Abdullah, a 37-year-old father of four, from eastern Afghanistan, was evacuated in late August 2021, via Kuwait and Spain, to a military camp in Virginia and from there to Houston, Texas. He entered the US on humanitarian parole under President Joe Biden’s programme, “Operation Allies Welcome.”[1] Abdullah, who previously worked at the Election Commission and Ministry of Education under a USAID contract, left Afghanistan on his own, leaving his wife and four children with his parents. He has not seen them now for almost four years. When AAN interviewed him in March 2025, despite the Trump orders, he was still hopeful that they would be reunited:

They told me I cannot get reunification with my family before my asylum application gets approved. I got asylum in February 2023 and immediately applied for reunification. It’s been in process since then. I still hope my family will be evacuated. I want them out of Afghanistan as soon as possible.

Still, after Executive Order 14163, which paused all refugee processing, including family reunification, it looks unlikely that he will be able to bring them to the US any time soon. He would lose his asylum status if he went to Afghanistan to see them, so he would need to arrange to meet them in a third country. This, though, might change if he obtains a green card.

Abdullah is one of about 200,000 Afghans who sought safety in the US after the fall of the Islamic Republic in August 2021 and one of many whose family members might now be left behind for the long term, after a series of changes in the US migration and admission policy introduced by President Trump’s administration in January 2025. In this report, we provide a brief overview of these changes; estimate the size of the Afghan immigrant community in the US and the number of Afghans who were resettled in the US before the policy changes. We also hear more accounts from Afghans, like Abdullah now in Texas, about how the Trump presidency has affected their prospects in the US and how they view their future.

The executive orders

On his first day in office, President Trump signed four executive orders that have a direct or indirect impact on US migration policies and refugee admissions – see below. Since then, on 12 May, the Department of Homeland Security confirmed that Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Afghans was to expire on 20 May and the programme would be eliminated as of 14 July.

1. Executive Order 14163 of 20 January, Realigning the United States Refugee Admissions Program, paused all refugee processing and travel globally. Admissions of all refugees, including the various categories under the United States Refugee Admission Program and Family Reunification cases, were paused.

2. Executive Order 14169 of 20 January, Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid, paused all foreign aid. This had a direct impact on the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) programme, created in 2006, which provides a pathway to legal permanent residency (also known as getting a green card) for Afghan and Iraqi translators and interpreters employed by the US military (more detailed explanation below). The order did not directly pause this programme but it shut down the support services that enable it to work.

3. Executive Order 14165 of 20 January, Securing Our Borders, seeks to secure the US southern border by increasing physical barriers, deploying additional military and homeland security personnel and expanding detention and removal operations. It also reinstated the Migrant Protection Protocols, under which the US government can return foreign individuals entering or seeking admission to enter the US from Mexico. It also restricts the use of categorical parole, a programme where individuals are considered for parole based on their membership in a specific group or category, rather than their circumstances. Finally, it prioritises the prosecution of immigration-related offences.

Following this order, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) announced that it would pause its humanitarian parole programme. Humanitarian parole allowed people to temporarily enter the US due to urgent humanitarian reasons. This allowed for the admission into the US of Afghans, like Abdullah, whose story began this report. The pause in granting humanitarian paroles prevented Afghans still hoping to get to the US, among others, from requesting it. Also, however, the thousands of Afghan parolees already relocated to the US faced their parole being terminated. Some received notices of ‘intent to remove’ – meaning – deport, within seven days, despite ongoing asylum claims or work authorisations (The AfghanEvac).

4. Executive Order 14161 of 20 January, Protecting the United States from Foreign Terrorists and other National Security and Public Safety Threats, directs federal agencies to enhance immigration screening and vetting procedures to prevent the entry of individuals who may pose a “terrorist, national security, or public safety threat” to the United States. Sometimes referred to as the ‘extreme vetting’ order, it also calls for reviews that may lead to travel bans or restrictions, as well as enforcement actions. Should Afghanistan be included on the list of countries for which vetting and screening information is deemed insufficient, even Afghans who have US Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) in their passports and were on their way, as they thought, to the US, could be denied entry into the country. However, it seems a new travel ban has been postponed; the State Department has said it was working on a report that would serve as the basis for restricting visas, the original deadline of 21 March was no longer in effect and it was unable to say when the report would be ready. People are now waiting to see what the State Department’s report will mandate and which nationalities it might ban.

5. Termination of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Afghans on 12 May. This programme provided temporary legal status and the pathway to apply for work authorisation to nationals from specified countries experiencing armed conflict, natural disasters or other extraordinary conditions. President Biden designated nationals from Afghanistan as having TPS following the Taliban’s takeover in 2021 and most of the tens of thousands of Afghans evacuated to the US were first given humanitarian parole and when that expired, given the Temporary Protected Status (Politico).

Already in April this year, the Department of Homeland Security had decided not to renew expiring temporary protections for thousands of Afghans living in the United States, raising concerns about the future of Afghanistan’s designation as a TPS (Al Jazeera, NPR). Then, on 12 May, Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem said that the TPS designation for Afghans would have expired on 20 May and the programme would be terminated on 14 July.[2] “This administration is returning TPS to its original temporary intent,” she said. “We’ve reviewed the conditions in Afghanistan with our interagency partners and they do not meet the requirements for a TPS designation. Afghanistan has had an improved security situation and its stabilising economy no longer prevents them from returning to their home country.”

Approximately 10,000 Afghans are potentially affected by this decision (The New York Times), although some among them may have other pathways to stay in the country. This might be a valid work authorisation, for example, or an asylum claim – although very few asylum applications are eventually approved and cases can often take several years to get resolved either way. President Trump recently personally took aim at the asylum system, The New York Timesreported, on 21 May. “In April, the Justice Department urged immigration judges to swiftly deny asylum to immigrants whose applications they deemed unlikely to succeed. That month, the newspaper said, the denial rate, which “was already trending upward, rose to 79 percent.”

How many Afghans are in the US?

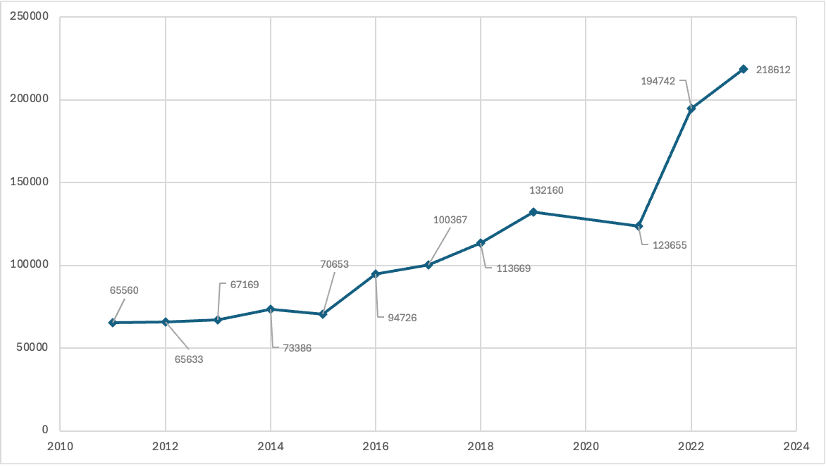

There has been an Afghan immigrant population – people who have legal residential or citizenship status in the US who are of Afghan origin or descent – in the US since the 1978 Saur Revolution drove members of the Afghan elite out of the country. However, the Afghan community has experienced rapid growth in the last 15 years. Even before the Taliban’s capture of power, the population had nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020, increasing from 65,000 to 132,000 individuals (See Graph 1 below). According to an analysis by the US-based think tank, the Migration Policy Institute, “this substantial increase can be attributed to years of war and political instability in Afghanistan that generated a steady flow of humanitarian migrants.” The fact that there was an easy and legal way for Afghans to go directly to the US under Special Immigrant Visas (see below) also helped swell numbers. The Afghan immigrant population swelled further after the re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate, reaching, by 2024, almost 220,000 US citizens or permanent residents of Afghan origin.

Graph by AAN.

There are many more Afghans in the US who do not yet have a settled status. Some are among the more than 200,000 who arrived in the United States since the fall of the Islamic Republic. It is difficult to provide an exact number because there are several legal pathways into the US and how people are counted varies between the different government entities collecting statistics. Some of the numbers, which may or may not overlap, are: more than 117,000 Afghans who are Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) holders or humanitarian parolees have arrived since 2021, according to the US Refugee Processing Centre report for the fiscal year 2024 (PRC’s Report to the US Congress); the US Congress reported that nearly 150,000 Afghans were resettled between August 2021 and August 2024; over 82,000 Afghans were evacuated in the last two weeks of August 2021, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s Operation Allies Welcome Afghan Evacuee Report of whom, 76,000 were granted humanitarian parole and subsequently Temporary Protected Status upon their arrival in the US (DHS).

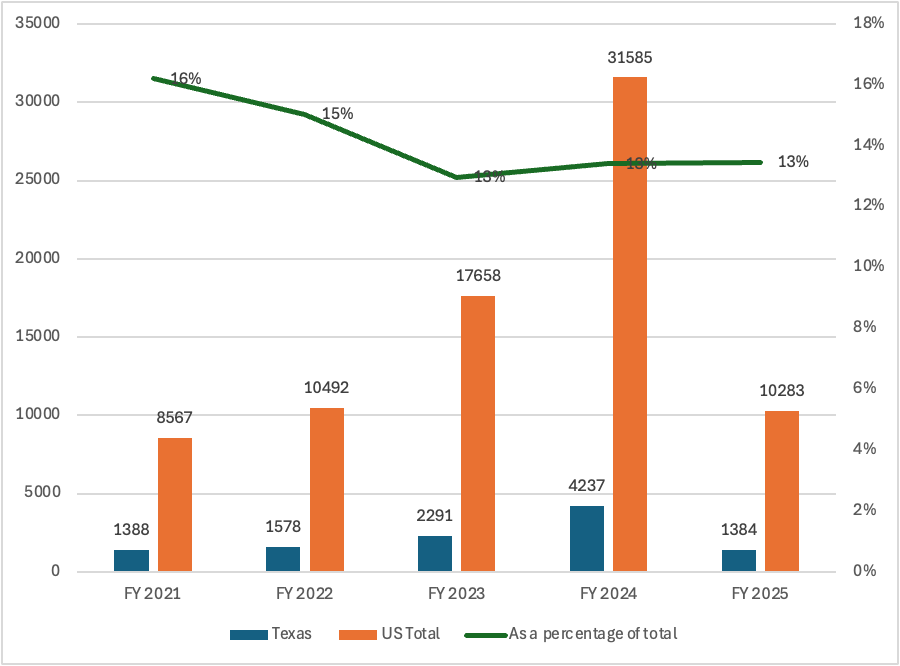

Another way of breaking down the numbers is to look at how Afghans entered the US: since 2021, they have pursued three avenues – humanitarian parole, the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) programme and the United States Refugee Admission Programme (USRAP). The Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) programme, created in 2006, originally issued a maximum of 50 SIVs per fiscal year, but it has been extended and amended multiple times to increase the threshold (the Afghan Allies Protection Act of 2009 expanded eligibility to include any Afghan national employed by the US government). According to the Refugee Processing Centre annual reports, a total of 78,585 Afghans with SIV status arrived in the US between October 2020 and December 2025 (see the Graph 2 below). Of this number, 10,878 Afghans with SIV status came to Texas, or 14 per cent of all SIV arrivals in the US (Refugee Processing Centre ).

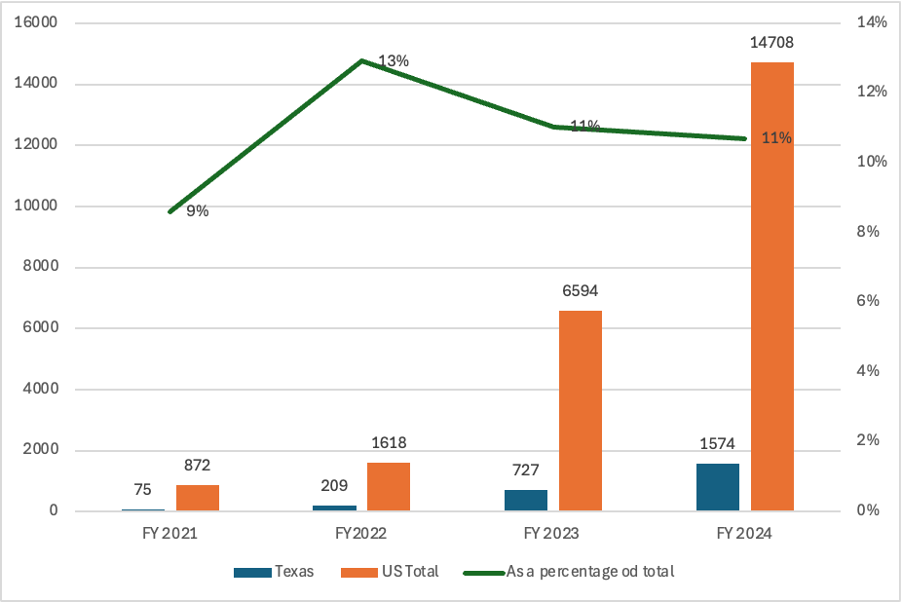

The United States Refugee Admission Programme (USRAP) is the legal pathway for the resettlement of individuals regarded as refugees under US law. They are allowed to work in that first year and must apply for permanent residency (a green card) one year after arriving. According to the Refugee Processing Centre’s data, a total of 23,792 Afghan refugees were admitted to the US between October 2020 and September 2024 (see Graph 3 below).[3] Of these, 11 per cent or 2,585 Afghans were sent to Texas.

However, most Afghans evacuated to the United States after the 2021 withdrawal came to the US on humanitarian parole, which gives only temporary permission to stay in the country and no direct legal pathway to a green card. Congress has repeatedly declined to pass legislation allowing Afghan parolees to apply for permanent legal status, or to allow them to become eligible for an SIV status (Migration Policy Institute).

Who are the Afghans in Texas?

After the collapse of the Republic, Texas received more Afghans than any other state – almost 15 per cent of those who arrived – with more than 15,000 now resettled there. Nearly half were sent to Houston, followed by Dallas-Fort Worth and San Antonio and with the smallest number sent to Austin. A former worker with the Refugee Service of Texas (RST),[4] an organisation that has helped over 2,000 Afghans resettle in this southern state, said they mainly worked with Afghans who came on SIVs. She explained why so many Afghans had come to Texas:

There is a huge military presence in Texas and so there was a lot of advocacy to get the SIVs out of Afghanistan. Most had [already] spent around several years getting fully vetted and getting that status, the SIV status. … They’d served as translators, cooks, drivers for our military and they were promised protection for themselves and their families. They were promised protection.

She said the Refugee Service of Texas worked with Afghans in the major cities, providing them with three months of initial support and then an additional nine months as they get on their way to self-sufficiency. However, that all changed, the worker explained, after Trump’s Order 14163 paused all refugee processing and travel globally, including family reunification.

It’s a huge injustice. They feel a huge injustice that some of them didn’t get their whole families out. Some of them don’t have a track for permanent residency. They’re somewhat in that limbo state, similar to Temporary Protected Status – TPS.

The NGOs working on refugee resettlement were also hit when the Trump’s administration suspended their funding (CBS, AP). This has had a ripple effect on smaller NGOs, one worker said: “We were denied a grant recently and I can’t really figure out why … The decision [not to fund us] was made after Trump came into office.”

She believed many people in decision-making positions now think that “this refugee thing has stopped … because there is no one arriving,” but “because of that and because of the loss of funds, there are going to be all these people who fall through the cracks. … It really is wretched. It’s wretched where people have been left.”

The Afghans AAN spoke to confirmed with their own personal stories how much worse the situation has become since January.

Aftab, a 35-year-old from central Afghanistan and holder of an SIV, was the most recent arrival among AAN’s interviewees. He had first flown from Kabul to Germany, where he and his family stayed for 26 days while their documents were being processed. When they came to the US, they initially landed in New York and were then sent to Houston via Atlanta, Georgia. But although his case had been processed well in advance and his SIV status approved, he said the process is now lagging:

I have an SIV and don’t yet have a green card. I applied for the green card when I was in Germany and they told us that it would arrive three months after we did. However, I haven’t received it, yet. My wife and child are with me in the US, while the rest of my family is in Afghanistan. I have no plans for those left behind, as I’m currently waiting for my own documents.

After landing on 11 December 2024, he was given kitchen items and furniture, as well as three months of free rent. That was far less than his compatriots who had arrived a year earlier. Other help had stopped completely by March 2025, when we interviewed him, as he explained:

The agency was also paying me a check of 200 dollars per family member. However, they’ve now cut that. My friends who arrived a year ago received rent assistance for six months and cash assistance for another six months.

When asked about the impact of Trump’s orders on him, he said:

I now have no access to the cash assistance that is my right. I hope it will resume soon. In the past, my friends received various kinds of support from the resettlement agencies, but now I don’t receive any support. We don’t receive support from the resettlement agency because many of its employees were laid off after the orders from the new president.

Aslam Khan, a 38-year-old from southern Afghanistan, left the country as the Republic was collapsing. He was granted humanitarian parole upon his arrival in the US and when this expired, he applied for Temporary Protected Status. He recalls his journey out of Afghanistan:

When the government was on the verge of collapse, the directors and bureau chiefs of American agencies instructed their staff to get to the airport. I went, along with my four children and wife. We were waiting there for two days, [then] in the evening of the second day, we went home. The next day, when we returned to the airport, we were allowed to board a military plane and headed to Doha.

The family stayed in Doha for three days before being taken to the US, landing in Washington DC on 21 August 2021, from where they were taken to a military camp, where they stayed for 37 days. They were given humanitarian parole and sent to a resettlement agency in Houston.

The agency rented a house for me, purchased furniture and all the other necessary items for my home. Additionally, I received rent assistance for six months. The agency helped me obtain state benefits such as Medicaid [healthcare] and food stamps. The food stamps were issued for six months, while the Medicaid was provided for one year. I found a job and eventually bought a car for my family, starting my new life here. Now, I am very happy that my daughters are going to school and that we are physically safe. We enjoy both protection and freedom. Currently, I still receive Medicaid and food stamps.

He applied for asylum two years ago, but his is also still pending:

I don’t know why they haven’t granted me approval [yet]. I have no information on the matter. Whenever I ask, they tell me my asylum is pending. It’s not only my family; other Afghan families have also not received their asylum. I can’t apply for a green card before I get that approval.

Aslam Khan’s prospects also suffered after he and his wife lost their jobs when Trump’s orders meant the funding for the resettlement agency that employed them was cut. Despite everything, Aslam Khan is still positive about the future. “The plan is to wait for my documents and once I receive them, I will be sure to continue my life here in the US. I hope my children will receive a better education here. I hope we can have our own house and business in the near future to enjoy our lives.”

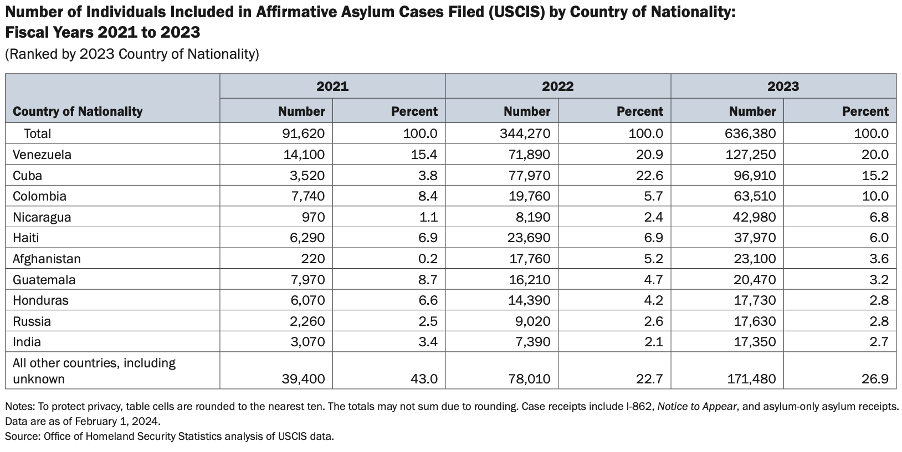

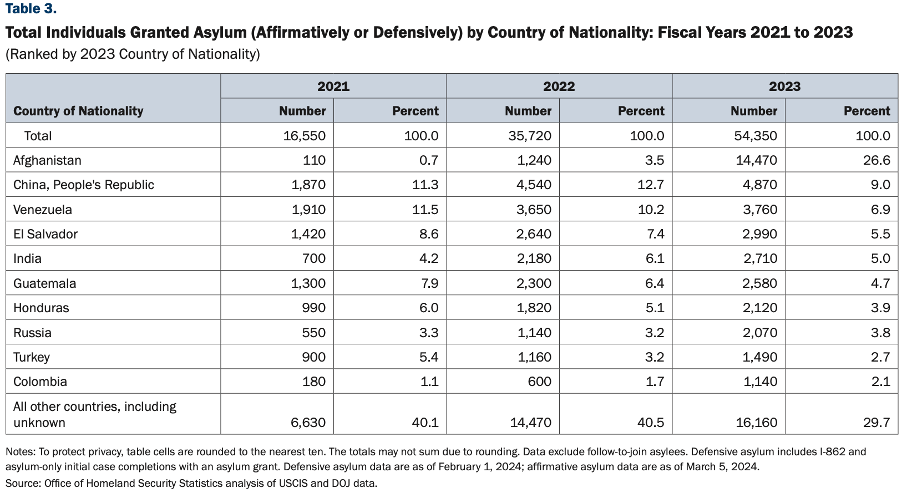

He is not alone among the Afghans left waiting on their asylum decisions in Texas. As to the numbers waiting to see if there asylum application have been approved, the tables below, from the Department of Homeland Security’s annual flow report Asylees: 2023 show that while 41,080 Afghans applied for asylum between 1 October 2020 and 30 September 2023, only 15,820 asylums were granted to Afghans.

Abdul Sabor, a 41-year-old from southeastern Afghanistan, arrived in the United States on 31 August 2021, immediately after the former government was toppled. His entire family moved together, including his brothers, sisters and mother. He recalled:

I came with a group of colleagues, most of whom worked in the media. I landed in Houston, Texas [and] the resettlement agency rented a hotel for us. [We] all stayed in the same hotel for 30 days. By the end of September 2021, almost every family had been assisted in renting a house and each family moved into their own apartment. Since then, I’ve lived in the same apartment and have never moved anywhere else. I received shelter support because the government provided me with cash that I used to pay the rent… Additionally, the resettlement agency assisted my family in obtaining food and medical assistance… I received food stamps, which enabled me to buy food for my family for a year and a half.

He said that after he got a job and started earning a living, he stopped receiving food stamps. He and his wife got private insurance through Obama Care, but his children still have Medicaid. This is now the only government support he gets: “I no longer receive rent assistance or food stamps because I can earn enough money to meet those needs.”

Abdul Sabor received asylum approval in September 2024 and, after waiting for a few more months – as advised by his attorneys – will now apply for a green card, which will give him residency.

I have applied for a [refugee] travel document, that would allow me to travel outside the United States. However, I haven’t yet received it. Furthermore, even if I do get it, I may not be able to travel outside the US unless I become a US citizen. I’m unable to address my property ownership issues with my [business] partners in Turkey. I’d planned to travel to Turkey to meet my property partners, but now I can’t travel, even if I receive the travel document. My only plan is to stay here in the US and refrain from travelling until I obtain my citizenship.

A way ahead for Afghans in America?

Many Afghans saw the United States – despite its many flaws – as their most steadfast ally throughout the Republic – consistently spending more money and sending more troops than any other nation. It left many with a sense that Afghanistan mattered to the United States. It was no surprise, then, that many held out for the chance to get to the United States, even when other options were open to them, with a notion of Afghan exceptionalism added to the wider allure of America that attracts migrants from all over the world. US President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant policies have come as a rude awakening, with Afghans among some of the first migrant communities whose protections appear to have been downgraded.

While researching for this report in Texas in March 2025, AAN approached many Afghans currently living there. Many politely refused to speak. Some said they had nothing to say and that they are living a good life in the US. Others were clearly afraid to share their worries about their uncertain future. They were probably right to stay quiet. A few weeks later, on 12 May, those in the US on Temporary Protected Status are now worried they may be deported as they apparently no longer have legal grounds to stay in the US. In whichever direction the US migration and refugee admission policy goes in the future, for Afghans at least, the operation to welcome them as allies is well and truly over.

Edited by Kate Clark and Rachel Reid

References

| ↑1 | Operation Allies Welcome was launched on 29 August 2021 when President Biden directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to “lead and coordinate ongoing efforts across the federal government to support vulnerable Afghans, including those who worked alongside us in Afghanistan for the past two decades, as they safely resettle in the United States.” Under this directive most Afghan that had been evacuated were paroled into the United States on a case-by-case basis, for humanitarian reasons, for a period of two years. In summer 2021, the Department of State also set up the Afghanistan Task Force (ATF) to address the most pressing priorities of the time (State Magazine). This task force was transformed into the Office of the Coordinator for Afghan Relocation Efforts (CARE), in November 2024 (US Congress, State Magazine), which Trump ordered to be closed by April 2025. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See an op-ed published in an online policy journal ‘Just Security’ by Hanifa Girowal, Ambassador Melanne Verveer and Kimberly Hart Removing Protected Status for Afghans in the U.S. is No Way to Treat Allies. They wrote:

If TPS is fully terminated on July 14, thousands of Afghan allies will be left out in the cold. Some won’t qualify for other forms of legal protections, such as special immigrant visas (SIVs) or asylum status – because of the criteria for these protections. Others may be deported before they can complete the slow and challenging legal process of attaining longer-term protections plus data on threats. Deporting allies isn’t only an unjustified bureaucratic decision. It is a betrayal. It should be reversed and TPS should be extended, before more Afghans suffer and die at the hands of the Taliban. See also this NPR report and this Radio Free Europe report. |

| ↑3 | A total of 11,454 persons were admitted to the United States as refugees during 2021, including 4,557 as principal refugees (granted refugee status in their own right) and 6,897 as derivative refugees (a family member – spouse or child, granted refugee status based on their relationship to the principal refugee). In 2021, the leading nationalities for individuals admitted as refugees were the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (43 per cent), Syria (11 per cent), Afghanistan (7.6 per cent), Ukraine (7 per cent) and Burma (6.7 per cent). See the Department of Homeland Security annual flow report, Refugees and Asylees: 2021.

In the following year, 2022, a total of 25,519 persons were admitted as refugees, including 9,012 as principal refugees and 16,507 as derivative accompanying refugees. In 2022, the leading countries of nationality for individuals admitted as refugees were the Democratic Republic of the Congo (30 per cent), Syria (18 per cent), Burma (8.4 per cent), Sudan (6.5 per cent), and Afghanistan (6.3 per cent). See the Department of Homeland Security annual flow report, Refugees and Asylees: 2022. In 2023, the number had risen, sharply: a total of 60,050 persons were admitted as refugees, including 21,760 as principal refugees and 38,290 as derivative accompanying refugees. The leading nationalities that year were the DRC (30 per cent), Syria (18 per cent), Afghanistan (11 per cent) and Burma (10 per cent). See the Department of Homeland Security annual flow report, Refugees: 2023. |

| ↑4 | According to their website “Refugee Services of Texas is a social-service agency dedicated to providing assistance to refugees and other displaced persons fleeing persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group, as well as to the communities that welcome them.” It was founded in 1978. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign