Afghanistan Analysts Network

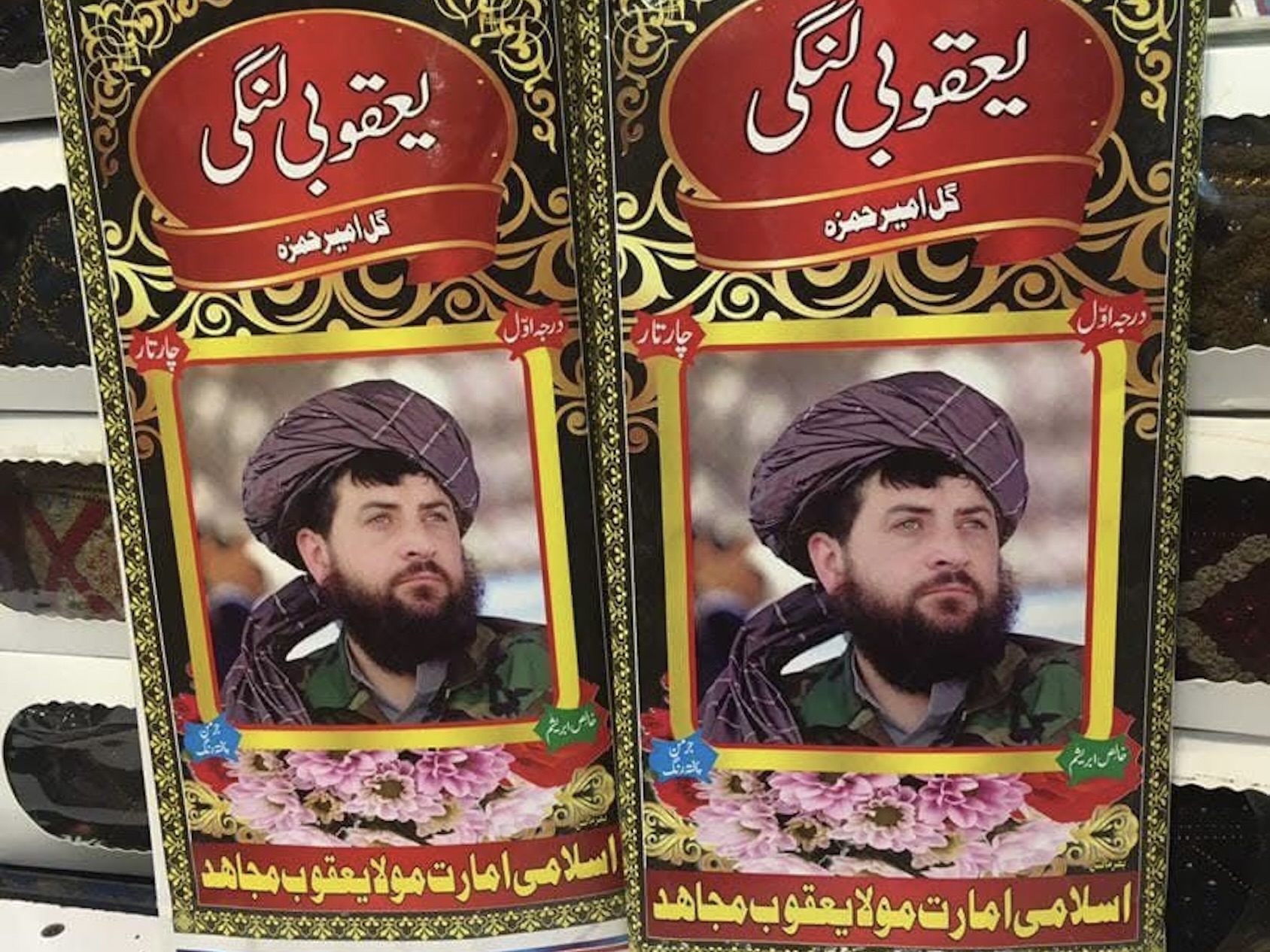

A Yaqubi turban on display in a shop in Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, owned by a member of the Taliban

A Yaqubi turban on display in a shop in Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, owned by a member of the Taliban

This report, which focuses on the experiences of former Taliban members and supporters, begins by looking at the background of how the Taliban entered into business during the insurgency and where and how these business activities took place. It then explores how many of them have turned to commerce following the establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), bringing their small businesses from the rural areas to the cities and scaling them up. It examines what kinds of businesses they have established and how they are performing. Finally, it considers the cultural and economic implications of this shift, both for the Taliban as a movement and for the broader Afghan economy. The research is based on more than 25 in-depth conversations with business owners, who mainly moved to Kabul from rural areas or from Pakistan after the August 2021 takeover. It also draws on the author’s multiple visits and first-hand observations of these businesses, as well as informal conversations with business owners and observers throughout the past four years.

Background: a divided country

When the Taliban began their war against the United States-backed Islamic Republic in the early 2000s, they primarily operated in the rural areas of particular provinces. Over the years, they eventually built up a presence in districts across most of the country, although always in the rural areas, while the government maintained control over the urban centres. The amount of territory each side controlled remained contested throughout the conflict, though it became clear that the Taliban were steadily expanding their presence. By the end of 2019, they were effectively in control of over 70 per cent of Afghanistan’s territory.[1] However, nearly all provincial capitals and most district centres remained under the Republic’s control, almost until the end.

More importantly, throughout these two decades of insurgency, the divide between Taliban and government-controlled areas was not only territorial but also, to a considerable extent, social and economic. Communities and businesses were often split along these lines. Since each side controlled different areas and had their own supporters, the hostility extended beyond the battlefield and into daily life. People living in Taliban-controlled areas, regardless of their personal affiliations, could be labelled as Taliban or Taliban supporters and vice versa. This perception meant that crossing into territories held by the opposing side was dangerous and those doing so risked harassment, violence or arrest by the dominant force. To avoid such risks, people from both sides often tried to avoid entering the other’s territory as much as possible. Many of our interviewees from Taliban-controlled areas confirmed this. One said he “never visited Gardez [Paktia’s provincial capital] because many of our people were arrested on charges of being a Talib.”[2]

Taliban-affiliated interviewees, when, for instance, describing how the authorities of the Republic treated them, observed that arbakis (pro-government militia or Afghan Local Police) were particularly harsh. “They knew which village was under Taliban control,” one Taliban-affiliated business owner said. “So when you faced them at a checkpoint, they would ask, ‘Where are you coming from?’ If you said that village, they would arrest and beat you. They’d say, ‘Why do you shelter and feed the Taliban?’ and would only release you after paying a ransom.”

Several interviewees said the provincial government and Afghan National Army generally treated people better and did not harass those from Taliban-held areas. Even so, cases of wrongful arrest and mistreatment still occurred due to misinformation or flawed intelligence.[3] One man, now a restaurant owner said:

I was going to Ghazni city from our village and got stopped at a checkpoint near the city. They pulled me out of the car and beat me. Someone had told them I was Mullah Hamza [a Taliban commander], but I told them I wasn’t. They kept me for two days until they accepted I wasn’t Hamza.

Most Taliban families were forced to engage in some form of economic activity to survive as most of the movement’s fighters joined voluntarily and most did not receive salaries or other forms of financial help. Nearly every family had to find a source of income, so those fighters worked part-time or other members of their family stepped in.

However, the opportunities of the cities could be out of bounds for those coming from Taliban-controlled areas. They were often recognisable based on appearance or conduct, or through intelligence, and many were arrested while visiting government-controlled areas. One interviewee, who described himself as a Taliban supporter and is now living in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), recalled:

I opened a shop in Sharana [capital city of Paktika province]. A month later, someone from the government was killed near my shop. The police came and blamed me. I was arrested and my shop was shut down, all because I was from Wazakhwah [district] and had a beard. I spent three months in prison and after paying 30,000 afghanis [roughly 450 USD], I was released. My shop was shut [during this period] and I sold it. I never tried to start a business there again.

This dynamic effectively cut off a large swathe of the population from the broader economy and the privileges and business opportunities that existed in urban centres where the government held control. As a result, they had limited access to markets where most commercial activity was concentrated and economic prospects were significantly better than elsewhere.

Yet people from Taliban areas, as well as part-time Taliban members themselves needed to support their families and, for some, contribute financially to the movement. However, their options were limited. Some managed to stay in urban areas, taking strict precautions to avoid detection and maintain a low profile. But even then, it was risky. One current employee of the Ministry of Interior, who was a part-time fighter during the Taliban’s insurgency years, told AAN:

I was working in a restaurant and studying at the university. I changed my appearance and shaved my beard. On Fridays, I’d come back to the village and go to the mujahedin [Taliban], then return to work on Saturday. For two years, I worked in Kabul without anyone knowing. But then, a spy from our area exposed me and after that, I never went back home to Chak [district of Wardak province].

One of the economic possibilities that Taliban supporters and part-time fighters opted for was migrating to the Gulf, especially to countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia. A Taliban supporter from Ghazni said:

I was harassed several times during the Republic. Once, they came to our village and arrested me on charges of being a Taliban just because I had a beard. That’s when I joined the jihad. My father wasn’t happy and got me a visa to Dubai. I went there and started working as a labourer. I used to send a small share of my income to my dilgai [a military unit of Taliban]. Now, my business is successful: I have friends in the Emirate and my own license [work permit].

Even in the Gulf, there could be difficulties for people with links to the Taliban. Security services in the host countries carried out detailed checks and surveillance, often identifying such people as potential threats. Many, according to interviewees, were deported. One frequent accusation against people from Taliban-held areas was that they were collecting funds for the movement. Having Taliban-related content on their phones such as videos, taranas (unaccompanied, chant-like poetry) and speeches made things worse, as was talking about the insurgency in phone calls or chats with people back in Afghanistan. Many of those detained or deported over such charges were not Taliban members but rather people who had connections with them.

During the insurgency, as the Taliban gained prominence and took control of more territory, what began to emerge as a better alternative was establishing businesses into Taliban-controlled areas. When some local bazaars and district centres fell into Taliban hands, many members and supporters began to establish businesses there. For example, in Wardak province, when the Taliban took control of large parts of Band-e Chak around 2018 in Chak district, a local bazaar also fell under their control. One interviewee explained how he set up a tailor shop there:

I set up my shop in Band-e Chak where the Emirate was in control. During my tashkils [tour as a Taliban fighter], my younger brother looked after it and when I returned, I’d join him. It didn’t earn as much as tailors in Maidan [Maidan Shahr, Wardak’s provincial capital] made, but it was still enough to cover some household expenses.

Working in Taliban-controlled areas brought its own difficulties, including the contested nature of control over those places. Interviewees said that in some areas, control of a bazaar would shift back and forth between the Taliban and the government, creating instability and uncertainty for Taliban fighters who were also trying to run businesses. However, interviewees noted that the situation improved in the later years of the insurgency as Taliban rule in the areas they held became more stable, particularly in the south and southeast and even some central provinces, such as Logar and Wardak.

Another challenge was the local economy itself. Compared to the major marketplaces in district centres and provincial capitals, these local bazaars were only partially functional. They lacked both a strong customer base and the variety of goods and services necessary for sustainable commercial activity. Many people in these areas bought only basic items locally and still relied on larger bazaars for most of their needs due to better prices, quality and selection.

A more viable option for some was Pakistan. During the insurgency years, Pakistan offered the Taliban movement sanctuary and had long been a primary destination for Afghans – both as refugees and as economic migrants. For some of those who could not do business inside Afghanistan, Pakistan was a good solution. Many Taliban members relocated there with their families, combining business activities alongside their involvement in the movement, as this interviewee described:

Life became difficult. Our house was raided twice. I wasn’t home and was moving between Pakistan and Afghanistan on tashkils, so I decided to move my family to Pakistan as well. There, I established a bakery to survive and cover our day-to-day expenses. During my absence, my brother would take care of it and when I was there, we ran it together. I was doing both baker and mujahed.

Another interviewee shared a similar story:

I did jihad for three years in Paktika province. But when my father passed away, things changed a lot and I had to take full responsibility for the family. I couldn’t openly work in the city because of the risk of being identified and arrested. Some friends in Pakistan reached out and offered me a job and I went there. My friend had a perfume shop and I started working with him. After a year, I opened my own shop. During tashkils, I’d leave the shop with a friend, join the jihad for a few months, visit home and then return to Quetta.

The choice of what business to establish was not just about what individuals could afford or manage practically, it was also about what aligned with their social circle and if there was a customer base they could easily access. Operating in areas populated by other Afghan refugees, they mostly targeted people from their own communities, as well as Pashtuns from the Pakistani side of the Durand Line. This interviewee, for example, made and sold Afghan bread:

I had a bakery on Mall Road in Peshawar. The people living in the surrounding areas were all Pashtuns and [Afghan] refugees and we all knew each other. That made it easier as we knew their language and what their expectations were.

Those in Pakistan often relied on their social networks to operate informally, since many lacked legal status. Still, their businesses were fragile there too as at times they were arrested by the Pakistani government. There have been waves of deportations of Afghans from Pakistan over many years, both before and after the fall of the Republic, including a major campaign to evict Afghans in 2016 (Guardian). One interviewee for this report was arrested and deported to Afghanistan, leaving his business behind. He alleged that all the goods were stolen from his shop as he was unable to go back for months.

The military takeover and its consequences

By mid-August 2021, the Taliban controlled almost the entire country. Fighters and supporters who had long operated in rural areas or across the border in Pakistan now seized the opportunity to enter the cities and urban areas that had long remained under the Republic’s control. At the same time, many city dwellers and business owners, widely regarded as connected to the Republic, chose to escape, fearing the wrath of the new rulers. Crowds rushed into Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, desperate to catch one of the evacuation flights.

For many of those gravitating into the cities, it was a new experience, as one Taliban fighter, from Paktia province, explained:

When I was grown up, at 17, I joined the jihad. Before that, I’d never left my village. I couldn’t go anywhere. So when the fatha [victory] came, I first moved to [Gardez city in] Paktia and then to Kabul. It was the first time I saw such a big city.

Others with ties to the Taliban shared similar stories. One man told the author that a week after the Taliban takeover, he made his first visit to Kabul in more than twenty years. The last time he had been there was during the First Emirate in the 1990s. Another Taliban fighter who had been living in Pakistan said:

My friends [in the Taliban] called me after Nimruz was liberated. A few days later, other provinces also fell. My heart was with the jihad, so I decided to move to Afghanistan without telling anyone. I left early in the morning on the day Kandahar was taken by the mujahedin. For the first time, I crossed the Boldak border openly and took a taxi to Kandahar. In the past, we had to go through qachaqi [smuggling] routes. I happily joined my friends and never went back to Pakistan.

In the weeks that followed, more and more people visited the cities. Taliban fighters who were already in urban areas welcomed these rural visitors, offering them food, a place to stay and even access to government buildings, including previously sensitive sites like the previously US-controlled Bagram Airfield. Their clothing and appearance reflected the Taliban’s rural style, which made them stand out from city residents, many of whom did not wear turbans, caps or shalwar kameez.

Over time, for the former Taliban or their supporters, these visits, which started as celebrations or sightseeing, turned into something more practical – taking advantage of new economic opportunities. As the Taliban tightened their control over government institutions, many members and supporters became influential in the new order. They were given priority in state jobs, access to resources and other opportunities that had previously been out of reach.

Even being able to move freely in cities like Kabul – whose economy was bigger and stronger than most other parts of the country – was a big change for many. The new political situation, combined with better security and access to those in power, made cities more attractive than before, encouraging many rural men to start businesses in urban centres, especially in Kabul. Many others began moving their businesses from rural areas or Pakistan into Afghan cities. Some relocated shops they had already run elsewhere, while others started afresh. One Taliban-affiliated interviewee from Paktia explained:

In the past, we couldn’t do business in government areas because they’d harass us. Now that security is established, anyone can do business in all 34 provinces. We used to have a tailor shop in Janikhel bazaar, but business wasn’t good. People were poor and I made very little profit.

For many Taliban members and supporters, they wanted to find opportunities to earn a better living. They therefore opted for urban centres which have stronger markets, more customers and more business opportunities. One interviewee described the difference this way:

Across Afghanistan, Kabul is the only place where business is a little better. In rural areas, people don’t spend much and importing goods [to rural areas] is costly. That’s why Kabul and Jalalabad are better choices – the chances of making a good living are higher.

Taliban supporters who moved into cities had now suddenly become the new elite. Their loyalty to the movement gave them better access to state services. Several interviewees said that Taliban-affiliated businessmen were able to get business licenses more easily and were rarely harassed by tax officials (at least not with the same severity). This provided them with a more stable and friendly environment for doing business, as one Taliban-linked businessman explained:

I had a market [a large building that hosted almost a hundred shops] in Kabul, but I didn’t go there much before. When I was building it, I had to pay 200,000 [USD] in bribes to Mumtaz Agha [Abdul Rabb Rasul Sayaf’s nephew] just to get permission. The municipality would come and stop our work. But with the Emirate, those problems disappeared. Now, no one dares ask for bribes and no one interferes because we’re from Zurmat and have turbans and beards. Those days are gone. After the fatha [victory], I built two more 10-storey buildings without any issues.

In some cases, men from rural areas were given long-term leases on government land to set up new businesses. One bakery owner from Wardak province was invited by a Taliban commander to open a bakery near a large military base and was promised a contract to supply bread for thousands of army soldiers. In another case, a shop inside the Wazir Akbar Khan mosque compound in central Kabul was rented to a Taliban-affiliated businessman.

Many of the IEA’s members and supporters who had been living in Pakistan no longer saw a reason to remain there. For years, they had sought refuge across the border because of war, political repression or their affiliation with the movement. But with the fall of the Republic and the establishment of a government they were part of, the motivation to return became strong.

Meanwhile, the situation in Pakistan began to deteriorate for Afghans. In 2023, Pakistan announced that Afghan refugees must leave the country by 1 November (IRC). Increased pressure on Afghans, as well as Pakistan’s own economic decline, created an increasingly hostile environment. Businesses that had once operated freely began to face restrictions and the overall space for economic activity shrank. Returning became the logical economic choice, as one returnee explained:

We didn’t go to Pakistan for fun, but out of necessity. Now, the problems that took us there have been solved. Afghanistan is safe, there is an Islamic system and even the economy is better than Pakistan’s. Even if we earn only half of what we did there, it’s still better because here, we live in freedom under our own system.

Some individuals who initially stayed on in Pakistan after the August 2021 takeover found it increasingly difficult to remain. One interviewee described running his business for another year, but eventually choosing to relocate due to the Pakistani authorities worsening treatment of Afghans and the breakdown in relations between Pakistan and the new Afghan government. As the two sides distanced themselves from the other, Pakistan withdrew various forms of support from the IEA and harassment increased. “One year after the fatha, the [Pakistani] police would come and demand bribes. They even started arresting us for no reason,” said a tailor. “That’s when I started thinking seriously about moving back.”

The situation escalated further when the mass forced returns of Afghans, including Taliban affiliates, began in late 2023 (AAN). At that point, many had no choice but to return, as another man explained:

We had no option but to migrate to Pakistan before because there was no space for us in our own country. But now, thanks be to Allah, there’s an Islamic system and everyone’s rights are respected. People can live freely, within the boundaries of sharia. So, there was no reason to stay there anymore. The only thing we had was our shop. After some time, we sold it to a Punjabi and moved to Kabul. I opened a new shop here and now I feel thankful to be back in my homeland.

Business takeover, Taliban-style

The businesses that the Taliban and their affiliates have established in Kabul so far tend to be small to medium-sized enterprises in different sectors. Popular among them are bakeries, restaurants, tailor shops, stores selling cosmetics, fabric, perfume and similar goods. Many of these entrepreneurs were already familiar with such businesses from the time of the insurgency and their years living in Pakistan. What gave them an additional incentive was the relocation of their customer base from Pakistan to Afghanistan. One interviewee, a shoe store owner from Logar, shared his experience of moving his shop from Pakistan to Kabul:

In Peshawar, I owned a boutique. When the fatha happened, I closed my shop there and came back to Afghanistan. After some time, friends encouraged me to reopen in Kabul since my two brothers were unemployed. So, I rented a shop in Shahr-e Naw and re-decorated it. At first, there were very few customers and the shop barely covered its costs. But over time, as I focused on advertising, it improved and now it’s making a good profit.

Another interviewee, who already owned a tailor shop in Charkh bazaar of Logar province, opened a more fashionable shop in Microrayon neighbourhood of Kabul. He explained that he was already well versed in tailoring. Similarly, others started enterprises in fields where they had experience. A restaurant owner, for example, opened a restaurant serving the same menu he had successfully run for years in Pakistan.

Consumer goods offered by these Taliban-affiliated businesses exhibit some distinct differences from the Republic era. For example, in the fashion and cosmetics sector, many shops sell items that reflect the Taliban’s cultural preferences. These include styles of turbans named after prominent figures like Minister of Defence Mullah Yaqub and Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, reflecting the styles they wear (see this BBC Pashto report, which has some pictures, and this the US seller offering the Yaqubi turban – “SUPER RARE!!! Mullah Yaqoob Lungi – Afghan Lungi – mujahideen turban – Pashtoon Turban – Taliban Turban – Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” – for USD 140). Taliban-affiliated businesses also sell traditional hats such as Kandahari caps and pakols, different styles of chadar (shawls), both guldozi(machine-embroidered) and khamak (hand-embroidered), as well as popular fashion items such as ‘Skechers-style’ footwear. Other commonly sold items include tasbih (prayer beads), meswak (natural toothbrush sticks), Arabian perfumes, signet rings and other jewellery, including Al-Fajr watches that display prayer times.

In the tailoring sector, many specialise in clothes that match the distinct Taliban style. Their shalwar kameezzes are different from those worn by ordinary people – typically wider, with more embroidery and a unique cut for the shalwar that requires specialised tailoring skills. In the restaurant sector, many businesses serve South Asian dishes popular in Pakistan, such as biryani (spiced rice with meat), dudh patti (milk tea) and paratha (fried flatbread).

One characteristic of many of the new businesses emerging in Kabul is a strong Pakistani influence. This is most notable in the restaurant sector, where many ventures are nearly exact replicas of businesses that the owners once ran in Quetta and other parts of Pakistan. Just as burgers and pizzas became commonplace under the Republic, now customers can find Pakistani-style foods that were not traditionally common in Kabul’s culinary scene. Apart from the menus, they have also copied the names and interior designs of their Pakistani counterparts. Initially, their customers were mostly people who had lived in Pakistan and were familiar with these foods. However, as one restaurant owner observed, local Kabul residents have gradually started to embrace and enjoy these new flavours and according to one, “biryani is quickly becoming a favourite food for many Kabulis.”

Another example is a well-known perfume business, Al Makah Khushboo Mahal, which operates several branches in Kabul’s Wazir Akbar Khan neighbourhood. The business is originally from Pakistan and retains a typical Urdu naming style common in Pakistani fragrance stores, often involving an Arabic name. The interior design of these shops also closely mirrors the style of similar businesses in Pakistan.

Most of the interviewees expressed confidence in their businesses, with many reporting that they are not only sustainable, but expanding. One of our interviewees initially got a job in government when he moved to Kabul from Quetta, but found the salary too low:

So, I opened a tailoring shop in Chaharrahi Abdul Haq. In the beginning, only my friends and mujahedin came, but slowly I gained a reputation because I made good quality clothes thanks to my experience in Quetta. During Eids, I hired three more workers in addition to the two I already had because I couldn’t refuse orders and the existing staff wasn’t enough. We all slept only three hours a day, working day and night. Now, I make twice what I could make in the government job and I’m my own boss.

With so many Taliban members and supporters having moved to Kabul, and also being first in line for jobs, and with good contacts in the government helping their economic status, they are the core customer base of these new businesses. In many cases, there are already strong personal and business ties between owners and customers. Some had served the same customers before, in rural areas or in Pakistan, which has helped them rebuild their base in Kabul. As many people from those areas have also relocated to the city, they continue to support the businesses they trusted before. One fragrance shop owner explained:

Most of my customers are mujahedin, because they’re the ones who like the kind of perfumes I sell. We also offer turbans and caps like Yaqubi and Muttaqi, as well as chadars and tasbih. These are the things that mujahedin use the most. And there are many of them in Kabul now and if you know how to market, you can attract a lot of customers.

This steady demand has allowed some businesses to grow quickly. Another perfume shop, for instance, opened two new branches within just two years. As the shop owner put it:

Our shop in Peshawar was doing fine. But when we moved to Kabul, within three months we were making double the profit we used to. Sales were so good we had to rent the shop next door because one shop wasn’t enough for all our customers.

This boom in IEA-friendly businesses also reflects the absence of such shops in the first days of the Emirate. At that point, there was demand, but no supply. “When a mujahed wanted to buy something like a shawl or a cap, he would have to search in many shops and often wouldn’t find what he was looking for,” one fragrance shop owner said, because during the Republic, “people [in Kabul] didn’t wear those things and there were no shops selling them.” Republic-era fashion shops in cities, for example, tended to cater to more regional fashions, including shorter and more colourful shalwar kameez for women and shalwar kameez worn with blazer jackets for men, or western suits. A tailor noted that many of his customers today are senior officials, including several deputy ministers and directors. One tailor claimed that “during the previous government, officials used to order and buy their clothes from abroad.” But, he added, “the mujahedin don’t do that. They come to shops like ours instead and that’s very helpful for businessmen.”

In the restaurant sector, interviewees said that the foods they serve have gained new customers, with many Kabul dwellers welcoming the new cuisines. One restaurant owner said that “when someone first comes and tastes the dudh patti, they soon become a regular customer.” He claimed that Afghans who have lived or travelled to Pakistan are increasingly visiting their restaurants and eating South Asian foods.

While some have found their new commercial enterprises easy, for others, adjusting to the expectations of city dwellers has been difficult. Running a business in rural Afghanistan or refugee settings in Pakistan is very different from operating in cities like Kabul, where the expectations of urban customers differ. One restaurant owner explained:

I opened a Biryani restaurant. At first, the decoration, lighting and overall look of the shop wasn’t appealing, so the Kabulis didn’t come. After a year, I rented another space and invested heavily in decoration and lighting. I chose a uniform for the waiters and ran some online advertisements. Now, praise be to Allah, customers come from all over the city – even families come and eat here.

Many have also adopted modern commercial strategies, including professional advertising and an active social media presence to enlarge their customer base. Similarly, a tailor described how his way of working had to change to meet urban expectations of professionalism:

Working in Kabul is different than in the atraf [countryside] or other provinces. For example, [in a rural area], you might tell a customer to come back the next day and your clothes will be ready, but when he came back, they weren’t ready and he’d normally go off without saying anything. But in Kabul, when you tell someone their clothes will be ready at a certain time, you should deliver them or you’ll lose that customer. They’re very sensitive and demanding.

One bakery owner also reflected on his early difficulties with the main language of the capital: “During the initial days, I didn’t speak Farsi and struggled to communicate with customers who only spoke it and didn’t understand Pashto. But later, I learned Farsi and can now speak it fluently.”

Not all experiences of business since 2021 are so positive, however. The Afghan economy contracted sharply after the fall of the Republic and has for the most part remained stagnant. There have been modest signs of economic recovery, with an estimated increase in the Gross Domestic Product of 2.5 per cent in 2024, according to the World Bank’s Development Update of April 2025, growth which, however, is not keeping up with the rise in population. The same publication warned that a widening trade deficit, combined with high unemployment, poverty and food insecurity, means the overall economic situation remains fragile. AAN’s 2024 survey of the private sector, which focused on people whose businesses predated the fall of the Republic, also heard stories of plummeting sales and downsizing.

A changed attitude towards business

What is striking among the interviews collected for this report is that former Taliban, by entering into the urban private sector, have largely adapted to an environment shaped by norms very different from those they were used to, where, for instance, business demands active engagement with worldly matters and broader society. This is a sphere from which people with a background in religious studies were previously distant, or even suspicious of.

Traditionally, the Taliban came from rural, socially conservative and economically disadvantaged backgrounds – distant from commerce, and often holding business in low regard. Even during their first rise to power in the 1990s, when they entered and lived in major Afghan cities, their ‘rural ethos’ remained largely intact. They were mullahs, madrasa students and other villagers with a conservative religious worldview who found themselves in unfamiliar urban environments and rarely engaged with city-based businesses or money-making ventures. Their focus remained on military victory and enforcing their vision of an Islamic order, with little attention paid to business and commerce. Their lifestyle was austere, grounded in simplicity and reflective of a village-based worldview with little material ambition. Later, during the insurgency, they were also known for their critique of the corruption of the Republic and its dollar economy (AAN).

What we are now witnessing is in stark contrast and appears to be a genuine transformation within the movement. Its mindset and outlook appear to be shifting at a fundamental level, moving away from their traditional roots toward a more urban-centric worldview. In this new orientation, worldly and material pursuits are embraced with a passion and intensity that mirrors many aspects of modern society.

The Taliban movement was historically dominated by mullahs, who supposedly would, in times past, reject worldly pursuits in favour of spiritual devotion, but who now appear to be developing an increasing interest in material matters.[4] IEA officials and affiliated clerics are actively seeking wealth and status, leveraging state resources and political influence to transform themselves into the new business elite.

What began as a religious movement rooted in rural values is now fully immersed not only in governing a country, but also participating in a modern trade economy. This shift towards business reflects deeper changes within the Taliban movement itself. It marks the emergence of the Taliban not only as spiritual leaders and political rulers but also as an economic elite – engaging in business and adopting lifestyles centred around what they once dismissed as worldly possessions. They are not merely participating in the attractions and pursuits of modern life – something they traditionally despised as opposed to taqwa (piety) and their spiritual role in society.

Why did the Taliban not undergo a similar transformation during their first rise to power in the 1990s? One possible reason is that the urban economy, indeed the national economy, at the time was too weak, with cities largely in ruins following years of civil war and little infrastructure to support a consumer economy. Moreover, they were still largely engaged in fighting, with even ministers often being part-time in government and part-time at the frontline.

But there is more to it. The Taliban themselves have changed. Over the past two decades, their exposure to the outside world has grown and material wealth has become a dominant value across Afghan society, especially after the flood of foreign aid and military spending that accompanied the US intervention. While the Republic was always stricken with poverty and enormous income inequalities, the cities were full of consumer goods and ostentatious displays of wealth. The most profound impact of the US-led presence in Afghanistan may not have been military or political, but cultural: a deep transformation in social values, lifestyles and aspirations. Even the Taliban, long seen as the least materialistic and most austere among the Afghan political organisations, have not been immune to that. One might say that while the US failed to defeat the Taliban militarily, the wealth and consumer economy that the US presence brought to Kabul is now winning over the Taliban members who constitute the city’s new elite – and radically changing their lifestyles. The idealistic values they once upheld have been clearly influenced by global, capitalist ones. Unsurprisingly perhaps, while the IEA moved quickly to eradicate the rampant levels of government corruption that the Republic era was notorious for, in particular customs and tax revenues (see this 2023 Alcis report), over time, allegations of corruption among its own ranks have grown, in contrast to their first Emirate (EurasiaReview, 8amMedia).[5]

A new economic elite reshaping the face of cities

What is particularly striking is the rise of a new Taliban economic elite, whom these businesses both serve and enable. Just as in the Republic period – when high-end businesses in areas like Shahr-e Naw and Wazir Akbar Khan were popular with the Republic’s political elites – these same neighbourhoods are now trying to adjust to serve and attract the newly emerging Emirate elite. Back then, these areas were full of expensive restaurants, cafés, boutiques and shops offering luxury goods and services. Now, they cater to the Emirate’s rising class.

Senior Emirate officials – from ministers and deputy ministers to other high-ranking figures – now frequent these businesses. During occasions like Eid, when high-level Taliban presence in these districts increases, the Emirate imposes tight security measures to prevent any incidents. This shift is perhaps best illustrated by a shop owner who sells natural products in Kabul’s Qalah-e Fathullah. He recalled:

We lost most of our customers in the first years of the Taliban as they had mostly been officials from the Republic, foreigners or people from NGOs. But now, I’ve gained new customers from the Taliban. They’re just like the old officials. Before, two Land Cruisers would show up and men in suits and ties would come in and spend a lot of money on my products. Now, the same Land Cruisers arrive, but men in turbans buy the exact same things.

The shopkeeper observes a divide between those tempted by luxury goods and their former comrades:

It’s easy to tell the difference between a true mujahed and someone who’s fallen into the trap of worldly comfort. The second type wears a silk turban, an Al-Fajr watch [which reminds you of prayer times], Skecher shoes, a sandalwood tasbih [prayer beads] and carries an iPhone 16. But real mujahedin are still struggling to meet even their basic needs.

The desertion – or loosening – of previously-held standards of austerity by rebel movements, once they have seized power, has been constantly reported by chroniclers throughout history, as has the dichotomy in their ranks between those who remain zealously faithful to the pristine ideals and those who take advantage of the newly-acquired power. In the case of Afghanistan today, this phenomenon is certainly shaped by the gap between rural areas, where limited development means life has remained simpler and therefore closer to Taliban principles, and the major cities, where modernity and wealth have increased opportunities and economic divides. In the cities, one can see how swiftly the Taliban – once critical of their opponents for chasing wealth and privilege – are now, much like previous governments, adopting the same elite lifestyles as those they took power from. More broadly, these changes raise important questions about how, in today’s world, power, wealth and modern life can quickly reshape and influence even rigidly ideological movements like the Taliban.

Aside from these internal changes, the Taliban’s growing role in business has also changed the appearance of Kabul and other cities. Over the past 20 years, Kabul had developed into a diverse, modern city with a range of regional and international influences. Many shops, restaurants, snooker clubs and coffee shops had Western-style names, designs and menus.

Since the Taliban returned to power, that Western influence is fading. The new businesses tend to follow Gulf or Pakistani styles, where many Taliban members lived in exile. While those influences have long been present as well, particularly in architecture, one can see this clearly increasing in areas like Shahr-e Naw and Wazir Akbar Khan, where many of the new businesses use Arabic or Pakistani names and signs, like Quetta Tea and Biryani or Al-Hidaya Tailor.

Still, for the most part, these aesthetic changes have not come from intentional government intervention. The Emirate has done little to directly shape the city’s look or culture. One step they did take was setting up a commission to standardise shop signs, which introduced a rule saying all signs must be in Pashto or Dari, and banned foreign languages, particularly English. There have also been efforts to remove human imagery such as mannequins’ heads and images of women in advertising, as well as to reduce the visibility of feminine consumer goods and beauty salons (NPR, Al Jazeera).

A more inclusive economy, or elite inverted?

The appearance of a new class of businessmen is a reversal of the situation under the Republic era. To Taliban members and some rural residents, particularly Pashtuns who supported the Taliban and were unable to do business in the cities, the economy under the Islamic Emirate feels more inclusive. Interviewees argued that for two decades, they had been unable to engage in business in the cities, both because of insecurity and the Republic’s attitude toward them. They also noted that they were excluded from participation in government and that development projects were not implemented in their areas. In making these arguments they tend to overlook Taliban policies, as the group prohibited people from taking government or NGO jobs and often obstructed development initiatives, something that changed after the takeover (though there are still restrictions on NGOs, particularly for women).[6]

Interviewees tend to frame the current shift as a correction to past inequities. Now, they say, men from rural areas engage in business in urban centres, hold government positions and benefit from development projects directed toward their communities. Of course, the benefits are not accruing to people from all rural areas – rather those regions that supported the insurgency – and it is limited to men, rather than encompassing women as well. One interviewee, an IEA official, expressed this sentiment bluntly:

Everything in the last two decades was for people living in the city. They had electricity, schools, hospitals and jobs. Nothing happened in the rural areas as if they weren’t part of the country. We had no jobs and no right to do business; we were only being killed and arrested.

A Taliban supporter from Logar province also noted:

For rural people and for Afghans in general, the Americans and the Republic didn’t bring much. The money they brought went into their own pockets and those of their puppets. For ordinary people, there was nothing except bombs and raids. We didn’t even have the right to breathe, let alone benefit from what they called services and opportunities.

According to such views, the Emirate has helped level the economic field. The claim is that economic and public services are now more equitably distributed. One person explained:

Praise be to Allah, now people from all parts of the country have equal rights and access to economic opportunities. In the past, a man from sahra [rural areas] couldn’t open a shop in the city, but now he can do so without any problem. A man with a beard couldn’t easily get a job before, but now he can. This means we were excluded and weren’t given a chance to participate in economic life. But now, we’re free.

However, this narrative still raises the question of whether, in reversing past exclusions, a new set of exclusions has emerged under Emirate. While Taliban supporters deny this, arguing that there is no systematic economic favouritism, it is evident that the composition of the economic elite and indeed, the business class has shifted significantly. For many Afghans who were poor urbanites or indeed poor people in the countryside during the Republic and remain so now, the idea that the Emirate is more inclusive may seem risible.

It is difficult to fully assess the extent to which businesses in Kabul have been affected, but it is clear that certain sectors are in decline, some because of the economic contraction, others as a direct result of Emirate policies. For example, some leisure businesses such as cinemas and video arcades were banned, restrictions on private media companies, particularly bans on music and drama, forced many to close, while restrictions, including on women working, led to the closure of many NGOs, many of which were effectively small businesses (AmuTV, AlJazeera).

The biggest blow to some of these enterprises comes from the IEA’s restrictive policies on women. This has raised significant barriers for women in public life, including women-owned businesses, which have suffered more since the August 2021 takeover than their male-owned counterparts (see World Bank surveys of the private sector, for example from February 2024). There have been attempts to manage the restrictions, with some women managing to run small home-based businesses (France 24). Other attempts at working around segregation and movement restrictions have failed (see for example this report from UNHCR). The IEA’s restrictions also affected businesses that relied on female customers. For example, one park owner told the author: “In the past, my park’s primary visitors were families, but since the Taliban banned women from going to parks, I have lost most of my customers and am now operating at a loss.” Women’s beauty salons have also largely been forcibly shut by the IEA (BBC). Others businesses are affected by the broader morality policy of IEA’s Ministry for Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. For instance, a hookah shop owner in Kabul, who had invested about USD 50,000 in his business, explained that IEA restrictions had caused him significant financial damage. Although apart from Kandahar and Herat, the Emirate’s official policy on hookahs is ambiguous, the shop owner said, “We’re no longer allowed to serve hookahs” (Radio Azadi, DW).

Another indirect impact comes from the departure of the former Afghan elites and Westerners who once constituted an important segment of the customer base for many businesses. For instance, the antique shops in Shahr-e Naw, once frequented by Western tourists, diplomats and NGO workers, have seen a sharp drop in business since the Taliban takeover, largely because their customer base has vanished as many foreigners and wealthy Republic officials left with the takeover.

Conclusion

The last two decades have reshaped Afghan society in profound and often unexpected ways. These shifts have extended even to the most conservative segments of the population, including the mullahs and the Taliban. In the past, religious figures often lived outside the private sector, sustaining themselves through community support, endowments and public donations. Today, however, many are increasingly integrated into the urban market economy, establishing and managing businesses across different sectors. This economic engagement is not merely a matter of livelihood but also a reflection of how social and cultural norms in Afghanistan are being renegotiated.

For the Taliban and their supporters, taking part in business brings not only income but also a sense of acceptance in society, after years of feeling marginalised in their own country. Previous Afghan governments have relied upon political-military and economic prominence, usually backed-up by some degree of external support. The IEA might have lost much of the external support, but has it added to the formula of power a virtually unquestioned religious authority. For the first time in Afghanistan’s modern history, religious authority is aligned with political control and economic activity and these spheres are becoming interconnected in Afghan society.

This represents a boost for the Taliban grasp on power, but it could also trigger a backlash. The sight of the new Taliban business elite, thriving in their new urban lives, may not endear the IEA to some of their citizens, especially at a time when so many Afghans experience acute economic hardships.

Edited by Fabrizio Foschini and Rachel Reid

References

| ↑1 | See Shoaib Sharifi and Louise Adamou, Taliban threaten 70% of Afghanistan, BBC finds, 31 January 2018, BBC. AAN’s Kate Clark was asked to review the research before publication. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a fascinating insight into how business, insurgency and the frontlines intersected, see Fazl Rahman Muzhary , Finding Business Opportunity in Conflict: Shopkeepers, Taleban and the political economy of Andar district, 2 December 2015, AAN: “[W]hen frontlines shift and military masters change – due to insurgency, uprising or rising government power – how can shopkeepers react to try to survive the situation? Indeed, how can they try to find benefit or manipulate frontlines and road closures to their advantage?” |

| ↑3 | See AAN’s 2014 dossier of reports, Detentions in Afghanistan; see also Open Society Foundations’ Strangers at the Door: Night Raids by International Forces Lose Afghan Hearts and Minds, February 2010. |

| ↑4 | For more details on the mullahs’ transformation towards business, see Sharif Akram, Living a Mullah’s Life (1): The changing role and socio-economic status of Afghanistan’s village clerics, Afghanistan Analysts Network, 2025. |

| ↑5 | An AAN examination of Taliban expenditure in 2023, while acknowledging a dramatic drop in areas such as customs corruption, raised concerns about the lack of clarity about the expenditure of revenue raised. |

| ↑6 | For a 2023 report on better economic times for those living in areas that had been ‘insurgent strongholds’, see this AAN report Finding Business Opportunity after Conflict: Shopkeepers, civil servants and farmers in Andar district by Sabawoon Samim. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign