Afghanistan Analysts Network

Timeline of cuts in US aid under President Trump

20 January 2025 – President Donald Trump signs an executive order for all US-funded aid programmes to stop work, pending a 90-day review after which only programmes that make America safer, stronger or more prosperous will be retained.

28 January – Secretary of State Marco Rubio announces a temporary waiver for existing life-saving humanitarian assistance programmes.

10 March – Rubio announces that 83 per cent of programmes delivered by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) have been terminated.

24 March – USAID reports to Congress that it has terminated 4,443 awards globally and retained 898. Nine of these, worth USD 223 million, are in Afghanistan, meaning just under two-thirds of the USAID’s Afghan programme is intact.

8 April – The State Department announces that the US has cut all aid to the World Food Programme (WFP) in Afghanistan, amounting to USD 567 million; it transpires that this is not just WFP, funding but that the US has cut all humanitarian assistance.

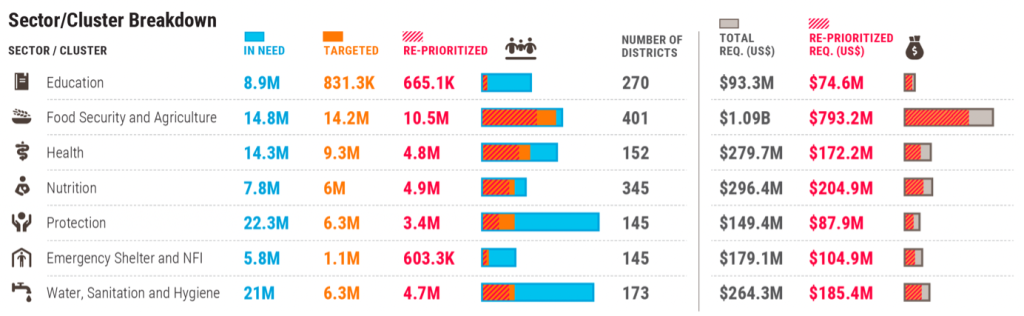

23 April – OCHA announces that it is reprioritising its 2025 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan in response to the cuts and will now be helping not 16.8 million Afghans, but 12.5 million.

30 April – SIGAR reports that all USAID programmes in Afghanistan, both humanitarian (USD 765 million) and for basic services (USD one billion) have been cut, with the exception of two small education programmes. It says the State Department has yet to give it a comprehensive list of cuts to its programmes. That information is still to come.

How US aid was cut

Any substantial cut to American aid to Afghanistan was going to hit the country hard because it has been such an outsized donor – providing more than 40 per cent of all aid in 2024. Already, when AAN first looked at the impact of President Trump’s ‘stop work’ order, on 10 February 2025, the signs were ominous that his hostility to USAID – he said it was run by “a bunch of radical lunatics” (NBC) – would have grave consequences for Afghanistan. Yet, there were also hopes that it would be spared the worst, either through a 90-day review of all programmes ordered by Trump or because of a waiver to “life-saving humanitarian activities” issued by Secretary of State Marco Rubio on 28 January, given that US aid to Afghanistan was already so strongly tilted toward humanitarian interventions.[1]

However, by 10 March, Rubio, who called the cuts to global USAID programmes an “overdue and historic reform,” tweeted that the administration had cancelled 83 per cent of USAID programmes, comprising 5,200 contracts on which the US had been spending “tens of billions of dollars in ways that did not serve (and in some cases even harmed), the core national interests of the United States.” Later that month, on 24 March, according to SIGAR’s second quarterly report this year, when USAID reported on its 90-day review to Congress, out of 5,341 awards valued at USD 75.9 billion, only 898 programmes remained active globally.[2] That included nine in Afghanistan.

Researchers Ian Mitchell and Sam Hughes, drawing on the list of terminated and still active programmes that USAID had given to Congress, calculated that the absolute reduction in funding for Afghanistan was USD 223 million,[3] making it the tenth largest decrease globally. At that time, the proportion of USAID contracts that had been terminated was comparatively low: 36 per cent of the USAID programme in Afghanistan had been cut, compared to 56 per cent in Bangladesh; 69 per cent in Tajikistan, 85 percent in Pakistan; 94 per cent India; and 100 per cent in Nepal and Sri Lanka. However, because Afghanistan has a relatively small economy and civilian aid/USAID has played a critical role, the researchers estimated that the hit to the economy, relative to national income, was the second greatest in the world, equivalent to 1.29 per cent of its Gross National Income (GNI) and surpassed only by Liberia (2.59 per cent).[4]

Then, on 7 April, news leaked of more cuts. A newly established reporting and advocacy group, OneAid,[5] reported that Washington was cutting USD 1.3 billion from humanitarian aid globally and that Afghanistan was losing all its humanitarian assistance, amounting to USD 561.8 million. OneAid estimated this would affect “at least 15 per cent of the population” of Afghanistan.[6] The following day, the advocacy group said it had “received word that some terminations that occurred last week and over the weekend are being rapidly rescinded.” It turned out, however, that Afghanistan would not be among those countries to see its humanitarian assistance restored.

State Department spokeswoman Tammy Bruce confirmed this on the same day, 8 April 2025: “There were a few programs that were cut in other countries that were not meant to be cut that have been rolled back and put into place.” However, Afghanistan, along with Yemen, would no longer get any US aid, a decision based on what Bruce said were “credible and longstanding concerns that funding was benefitting terrorist groups, including the Houthis and the Taliban.”

Bruce cited a report by the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) from May 2024 that “at least $11 million” in US aid had been “siphoned or [had] enrich[ed] the Taliban.”[7] The reference was to USAID’s implementing partners paying at least USD 10.9 million in taxes and other fees to the Emirate, so not actually enriching individual Taliban, nor the movement. SIGAR did not recommend stopping aid, but increasing “oversight of foreign assistance funds by expanding foreign tax-reporting requirements to all U.S. award agreements and collecting foreign tax reports from implementing partners.”[8] During the Islamic Republic, aid diversion, including of US military spending going to the Taliban, was massive, dwarfing this sum. Referring to this is not to make light of Emirate interference in aid, but Bruce’s reference to the SIGAR report looks to be a flimsy cover for the decision to cut all aid to Afghanistan.[9]

Bruce said the funding was to have gone to the World Food Programme (WFP) in Afghanistan. However, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Afghanistan had a slightly different line, although it noted the same amount of funding had been lost. In a 23 April review of the impact of the US funding freeze, it spoke of “the 4 April decision that all remaining US aid to Afghanistan – totaling $562 million – would be suspended.”

SIGAR has now provided a comprehensive and far worse picture of the situation. It has spoken decisively, not of a ‘suspension’ of USAID funding to Afghanistan, but of its termination, and of cuts totalling USD 1.8 billion. USAID has been left with only two small programmes which support women’s or online higher education.[10]

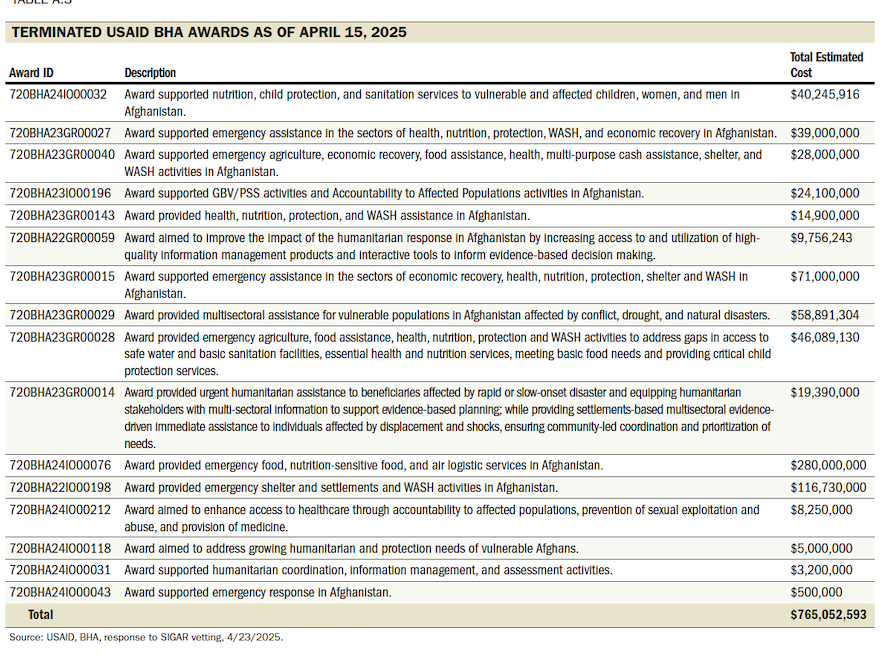

All USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) awards, adding up to more than USD 765 million (a sum greater than that reported by either the State Department spokesperson or OCHA), have been terminated. As Figure 1 below shows, these awards deliver life-saving humanitarian support to millions of vulnerable Afghans, including: nutrition programmes to combat malnutrition in children and pregnant or nursing mothers; healthcare services to address urgent medical needs; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes to ensure access to clean water and proper sanitation facilities; emergency shelter for disaster-affected and displaced populations; protection services for vulnerable individuals, particularly women, children, the disabled and the elderly; and food assistance to tackle food insecurity. BHA awards also supported humanitarian coordination efforts, including logistics and information management, which are essential for effectively delivering humanitarian aid to those in need.

Source: SIGAR Q2 2025 Report to Congress, p10

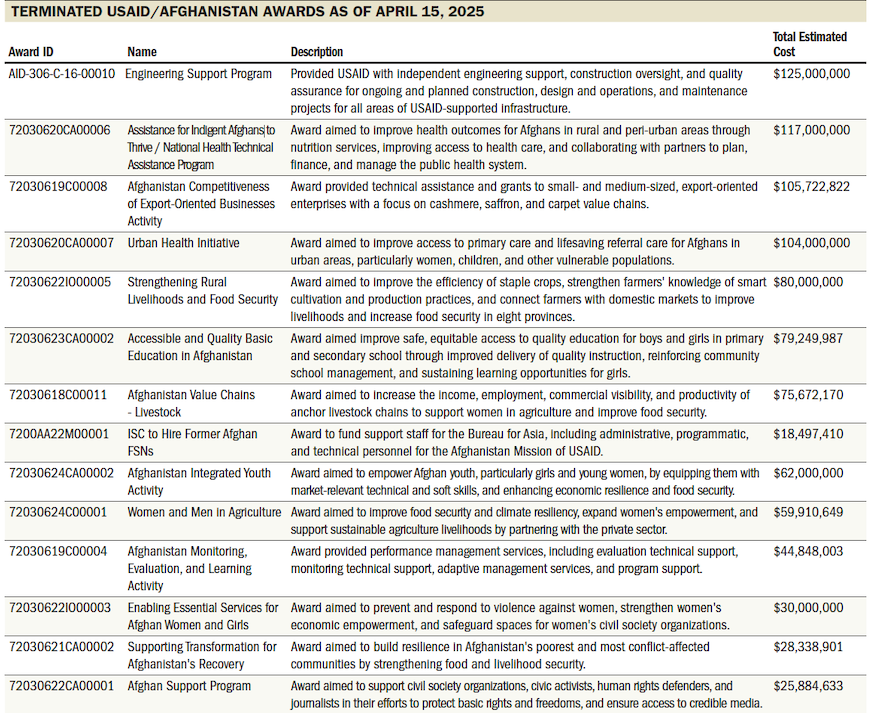

Trump has also cut what are called ‘humanitarian plus’ or ‘basic needs’ funding. Figure 2 shows the programmes cut; they had supported healthcare, agriculture, infrastructure, women’s rights and human rights, civil society, the media, education and the private sector, in total, one billion dollars.

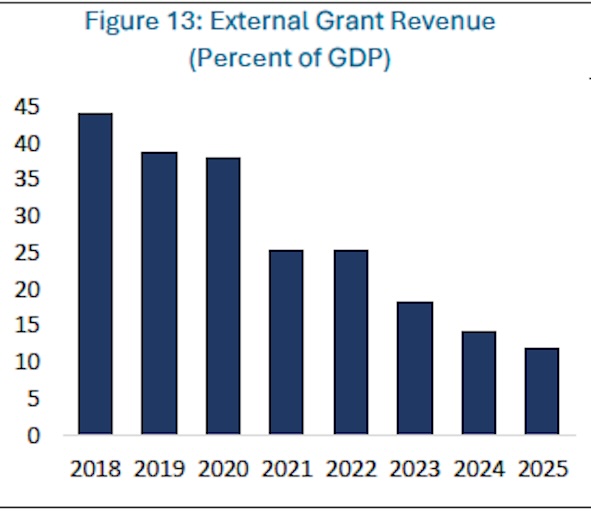

Worth noting are the wider cuts in aid to Afghanistan. Figure 3 below shows that the trend has been relentlessly downward since 2022. Moreover, countries other than the US have, broadly speaking, been maintaining their purely humanitarian aid but cutting non-humanitarian aid, which supports many basic services. As needs in Afghanistan have not diminished, people working in the sector had already felt it was cut to the bone.

The Trump administration’s policies towards two other major institutions may also affect what happens on the ground in Afghanistan. The United Nations as a whole is under pressure from the US government. Along with China, reported The Economist, the US is pushing the UN to the brink of collapse because of late payment of fees. It is already three billion dollars in arrears:

At least China does pay, even if belatedly. Few are sure that America will settle its $2.3bn annual bill. President Donald Trump has wielded an axe to parts of the international system. After taking office he froze funding for international bodies and has sought to abolish America’s aid agency, USAID. He also ordered officials to review America’s participation in all international organisations, including the UN. The results of the review are due in the middle of July. Speculation is rife among UN diplomats over whether Mr Trump will choose savage cuts or, as some recent reports suggest, refuse to pay at all.

In another move, however, Trump has chosen to ask Congress to approve USD 3.2 billion to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), which provides low or zero-interest loans to the world’s poorest countries. “International finance experts,” reported Reuters on 2 April, “hailed the sum, to be paid over three years, as a welcome surprise, given recent worries that Trump could skip making any contribution to IDA.”

The Emirate’s reactions to the US aid cuts

The Emirate has dismissed the allegation from SIGAR and then the State Department that it is diverting aid as baseless. Deputy Minister of Economy Abdul Latif Nazari insisted that it merely facilitates international aid efforts and does not interfere in the distribution of humanitarian assistance. (Afghanistan International) It plays “no role in the aid process and “has not benefited from U.S. aid,” he said.” (Kabul News) The government’s main message, though, repeated at each turn, is that it is wrong to politicise humanitarian aid. For example, Ministry of Economy spokesperson Abdul Rahman Habib, in response to SIGAR’s recent report, said:

Humanitarian assistance, based on global laws and respect for international principles, is vital. In emergencies, disasters, economic crises, and for vulnerable individuals, such aid plays a key role in providing food, water, and access to services. This aid must not be used by some countries as tools of political pressure. (TOLOnews)

Apart from words, there has been no sign that the Emirate is taking any concrete steps to address the impact of the cuts.

The impact of funding cuts

From the tables published by SIGAR (above), it is clear just how many sectors were supported by US funding. Responses and reactions have been coming in from UN agencies, NGOs and aid workers as to how these cuts will affect their work.

The UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Thomas Fletcher, told UN News during a five-day visit to Afghanistan at the end of April/start of May that the humanitarian sector was set to shrink by one-third. In its Impact of US Funding Suspension on the Humanitarian Response, published on 23 April, OCHA said the Humanitarian Country Team had been forced to reprioritise the 2025 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (original here). The focus would now shift to “145 of Afghanistan’s 401 districts with the highest severity of needs as well as the most urgent life-saving activities and protection-related activities.” Of the more than 22 million Afghans in need, it said it would now be helping not 16.8 million people but 12.5 million, with the funding requested reduced significantly – from USD 2.4 billion to USD 1.62 billion. OCHA has provided the following summary of the cuts made to what had been requested and an explanation of the methodology.

Some sectors have published more details than others. The Health Cluster, the only one to consistently report on the effect of the US funding cuts, has said that, as of 29 April, 409 health facilities had closed or suspended their activities, with the southeastern region (Paktia, Paktika, Khost and Ghazni) the hardest hit (72 closed or suspended). The Health Cluster gives no figure for the facilities still open, so the magnitude of the closures is impossible to assess, but it said the closed facilities were serving an estimated three million people.

OCHA has said the cuts would affect the provision of emergency shelter and non-food items to returnees and those affected by disasters such as flooding. Around 20 per cent of the Education in Emergencies Programmes, providing schooling to 166,000 children, has been suspended. The suspension in funding has also had an impact, it said, on multiple projects that were nearing completion – 44 water infrastructure projects, 30 latrine facilities, 29 water supply networks and 22 well constructions. Earlier, on 26 February, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), the UN’s sexual and reproductive health agency, reported that it had been informed that most of its US grants had been cut. For Afghanistan, that meant “more than 9 million women will not receive maternal health and wider services.” This sector was specifically excluded even from the January waiver.

The Nutrition Cluster, with data from 19 March, reported that 396 nutrition sites had closed, affecting 80,000 women and children under five. Reporting by The New Arab/AFP heard from staff at one such centre run by Action Contre la Faim in Kabul that had, at any one time, been feeding 65 children suffering from severe acute malnutrition: the director said it was “painful” for the staff, finishing their last days of work, having to turn parents away, knowing the acutely hungry children faced death.

Some of the major international NGOs have also been reporting on the drastic cuts to the support they give. The International Rescue Committee (IRC), working with Afghans since the 1980s, said on 25 April 2025 that it had been forced to close its community-based education programme for 300,000 children who live in areas without schools. It had also been forced to suspend “critical programs that provide health care, vaccination, malnutrition treatment, clean water and protection services. As a result, over 700,000 people, including refugees and displaced families, will lose access to essential humanitarian services from IRC programming alone.”

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) has said it was having to make cuts to its support for “the most vulnerable Afghans, displaced from their home area by conflict, drought, and poverty.” Its programmes support those living in makeshift settlements and returnees by providing vital services, “assisting returning and internally displaced Afghans by providing support with housing, food, legal aid and referrals to healthcare providers within [their] communities.”

Losses in gathering and sharing information

Getting information about the cuts these last three months has been difficult, with data, both globally and when it came to Afghanistan, patchy. Information-sharing platforms and mechanisms have been compromised by the cuts, while orders from Washington to cut or maintain programmes were often made, but then rescinded or reinstated, sometimes several times.[11] Many organisations looking to find other donors to fill some of the gaps left by the cuts in US aid have also held off making announcements. While the overall picture is now clearer, significant information gaps persistand will extend into the future. Several organisations that have been crucial for providing data or context are no longer operating.

The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) has been dismantled, its staff terminated and its building (the construction and maintenance of which had been partly funded by private donations)[12] taken over by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) with the help of the police. Called in by USIP to protect it from the DOGE agents who had arrived without a warrant, the police broke the locks and allowed the agents to forcibly enter the premises. (Guardian) USIP was set up under Congressional legislation signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1984, and was funded by Congress with an aim to “promote international peace and the resolution of conflicts among the nations and peoples of the world without recourse to violence.” Its takeover by DOGE under presidential orders is being contested in the courts, given that USIP came under Congressional oversight.

USIP was very active in Afghanistan, but all its many insightful reports have disappeared from its now blacked-out website, a huge loss to researchers and policymakers.[13] Its work in Afghanistan, begun in 2002, significantly expanded after 2009 when it established an office and field team in Kabul. That included research and programmes to support the rule of law, promote human rights, prevent and resolve local conflicts (especially land disputes), prevent electoral violence, develop peace education curricula and support dialogue and peace efforts.[14] USIP closed its Kabul office in August 2021, but its range of programmes and research maintained a focus on informing the public and policymakers on the rights of women and girls, humanitarian and development issues, inclusive peace processes, and the regional and international threats posed by violent jihadist groups based in Afghanistan and Pakistan (see, for example, the 2024 launch of a the Senior Study Group’s report that highlighted those risks).

DOGE mocked and belittled USIP after the takeover, tweeting about several allegedly egregious contracts, two of them relating to Afghanistan. As these look like either deliberate or wilfully ignorant claims, we wanted to put some more reliable information into the public sphere. DOGE referred to USIP using private aviation services (these were not perks for USIP staff, but the flights that evacuated staff and family members from Kabul in August 2021) and employing “ex-Taliban member” Muhammad Qasem Halimi. DOGE’s Elon Musk and his (all-male) employees were also filmed by Fox News boasting about their work to other (unidentified) men around a large polished table in a panelled committee room (location unspecified). They mocked USIP and Halimi, alleging there was “no clear description of what services [he was contracted to provide],” describing the money as “going to the Taleban,” and wondering if it had been spent on arms or opium.

Halimi did indeed work at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the first Emirate, more than two decades ago, but also went on to be a highly effective and courageous member of the Supreme Court under President Hamed Karzai. As the Inspector-General, he tried to clean up the judiciary, catching dozens of judges on camera seeking bribes, with the aim of getting them sacked. Without political backing, however, and facing death threats, he was forced to resign (author interview 2010, referred to here). He also had a number of government positions under President Ashraf Ghani, among them, Deputy Minister of Justice and Minister of Hajj and Awqaf. (biography) Halimi was a legal and conflict advisor at The Asia Foundation and worked on national reconciliation for many years during the Republic. He also has strong Islamic credentials as a graduate from Cairo’s al-Azhar University.

Halimi had worked with USIP since 2023 on its Religion and Inclusive Societies programme, advocating for women’s rights, as embedded in Islam, and peace through Islam, work which, given his background, was focused on Afghanistan. That involved research and outreach, holding training sessions, organising conferences and gathering support for Afghan women’s rights from ulema in Turkey, Qatar, Egypt, Iraq and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and persuading them to take up the issue with the Emirate, as he told AAN: “How they could talk to the Taliban about women’s rights – to education and work – and how we could get to peace in Afghanistan, without fighting, both through Islam. I was always working on both tracks.” USIP’s behind-the-scenes advocacy had results, as we alluded to in an October 2024 report when the OIC said publicly that women did have the right to education and to speak and be seen.[15]

Halimi is also well-known on social media, writing largely in Pashto and with the clear aim of reaching out especially to young Afghans. His Facebook page promotes non-violence and a vision of Islam markedly different from the Islamic Emirate’s. One Afghan colleague described him as offering “knowledge and tools based on cultural norms and Islamic principles of equality, peace and justice” as a counter to Taliban ideology and the Emirate’s claim to be enforcing policies grounded in tradition and sharia.

On 14 May, a Washington DC court is due to rule on the legality of the USIP takeover. Lawyers for USIP assert that its status as an independent agency means the president and DOGE lacked the power to dissolve it. Even if the court does declare the takeover illegal, it will not be easy to rebuild an institution decades in the making given the destruction wrought by DOGE in a matter of weeks

USIP has been a significant element in the ecosystem of nuanced and in-depth reporting on Afghanistan, as was a very different organisation, iMMAP, which has also ceased to function. An international nonprofit that provided humanitarians, development organisations and governments with evidence-based information management services to help emergency preparedness and humanitarian responses. Some of its work on Afghanistan can still be seen on its website, for example, its mapping of earthquakes. iMMAP is looking for alternative funding, in the hope of resuming its work.

There is better news for the USAID’s global Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), which monitors agroclimatic and hydrological conditions and hazards and provides early warning of droughts and food crises in vulnerable regions. It was set up in 1985 to prevent a repeat of the famines in East and West Africa and has been critical for supporting governments and humanitarian agencies, including in Afghanistan, to make decisions and respond effectively.

When AAN last reported on the cuts to USAID in February, FEWS NET was offline. However, some reports have now been posted by the US Geological Survey. They include the all-important seasonal monitors for Afghanistan (most recent on 29 April 2025) which report/forecast rain and snowfall, temperatures, harvests, flooding etc. The Geological Survey is a member of FEWS NET’s science team, a “multiagency, multidisciplinary collaboration dedicated to the monitoring of agroclimatic and hydrological conditions using satellite data, on the ground observations, advanced analytical tools, and expert knowledge.”

What aid workers are saying

AAN also heard from people who work for NGOs and UN agencies, all but one Afghan, about their experiences on the ground. A senior manager with an international medical NGO said they had been receiving most of their funding – USD 35 million – from USAID. Losing that support, he said, has had a “direct and drastic impact on our organisation.” In March, he said USAID had told them it would be “providing the money for live-saving projects … and we should continue our work. Then, in April, they told us they would not be providing any funding at all.” The NGO has had to lay off 60 per cent of its staff, ie 600 people in 15 provinces. It has closed some clinics and is considering pulling out of some provinces altogether. The manager was still working and hoping for an overturning of the US ban on aid to Afghanistan, but admitted the situation was taking its toll:

When you work in an office for several years, you build your career and capacity, so this cut-off of aid has a psychological impact, especially on the young people, because there are no other job opportunities in Afghanistan. There simply are no job opportunities in other offices, except for NGOs, and cutting off aid creates the fear that we might all lose our jobs.

A senior manager with another NGO that works mainly in Nangrahar province in health, education, community development and social response, also said they had been hard hit: “With the cut of a large portion of funds,” [our work in] almost all of these sectors have been affected. … Without funds, you cannot implement any project.” Even the work that was still going on, supported by other donors or for which they had had advance funds, was affected because “the entire organisation is shaken by the cuts in American funds,” he said.

Everyone [in the organisation] is frustrated and thinks their job can be terminated at any time. The workload has increased because so many employees are leaving, and things are just not normal. It feels like it did during the August 2021 Taliban takeover: nothing is clear and everyone is wondering whether their job will be terminated or their salary cut.

For him personally, there were also consequences. After hearing by email that he should stay at home until further notice, his salary was stopped.

It’s been difficult for me and my family because, living in Kabul with no other source of income, we relied on that salary. It’s like blood in the veins. So, when that stops, life stops. From the very beginning, I understood that depending on a salary had these problems. One of my sons does work in the government, and we now rely on his salary and my savings. To be honest, it’s changed many things in practice. We’ve moved to a cheaper house – the rent is lower and so is the standard. I’ve also moved my younger sons and daughters from one private school to another with lower fees.

An international aid worker at one of the major NGOs described the mood as sombre, with organisations, employees and people in the communities they served all grappling with the uncertainty. “It’s very hard for organisations to see a shrinkage in their capacity to respond at a time when so many Afghans are returning [from Pakistan and Iran]. And the timing! Such a sharp increase in need and such a sharp decrease in our ability to adequately respond to everyone’s needs.”

Two people supported by USAID via an aid contractor also spoke to AAN. One, the owner of a carpet-weaving business, had benefitted from a project which aimed to modernise the industry. The project provided technical and financial help, modern looms, apprenticeships and training at every stage, including to herders who provide the wool, dyers, weavers as well as help with marketing and export. She told us the end to support had meant job losses and she was worried about the wider impact, predicting greater unemployment and more poverty.

A man working for the contractor on an agricultural support project said that of 160 people, only two were still working. As a senior person in human resources, he had overseen the lay-offs, but was now due to lose his own job at the end of May. He described his sadness and worry about the difficulties he would have covering rent and household expenses and lamented that he would no longer be able to send money to his little brother studying in Russia.

We also spoke to someone in a specialised technical role for a UN agency that had been providing WASH and health services and emergency support. He said their operations would be closing in most of Afghanistan, given that US funding had made up half their entire budget. In their agency, he said, around 30 to 40 per cent of colleagues had lost their jobs and salaries had been halved for those who remained.

80 per cent of employees had been laid off at the Kunduz office of a major international NGOs that has provided healthcare, water, sanitation and hygiene, education and agricultural support, said one of its managers, who was still working because his salary was not dependent on USAID. His laid-off colleagues were in a very bad economic situation, he said, but it was worse for their beneficiaries, who were now missing out on schooling and water, sanitation and hygiene programmes.

We hope to hear from beneficiaries in a future report, to better understand how the cuts are manifested on the ground.

How will the cuts impact the wider economy and public services?

These snapshots of people working in NGOs or private business or UN agencies give a glimpse of what the cuts will mean on the ground. They will directly affect millions of Afghans, both beneficiaries and workers. The impact will ripple out, seen in incomes lost, money not spent and goods not bought, on out to businesses with no direct connection to aid losing customers, and to the government losing revenue, in the form of lower tax and customs receipts.

The latest World Bank Afghanistan Development Update was published on 23 April 2025, ie before the SIGAR report revealed the full extent of the US funding cuts and does not specifically mention those cuts, but references “aid disruptions” and a “sharp decline in aid.” Yet, indirectly, it does highlight the magnitude of the loss of US aid.

It reported a decline in aid in 2024 of 42.8 billion afghanis (USD 600 million or 4.23 per cent of GDP) to 204 billion afghanis (USD 2.9 billion, or 14 per cent of GDP). The cut in aid in 2025, will be far higher. In the light of ‘disruptions to aid’, the Bank had already lowered its growth forecast for this year, to around 2.2 per cent (less than population growth, so a fall in per capita GDP). It had based this calculation on a forecast of a cut in aid this year of about 600 million USD. Now that SIGAR has published its report, it is evident that the actual cut will be far higher and the impact on growth much greater.

Afghanistan is a country that was flooded with unearned foreign income for twenty years, not only civilian aid, but also military support and spending by foreign armies. The sudden loss of most of that, overnight, in August 2021 – with some restored as emergency humanitarian aid that winter – led to a 25 per cent contraction of the economy. Since then, aid has been steadily declining (see figure 3 above). The new loss from the United States this year is not on the same scale as August 2021, but it is also sudden and will still make a substantial dent in the economy. Aid funding helps pay for the trade imbalance – Afghanistan imports more than it exports, and many of those imports are essentials – food, fuel and medicine. The aid is largely in the form of cash dollars, necessarily flown in because of sanctions-related problems with making international banking transactions, and that helps with liquidity.

There will also be knock-on effects because of what the aid paid for – which the Emirate has chosen not to fund. In its October 2023 Development Update, the World Bank summarised the priorities of Emirate government expenditure as “utilizing available resources largely to pay for security, teachers’ salaries, and core civil and administrative functions while leaving donors to finance healthcare, food security, broader education needs, and the agri-food system.” The figures have been stark: in 2022, the Emirate spent 60 per cent of its operating expenditure (which takes up almost all of the budget) on the security services – army, police and intelligence – and only 1 per cent on health, a choice which it has not pulled back from.[16] The Emirate’s choice of priorities left the health sector vulnerable to cuts in aid and, indeed, with the sudden stop to US funding, hundreds of clinics have already closed. Already, in relation to the much smaller decline in aid seen in 2024, the World Bank’s latest Development Update had concluded that the reduction posed “a serious risk to the continuity of essential service delivery programs, particularly those implemented through the UN and funded via humanitarian channels.” It explained:

Key sectors such as healthcare, education, and social protection which have historically relied on international aid, may face severe disruptions, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations, including women, children, and displaced communities. The contraction in aid may also limit emergency response capabilities, further straining public services and slowing economic recovery efforts.

We are now seeing that risk realised. In the short term, a humanitarian crisis looks likely, especially given that the mass deportation of Afghan refugees from Pakistan is only sharpening needs. As the UN’s Tom Fletcher has said: “There will be deaths.” In the medium-to-long term, the damage to health and education will also have an economic cost by reducing the country’s ‘human capital’. This is in addition to the economic harm done by the Emirate’s restrictions on girls’ education and women working and travelling, not just to individuals and their families but also the country’s prospects for development.

Apart from calling on the US not to politicise aid, there have been few comments from the Emirate, nor any sense that ministers are taking action to try to mitigate the damage to public services. The Emirate’s priorities in earlier years – expanding the workforce (tashkil), especially that of the security services and the Ministries for Promoting Virtue and Preventing Vice, and Education – have left it with little room for manoeuvre. Or at least, changes to its spending priorities would likely be politically more difficult than letting health clinics close.[17] The Emirate is also already preoccupied with making swingeing cuts to the public sector, cutting a fifth of both civilian and military jobs (we hope to report on this soon).

In its April 2025 Development Update, the World Bank described foreign aid as “once a key driver [of the economy which] has declined significantly since the Interim Taliban Administration took power.” Yet, the massive unearned income (aid, military support and spending by the foreign armies) that flowed into Afghanistan under the Republic drove growth that proved to be a chimaera, a bubble economy that burst when the money went. The vast quantities of on-budget aid also facilitated flourishing corruption in government and an administration unresponsive to the people, yet still able to runpublic services. While the sums now coming to Afghanistan are far smaller and there is scarcely any on-budget aid, the funding has still enabled the Emirate to deploy government revenues (taxes, customs and other receipts) to build up the coercive powers of the state, while underfunding basic services. That has meant, as well, that when and if aid did decline, those services were vulnerable.

The cuts to US and other aid, and the cuts to public sector jobs, will be a double blow to millions of Afghan families. As to how to respond, households have already used up available strategies or those strategies are no longer available. They have drawn down savings, borrowed where they can and found marginal income, for example, pulling older boys out of school to work or women doing piece work at home. As for the ‘traditional’ tactic when times are hard, of sending men to other countries for work, Pakistan and Iran are forcibly returning Afghans. For the economy as a whole, the obstacles that followed the Taliban capture of power in 2021 – frozen assets and UN and US sanctions (despite waivers, international banking is still deeply problematic) – are all still in place. Just to increase the potential misery this year, FEWS-NET has forecast that the wheat harvest may be reduced because of below-average precipitation and below-average soil moisture. All in all, 2025 is looking to be a difficult year for Afghanistan and its people.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour

References

| ↑1 | The waiver was to allow “existing lifesaving humanitarian assistance programs,” so long as the resumption was temporary and no new contracts were signed. It applied to “core lifesaving medicine, medical services, food, shelter, and subsistence assistance, as well as supplies and reasonable administrative costs as necessary to deliver such assistance,” but specifically not family planning. However, there were few staff to deal with requests for waivers after almost all staff were put on administrative leave and overseas staff ordered to come home on 7 February. See the announcement here, the only message left on the USAID website. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The figures are from page 64 of SIGAR’s second quarter report toCongress this year, published on 30 April 2025. |

| ↑3 | See Ian Mitchell and Sam Hughes, USAID Cuts: New Estimates at the Country Level, Center for Global Development, 28 March 2025. |

| ↑4 | GNI comprises the total annual market value of all the final goods and services produced in a country, plus a number of other types of overseas income, but not foreign aid, or remittances. See this explanation by the Centre for Economic Policy Research. |

| ↑5 | OneAid describes itself a “nonpartisan group of humanitarian assistance, international development, and national security professionals, partners, and others … [who] have come together to advocate for continued foreign assistance and the preservation of our democracy.” It said the information had come from former and current USAID experts and partners and the list was based on first-hand confirmation (NPR also subsequently confirmed the figures with its own sources). Other countries affected included: Syria USD 237.3 m; Somalia USD 169.8 m; Lebanon USD 148.2 m; Yemen USD 106.5 m; Jordan USD 58 m; Gaza USD 12.3 m; Niger USD 8.7 m. |

| ↑6 | On 18 March, the man who had been in charge of USAID, Pete Marocco – it was his signature as Director of Foreign Assistance at the State Department and USAID Deputy Administrator, reported NPR, that “appeared on many of the administration’s directives, including orders to cancel 5,200 of USAID’s anti-poverty and health-care programs and to shrink the agency’s workforce to a couple of hundred people” – sent an email to a number of colleagues that USAID was now “under control, accountable and stable.” That day, he also handed over control of what remained of the agency to a 28-year-old Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) employee, Jeremy Lewin, who, reported both Rolling Stone and The Guardian, has serious criminal allegations against him. Lewin also subsequently took over Marocco’s main job as director of Foreign Assistance at the State Department after Marocco left government for reasons unknown, a move reported on 13 April (Guardian, AP). |

| ↑7 | SIGAR’s report, U.S. Funds Benefitting the Taliban-Controlled Government: Implementing Partners Paid at Least $10.9 Million and Were Pressured to Assistance, was based on interviews with implementing partners who spoke about paying taxes, utilities, customs and fees since August 2021. It reported that:

A quarter of respondents had experienced direct pressure from the Taliban, including involvement in and approval of program design and implementation; access to facilities or use of resources or vehicles; recruiting or hiring of certain Taliban-approved individuals; or diverting food and other aid to populations chosen by the Taliban. In addition to direct pressure on implementing partners, some respondents stated that the Taliban have regularly inquired about ways to obtain donor funding, including through the establishment of Afghan NGOs.” However, despite, “facing harassment by members of the Taliban security forces, the majority of implementing partners reported being able to successfully decline the requests. |

| ↑8 | SIGAR noted this in its second quarterly report to Congress in 2025, already cited in the main text, on page 7. |

| ↑9 | Ashley Jackson’s October 2023 report for AAN, Aid Diversion in Afghanistan: Is it time for a candid conversation?, looked into the allegations against the Taliban government and provided a nuanced and rounded account. For more on corruption under the Republic, see SIGAR’s 2016 investigation, Corruption in Conflict: Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan. |

| ↑10 | They are: the Promote Scholarship Endowment, formerly Women’s Scholarship Endowment, which provides university scholarships for Afghan women in the fields of science, technology, engineering and maths, which, as of June 2024, was supporting 59 women to study in Qatar and Turkey (to be terminated early, on 30 June 2025, rather than 28 September 2028); and Supporting Student Success in Afghanistan, which funds online learning through the American University of Afghanistan, “with the goal of increasing access to higher education in Afghanistan.” As of autumn 2024, it was supporting 1,007 students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programmes. It is scheduled to close on 30 December 2026. |

| ↑11 | Hana Kiros for The Atlantic, in Emergency Food for 3 Million Children Is Stuck in DOGE Limbo, has a cogent look at the chaos and lack of communication in the cancellation, reinstatement, and quiet re-cancellation of one programme, a US-made nutritional foodstuff that “Elon Musk said he would preserve,” but which “the Trump administration [then] quietly canceled.” |

| ↑12 | For a general breakdown of USIP’s funding sources, see this @ResilientEffort post on X. |

| ↑13 | For the patient, the USIP website can still be found on Wayback Machine. One hundred USIP reports about Afghanistan can also be found on Relief Web. |

| ↑14 | AAN worked with USIP on two series of ground-breaking reports (published 2018-21), ‘One Land, Two Rules’, which looked at service delivery in insurgency-affected districts, and ‘Living with the Taleban’, which explored local experiences of Taliban rule: all can be read in this dossier. It also funded an important report, published just before the Taliban takeover, which heard from women in rural areas about their hopes for peace and fears of war, and an investigation into the fate of Community Development Councils (CDCs), upon whom such hopes for development had rested, but which were abolished by the Emirate.

We benefited from having USIP’s economist, Bill Byrd, as a guest author: his keen eye helped unravel the good and the bad from Republic-era budgets (for example, here). Reform of the public finances, which was begun under Finance Ministers Eklil Hakimi and Khalid Payenda, would have been foundational to getting the whole government running better and more cleanly and actually serving the public. This is a naturally dry topic, but we felt it was consequential and could be gripping in the hands of a good writer. USIP’s Scott Warden’s assertion in a guest piece, Why the West Should Care about Afghan Election Fraud, ahead of the 2010 parliamentary elections, was also important. |

| ↑15 | Halimi writes on his Facebook page that in response to Elon Musk’s and DOGE reporting a “baseless accusation” that he was involved in “suspicious activities,” he has filed a legal complaint, demanding the restoration of his reputation and integrity. “Let’s see what the justice and court system in the United States decides,” he writes. |

| ↑16 | For the 2022 figures on health and security, see the World Bank’s October 2023 Afghanistan Development Update. See also figure 13 of its December 2024 Afghanistan Development Update for the split between civilian and security spending over several years. Data on public finances from the Emirate is scarce, but occasional information suggests little has changed. |

| ↑17 | For reporting on this, see these earlier papers by AAN, Survival and Stagnation: The State of the Afghan economy, 7 November 2023 and What Do The Taleban Spend Afghanistan’s Money On? Government expenditure under the Islamic Emirate, 16 March 2023 |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign