Afghanistan Analysts Network

On 1 January 1965, 27 men[1] (apparently there were no women present) established the Hezb-e Demokratik-e Khalq-e Afghanistan as it was called in Dari, or De Afghanistan de Khalqo Dimukratik Gund in Pashto (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) in English) during a meeting in a modest house in Sher Shah Mena, in the Karte-e Chahar neighbourhood, just south of Kabul University’s sprawling campus.[2]

The PDPA was one of the groups that took advantage of the political opening that followed the adoption of a new constitution in 1963. This constitution had transformed Afghanistan from a semi-absolute into a more constitutional monarchy that included elements of parliamentarianism – although not for the first time.[3] In principle, the new constitution allowed the formation of political parties for the first time in Afghanistan’s history. However, the law on political parties, which was passed by parliament, was never ratified by King Muhammad Zaher Shah. This left the emerging parties, including the PDPA, in legal limbo – and led some of them – not only those on the left but also Islamists – to contemplate violent means of taking power.

When parliamentary elections were held in 1965, none of these parties could field candidates under their own names, although their political affiliations were widely recognised due to their increased public activism.

Most, if not all, of PDPA’s 27 founding members belonged to clandestine leftist study circles, or the so-called mahfels, most of which had sprung up in the early 1960s, with at least one mahfel dating back to 1956. There were 10 to 12 such circles in Kabul, with less than 70 members collectively, according to Tajik author Qozemsha Iskandarov.[4] Some of them counted military officers in their ranks, a fact that would prove to be significant in later coups.

Several of these circles aligned themselves with Marxism-Leninism, choosing the Soviet Union as their ideological guide. Some had more social democratic, non-revolutionary outlooks. There were also Maoist groups inspired by the People’s Republic of China, which were known locally as Sholayi, a nod to their publication Sho’la-ye Jawed (Eternal Flame), but they generally maintained their distance from the other groups.[5]

Among the reported PDPA founding members, only two came from the working class, as noted by Iskandarov – Muhammad Alam Kargar and Mulla [sic] Muhammad Isa Kargar – neither was elected to the party’s Central Committee, which was comprised of seven full and four alternate members – mainly of intellectuals, often school or university teachers. There were also several students present at the PDPA founding congress, according to one of the author’s sources, but the source could not remember whether they were ‘guests’ or party members.[6]

The host of the party’s founding congress, Nur Muhammad Tarakay,[7] was elected as the party’s leader. Born into a poor Pashtun family in 1917 in the Muqur district of Ghazni province, Tarakay was a schoolteacher with a background in social activism, mainly in rural Afghanistan. Babrak Karmal, a former student protest leader and son of a lieutenant general in the Afghan Army with ties to a branch of the monarchy and who was 12 years younger than Tarakay, was seated as his deputy. Both men would later become head of state, the latter directly instated by Soviet troops (more on this later).

From the outset, the party had ambitious goals. It published its first party programme in its short-lived newspaper, Khalq(The People), in 1966. The programme defined its primary political aim as the “establishment of a national democratic government” composed of “the national progressive democratic and patriotic forces, ie the working class, peasants and the national bourgeoisie.”[8] It clearly saw itself as part of, if not leading, this government. In Marxist-Leninist theory, a ’national democratic’ revolution constituted the first ‘stage theory’ of revolutionary change toward socialism. This was underscored by Tarakay when he described the PDPA as “the Party of workers and peasants,” representing “95 per cent” of the Afghan population, in his inaugural speech at the Party’s founding congress.[9]

While the PDPA avoided using Marxist-Leninist terminology in public and did not call itself Marxist or communist, there was little doubt about the party’s driving ideology internally. As Tarakay, in his 1965 speech at the congress, alluded: “Our party is the party of the working class … [it] struggles in conformance with the epoch-making ideology of the workers.” Furthermore, the PDPA defined itself in its 1966 programme as being part of the “struggle between world socialism and world imperialism, which was started by the [1917] Great Socialist October Revolution” in Russia.

At the time, none of the founders could have imagined that, 13 years later, the PDPA would be in power, shaking Afghanistan’s political and social foundations. While the 1978 coup d’état that brought the PDPA to power was not the first successful coup in Afghanistan’s history, it is the one that plunged the country into turmoil, setting into motion a series of events that reshaped Afghanistan’s future and fashioned its relations with the rest of the world for decades to come.

The PDPA’s early years – two factions and two coups

The PDPA did not arrive out of the blue on Afghanistan’s political landscape. The 1963 constitution opened the way for various political groups across the spectrum to engage in public activities, ranging from pro-royalist to leftist movements and from Islamists to ethno-nationalists. The rapid growth of the educated class resulted in profound changes in Afghanistan’s social fabric, which in turn resulted from Amanullah’s reforms in the 1920s. These reforms, which were not adequately embedded due to the stagnating, corrupt state bureaucracy that dominated until 1964 by the extended royal clan, led to the country’s educated youth turning into a fertile recruitment ground for political activism.

Some of these groups, particularly those on the left, saw themselves in the tradition of earlier modernists and reformists. The PDPA later referred to Afghanistan reclaiming its full independence under Amanullah in 1919 as the beginning of the struggle for the country’s “dispossessed and downtrodden” against “despotism and reactionary forces.” The elder statesman among those activists was historian Mir Ghulam Muhammad Ghobar, a former official in Amir Amanullah’s government. Tarakay and Karmal were activists in the Wesh Zalmian/Jawanan-e Bedar (Awakened Youth) movement, which was active during a brief period of guarded political liberalisation during the premiership of Shah Mahmud Khanbetween 1947 and 1952.

The Wesh Zalmian movement had been motivated by the country’s “poverty and backwardness.” These two terms came up again in the 1966 PDPA party programme, where they were attributed to the “feudal system” the party vowed to abolish.[10] Poverty and backwardness were the two major domestic factors underpinning the mobilisation of reformist political groups (see also AAN’s report How It All Began: A short look at the pre-1979 origins of Afghanistan’s conflict).

A few years after the Wesh Zalmiyan movement was suppressed, the reformists who had not been incarcerated began to cautiously regroup. An “initial nucleus” emerged in 1963 from the mahfels, which sought to set up a broad-based United National Front of Afghanistan, Lyakhovsky noted. In addition, Iskandarov writes of a meeting that took place on 17 Sunbula 1342 (8 September 1963) in the house of writer R.M. Herawi,[11] with the participation of Tarakay, Karmal, Mir Akbar Khaibar, Taher Badakhshi, Karim Misaq, Muhammad Seddiq Ruhi, Ali Muhammad Zahma and Ghobar. This meeting, he writes, resulted in the establishment of a provisional committee (komita-ye sarparast) for the Front. At this time, there was also contact with the social democrats led by historian Mir Muhammad Seddiq Farhang and Hadi Mahmudi’s Maoist group, he notes.[12]

Ultimately, the Front fell victim to “the differences between Karmal and Ghubar about political and organisational matters,” according to Iskandarov. Ghobar wanted to continue to act within the framework of the new constitution and the constitutional monarchy, and feared a party that would base itself on openly “communist ideology” (as Karmal seemed to prefer) would soon face “terror” from the government’s side, he wrote. This position seemed to have been shared by the social democrats, who dropped out of discussions, while the Maoists remained.[13]

When the Front failed, a narrower, more revolutionary-minded group, including Tarakay, Karmal, Khaibar, Badakhshi and the Maoists, came together to establish the PDPA, but the latter two soon dropped out – the Maoists left the group during the congress and Badakhshi, who prioritised the ‘national [ethnic] question’, above the PDPA’s class question, as being the main fault line in Afghanistan also left and went on to establish his own organisation, Settam-e Melli ([Against]National Oppression), in 1968.[14]

The PDPA’s unity proved to be fragile, and in 1967, only two years after it came into existence, the party split into two main factions – Khalq (The People) and Parcham (The Banner) – named after the party’s short-lived newspapers.[15] Analysts attribute the split to either ethnic factors, suggesting that Khalq was dominated by Pashtuns, while the Parchamis were mainly Tajiks or Farsi/Dari speakers; or to tactical or personal differences between the leaders of both factions. In reality, it was a combination of all three, with the ‘ethnic’ factor being more of a social one. Notably, many Parcham leaders (such as Karmal and later Najibullah) were Pashtuns, too.[16] But they belonged to a more urban milieu, some even with links to the regime, both the monarchy and later to Daud’s republic (1973-78). The teacher-dominated Khalq, in contrast, was based in a more rural milieu.[17]

Both Parcham and Khalq separately infiltrated the military and built clandestine networks. Initially, Parcham proved to be more successful, with officers linked to it playing key roles in Afghanistan’s first military coup, led by Sardar (Prince) Muhammad Daud, who belonged to the monarchy and served as prime minister from 1953 to 1963. During his decade-long premiership, Daud initiated vast modernisation programmes, but his political ambitions were disrupted by the 1963 constitution, which excluded members of the royal family from holding political positions. By 1973, the monarchy had manoeuvred itself into a legitimacy crisis because of its inadequate response to the drought of 1969–72, the country’s first large-scale environmental crisis. The Daud-led coup succeeded without much resistance from the armed forces or the public.

Daud, however, sidelined his erstwhile Parchami allies in 1975 and 1976,[18] and the PDPA set out to remove him from power through their surviving networks in the military. In 1977, prompted by the Soviet Union and with mediation by the Iraqi and Indian communist parties and leaders of the leftist, mainly Pashtun, National Awami Party (NAP) in Pakistan,[19] Parcham and Khalq formally reunited (although their military networks remained separate).

These military networks played a decisive role when, on 17 April 1978, Mir Akbar Khaibar, Parcham’s main ideologue and a military officer himself, was assassinated.[20] The question of who Khaibar’s assassins were is hotly debated to this day. Some claim it was Daud’s intelligence services, while others point to Amin himself, who, they argue, hit two birds with one stone: getting rid of an influential, popular rival and taking over both factions’ PDPA military apparatus.[21]

The party was able to mobilise large crowds for his funeral procession, which turned into powerful protests. Daud’s regime cracked down, arresting almost the entire PDPA leadership. Only one leader, the leader of Khalq’s military wing, Hafizullah Amin, would initially escape. This gave Amin time, according to the Party’s account, to trigger the 7 Saur 1357 (27 April 1978) coup d’état, with support from a group of young PDPA-aligned military officers, some of them trained in the Soviet Union, who had also been involved in Daud’s 1973 coup.[22]

Although the 1978 military coup was not triggered, or accompanied, by a popular uprising, the PDPA dubbed it the ‘Saur Revolution’, so named after the month in the Persian solar calendar in which it occurred. On 27 April, troops based at Kabul International Airport started an assault on the city, including an air raid on the Presidential palace (Arg), seizing control of state institutions and communication infrastructure. Daoud was executed the next day along with most of his family. Two days after the coup, the ruling Revolutionary Military Council handed power over to Tarakay and the PDPA, who established a civilian government. Tarakay called the coup a shortcut to “the people of Afghanistan’s destiny,” circumventing the ‘national-democratic’ stage and going directly to the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ under the leadership of its party to which the PDPA claimed to be.

This was echoed in the lyrics of the national anthem written by Suleiman Layeq, who had himself had several tenures in the PDPA leadership, even though he had been repeatedly sidelined. Verse 2 of the anthem, which was in use in use from 1978 to 1992, reads:

Our revolutionary homeland

Is now in the hands of the workers.

The inheritance of lions

Now belongs to the peasants.

The age of tyranny has passed,

The turn of the labourers has come.

(Read and listen to the anthem here.)

The military takeover initially succeeded without much resistance from the armed forces and with little bloodshed. In fact, there had been some public outpouring of support, at least in Kabul. (The PDPA, on occasion, had proven capable of mobilising public rallies, for example, at the annual 1 May Labour Day.)

Encouraged by this, the PDPA established a one-party state, imitating the countries of the Soviet bloc, dropping its rhetorical commitment to a ‘broad front of all progressive forces.’ It embarked on a radical reforms programme to abolish feudalism, including land reform, the cancellation of debt, equal rights for women and coeducation. It began to use Marxist terminology more openly and replaced the country’s tricolour flag with the red flag of its party. At Kabul International Airport, a signboard greeted visitors with the slogan: “Welcome to the country of the second model revolution” (only preceded by Lenin’s 1917 October Revolution in Russia), proclaiming the PDPA government nothing less than the model for revolutionary change in the Third World.

All this was deemed as ‘anti-Islamic’ in parts of the still overly religiously conservative population, leading to – apparently – at first spontaneous local uprisings, when revolutionary cadres suppressed resistance against the practical implementation of reform measures with violent means. Cadres, often teachers, were killed by rebels, and schools burned down. It is difficult to gauge who started the violence, but it quickly escalated and the regime carried out mass repressions.

A new outbreak of factionalism fuelled the PDPA leadership’s paranoia. The Khalqis accused the Parchamis of plotting against them in the summer of 1978. By November that year, their most important leaders had either been imprisoned or sent abroad as ambassadors (most of whom quickly abandoned their positions to go into exile). Some were arrested and put in Kabul’s Pul-e Charkhi prison, and some were sentenced to death. The PDPA officially declared five political groups as enemies: Parchamis, the Islamists, the Maoists and Settamis, the Pashtun ethno-nationalists of the Afghan Mellat party and independent intellectuals. Many people who belonged to those categories – or were perceived to do so – were arrested, killed or ‘disappeared’, sometimes with their whole families. Torture and massacres of civilians in rebel areas were widespread. All the former elites – mullahs, landlords, and intellectuals – became targets. Even school children were killed and arrested when they participated in, or even watched, street protests.

Some PDPA cadres seemed to have been inspired by the Khmer Rouge (or Stalin) playbook, trying to physically ‘eliminate’ the ‘oppressor class.’ An elder from Uruzgan province related to the author in 2008 how local PDPA cadres invited local tribal elders to a jirga to discuss matters, arrested and tied them up with ropes, and flew them out by helicopter, never to return (read more about in this AAN report by AAN guest author, Patricia Gossman).

Splits also emerged among the Khalqis, driven by Hafizullah Amin, who had not been among the PDPA founders but had cultivated a close relationship with Tarakay after returning from studies in the US. After the April coup, he became deputy party leader and deputy prime minister. In mid-September 1979, Amin sidelined Tarakay and took over as the head of the party and the state. He had Tarakay assassinated three weeks later, on 8 October. Whether this was about political differences or pure ambition for power is unclear. Initially, Amin accused Tarakay of being responsible for the mass arrests and murders, but the repression only increased under Amin’s rule and the resistance spread and coalesced into various factions of the mujahedin. The Islamists were able to secure more and more funding and arms from the West, Arab countries, Pakistan, Iran and China, while the secular factions were sidelined. Whole army units and garrisons mutinied and joined the rebels.

In the context of the ongoing Cold War, which had reached a peak in the 1970s with the US defeat in Vietnam, the success or at least progress of liberation movements and leftist coups in Africa, the Middle East and Central America (the Soviet Union even tried to embrace the ‘anti-imperialist’ Islamic revolution in Iran), Afghanistan’s internal conflicts, which were basically about modernisation, were internationalised. For more than four decades now, Afghans have endured repeated cycles of internal conflict and war.

The Soviet invasion

Over the Christmas period in 1979, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan, apparently to rescue the troubled PDPA government. It was ‘rescued’ (for another 13 years) and was significantly altered in the process. The Soviets overthrew and killed Amin on 27 December. They installed the Parcham faction in his place as part of an alliance with some former Khalqi officers that Amin had sidelined, with Karmal as head of party and state.

The Soviet Union, although initially wary of the notoriously divided PDPA, had nevertheless become its key backer. It usually only recognised one communist party per country, and bilateral party relations remained low-key. Several analysts have suggested that while Moscow was ready to live with the Daud regime despite some bilateral hiccups, the PDPA presented the Soviets with a fait accompli when it took power in the 1978 coup. Moscow did not want to see its allies fail. Additionally, then-party leader Leonid Brezhnev had apparently developed personal sympathies for Tarakay. When Amin had him killed, the Soviets’ patience with Amin, who had also proven himself a turbulent ally – with rumours that he was about to make a deal with the militant Islamist opposition and Pakistan, his possible CIA links and his outreach to the US embassy in Kabul – ran out.

Source: Janet Geissmann via Pintrest

The Soviet leadership believed Parcham to be closer to their own interests, less radical and possibly – with Moscow’s support – capable of ensuring that instability could be contained at the USSR’s southern border. As it turned out, Soviet troops did not leave after a short time, as had apparently been the initial plan, rather they remained and were increasingly actively drawn into counter-insurgency operations, contributing to the further escalation of fighting and further internationalisation of Afghanistan’s internal woes, with Western, Arab, Pakistani, Iranian and Chinese support for the insurgents, and drawing in thousands of foreign jihadists who established a worldwide movement active to this day.

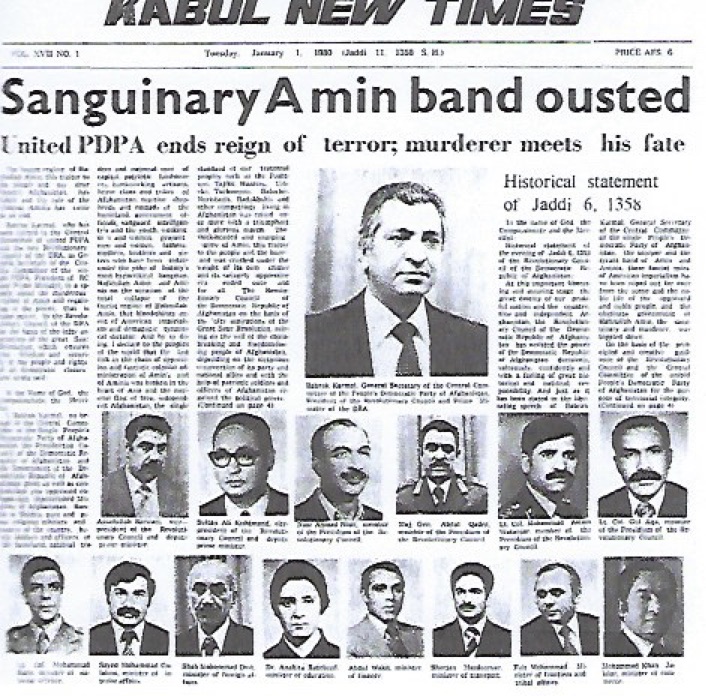

Initially, in the last days of 1979 and the first ones of 1980, there were jubilant scenes – reminiscent of what we have recently been able to observe in Syria – when the new government opened prison doors and thousands of incarcerated enemies, real or imagined, of the previously ruling Khalq faction were set free (the government-controlled media of the time reported that 15,000 people had been released).[23]

After the Soviet invasion, the Parchamis reciprocated internal purges of the party that the Khalqis had carried out. They even executed Tarakay and Amin’s alleged killers, whom they claimed had been sentenced to death by a military court. (In fact, Amin was shot dead by Soviet special forces.)[24] In contrast, most Parchami leaders had survived jail under the Khalqis. This perpetuated the split between the two factions.

Soviet support and troops, initially moving in for only a short mission, were unable to quell the resistance and became increasingly involved in their own version of ‘mission creep’, taking over more and more fighting and governance functions. The intelligence state, with sham trials and executions, became more systemic. Both Soviet and Afghan government forces carried out indiscriminate bombings in the countryside, resulting in mass casualties and forced displacement of five million Afghans to Iran and Pakistan. Soviet troops stayed for ten years. The mujahedin did not shy away from using the most egregious forms of violence against civilians who sided with the regime.

Gorbachev, Yeltsin and Najibullah: withdrawal

By the mid-1980s, the Soviet leadership – particularly under Mikhail Gorbachev (1985-91) – realised they were fighting an unwinnable war. The country’s involvement in Afghanistan had impacted the ailing Soviet economy and stood in the way of disarmament and its détente with the West. Then-Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, called the Soviet war in Afghanistan a “festering wound.”

Gorbachev replaced Karmal with Najibullah as Afghanistan’s head of state and party, and in 1985 and 1986, compelled him to introduce his own versions of perestroika and glasnost.[25] The overarching aim was to put the Kabul regime on its own feet economically and militarily, withdraw Soviet troops and cut costs at home. Attempts were made to end the war through negotiations with the mujahedin under the title of siasat-e ashti-ye melli (policy of national reconciliation). Among other measures, in 1990, Najibullah renamed the PDPA Hezb-e Watan (Homeland Party), dropped most of the party’s leftist symbols and politics and established a half-baked multi-party system and (still heavily manipulated) elections (see AAN’s backgrounder). According to Najibullah, it had been “a historic mistake” to come under “a specific ideology.” In its new programme, Hezb-e Watan committed itself to a “democracy based on a multi-party system.” However, almost all the PDPA leadership was transferred to the new party.

It proved to be too little too late. Aside from splinter groups that had emerged, the mujahedin spurned the talks, preferring not to talk about sharing power with the PDPA but instead opting for an all-out victory.

Najibullah‘s government held out against the mujahedin for another three years after the last Soviet troops withdrew in February 1989. Its downfall came only in 1992 when Yeltsin cut the Soviet Union’s funding and various pro-PDPA militia leaders switched sides to the emerging winners. A Parcham sub-faction toppled Najibullah (himself a Parchami) and handed power over to the mujahedin, who would enter Kabul and take the reins without a fight.

The new mujahedin government dissolved the Watan Party, confiscated its property and established a court to bring “traitors and invaders” to justice. However, it also declared an amnesty for ordinary PDPA members (see The Christian Science Monitor ). This did not prevent all the revenge killings (see Amnesty International’s ‘Afghanistan: Reports of torture, ill-treatment and extrajudicial execution of prisoners, late April – early May 1992’).

These were not the last words on the PDPA, though. At various times thereafter, there were attempts to revive it by reuniting the diverse parties and factions founded by former members of the disintegrated PDPA/Watan Party in the country or in exile. None of them succeeded, leading to further splits between former Parchamis and Khalqis, between Tarakists and Aminists (who say he was a real patriot because he opposed the Soviets – after all, he was killed by them), between Karmalists and Najibists, the former saying that ‘national reconciliation’ was a betrayal of the ‘revolution’ and the latter insisting that it was the only way to peace. At times, there were at least 25 registered parties – and even more unregistered ones – that went back to PDPA’s origins. The name PDPA itself was never used again, although there was an attempt in the early 2000s to establish a party with a name close to the original one, which was prevented by the Ministry of Justice’s party registration office, saying the ban dating back to the mujahedin times was still valid.

To this day, even though all parties are banned in Afghanistan itself, various groups with roots in or affinity with the PDPA remain active among the diaspora.[26]

The ‘Sovietisation’ of Afghanistan

There is an ongoing, albeit diminishing, debate surrounding the alleged ‘Sovietisation’ of Afghanistan and who the driving force behind it was: the Soviets or the PDPA?

A particular point of view here is the reluctance on the part of the Soviets to engage with the divided PDPA prior to 1978. Sources indicate there were varying approaches among the Soviet intelligence services (KGB, GPU), the party, and various ministries. It is also possible that certain officials acted on their initiative in the Afghan hinterlands that did not seem to be a political priority in Moscow – or that the CPSU or certain Soviet intelligence services used them tactically to maintain a degree of ‘plausible deniability.’

During the Cold War, however, many Western authors broadly agreed that the USSR – after its military invasion in late 1979 – intended to ‘sovietise’ the Afghan regime and incorporate it into its worldwide system. One of them, Anthony Arnold, even considered that “by the close of 1979, the PDPA no longer ruled Afghanistan; the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] did.”[27] Indeed, the Soviet party leadership had established a powerful Afghan task force on the level of its Polit Bureau in October 1979, and had dramatically increased its number of military and civilian advisors.

Artemy Kalinovsky, Professor of Russian, Soviet, and Post-Soviet Studies and author of a number of books on Soviet engagement in Afghanistan, argued that Soviet advisors tried to caution Afghan party leaders against their revolutionary fervour. This Soviet exercise in nation-building “had little to do with the desire to spread communism [but was rather] … motivated by a desire to stop the deteriorating situation” in Afghanistan and prevent it from aligning itself with the US, he said. It was, he noted, “composed of ‘off the shelf’ components, not a master plan … founded on [Soviet/Marxist] ideas but improvised in practice.”[28]

Clearly, there were ideologues among the Soviets who dreamt of a worldwide victory of socialism. In their view, Afghanistan would be part of this. Others were sceptical about Afghanistan marching toward socialism under the PDPA. They often quoted Lenin, who had warned against exporting it to a southern neighbour. Initially, therefore, there was little Soviet enthusiasm about the PDPA, but after the party’s takeover, the Soviets thought they had to live with the situation. The mood swung when Amin came to power, and the leadership in Moscow made the fateful decision to intervene directly. When mission creep, caused by the lack of Afghan capacity or by corruption, had them take on more and more responsibility, all they knew was how to look at Afghanistan through a lens of ‘Soviet’ Central Asia. Methods employed there, such as coeducation or the unveiling of women, were copied in Afghanistan. (Although the PDPA, taking a page from the Soviet book, had started this before the invasion.)

At the same time, the PDPA had built its own party based on the Soviet model, a hierarchically led mass membership party that, when in power, took over and even largely replaced the structures of the state, including the armed forces. (By 1983, 60 per cent or more of all PDPA members served in the army and police.) When in trouble with the resistance, the PDPA realised it was fully dependent on Soviet support, financially and militarily – and was, therefore, interested in presenting itself as a good student of Marxism-Leninism.[29] When the Soviets stepped in, a ‘Soviet’ framework was already in place and they were left with little choice but to follow its logic.

Many in the PDPA, at the same time, tacitly derided the Soviets, who took over more of the decision-making than they probably expected. They tried to manipulate them for opportunistic reasons, power or pure survival – or even undermined them actively, secretly cooperating with the mujahedin.

Despite the omnipresence of Soviet advisors – many of them ill-prepared to work in Afghanistan or to understand Afghans,[30] Afghan leaders were able to maintain space for independent manoeuvring and decision-making. The room for this was provided by the notoriously segmented Afghan structures, factionalism and political power games as well as the institutional and personal rivalries among the different groups of Soviet advisors. In effect, decision-making on the ground and, subsequently, political responsibility were shared between Afghans and Soviets. There was no Soviet domination.

What emerged was a classic case of a dialectical relationship in the Marxist sense, in which two mutually dependent actors impacted each other and created (often undesired) effects. In the end, it became clear, however, that Afghans were more dependent on the Soviets than the Soviets were on the Afghans. History later repeated itself with other actors.

The Soviet attempt to turn Afghanistan into another ‘Central Asian Republic’ lasted until 1986, when “the failure of their project drove them to prepare the ground for withdrawal and to push for the ‘policy of national reconciliation,’” as French author Gilles Dorronsoro wrote.[31]

In summary, the PDPA can be described as a wannabe communist party that from its establishment – not very openly, but clearly enough – declared its aim of being part of the Soviet-led ‘socialist world system.’ Before 1978, however, it was ideologically kept at arm’s length by the USSR and its allies. After the 1978 coup, however, once it became a ruling party, its overtures forced the USSR, bound to Brezhnev’s doctrine that revolutionary change must be ‘irreversible’, to support its regime.

The 1979 intervention had two contrary effects on the relationship between the PDPA and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU): the PDPA followed a strategy of further expanding its copycat Soviet model to present itself as an indispensable ally while the Soviets, realising the social and political situation in Afghanistan was not ripe for socialist development, cautioned the PDPA in its ‘revolutionary’ development and, under Gorbachev, concentrated on withdrawal, ready to sacrifice their erstwhile ally.

Feminism and the PDPA

Despite the party’s contribution to plunging Afghanistan into four decades of war and destruction, as well as its responsibility for undoubted systematic human rights violations and war crimes, many of its members and sympathisers were driven by a genuine yearning for reform and modernisation. Sulaiman Layeq – who came from a leading religious family – said in a BBC Persian interview that it was the poverty he experienced in the tribal society of his childhood and the injustices during his school years that made him join the party. Soraya Parlika, a staunch feminist and communist PDPA member, hailed from an upper-class family. She was for many years the head of the PDPA-affiliated Democratic Women’s Organisation of Afghanistan (DWOA), which she said she established together with five other women as an independent organisation in June 1965, only six months after the founding of the PDPA. Parlika told the author: “My mother, mainly, often said that not all Afghans lived as comfortably as we did. That motivated me to engage politically.” She did so, despite her prominence after the fall of the PDPA, and stayed in Afghanistan, organising clandestine schools under the Taleban and continuing to do so after 2001.

Women in particular had considerably more rights, at least in urban areas and when not opposing the regime. The DWOA, before the PDPA took over, supported female victims of domestic violence, tried to mediate with families and helped women take their grievances to court. It organised literacy courses and tried to encourage women to seek employment and send their children to school. It mobilised women to take part in the 1965 parliamentary election, which Parlika was actively involved in, going to the countryside to teach women how to read and write. In 1968, she participated in demonstrations against a draft law proposed by conservative Islamic members to ban girls and women from travelling abroad to receive an education without a mahram. After a month of protests, including an occupation of the parliament, the bill was dropped.

During its period in power, the PDPA government – thanks in large part to the DWOA and Parlika’s work – extended maternity leave to 90 days, with an additional 180 days of unpaid leave. Women were legally allowed to retire at the age of 55. When Parlika passed away in December 2020, the Ministry of Justice’s website still showed the 1979 PDPA maternity leave law as still being in force. Parlika’s advocacy also resulted in the establishment of nursery schools and kindergartens in the workplace (see AAN’s obituary for Parlika).

These were big achievements, even though for women in the countryside and in mujahedin-controlled areas, these rights remained theoretical – resembling the situation post-2001. Nevertheless, these accomplishments left an indelible mark on the lives of Afghan women and continue to be valued to this day.

Conclusion

The PDPA, along with its predecessor Hezb-e Watan, existed for less than three decades. Few other indigenous political forces, however, have influenced Afghanistan’s modern history as significantly. One notable exception is King Amanullah, whose reforms, although officially halted in 1929, had lasting and sustainable impacts. The other influential forces—the mujahedin and the Taleban—emerged in part as a reaction to the PDPA’s modernist reform programme, which was inspired by the Soviet Union. Their ideological roots can also be traced back to Amanullah’s opponents (see, for example, AAN’s report about the Khost Rebellion of 1924).

The Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan not only dealt a final blow to any support the PDPA once had among segments of Afghan society but also led to its demise as a recognisable political force. The debate surrounding the events that unfolded after the PDPA was established 60 years ago continues not only among Afghans but also in academia as people continue to explore the underlying causes of these events and the role the Soviets had in influencing them.

Whether the PDPA’s founding in 1965 and its takeover of power in 1978 were initiated by the Soviet Union with full-fledged support from the CPSU is questionable, at least from this author’s perspective. What is certain is that the PDPA soon ran into resistance, and violence escalated on all sides. Even for those who have been engaged with Afghanistan and its people, it is still difficult to explain where the staggering level of violence – mass killings, institutionalised torture and widespread repression – that emerged on all sides in the conflict originated from.

Many of those involved in the PDPA in key positions, including Layeq and Parlika, never publicly spoke out against the atrocities committed by their party while it was in power. Some former PDPA officials even insisted, officially, that after their time in power, things took an even nastier turn under the mujahedin and the Taleban, particularly when it came to women’s rights. Many regularly quote late-President Najibullah’s warnings against the ascent of Islamists. One former PDPA Central Committee member told the author: “I am proud of my past because I was always in the service of the people.”

Indeed, there is a growing number of non-PDPA Afghans who praise, in hindsight, some aspects of the PDPA government. A sympathiser of the late Ahmad Shah Massud once told the author: “There were only two real leaders in Afghanistan’s history: Sardar Daud and Najib,” alluding to their perceived ability to ‘effect change’. A member of the leftist armed opposition to the PDPA regime told the author that he later ‘regretted’ having taken up arms against it, witnessing the reactionary politics that followed after its overthrow.

Sixty years on, the book on the PDPA and its legacy is still being written. As it currently stands, it is important to reflect on the momentous events that have brought us to this day in Afghanistan’s history, to acknowledge the atrocities that were perpetrated in the name of the Afghan people and the immense suffering they have endured and continue to endure. It is, however, important to take stock of the country’s achievements over the past six decades in the face of enormous challenges, and to consider the Afghan people’s quest for a better future. The PDPA may be gone for good but current developments in Afghanistan indicate that the struggle between the forces of modernism and those who oppose it is far from over.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour

References

| ↑1 | Most sources name only those seven who were elected full members of the party’s Central Committee: Nur Muhammad Tarakay, Babrak Karmal, Tahir Badakhshi, Ghulam Dastagir Panjshiri, Shahrullah Shahpar, Sultan Ali Keshtmand and Dr Saleh Muhammad Zeray as well as the four alternate members — Dr Shah Wali, Karim Misaq, Dr Abdul Zaher Ufoq and Abdul Wahab Safi. A full list of all 27 founding members is given in Sayed Mohammad Baqer Mesbahzadeh’s book Aghaz wa Farjam-e Jombeshha-ye Siasi dar Afghanistan (The Beginning and End of Political Movements in Afghanistan, Kabul 1384-2005). In addition to the eleven already mentioned, they include: Nur Ahmad Nur, Dr Muhammad Zahir Dzadran, [Muhammad] Akram [or Alam] Kargar, Suleiman Layeq, Sayed Abdul Hakim Shar’i Jawzjani, Adam Khan Dzadzai, Mullah Muhammad Isa Kargar, Engineer Khaliar, Wakil Abdullah Dzadzai, Abdul Qayum Qayum, Atta Mohammad Sherzai, Ghulam Mohiuddin Zarmalwal, Hadi Karim, Abdul Hakim Hilal, Mohammad Hassan Baraq Shafe’i and Sayed Nurullah Kalali. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | According to Soviet/Russian writer and former general, Alexander Antonovich Lyakhovsky, the PDPA founding congress took place “with the direct assistance of the [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] CPSU”, see Alexander Lyakhovsky, Tragediya I Doblest Afgana (Afghans’ Tragedy and Valor), Moscow 1995. Many others also have emphasised a Soviet role in this event. It is possible that some people in the Soviet embassy in Kabul were aware of, or even actively supported, attempts to first establish the United Front and later the PDPA. Tarakay, according to Lyachovsky, officially visited Moscow for the first time in December 1965, meeting only mid-ranking officials in the CPSU Central Committee. However, according to the late-Soviet/Russian Afghanistan specialist, Vladimir Plastun, who was an advisor to Najibullah in the late 1980s, Tarakay had in fact reached out earlier, when visiting Moscow as early as in 1962, in his capacity as a writer (which he was). According to Plastun, he also met a Central Committee official. After his visit, an interview with him appeared in a Ukrainian literary magazine, which Plastun was later unable to locate (information from conversations with the author). |

| ↑3 | There was also a brief period of political activity between 1947 and 1952, which saw the emergence of opposition groups, a proliferation of media, and even somewhat pluralistic elections before Afghanistan reverted to a more autocratic form of government (for more details, see this AAN report). |

| ↑4 | In his book Polititschekie Partii i Dwizhenie Afganistana wo wtoroi polowine XX veka (Political Parties and Movements of Afghanistan in the Second Half of the 20th Century), Dushanbe, 2004, which this author was able to consult in Tajikistan. |

| ↑5 | See also this declassified US Department of State Air Gram about “The Afghan Left” available in the George Washington University archives. |

| ↑6 | Neither did he remember whether later party chief Najibullah was among them. He was then 17 years old and had just started studying at Kabul University in 1964. |

| ↑7 | This is the correct Pashto transliteration. In most non-Afghan literature, his name is spelled Taraki. |

| ↑8 | Khalq’s 1966 party programme, from a German translation in: Karl-Heinrich Rudersdorf, Afghanistan – eine Sowjetrepublik?, Reinbek 1980, pp 142-149. |

| ↑9 | Quoted from a German translation in: Wolfram Brönner, ‘Afghanistan: Revolution und Konterrevolution’, Frankfurt 1980, pp 165-172. |

| ↑10 | Interestingly, in 1971, Jonathan Neale observed a PDPA-inspired student protest in Lashkargah under the slogan ‘death to the khans!’, see the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism. |

| ↑11 | Iskandarov did not provide Herawi’s first name. |

| ↑12 | According to this author’s information, Ghobar continued to participate in preparations for the PDPA establishment but dropped out later, some say for ideological reasons – he did not want a Soviet-style party. Others cite the fact that he was staying in Germany in 1965 when the PDPA was founded. Plastun told this author that some ‘Maoists’ also attended the congress but withdrew before the PDPA was founded. |

| ↑13 | It was not clear whether Ghobar’s and Farhang’s circles were separate or one; both had cooperated with reformist Watan newspaper and its attempt (which led to its ban) to establish a ‘Watan Party’ during the Wesh Zalmian period. In 1990, the Farhang family protested Najibullah’s choice of Hezb-e Watan for the rebranded PDPA. |

| ↑14 | This was the group’s main political slogan, not its official name, but the phrase took hold as its public moniker. |

| ↑15 | Khalq was the PDPA’s original newspaper, but it was banned after only six issues were published between April and May 1966 as it appeared too closely associated with a political party that had not yet been legalised. Parcham was published between March 1968 and July 1969 (or even 1970, according to some sources). |

| ↑16 | Karmal’s ethnicity, as a Pashtun, is a matter of debate, with some sources speculating that his family were Dari-speaking Kabulis who had originally emigrated to Afghanistan from Kashmir, which was once an Afghan possession (see, for example, Hassan Kakar’s book ‘The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982’, on the University of California E-book collection website). Karmal himself was never keen to dwell on his own ethnic background. |

| ↑17 | Karmal and Khaibar were personally acquainted with Sardar Daud. In Karmal’s case, this went back to the period of the Wesh Zalmiyan. An association that Daud, for a while, attempted to coopt into his own political vehicle against other factions/branches within the monarchy. Karmal’s father was still a general in Daud’s republic. His unofficial partner (he was married to Mahbuba Karmal) and later education minister, Anahita Ratebzad, even had roots in Amanullah’s family. This probably made them more reluctant to plan to overthrow him. More on the Khalq-Parcham tactical differences and related issues in this interesting 2023 International Research Centre DDR (IF DDR) interview with Matin Baraki, as an early PDPA activist and now a professor in Germany. |

| ↑18 | Two cabinet ministers from the Khalq faction, Zeray and Panjshiri, lost their positions. Daud’s decision to weaken the Parchami faction may have been influenced by his desire to form a closer alliance with the Shah of Iran and the United States. Additionally, this decision could have been motivated by increasing suspicions regarding the activities of radical militant groups, particularly due to the growing infiltration of army ranks by PDPA (mainly Khalqi) cells. This situation was further complicated after several Islamist organizations attempted an uprising in the summer of 1975, which ultimately failed. |

| ↑19 | The National Awami Party, or NAP (National People’s Party), not to be confused with the Awami National Party (ANP), was a leftwing political party in Pakistan founded in Dakha (present-day Bangladesh) in 1957. |

| ↑20 | According to Lyachovsky, a coup was planned for August 1978. Layeq claimed in an interview with ToloNews on 24 April 2018 that a coup had never been discussed or planned within the party, and that this was a personal decision by Amin. Layeq, however, was a Parchami and the faction seemed to have preferred peaceful means, while – again, according to Lyachovsky – the Khalqis generally favoured a coup and went ahead without Parcham. |

| ↑21 | Another source told the author that, in a third version, he had later heard Hezb-e Islami claim the killing. Names were even named. Chris Sands also references this in Night Letters, Hurst & Co 2019, p 444, citing a speech given by Hezb-e Islami’s leader, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, to commemorate the eighteenth anniversary of the Muslim Youth’s establishment on April 2, 1987 (available on YouTube). |

| ↑22 | Russian author, Nikita Andreevich Mendkovich, of the Center for the Study of Contemporary Afghanistan (CISA), quotes a Soviet advisor who worked at the Afghan defence ministry in 1978 in a 2010 article: “PDPA functionaries later admitted that they had deliberately concealed information about the planned coup from their Soviet allies, citing the fact that ‘Moscow could have dissuaded them from this action due to the absence of a revolutionary situation in the country.’” He also provides details on how the military officers who implemented the coup had made their decision during a meeting at Kabul Zoo. |

| ↑23 | See the Kabul New Times. (Kabul, Afghanistan), 1980-01-03 from the University of Arizona Library Digital Collections. |

| ↑24 | Several other Khalqi leaders received long-term prison sentences and were only released by President Najibullah in the second half of the 1980s. Some of them were reinstated to government posts or appointed to roles in the newly established National Fatherland Front – an attempt to broaden the regime’s basis and to appeal to the Khalq membership, which still made up the majority of PDPA members in both the army and the police. |

| ↑25 | Despite often being named ‘Muhammad Najibullah’ or ‘Najibullah Ahmadzai’ – the latter version signifying his tribal affiliation – he himself used ‘Najib’ or ‘Najibullah’, or ‘Dr Najib’ or ‘Dr Najibullah’. The author was present in Kabul during part of his rule in 1988-89, and this fact was also confirmed to him by Najibullah’s own family. The story of the change from Karmal to Najibullah was told to the author by the late Suleiman Layeq, a prominent PDPA activist (and, in fact, Hezb-e Watan’s last leader – see AAN’s obituary for Layeq). |

| ↑26 | Amin’s supporters, for example, still gather in the diaspora and maintain the ‘Hafizullah Amin Ideological and Cultural Foundation, as The Diplomat reported in 2019, referencing a video of an event to commemorate Amin, which is no longer available online. |

| ↑27 | Anthony Arnold, ‘Afghanistan’s Two-Party Communism: Parcham and Khal, California: Stanford University, 1983 p 99. |

| ↑28 | Artemy Kalinovsky, ‘The Blind Leading the Blind: Soviet Advisors, Counter-Insurgency and Nation-Building in Afghanistan, Washington, D.C: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2010, Working Paper No. 60, January 2010. |

| ↑29 | In a 1985 speech on the occasion of the PDPA’s 20th anniversary, Karmal went as far as calling the PDPA “the new [Leninist] typus party of the proletariat and all working people of the country” the aim of which was to build “the Afghan society on the basis of socialism.” |

| ↑30 | Kalinovsky, ‘The Blind Leading the Blind’. |

| ↑31 | Gilles Dorronsoro, ‘Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present’, New York: Columbia University Press in association with the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales, Paris, 2005, p 173. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign