gather such as the Pul-e Sukhta bridge in west Kabul (see this AAN report from 2015) The drugs users were taken to ill-equipped drugs treatment centres. In October 2021, the London-based daily The Independent reported the situation in one treatment centre:

The men are stripped and bathed. Their heads are shaved. Here, a 45-day treatment program begins…. They will undergo withdrawal with only some medical care to alleviate discomfort and pain.… The hospital lacks the alternative opioids, buprenorphine and methadone, typically used to treat heroin addiction.

The regime change also made it more difficult for drug users to find drugs, as one man in the Pul-e Sukhta area told AAN in October 2021: “I can’t buy any drugs. The Taleban treat us badly. They don’t let us sleep anywhere. They burn our tents and beat us.” He said the street price of drugs had also gone up since August:

I used to buy one small pack (about 6 grams) of opium, enough for two or three doses for 100 afghanis (about USD 1.30 based on the exchange rate before the takeover). Now, we buy it for 200 to 250 Afghanis (USD 2.27 to 2.80 based on the current exchange rate). A pack of chars (cannabis) used to cost 50 to 100 afghanis (USD 0.66 to 1.33). Now, it goes for 200 to 300 afghanis (USD 2.27 to 3.40). Everything is expensive now.”

An increase in the street price and scarcity of drugs was expected, given the increased risks to those selling it. However, it is noteworthy that this happened immediately after the Taleban takeover, before any ban on using drugs was officially announced. This suggests that the Taleban’s strict and vigorous enforcement of previous bans – when they were in power in the 1990s and those introduced in the areas under their control when they were an insurgent group – was vividly playing on people’s minds (see this AAN report on the Taleban 2020 cannabis ban).

It is self-evident that this edict, if implemented, will cause harm to many Afghans dependent on illicit drugs industry. It will put even greater pressure on farmers and labourers already struggling to survive economically, and further dehumanise drug users put under compulsory and brutal treatments. Whether it brings much goodwill from Afghanistan’s donors, however, seems doubtful; their concerns about Afghanistan’s opium cultivation is, for now, eclipsed by the Taleban’ ban on older girls going to school, their restrictive policies on women’s rights across the board and attacks on media freedom and the right to dissent.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour and Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | The full text of the Taleban leader Amir al-Mumenin Haibatullah Akhundzada’s decree prohibiting poppy cultivation in Afghanistan is available here. English translation from Al-Emarah website below:

As per the decree of the supreme leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), All Afghans are informed that from now on, the cultivation of poppies has been strictly prohibited across the country. If anyone violates the decree, the crop will be destroyed immediately and the violator will be treated according to the Sharia law. In addition, usage, transportation, trade, export and import of all types of narcotics such as alcohol, heroin, tablet K, hashish and etc., including drug manufacturing factories in Afghanistan are strictly banned. Enforcement of this decree is mandatory. The violator will be prosecuted and punished by the judiciary. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | As insurgents, the UNODC study estimated, the Taleban earned around 160 million USD from taxing opium cultivation, production and trafficking in 2016. This is equal to 5.4 percent of the total gross value of the Afghan opiate economy (3.02 billion USD in 2016). Overall, UNODC said that insurgents taxed an estimated 56 per cent of the opium harvest in 2016. In addition, over 100 million USD were collected from taxing manufacturing and trafficking. Similarly, the UN Security Council Sanctions Committee report estimated the overall annual income of the Taleban (drugs and other sources) in 2016 at around 400 million USD; half of which, it said, was likely to have been derived from the illicit narcotics economy (see this AAN report). |

| ↑3 | See the full transcript from the press conference here. Zabihullah Mujahed told the media on 17 August:

We are assuring our countrymen and women and the international community, we will not have produce any narcotics. In 2001, if you remember, we had brought narcotics content production to zero in 2001, but our country was unfortunately occupied by then and the way was paved for reproduction of narcotics even at the level of the government – everybody was involved. But from now on, nobody’s going to get involved, nobody can be involved in drug smuggling. Today, when we entered Kabul, we saw a large number of our youth who was sitting under the bridges or next to the walls and they were using narcotics. This was so unfortunate. I got saddened to see these young people without any faith in the future. From now on, Afghanistan will be a narcotics-free country but it needs international assistance. The international community should help us so that we can have alternative crops. We can provide alternative crops. Then, of course, very soon, we can bring it to an end. |

| ↑4 | The winter opium poppy is planted in October/November and harvested in April/May. The spring and summer seasons, mainly in the south, are short from April to July and July to September, respectively. |

| ↑5 | The resolution also cited the Taleban’s breaches of International Humanitarian Law and the capture by the Taleban of the Consulate-General of the Islamic Republic of Iran and murder of Iranian diplomats and a journalist in Mazar-e Sharif in 1998. |

| ↑6 | See David Mansfield, A State Built on Sand: How Opium Undermined Afghanistan. Oxford University Press, 2016. |

| ↑7 | From 1994 to 1999, farmers had an estimated average annual gross income of 1,500 US dollars per hectare; by 2000, their earnings had fallen to about 1,100 US dollars, close to what they would have made from cultivating legal crops which, at the time, amounted to around 900 US Dollars per hectare (see this 2002 UNODC study on the Afghan opium economy). In 2002, as a direct consequence of the Taleban 2000 opium ban, the average annual income for farmers rose to about 16,000 US dollars per hectare. The average plot in opium-growing areas was less than a third of a hectare in 2002, generating an annual income of about 4,000 US Dollars for a farmer at harvest and about 500 US dollars for a labourer. |

| ↑8 | Bill Byrd in the World Bank report cited above summed up its impact:

Although production slumped, the flow of opium out of Afghanistan did not diminish. Border and consumer prices remained high, while producer prices shot up…. The eradication campaign pauperized many farmers, and led to them incurring considerable debts which they are still repaying. The action effectively benefited the very interests that a war on drugs should first combat – the criminal trafficking interests (whose large holdings of opium inventories multiplied in value) and their political networks |

| ↑9 | Additionally, given that the new ban also prohibits “the usage, transportation, trade, export and import of all types of narcotics,” a significant number of Afghans working in the booming methamphetamine industry would also be left without a source of income. The decree does not mention methamphetamines by name, although it does cover “all types of narcotics such as alcohol, heroin, tablet K, hashish and etc., including drug manufacturing factories in Afghanistan.” The methamphetamine industry in Afghanistan has been expanding rapidly in Afghanistan since 2015, as this 2020 report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction found. This omission of methamphetamines by name could just be oversight or a function of the speed with which the edict was written, or the Taleban maybe unaware of the size and importance of the industry. |

| ↑10 | The US government alone from 2002 to2017 allocated approximately 8.62 billion US dollars for counternarcotics efforts in Afghanistan. “This included more than 7.28 billion US dollars for programs with a substantial counternarcotics focus and 1.34 billion US dollars on programs that included a counternarcotics component,” the report on counter-narcotics efforts in Afghanistan by the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction found. |

| ↑11 | UNODC attributes the use of drugs in Afghanistan in part to self-medication “for treatment of physical ailments (common cough, cold, acute and chronic pain, etc) as well as in case of psychological issues such as stress, anxiety, depression or trauma” due to a lack of access to adequate health care across the country. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign