The donors’ conference for Afghanistan began on Thursday, October 3rd, hosted by the United Nations in Dubai.

At this conference, both domestic and international organizations, along with political representatives from various countries, are discussing aid to Afghanistan, which is currently under Taliban control and facing a severe humanitarian crisis.

Participants discussed ways to provide aid to Afghanistan, exchanging views on the best approaches and reaffirming their commitment to continue offering humanitarian support to the people of Afghanistan.

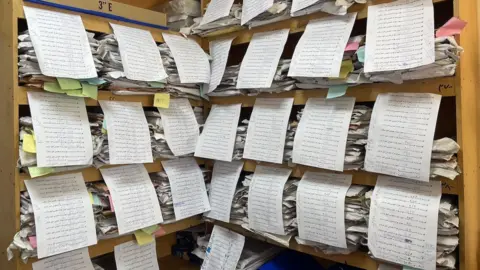

They reviewed monitoring mechanisms and emphasized the importance of transparency in delivering aid to ensure it reaches those in need.

Participants also expressed that Afghanistan remains at the center of the strategies of donor organizations and countries.

However, they stressed that “it is the responsibility of all stakeholders to create conditions where Afghans can sustain themselves through employment, rather than relying continuously on international aid.”

The conference also addressed the challenges posed by the Taliban’s new restrictions under the “Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice” law. This law has imposed severe limitations, particularly against women. Under this law, women cannot leave their homes without a male guardian, and their voices are considered indecent in public spaces.

According to a United Nations report, Afghanistan is facing one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. At least 23 million people in the country require humanitarian assistance. However, there are concerns about the reduction of these aid efforts.

Some countries and international organizations have also expressed concerns that the Taliban may misuse humanitarian aid for other purposes.

Karen Decker, the U.S. Chargé d’Affaires for Afghanistan, who attended the donors’ conference, told the media that since the fall of the Afghan Republic, the United States has provided $2.3 billion in humanitarian aid to Afghanistan.

Ms. Decker also mentioned that the results of the work conducted by two economic and narcotics groups from the “Doha 3” discussions would soon be reviewed by the United Nations, and the next major Doha meeting will also take place.

The donors’ conference highlights both the urgency and complexity of providing humanitarian aid to Afghanistan. While there is a commitment to helping millions of Afghans in need, concerns about transparency and the Taliban’s restrictions, especially on women’s rights, continue to challenge the international community’s efforts.

The call for a long-term solution emphasizes that Afghanistan’s future should not rely solely on aid. Sustainable employment and self-sufficiency must be at the core of any strategy to help the Afghanistan’s people build a better future.

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign