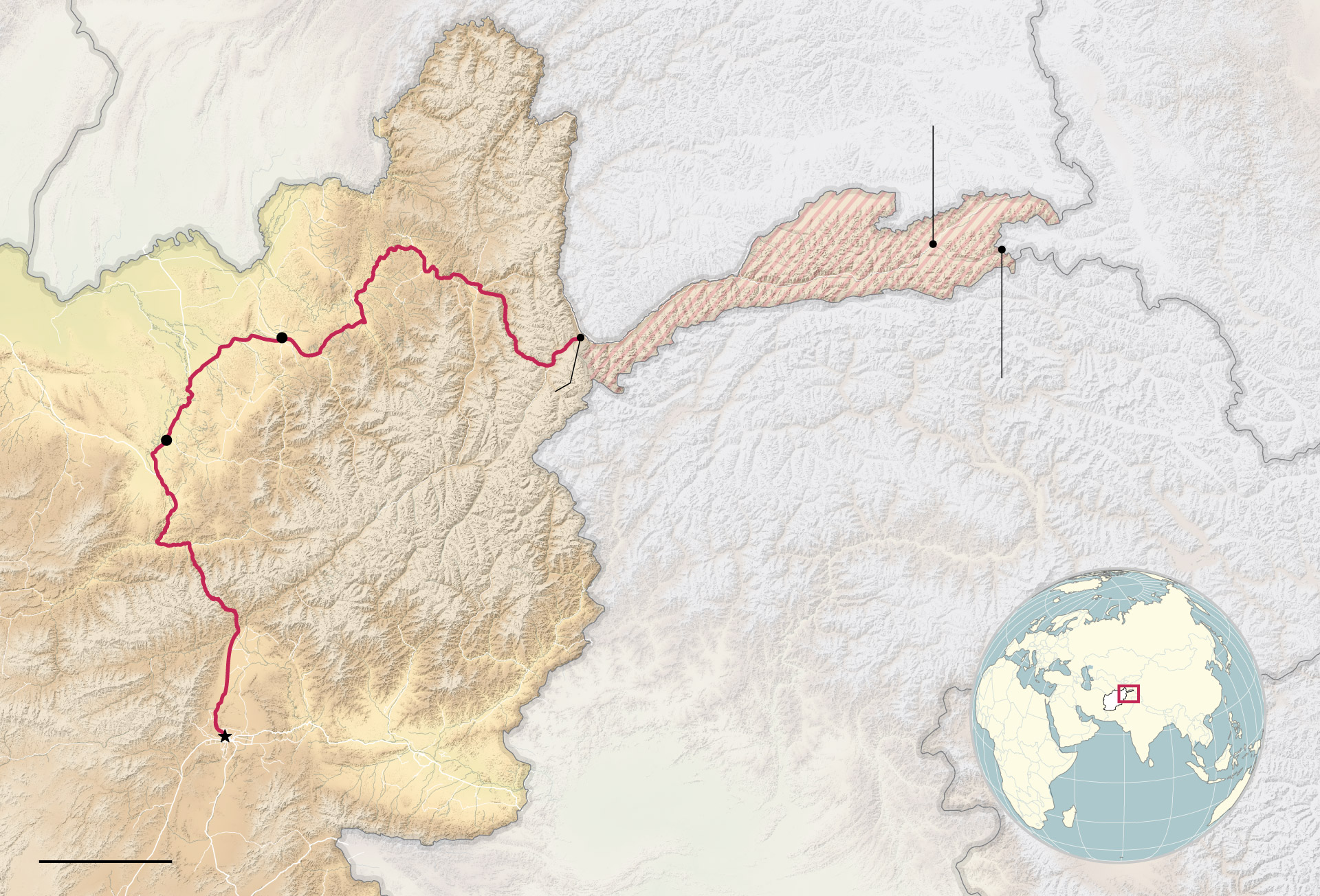

Taliban officials have a plan to turn one of the country’s remotest corners into a global trade hub by linking the Afghan heartland with China.

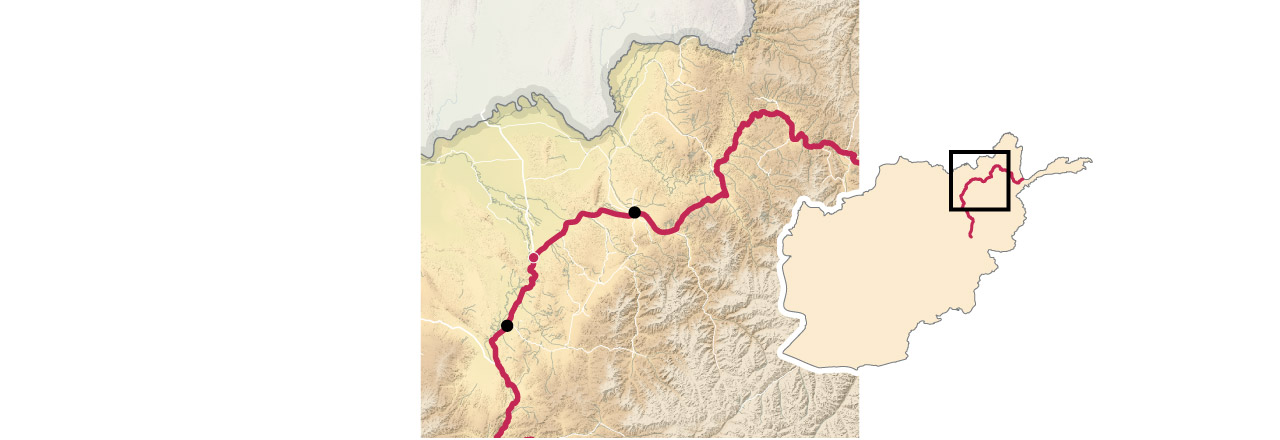

If the road is ever completed, it would bypass Pakistan, dramatically cutting travel times between Central Asia and China and potentially promoting trade in rare minerals and other resources, such as lithium, cobalt and gold. The highway’s boosters see it returning Afghanistan to the central place it held ages ago on the Silk Road, as China pushes forward with plans to build a modern version of the route with an intercontinental network of land and maritime routes. “Wakhan is part of it,” said Abdul Salam Jawad, a spokesman for the Taliban-run Ministry of Industry and Commerce.

Buzai Gumbad

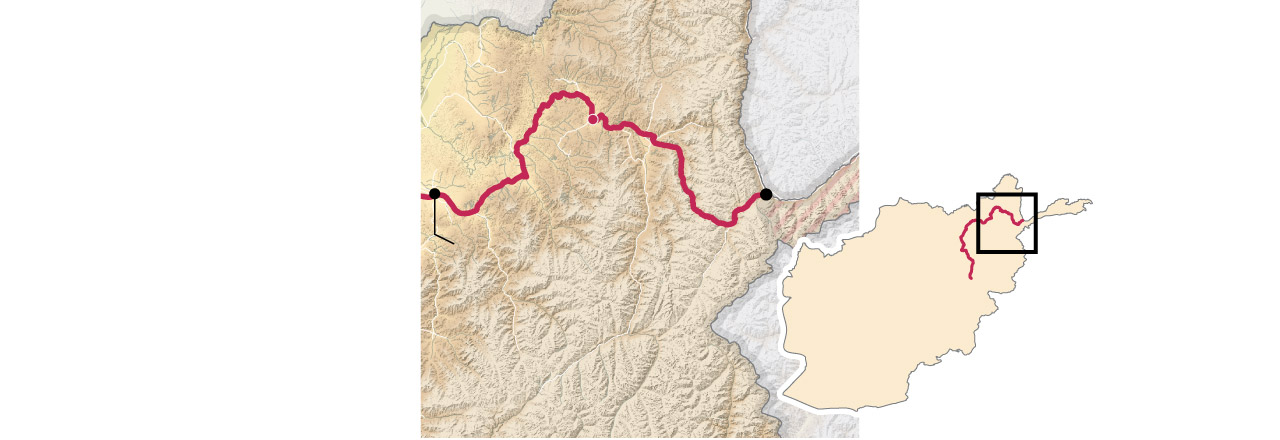

The Taliban says its initial task is to pave a 30-mile stretch of dirt road just west of the Chinese border, though 200 more miles are also largely unpaved and badly in need of improvement. Ultimately, the route will require building durable bridges and eliminating river crossings that become inaccessible in high water.

But its detractors say the road could easily become a highway to nowhere.

Satellite images from Maxar, a commercial imaging firm, show that on the Afghan side of the border, no new construction has occurred on the corridor’s Wakhjir Pass since August and that the completed segment ends in rough terrain, less than a half-mile from the border.

“Our government doesn’t have enough budget,” Zabihullah Amiri, director of the provincial Information Ministry, acknowledged in an interview. “We hope that China will help.”

The challenges facing the project are the same as those confronting the Afghan economy as a whole. The Taliban’s tightening restrictions on women and girls have left Afghanistan economically isolated, with many foreign governments, multinational companies and international agencies reluctant to invest under these repressive conditions. Security also remains a grave concern for development amid persistent attacks by Islamist militants, at times targeting Chinese visitors.

Along with a team of Washington Post journalists, I recently traveled from the capital, Kabul — 600 miles from the Chinese border — to the Wakhan Corridor to explore the factors afflicting the highway project and the Taliban’s broader aspirations.

But Afghan state media has focused instead on even the tiniest progress on the Afghan side.

In Kabul, the headlines about such progress have prompted enthusiasm. Abdul Jabar Saqib, 39, is preparing for what he projects will be an influx of Chinese merchants. He just opened a Chinese restaurant in downtown Kabul and is planning branches elsewhere in the city. Visitors arriving at Kabul’s airport, meanwhile, are greeted these days by a billboard advertising a recently opened Chinese hotel.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, the acting interior minister, recently met with the Chinese ambassador to discuss the Wakhan Corridor and “the enhancement of trade relations,” said Abdul Mateen Qani, a spokesman for the ministry.

So far, demand appears to be primarily driven by companies that can afford to take risks. Some long-standing Chinese merchants, however, say the number of Chinese people starting businesses in Kabul has actually declined since the Taliban takeover, with some citing concerns over the safety of their investments.

A language teacher in Kabul said an initial wave of interest in learning Chinese may already be fading. There is no shortage of work for the limited pool of well-qualified interpreters. But the teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing Chinese funding, said scholarship applications to study in China are being rejected en masse by the Chinese government. Only a few Chinese construction companies have shown interest in recruiting entry-level graduates for road construction or mining projects.

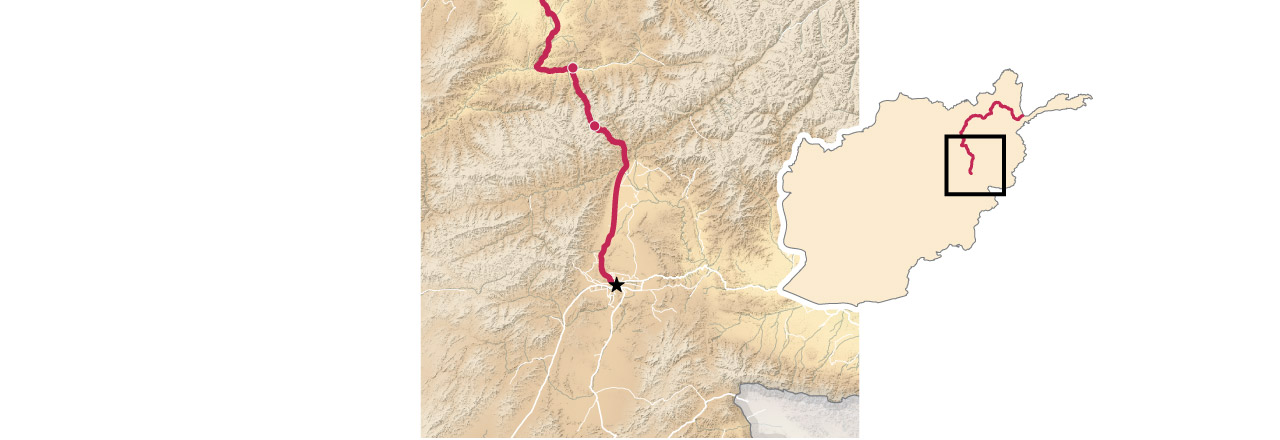

Wary investors

To reach the Wakhan Corridor from Kabul, we first had to follow the main road north, eventually passing through the infamous Salang Tunnel, a claustrophobic, smog-filled 1.7-mile passage built by the Soviet Union at an altitude of over 11,000 feet, where even the most seasoned travelers can experience altitude sickness. The tunnel was a remarkable engineering achievement when it was built in the 1960s, but today, with heavier traffic volumes, travelers often find themselves mired in long jams. The Taliban has announced plans to build a second tunnel, but the cost could be prohibitive.

Upgrading the roadways to Wakhan and then constructing a connecting road to China could require financing like that in the Cold War, international organizations suggest, when the Soviet Union and the United States pumped money into the country because they saw it as strategically important.

Supporters of the Taliban say there has been a noticeable increase in the construction of infrastructure under its rule. But much of that work has been in cities like Kabul, rather than on the eroded network of Afghan highways spanning thousands of miles.

One reason for the continued neglect of highways has been a lack of international funding due to the Taliban’s crackdown on women’s rights, according to foreign donors. Western governments are wary of being seen as supportive of the regime; many international donors have yet to resume funding for major development projects; and Afghanistan’s banking system remains internationally ostracized.

Still, many Afghan men in places like Baghlan — at the north end of the tunnel — are optimistic about the future because the withdrawal of U.S. troops put an end to the country’s long war. Mohammad Wali Baghlani, a 60-year-old businessman in Baghlan, says his region’s golden era is still ahead.

But for women, peace has come at a steep cost. “We’re waiting for a miracle to happen,” said a 23-year-old woman in Baghlan, speaking on the condition of anonymity to avoid drawing scrutiny from the regime.

Security fears

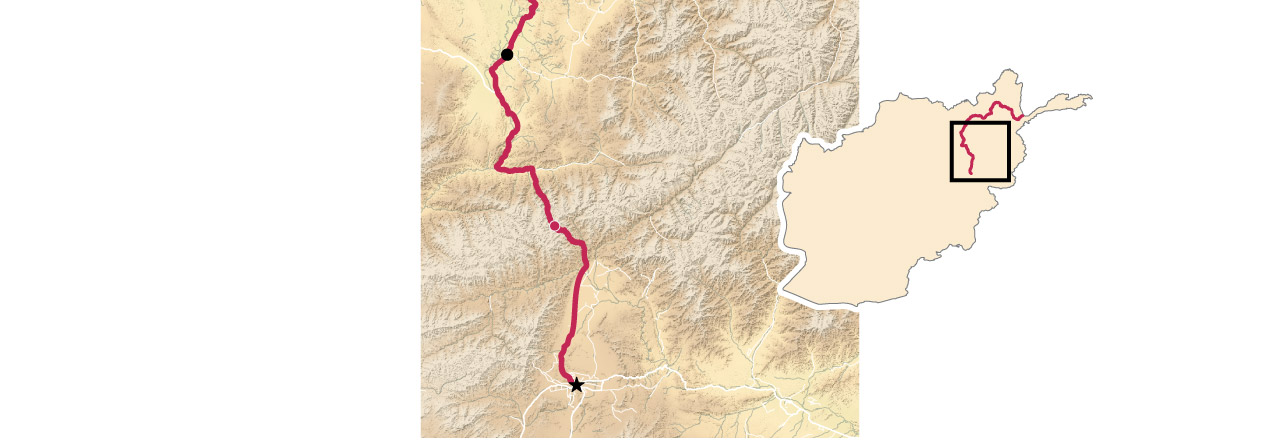

Beyond Baghlan, the road eventually came to a junction and we turned east, arriving before too long at Taleqan. Under the Taliban’s plans for the Wakhan Corridor, this city would become a major transport hub.

These days, convoys carrying Taliban soldiers race along Taleqan’s roads with sirens blaring. Rumors of robberies and militant attacks are ubiquitous. Such security fears could derail the Taliban’s plans for Wakhan, in part because violence could scare off the Chinese engineers and other experts that the Afghan government is counting on. Continuing attacks could also depress commerce.

Islamic State-Khorasan, the local Islamic State affiliate, has asserted responsibility for numerous attacks in various parts of Afghanistan since 2021, including a December 2022 assault on a hotel in Kabul that injured five Chinese citizens. ISIS-K views the Chinese government as a target, railing against what the group has called “China’s daydream of imperialism.” The increasing reach of the militants was illustrated late last year when a bombing claimed by ISIS-K killed an Afghan cabinet minister, Khalil Haqqani.

In neighboring Pakistan, attacks that have killed 20 Chinese nationals since 2021 brought a strong reaction from the Chinese government, which warned that plans for major construction projects could be in jeopardy and demanded that the Pakistani government take action against the militants responsible for the violence.

The Taliban claims it isn’t worried. “Finally, after four decades of war, we have reached full security across the country,” reads a large roadside billboard on the way north.

But the closer one gets to Afghanistan’s northern border, the more hushed conversations become about the security situation and the more guarded the behavior, with residents often avoiding eye contact. Government snipers were positioned above Taleqan’s market square.

At the end of an interview, Zabihullah Ansar, head of the Taliban’s information directorate in the city, advised us to keep a low profile and hide our foreign identities. “The security situation is dire,” he said.

Someone to blame

More than 100 miles farther east, we finally reached the Wakhan Corridor. It is here that the Taliban dreams of a vibrant commercial artery. Today, it is home to little more than sleepy, neglected villages. The main road is patched together from gravel and pavement, and mostly devoid of traffic.

At the town of Ishkashim, at the western entrance to the corridor, a slogan carved into the mountainside by the previous Afghan government still welcomes visitors. It reads, ironically, “Education For Everyone.” The Taliban has banned girls and women from secondary and university education.

“Maybe, if the road was opened and foreigners came from afar, the Taliban would have to give us more freedom,” mused a 25-year-old woman.

But there is a widening gulf between ambition and reality in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. And as this gap becomes more obvious, some Afghans are looking for someone to blame.

Without providing evidence, local officials in the region are spreading word that foreign powers are behind a plot to prevent the Wakhan road from ever being built. Some Taliban officials and supporters claim that neighboring Pakistan, which could lose the most if the highway is built, may be preparing to invade Afghanistan to block the project.

Paranoia seems to be on the rise here. In Wakhan, Mohammad Zakir Ahmadi, a 54-year-old shepherd, said he was stunned to pass 150 Taliban security checkpoints over two weeks while herding about 20 of his yaks through the corridor.

There is little here to suggest a new future for Afghanistan. But the wreckage of Russian tanks rusting in riverbeds and abandoned NATO military bases with faded camouflage tarps offer ample reminders of the past that Afghans dream of leaving behind.

Lyric Lee, Haq Nawaz Khan, Sarah Cahlan, Shaiq Hussain and Fariba Akbari contributed to this report. Graphics by Amaya Verde and Jarrett Ley.

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign