Afghanistan Analysts Network

The novel, Shabnam, by the Bengali writer Syed Mujtaba Ali,[2] written in the mid-20th century, has recently been translated into English by Nazes Afroz. The 1920s was a period when Afghanistan was going through a turbulent time. King Amanullah (r1919-29) saw his authority challenged by internal and external forces until a fully-fledged civil war broke out in 1928-29, and chaos replaced order. Mujtaba Ali was then a teacher at Habibia College in Kabul and witnessed these events. He wrote two books: a memoir in 1949 titled, In a Land Far from Home – A Bengali in Afghanistan, also translated by Nazes Afroz into English (see AAN’s review), and later a novel called Shabnam (1960), which is the focus of this review.

Mujtaba Ali (1904-74) was born into a Saayed family in Karimganj, then part of Sylhet district in British India (Kaptai.club).[3] He briefly studied at Aligarh Muslim University, although the exact dates of his time there are not clearly documented in available sources. He was, however, one of the first students to enrol in Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, graduating in 1926, before moving to Kabul in 1927 to take up a teaching position. He later continued his studies at the University of Bonn in Germany and Al-Azhar University in Egypt, going on to teach in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). He left East Pakistan after falling out with the Pakistani authorities, who sought to impose Urdu as the sole state language, and relocated to India, where he worked for All India Radio before returning to Visva-Bharati University as a professor of German language and Islamic Culture. He was said to speak 12 languages.[4] His knowledge of Persian seems to have been exceptionally deep and extensive. This comes across quite clearly in Shabnam, as we will see in this review.

Mujtaba Ali’s presence in Afghanistan was by no means an isolated instance. Soon after Amanullah acceded to the throne and secured full diplomatic independence from the British, he sought to bring educated foreigners to Afghanistan as teachers and advisers for the civilian and military state departments (read this AAN report). Fellow Muslims or, at any rate, individuals from neighbouring Asian countries were preferred. For many South Asians sympathising with India’s struggle for self-rule, such as young Mujtaba Ali, Amanullah’s Afghanistan represented an attractive destination, thanks to its anti-colonial credentials and open support for Indian freedom fighters. However, the reformist programme on which the Afghan king had hastily embarked had already started to meet strong domestic opposition (such as the Khost rebellion explored in this AAN report). Soon after Mujtaba Ali arrived in 1927, the number of those opposing King Amanullah’s reforms grew and it did not take long for turmoil and violent disorder to break out. Threatened by revolts from both the Pashtun tribes of the eastern region and the mostly Tajik inhabitants of the Shomali Plateau, Amanullah would eventually abdicate in January 1929. Foreigners hurried to abandon the capital as it was seized by Habibullah Kalakani, who proclaimed himself king.

Love in a time of civil war

It was against the backdrop of civil war that Mujtaba Ali conceived Shabnam, setting his love story within the very upheaval he had witnessed. The novel follows Majnun, an Indian teacher, reminiscent of the author himself, who observes the swift reforms introduced by King Amanullah with interest, and questions whether they have the public’s support and reflect the attitudes and cultural sensitivities of the Afghan people. During an evening stroll near the king’s palace, he encounters Shabnam, a young Afghan woman, bright, educated and liberal, who has recently returned from France. She shares his concerns about the unrest stirred by the king’s reform agenda. Their brief encounter sparks an unspoken desire for more frequent meetings and gradually their love for one another deepens beyond their control and they marry. But the violence and lawlessness of the civil war ultimately crushes their love. The depth of the story, reflected in Mujtaba Ali’s Bengali-style narrative, makes it into an interesting and engaging read and the translator has tried to reflect the Bengali flavour in the English translation.

A witness to chaos

On one level, Shabnam comes across as an eyewitness account of a wandering lover who happens to be in a country undergoing major social change and the attempted transformation of its system of governance. Social order is disrupted; anyone can do anything without fear of legal consequences. It appears that the writer, through a fictional format, intends to expose his Bengali readers, who had been living in peace, to the consequences of social instability and disorder. In this sense, Shabnam appears to be reinforcing his previously written memoir, In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan, by providing an eyewitness account within a novel of how the Afghan government of the time disintegrated until it ultimately gave way to lawlessness.

Afghans who lived through the period immediately after the 1978 coup d’état by the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) and during the mujahidin rule in the 1990s will be all too aware of what can happen to people regardless of gender, age and nationality when social order is disrupted in a turbulent time. For Afghan readers over the age of 50 who lived in Afghanistan in their youth, the story may resonates with their own experiences.

From Mujtaba Ali’s own non-fictional account of his life in Afghanistan, the existence of a similar liaison with an Afghan woman can be ruled out. However, as Nazes Afroz has suggested, the inspiration for the story could have been derived from the many real-life instances of people – friends and lovers – whose lives were abruptly swallowed up in the maelstrom of the civil war (The Daily Star).

Perhaps Shabnam, the woman, can also be read as a personification of Afghanistan itself, a country with which Mujtaba Ali quickly fell in love, only to lose it just as abruptly. In 1929, he left Afghanistan, never to return. It is possible that he had fallen in love with the ‘new’ Afghanistan that was being born during King Amanullah’s reign, an Afghanistan that soon disappeared forever.

Mystical layers of the dewdrop

The novel, Shabnam, however, traverses more than one level. Beneath the surface, and reflecting historical events, other deeper layers have been woven into the story, which require more analysis. These more profound meanings can be seen in a number of clues that suggest the story may have been inspired or influenced by the mystical and Sufi content of classical Persian literature, of which Mujtaba Ali seems to have been aware. This knowledge may have inspired the choice of the title.

Here, we outline some of these clues.

The first, and most important, clue seems to be the title Shabnam, which is also the name of one of the two main characters in the story.

Shabnam means dewdrop in Persian and is a popular name for girls. It is very prominent in both classical and modern Persian literature and has been extensively used as a literary device by poets and scholars. In the so-called Indian Style of Persian poetry, the image of the dewdrop develops further, coming to symbolise humility, love, the brevity of life, the annihilation of the self, devotion and becoming one with the Whole. At its core, the dewdrop is a rich and multi-layered symbol that reflects the mystical ideas of unity and impermanence, as well as the relationship between the part and the Whole. It often represents the human soul – small and seemingly separate, yet composed of the same essence as the ocean. This is used in literature to symbolise the relationship between the individual soul and absolute reality.

A dewdrop vanishes as the morning sun rises – just like the world of shadows and illusions. It is a reminder of the transient nature of life. Its brief existence reflects the fleeting nature of worldly life. In the story, Shabnam appears in Majnun’s life, bringing a world filled with happiness, joy, hope and poetic beauty, but then vanishes, leaving behind a void that can never be filled.

The dewdrop also suggests that truth cannot be found by clinging to the current form of being, but rather by dissolving into the Beloved (or the Divine). So, by turning into vapour and disappearing, in this genre of Persian poetry, the dewdrop becomes one with the sun and ultimately becomes the Sun. It disappears, not into nothingness, but by merging into a greater reality. This illustrates fana’, the Sufi concept of annihilation of the self in the ultimate reality. Small as it is, a dewdrop can reflect the entire sky, suggesting that even the humblest soul, if pure and still, can mirror the infinite beauty. It is a symbol of spiritual receptivity and inner clarity. This symbolism is not abstract for Mujtaba Ali: it becomes embodied in Shabnam herself.

Names as symbols

In the story, Shabnam – the dewdrop – is the central character, alongside her lover Majnun, who shares a name with one of the central characters in Layla and Majnun, the classic tale of love and longing to which we will later return. During their brief but immensely joyful encounters, Shabnam and Majnun often quote classical Persian poets to express their thoughts and feelings, weaving literary references into their dialogue. Those quoted include the 10th-century poet, Kisai Marwazi, and the 17th-century poets Kalim Kashani, Sa’eb Tabrizi, and Salim Tehrani (referred to in the book as Ali Quli Salim). Significantly, Salim, Kalim and Sa’eb are prominent figures in the Indian Style of Persian poetry, while Kisayi belongs to an earlier period and, unlike the other three, is not known to have spent time in the Indian subcontinent.

There are also quotes from Hafez Shirazi (14th century) and Mawlana Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi, also known as Rumi (13th century). Majnun, the protagonist of Mujtaba Ali’s story, claims that Rumi is his “favourite poet” (page 121). The story also mentions Nizami Ganjavi (the 12th century author of the most famous Persian version of Layla and Majnun, who many believe transformed a simple story into a complex mystical study), alongside Ferdowsi Tusi (the 10thcentury author of Shahnamah, or The Book of Kings) and Nuruddin Abdur Rahman Jami, the 15th century author of another version of Layla and Majnun (pages 37 and 153). This shows that Mujtaba Ali’s knowledge of Persian poetry goes beyond the Indian Style. He seems to have had a much wider knowledge of the Persian literary heritage.

The poets mentioned above have woven mystical concepts into their poems. However, none of the Persian poems quoted in the story specifically mentions shabnam/dewdrop, which in itself is interesting. It is difficult to determine whether Mujtaba Ali deliberately chose to avoid poems that explicitly mention the word and reveal the deeper meaning of the story. He may have intentionally built this ambiguity into the story, as is the norm in Persian literature, where almost every piece can have dualities of meanings embedded within it. At the early stages of Shabnam and Majnun’s relationship, a poem is quoted from an unknown Indian or Bengali source, which includes the phrase “dewdrop.” However, this poem is more about the separation of the flower from the plant and the dewdrop is used in a descriptive form for the flower:

I am thy companion

Oh, night jasmine, the dream of autumn night, drenched in dewdrops

The pain of separation

When Shabnam asks what it means, Majnun interprets the poem as carrying the following meaning:

We have a flower in our land – shiuli[5] [the night jasmine]. The poet says the autumn dreams the whole night for it to bloom – but the shiuli falls to the ground at dawn immersing the plant with the pain of separation.

Persian poets quoted by Mujtaba Ali wrote multiple poems specifically about the shabnam/dewdrop, including some related to the central theme of the novel, for example, this line from Kalim Kashani:

شبنم به بال جذبه خورشید می پرد

The dewdrop flies on the wings of the sun’s allure

Or this from Sa’eb Tabrizi:

به قرب گلعذاران دل مبندید

وصیت نامه شبنم همین است

Don’t get attached to worldly pleasures

So reads the last will of the dewdrop

There are many poems by these and other poets named in the story that include the word ‘shabnam‘.

Echoes of Layla and Majnun – and differences

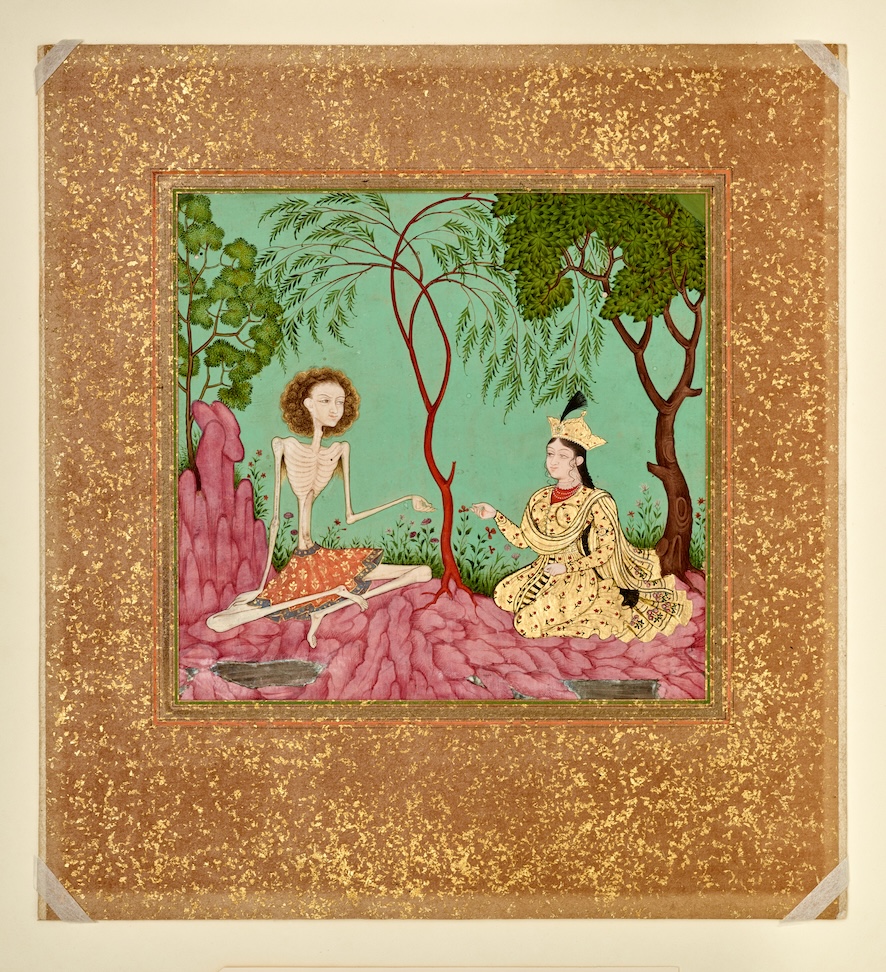

Another interesting clue lies in the story’s fable-like quality, which recalls the classical tale of Layla and Majnun. First recorded in Arabic, the tale became a prominent feature in Persian literature, where it was given poetic form by the 12thcentury poet Nizami Ganjavi as part of a collection called Khamsa, and retold in the 15th century by Mawlana Nuruddin Abdul-Rahman Jami in a collection titled Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones). Each retelling introduced variations in detail, yet the essential elements of the story remained the same. (Other classical poets, including Amir Khosrow Dehlawi, also wrote versions of the story, but here we focus on those specifically named in Mujtaba Ali’s novel.) Over time, Layla and Majnun became one of the most widely known and frequently retold love stories in the Persian-speaking world.[6] Essentially, Layla and Majnun is a tragic love story about Qays and Layla, whose pure and passionate love is thwarted by societal pressures and family opposition. Qays, deeply in love with Layla, becomes so obsessed with Layla’s love that he earns the epithet ‘Majnun’, meaning ‘possessed’ or ‘mad’. Despite their love, the young couple are kept apart, leading Majnun to wander the desert in a state of poetic madness. In Persian literature, the story explores themes of divine love, longing and the pain of separation, ultimately portraying love as a spiritual journey beyond worldly obstacles.

While people may have viewed Layla and Majnun as a powerful story of two human souls mad with love for each other, in Sufism, the story is often interpreted not merely as a tale of earthly love, but as a profound allegory for the soul’s yearning for union with the Divine and so takes on a much deeper meaning. Majnun’s obsessive, all-consuming passion for Layla is symbolic of the divine longing that overtakes a seeker of the true path. Beyond the name of one of the central protagonists in the novel, there are references to Layla and Majnun in several other places.

In Mujtaba Ali’s story, Majnun meets Shabnam in Kabul on the fringes of a lavish party held by King Amanullah and falls in love with her, but unlike the classic tale, Majnun marries Shabnam. The marriage stands in for the joys of Layla and Qays’ early encounters, while the unruly bandits of the civil war are reminiscent of the family opposition that keeps Qays/Majnun away from Layla. Otherwise, the lovers meet a similar tragic end in both versions. Nonetheless, the variances make the two stories different in relation to the concept of junun (the madness of love). In the classical story of Layla and Majnun, ‘reason’ is confronted in various ways and at multiple levels throughout the story. Initially, both families are too proud (in other words, ‘too mad’) to consider a relationship with the other. While Majnun’s family eventually relents – after they notice the profound change in his condition – Layla’s family never does. To the very end, they are unwilling to give in to logic or reason. Majnun gives up living with people and chooses to live in the wilderness. Attempts by family and well-wishers to change his mind fail. The dominance of love’s ‘madness’ continues to the very end and is perhaps also the reason why Majnun was seen as a more fitting name for Qays. In a couplet in chapter two of the Mathnawi, Mawlana Balkhi/Rumi endorses love’s madness and expresses it slightly differently:

آزمودم عقل دور اندیش را

بعد ازین دیوانه سازم خویش را

I have tried the far-thinking intellect;

Henceforth I will make myself mad

In Mujtaba Ali’s Shabnam, Majnun’s family is absent from the scene (they are in the faraway land of Bengal) and have no direct say in the matter. Shabnam’s family, by contrast, comes across as considerate and cooperative. Shabnam’s father devises a well-thought-out plan – albeit somewhat opportunistic given the circumstances – to secure the future happiness of the lovers.

Unlike in Layla and Majnun, where family opposition and Majnun’s inner madness drive the tragedy, here the ‘madness’ lies instead in the environment and the turmoil of the civil war raging in the country. The combination of her family’s cooperative attitude and the civil war gives Shabnam the tenor of a realistic love story, anchoring the mystical aspects.

While the tale of Layla and Majnun is referenced in the novel, an interesting account of it unfolds on the night of Shabnam and Majnun’s wedding when the couple reminisce over their encounters and recite Layla and Majnun to each other. This may sound like they are trying to indirectly compare their love to that of Layla and Majnun, which is not just earthly love but love on a higher plane. To make sure we do not miss this divine and mystical plane, they leave us with this revealing remark: “The mortal body of this world could not hold on to such death-defying love any longer. Holding hands, Layla and Majnun were going to Heaven, walking on the rainbow” (page 156).

Poetry as mystical testimony – and silence as eloquence

The story of Shabnam is not written entirely in prose: there are many lines of poetry, and this might sound a little unusual in English. English readers may not be accustomed to a mix of poetry and prose in the same piece of writing. However, for readers familiar with classical Persian (and Arabic) literature, this aspect of the story seems quite natural. In Persian, writers and thinkers have written in a mixture of poetry and prose for centuries.

One important point to consider is that, in modern Persian literature – at least in Afghanistan – there are very few recent works of prose with mystical content that can serve as models for new writers. Earlier poets looked to their predecessors for inspiration: Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi/Rumi drew his inspiration from Fariduddin Attar and Sanayi Ghaznawi and transformed their mystical visions to create his own unparalleled body of work, which continues to inspire people around the globe, while the 17th century Indian mystical thinker and poet, Bedil Dehlawi, drew on Balkhi/Rumi, Saʿdi, Hafez and others. This chain of influence has allowed poetry to carry the mystical tradition forward, generation after generation. Prose, however, has lacked such a lineage.

For modern writers of prose who are interested in mysticism, this absence creates a kind of vacuum. To bridge the gap, they have to do what Mujtaba Ali does in Shabnam – weave lines of poetry into their narratives, encouraging readers to reflect on the deeper mystical meanings through the authority and resonance of verse. The story of Layla and Majnun referenced in Shabnam was written in Persian verse, not prose. Mujtaba Ali may therefore have felt the need to rely on classical poetry to strengthen the mystical content of his story, positioning Shabnam as part of this ongoing dialogue between verse and prose.

The poems he quotes provide another pointer towards the mystical aspects of the story. As an example, note this couplet from Kalim Kashani (on page 23):

دل گمان دارد که پوشیده است راز عشق را

شمع را فانوس پندارد که پنهان کرده است

The simple heart thinks it has hidden its love under a veil

The lampshade thinks it has hidden the candle’s flame

In other words, in the same way that the lampshade cannot hide light, love also reveals itself, a maiden, betrayed by her blushing, who cannot conceal her love (see below). This couplet from Sa’eb Tabrizi is also quoted (page 30):

خموشی حجت ناطق بود جان های واصل را

که از غواص در دریا نفس بیرون نمی آید

Nazes Afros follows Mujtaba Ali’s Bengali translation of the couplet:

He who dives deep looking for the pearl

Bubbles if his exhalation does not swirl

However, a literal translation might provide a clearer link to the story:

Silence is the eloquent proof for souls who have converged,

For from the diver deep in the sea, no breath returns to the surface.

Running the risk of oversimplifying the meaning of this couplet, one can say that in the same way that a diver cannot hide being in water by holding his breath, a lover’s silence speaks just as eloquently and clearly to give away his love. In other words, silence, in itself, becomes the evidence.

Silence becomes a conscious effort, an active withholding and suppressing of sound, a deliberate act of surrender, of allowing oneself to be overwhelmed. It is not a passive absence, but an action that suggests the pursuit of union. In this light, silence itself becomes a form of testimony.

In the same way that light cannot be hidden by the lampshade love also reveals itself and becomes public. Elsewhere in the story, this same concept is reinforced by a quote from an unknown Sanskrit source for which the author provides a translation (page 39):

I asked: oh maiden,

Will you love me or no?

She blushed;

And her heart hid her love.

Nezami Ganjavi’s Layla and Qays try to keep their love secret, but the more they try, the more they fail:[7]

کردند بسی به هم مدارا

تا راز نگردد آشکارا

کردند شکیب تا بکوشند

وان عشق برهنه را بپوشند

They showed much tolerance of each other,

so that the secret would not be revealed.

They endured patiently and strove,

to cover the naked flame of that love.

Mawlana Jami takes a different position: Layla complains that while Majnun could speak out, should he wish to, she is destined to remain silent:[8]

رازی که توانیش تو گقتن

من نتوانم به جز نهفتن

عاشق غم دل به نامه پرداز

معشوق و به جان نهفتن راز

The secret that you can speak out

I can do nothing but keep hidden

The lover pours out the heart’s pain in letters

The beloved conceals the secret with her soul

Poets have used various metaphors to make this point. Some of them have used scent or light (as in Kalim Kashani’s lines above) to illustrate love’s revelatory qualities. In the same way that no flower can contain its scent and no lampshade can contain light, no human soul can contain love. And silence transcends speech, gaining a more expository power in love than words could.

Love, reason and faith

This emphasis on silence is echoed and reinforced in the lines quoted from non-Persian sources, which also portray love as a miraculous and transformative force defying normal human logic and reasoning. In Persian literature, Rumi is recognised for his exploration of the distinction between reason and love. Love goes where reason dares not tread. Reason is often seen as divisive, while love resolves differences and bridges gaps by fostering unity. For example, note these lines from Chapter 6 of Balkhi/Rumi’s Mathnawi:

عقل راه نا امیدی کی رود؟

عشق باشد کان طرف بر سر دود

لاابالی عشق باشد نی خرد

عقل آن جوید کز آن سودی برد

How could ever reason take the path of despair?

It is love that runs there with its head (rather than feet)

Carefree is love, not reason

Reason seeks what brings it gain

Rumi finds reason clumsy and incapable of answering deeper philosophical and mystical questions, for which love does provide an explanation. On this issue, Mujtaba Ali uses a quote from a Sanskrit source in which a well-known nonbeliever, Charvaka, the founder of materialism and atheism in ancient India, is recalled by the story’s character Majnun as being overwhelmed by love and breaking with his materialistic and atheistic self by kneeling to confess belief and embrace faith:

Only for a day in life, Charvaka

Knelt before the creator

Only for a day, blessed by love –

Joyous was the day – a day of hope

This quality of love can be traced in the work of most Persian literary giants. The following lines from Mawlana Balkhi/Rumi express a similar meaning:[9]

کافر صدساله چو بیند ترا

سجده کند زود مسلمان شود

A hundred-year-old infidel, upon seeing you

Would fall in prostration, swiftly embracing faith

Another mystical aspect of love – of interest to us as it is reflected in Shabnam – that has been extensively covered in classical Persian literature is that love does not bring comfort and ease; it brings inexplicable pain. Pain becomes the yardstick for feeling the depth of love. Lovers welcome pain, and in their view, those who cannot endure pain cannot be true seekers of love. Here are some examples from the poets quoted in the book, the first two are by Sa’eb Tabrizi and the second two by Kalim Kashani.

ما را زعشق درد و غم بیکرانه است

For us, from love comes boundless pain and sorrow[10]

عشق دردی است که درمان هزاران درد است

Love is a pain whose only cure is thousands of pains[11]

عشق را بخت تیره در کار است

جلوه شمع در شب تار است

Love requires a dark fate

To be a candle in the darkest night[12]

از در و دیوار می بارد بلا در راه عشق

Calamities pour down from everywhere in the path of love[13]

A lover who cannot accept and endure pain is not considered a lover. As in the examples above, most sources do not distinguish between love and pain: love is pain. In Shabnam, the author uses a quote from an unknown Sanskrit source (on page 67) to make this point:

There is pain in meeting the foe

More pain in losing a friend

If both inflict so much torment

Who will tell who is foe, who is friend?

In these lines, the boundary between friend and foe is lost. When a friend (or the loss of a friend) can bring you more pain than a foe does, then what is the point in trying to distinguish between them? In other words, love leaves you with unending pain. Love and comfort do not go together. This seems to be the message Mujtaba Ali conveys through the story of Shabnam.

Mujtaba Ali’s Legacy

Taken together, these themes suggest that Mujtaba Ali’s message in Shabnam is not limited to politics or personal romance. Rather, the novel points towards a wider mystical vision. While there are numerous other clues in the book, the purpose of this review is not to provide an exhaustive analysis of all of them, which might spoil the plot for readers and risk becoming repetitive. The aim is to analyse some key elements, such as the title and the names of the two leading characters, the link with the classical mystical tale of Layla and Majnun and the poems quoted in the story, to draw attention to the deeper mystical content of the novel. This helps us reach a slightly different conclusion. The author may have pursued a paradoxical and multi-layered goal. For his Bengali readers, who may never have experienced the absence of law and order in their own lifetime, he may have aimed to open a window on the chaos of the civil war and how it disrupts everyday life. At the same time, he may have wanted to make use of his extensive knowledge of Persian literature and expose his readers to mystical concepts and thinking by producing a story that does not end. Rather, the text finishes with the Persian phrase, ‘Tamam na shud’: It did not end. In the same way that life does not end with death in the mystical world, love and the story of love continue beyond the illusions of earthly life; lovers die, but their love remains beyond the reach of death.

A closer look at Mujtaba Ali’s background lends weight to this analysis. His father, Khan Bahadur Syed Sikander Ali, “traced his paternal descent to Shah Syed Ahmed Mutawakkil, a Sufi Pir” (see Sylhet: History and Heritage), suggesting Sufism and mysticism had deep roots in the family and that Mujtaba Ali was exposed to it from a young age. In 1921, he enrolled at Visva-Bharati University, which had been founded that year by the Nobel Laureate poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, whom Ali knew personally. These two pieces of information help us understand Mujtaba Ali’s profound grasp of classical Persian literature as well as his knowledge of mystical concepts in Sanskrit. Tagore’s short story ‘Kabuliwala’, about the filial bond between an Afghan vendor and a five-year-old Indian girl, may have inspired the affection Mujtaba Ali felt towards Afghans and Afghanistan (see AAN’s Afghanistan in World Literature (III): Kabuliwalas of the Latter Day).

By writing Shabnam, the author offered a precious gift to his host country, Afghanistan, where there were few examples of prose with mystical content. Afghan poets have continued to keep the Sufi tradition alive, incorporating mystical concepts into their poetry in both classical and modern formats. It is not easy, however, to find such examples in prose. Two writers from Iran, Ghasem Hasheminejad and Mostafa Mastoor, have written stories in prose that continue the mystical history. Elephant in the Dark, Hasheminejad’s most famous novel, is a modern detective story but draws on mystical concepts. His other work, a short story, Kheirunnesa: A biography, also has mystical concepts woven into it. Iranian author, Mostafa Mastoor’s Persian-language bestseller, Kiss the Fair Face of God (Rouyeh Mah-e Khoda ra bebus), is known for its mystical content.

Similarly, the late Afghan writer and philosopher Sayed Bahauddin Majrooh maintained an interest in the classical heritage and juxtaposed modern psychology with philosophy in relation to mystical thinking in his novel Azhdaha-e Khodi (The Ego Monster). Azhdaha’e Khodi is not a love story and it is not at all similar to Shabnam: it provides a more accessible comparison of Western philosophy/psychology with Sufi/mystical thinking. Another work of Afghan literature which brings in Sufi concepts is the 2018 novel by Asadullah Habib titled Dar Sawahil-e Ganga (On the Banks of the Ganges/Ganga).[14] It concerns the life and work of the great 17th century mystical poet and thinker, Mirza Abdul Qadir Bidel, and was published in Kabul. In the novel’s fictionalised format, Habib uses story-telling language with great skill to make some of Bedil’s complex metaphoric and mystical concepts more easily accessible to readers. The novel takes the reader through various stages of Bedil’s life, punctuated by deep philosophical and mystical questions and dilemmas.

Such examples are scarce, however, and none were available to Mujtaba Ali when he wrote his story. Therefore, Shabnam would sit alongside the very few examples of mystical philosophy in modern prose fiction from Afghanistan, and possibly the wider region.

Mujtaba Ali’s novel is, therefore, more than just a love story interrupted by Afghanistan’s civil war. It stands at the crossroads of history and mysticism, bearing witness to the collapse of a fragile state while submitting to the reader that love is eternal – that it can endure beyond death, chaos and reason. Weaving Persian, Sanskrit and Bengali strands into a single narrative, Mujtaba Ali gave Afghanistan a rare example of mystical prose with a modern edge, while also offering his Bengali readers a glimpse into a world they might never otherwise have known. In this way, Shabnam endures as a timeless reflection on how beauty and love can survive even when empires crumble and nations transform.

Mujtaba Ali shows us how mysticism and mystical values remain relevant to modern life, even when social attitudes have shifted. Tales such as Layla and Majnun, Shirin and Farhad[15] and Bejan and Manija[16] sought to challenge social norms and temper human pride. Shabnam, by contrast, belongs to a world where, while attitudes to love may have shifted, civil wars, failed governments and intolerance continue to wreak havoc on societies. Seen in this light, Shabnam reminds us that mysticism and its values still hold the potential to help societies move beyond conflict and restrictions and toward tolerance and peace. If Layla and Majnun was a commentary on personal pride and worldly attachments, Shabbam extends the criticism to social disorder, poorly-conceived and hastily implemented reforms and the violence of civil war – all forces that dispossess millions and continue to shape lives in our own time.

Edited by Fabrizio Foschini, Roxanna Shapour and Rachel Reid

* Shirazuddin Siddiqi was a lecturer at Kabul University’s Faculty of Fine Arts until the start of the civil war in 1992. He then worked for the BBC’s Afghan Education Project (BBC AEP), eventually as director, producing a range of educational and development programming for Afghan audiences, including the radio soap opera, ‘New Home, New Life’. In 2012, he led the localisation of BBC AEP, which is now operating as the Afghan Education Production Organisation (AEPO). He was also the BBC Media Action Country Director for Afghanistan, 2003-17

The author wishes to thank Ferdous, Arian and Wida Siddiqi for reading the book and/or the review to share their thoughts, which inspired him to consider new issues that he had not initially included. Likewise, thanks are due to Ubaidullah Mehak, Jolyon Leslie and Zia Dastur for being the sounding board on the wider cultural scene in and around Afghanistan. Special thanks are due to Baqer Moin for sharing information on writers in Iran, to Ismael Saadat for finding Dr Habib’s book in Kabul and making it available in time for this review, to David Morton for revising and editing this book review, and to Nazes Afroz for treating the author with copies of the books right after their publication.

References

| ↑1 | The quotation opening this report is from the novel; Majnun cites Alexander Pope to explain how children in Kabul could be outside playing during fighting, without fear because they were innocent, whereas adults, fearing to die, were hiding in their homes. The quotation is from Pope’s ‘Essay on Criticism’, 1711, translated by Nazes Afroz from Mujtaba Ali’s Bengali translation of Pope’s (more famous) original wording: “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread!” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Syed Mujtaba Ali, Shabnam, translated by Nazes Afroz, New Delhi, Speaking Tiger, 2024. The title of this book review was inspired by a poem by the 17th century Indian Sufi poet, Mirza Abdul Qader Bedil (also known as Bedil Dehlawi), who is considered one of the greatest Indo-Persian poets:

From this rose-garden, we have reached the wondrous state of the dewdrop A door to the abode of the sun must be opened |

| ↑3 | At the time of Mujtaba Ali’s birth in 1904, Karimganj was a subdivision of Sylhet district, which then formed part of the Assam Province of British India. Following the Partition of 1947 and the Sylhet referendum, most of Sylhet joined East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), but Karimganj remained in India. Today, it is a district in the state of Assam, while Sylhet lies within Bangladesh. |

| ↑4 | Nazes Afroz mentions that Mujtaba Ali spoke 12 languages in his 2015 English translation of In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan, published by Speaking Tiger Publishing. The Bengali newspaper, The Daily Star, lists 15. |

| ↑5 | The flower, shiuli (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis), seems to enjoy a similar position in Indian literature and mythology, as shabnam does in Persian literature. |

| ↑6 | Scholars have counted dozens of full versions in Persian and Turkish, with many more in Urdu, Azeri and other languages, alongside countless oral and lyrical adaptations. It is reasonable to assume that Mujtaba Ali’s readers would have been familiar with both the literary and the mystical resonances of the story and recognised Shabnam as a retelling of this classic tale in a modern and different context. |

| ↑7 | Nezami GanjavI, Diwan-e Kamel (The Complete Collection of Poems); Khamsa: Layla and Majnun, p 386. |

| ↑8 | Mawlana Nuruddin Abdur Rahman Jami, Mathnawi Haft Awrang, Awrang-e Shashom: Layla and Majnun, page 773. |

| ↑9 | Mawlana Jalaluddin Mohammad Balkhi/Rumi, Kuliat-e Shams Tabrizi, Ghazal number 1005. |

| ↑10 | Sa’eb Tabrizi, Diwan-e Ash’ar, Ghazal number 1994. |

| ↑11 | Sa’eb Tabrizi, Diwan-e Ash’ar, Ghazal number 1445. |

| ↑12 | Kalim Kashanai, Diwan-e Ash’ar, Ghazal number 55. |

| ↑13 | Kalim Kashanai, Diwan-e Ash’ar, Ghazal number 63. |

| ↑14 | Dr Asadullah Habib, Dar Sawahil-e Ganga (On the banks of the Ganges), Zaryab Publishers, Kabul, 2018, ISBN: 9789936615403. |

| ↑15 | Shirin and Farhad is a famous Persian romance as told by Nizami Ganjavi in Khosrow and Shirin. Farhad, a sculptor, falls in love with Princess Shirin. King Khosrow, Shirin’s suitor and Farhad’s rival, sets him the impossible task of carving a tunnel through a mountain to win her hand. When Khosrow later deceives him with false news of Shirin’s death, the grief-stricken Farhad takes his own life. |

| ↑16 | Bejan and Manija is another classic Persian love story drawn from Ferdowsi’s Shahnamah. Bejan, a Persian prince, falls in love with Manija, the daughter of the Turanian king, Afrasiyab. Their forbidden love leads to Bejan’s imprisonment in a deep pit, from which he is eventually rescued by Rustam, the hero of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings). |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign