News of the pay cap emerged in the last days of May 2024 after the acting Director of the Prime Minister’s Office of Administrative Affairs (OAA), Sheikh Nur ul-Haq Anwar, issued a circular instructing all government departments to set the salaries of all female staff at 5,000 afghanis. The circular had been prompted by an order signed by the Islamic Emirate’s Supreme Leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, which said:[1]

The salaries of all female workers who were employed by the previous government and are currently receiving a salary from the Islamic Emirate should be set at 5,000 afghanis in all budgetary and non-budgetary units,[2] regardless of their previous wages (their salaries should all be the same).

This sentence appears to have been the order in its entirety. It alone was quoted by many media outlets, on social media and in official letters, which were widely distributed (see, for example, BBC Pashto on 6 June and a letter from the Ministry of Economy below).

The news sparked confusion, concern, indeed fear, among Afghan women working in the public sector, which in Afghanistan is referred to as the civil service (see, for example, this report on teachers from ToloNews).[3] Women employed in the health sector in Herat and Kabul held protests, calling on the government not to reduce what they said were their already meagre wages (see, for example, Amu TV here). There was also condemnation from international human rights bodies; the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner, Volker Türk, called on the IEA to rescind the measure, saying “[t]his latest discriminatory and profoundly arbitrary decision further deepens the erosion of human rights in Afghanistan,” (the full statement, issued on 13 June 2024, can be read here).

The vagueness and lack of specificity in the Amir’s one-sentence order sparked questions by employees, the media, social media users and apparently even some state institutions, which urgently sought clarification. For example, the Ministry of Education’s internal correspondence, which was widely shared on social media (see the picture below), asked “whether the decree of His Excellency, the Supreme Leader, applies to all female employees or only those who are not reporting for duty.” The letter also explained that it would take time for the ministry to amend its automated salary payment system to accommodate the change. In response, the acting Minister of Education ordered that “the salaries of all female employees should be suspended until further notice,” presumably until the Amir’s office provided further guidance (see this post on X from 30 June and an English translation below).

The confusion was only cleared up a month later, and then just partially, when on 7 July, ToloNews tweeted some “breaking news”:

[T]he Ministry of Finance confirms to Tolonews that female employees who come to work every day are currently receiving their salaries just like male employees.

The spokesperson of the Ministry of Finance adds that the monthly salaries of female employees who do not show up for their duties have been set at five thousand afghanis.

The following day, Pajhwok quoted the spokesperson of the Ministry of Finance, Ahmad Wali Haqmal: “Only those women who have been compelled to stay at home will be paid 5,000 afghanis … all [other] female government employees, including teachers and doctors, who report to their duties, will receive their salaries as before.”

However, as of this writing, no official written statement or new order clarifying the particulars of the Amir’s instructions has been issued.

The situation is still confused, because it is not clear how the order will be implemented. As the interviews below show, a month after the order, most female employees still did not know how much they would be paid.

What women say

To understand how the order is affecting female civil servants and their families, we interviewed 18 women. Our sample was based on accessibility, that is, we interviewed women in places where we had contacts and/or our network had access. Our interviewees included women who were currently working, those who had been told to stay at home, but were still receiving a salary, and two women who have lost their jobs since the Emirate takeover. We ensured geographic diversity by talking to women in the provinces – Daikundi, Kandahar, Zabul, Ghazni, Balkh, Bamiyan, Panjshir, Sar-e Pul, Farah and Paktia— both in rural and urban areas – and in the capital. The interviewees included a mix of professions – midwife, teacher, prosecutor, administrator, health professional, school principal, etc. The interviews were conducted between 2 and 11 July 2024 and comprised the following questions:

- How many people are contributing financially to your household?

- How much was your salary under the Republic?

- How much is your salary under the Emirate?

- Are you working from the office? Are you being paid, but not going to work?

- When did you last receive your salary?

- Was it 5,000 afghanis or was it the same amount you had been receiving under the Emirate?

- Do you normally get a salary top-up in addition to your base salary (for length of service, rank, qualifications, etc)?

- Have you been officially informed that your salary will be reduced?

- If there was a reduction in your salary, how will it affect the economy of your household and your life?

The table below highlights answers to some of these questions. We have intentionally omitted the occupation and location of interviewees from the table below to protect their privacy. Quotes later in this report do indicate the interviewee’s profession and province while providing no other identifying information.

| Going to work | Only breadwinner | Family size | Salary IRA (afghani)* | Salary IEA (afghani)* | Last salary received | Officially informed | |

| 1 | Yes | Yes | 8 | 13,000 | 13,000 | March-April (Hamal) | No |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | 5 | 15,000 | 12,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 3 | Yes | No | 14 | 14,000 | 6,500 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | 5 | 8,000 | 8,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 5 | Yes | No | 7 | 12,000 | 15,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 6 | Yes | No | 15 | 14,600 | 14,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 11,000 | 9,000 | May-June (Jawza) | Yes |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | 6 | N/A | 8,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | 5 | 26,000 | 19,000 | April-May (Saur) | No |

| 10 | Yes | No | 7 | 18,000 | 13,000 | May-June (Jawza) | Yes |

| 11 | Yes | No | 12 | 35,000 | 14,000 | April-May (Saur) | No |

| 12 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 13,000 | 13,000 | April-May 2022 (Saur) | N/A |

| 13 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 11,700 | 11,700 | Dec ‘23-Jan ‘24 (Jaddi) | N/A |

| 14 | No | No | 6 | 11,000 | 10,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 15 | No | Yes | 6 | 9,000 | 9,000 | May-June (Jawza) | No |

| 16 | No | No | 6 | 23,000 | 11,000 | April-May (Saur) | No |

| 17 | No | No | 7 | 10,000 | 8,500 | Feb-March (Hut) | Yes |

| 18 | No | No | 6 | 9,300 | 8,000 | Feb–March (Hut) | No |

As can be seen, 16 of our 18 interviewees were still on the public payroll. Of the remaining two, one had been fired in May 2022 and the other said she had not heard from her employer since January 2024. However, of the 16 employed women, only 11 were going to work; five had been sent home after the IEA came to power but continued going to the office to sign their attendance sheets as instructed by the Emirate. Of the 11 that were going to work, one had been hired after August 2021 and another who was told to stay home in August 2021, had, in the meantime, been called back into the office because of an increased workload.

The average number of members in a family in our sample was 7.2. Half of the interviewees – nine – were the sole breadwinners for their families.

Most of the women in our sample had already seen cuts in take-home pay in line with the Ministry of Finance’s December 2021 salary reductions, which applied to all workers, men and women. The cuts varied according to grade, but the average was a 9.8 per cent cut.[4]

Three women said they were still receiving the same salaries as under the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (IRA). Three others had seen their salaries significantly reduced after August 2021 – one after being demoted from grade 2 to grade 3.

One interviewee said the Emirate had increased her salary, and later her pay was effectively increased again by an additional 1,000 afghani (USD 14) a month after the Emirate stopped deducting pension contributions in April 2024.[5]

None of our interviewees had received the reduced salary of 5,000 Afghani at the time of the interview, nor had they received their salary for the month of Saratan (22 June – 21 July). 10 out of the 16 had received their Jawza (22 May – 21 June) wages. Three had last been paid in Saur (22 April – 21 May), one in Hamal (21 March – 21 April) and two not since the final month of the last financial year, in Hut (22 February – 20 March). Such delays in the payment of salaries are not unusual.

How did the women find out about the cut?

Only three interviewees said their superiors had officially told them that their salaries would be reduced. A teacher in Farah province said they had been informed about the cut at an official meeting at the Department of Education and told to prepare themselves. She said the payment of salaries for the month of Saratan (21 June – 20 July) had been deliberately delayed because of the new order.

All other interviewees had heard about the planned reduction from their co-workers, group chats, the news or social media. Every interviewee described how anxious and fearful it had made them. For example, one woman working for the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in Sar-e Pul had heard about the news on a group chat:

An official letter [maktub] saying that the salaries of women who aren’t working will decrease to 5,000 afghanis was posted in a [WhatsApp] group. I don’t know much about it because I haven’t been officially informed, but the letter was posted in a WhatsApp group that was created to deal with the central government’s budgetary issues. There are employees from different government offices in the group.

An employee of the National Statistic and Information Authority (NSIA) in Daikundi said she heard about the planned reduction on the news and social media. She was at a loss to explain why women civil servants who did the same job as their male colleagues would have their salaries reduced:

We haven’t received any official letters … but I’ve heard on the news and also on social media that a decree has been issued to reduce the salaries of female staff. It’s really upsetting for us because we work as hard as [our] male [colleagues], so why do they want to reduce our salaries? This is discrimination against women. Today, the finance manager said a letter had come saying women’s salaries will be 5,000 afghanis from the month of Jawza [22 May-21 June]. I hope it’s not true. Instead of [giving us] an increase, they [plan to] reduce our salaries! They shouldn’t do it. Delays in paying our salaries are normal, but the work pressure is the same as it was in the past…. This news will cause women psychological difficulties.

A prosecutor in Kabul who goes to work every day said she had heard about the salary cut from the media and despite her colleagues’ reassurances that the order would not affect her, the threat of a reduction in her wages had left her acutely anxious:

I first heard the news through the media. Later, an order came to our office. But officials in the department said it can’t be implemented [because] the decree doesn’t have a wareda and sadera [date of receipt or execution]. Until the issue is clarified, [they said]: Don’t worry. But it did really worry me. A few days later, an official letter did come from the Ministry of Finance and made it clear that the salaries of those who stay at home would be 5,000 afghanis and those who come to work every day would have the same salary as before – there would be no changes in their salaries.

A midwife in Ghazni told a very similar story.

We haven’t been informed officially, but I heard from different sources and saw on social media that the government has decided to reduce the salaries of female employees. They’d already done it once [the December 2021 cuts to all employees’ wages] when they came to power and that’s already had its [ill] effects. People’s financial circumstances aren’t good. They can hardly manage to cover their daily expenses as it is. So, they shouldn’t reduce [our salaries] again.

If our interviews are any indication, the vagueness of the order’s wording caused a great deal of distress to female employees and their families, even those who might eventually discover they were not targeted for a wage cut. The fact that the order was not transmitted directly or officially to female employees, but was rather widely reported and discussed on media and social media, only exacerbated the confusion and concern.

Women in the public sector

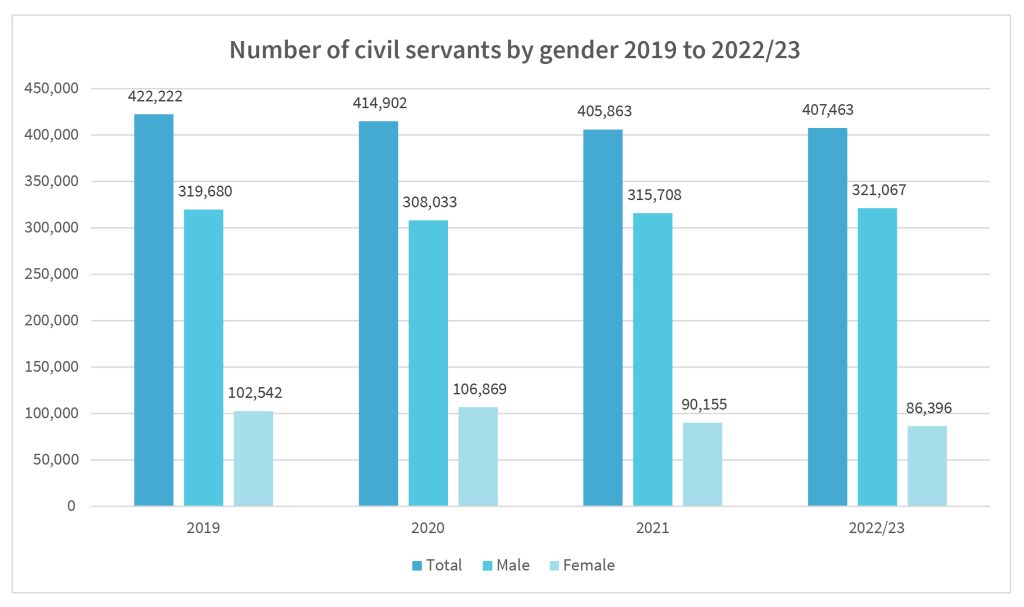

The public sector in Afghanistan has been the biggest employer of women in the last 20 years. Under the last government, the number of women working in both the public and private sectors had been rising, precipitated in part by the Republic’s plans and policies designed to facilitate their access to jobs and other economic opportunities.[6] In those years, 18.5 per cent of Afghan women participated in the country’s labour force, but only 13 per cent of those women were in salaried positions, mainly in the public sector.[7]

The proportion of women working in the public sector, Afghanistan’s biggest source of paid work for both men and women, has fluctuated over the last 20 years between 18 and 26 per cent. In 2005 and 2020, for example, women accounted for 26 per cent of public sector workers, but in every year between 2014 and 2018, as well as in 2021, they accounted for 22 per cent.[8] A year after the fall of the Republic, the proportion was still 21 per cent (this was measured for the Afghan year, then 1401, equivalent to March 2022 to March 2023).[9]

Far fewer women were ever employed in higher grade positions; see the 2020 data in the graph below as an example. Furthermore, women’s participation varied significantly between ministries, with women underrepresented in all ministries except the Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MoWA) and the Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled. The IEA abolished Women’s Affairs in 2021 and transferred most of its female staff in the provinces to the provincial Directorates of Vocational Training, which itself has recently been merged with the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

The total number of women working in the public sector under the Islamic Emirate remains elusive, with far higher figures than NSIA’s being reported by some government officials. For example, in its 23 July 2023 accountability session, the Ministry of Economy (MoE) said that “92,000 women work in the education sector and 14,000 in the health sector, they work in airports, banks, but as already mentioned, efforts are ongoing to prepare a suitable environment for women.” This would mean that some 106,000 women work in the education and health sectors alone, not taking into account women employed in other sectors. The figures are drawn from the AAN 2024 report ‘How The Emirate Wants to be Perceived: A closer look at the Accountability Programme’ (p 57). The same AAN report quotes the Ministry of Interior (MoI) saying that around 1,955 policewomen were serving in different fields and receiving salaries and the Ministry of Public Health reporting that women accounted for 22 per cent of its personnel (p 60).[10] It is not known, therefore, the potential number of women hit by the Amir’s order, but it is clear it is substantial.

Anxieties about an uncertain future

The abrupt nature of the Amir’s order put a spotlight on the precariousness of many Afghan women’s lives, in this instance, those working in the public sector. Their lives were already difficult, but they would have counted themselves among the lucky few who still had a regular income. Trying their best to keep their heads above water and provide for their families, this latest incursion on their right to a livelihood threatens to remove a safety net because, as one said: What can you do with 5,000 afghanis?

The quotes below reflect answers to the last question from our questionnaire: If there was a reduction in your salary, how would it affect the economy of your household, and your life? All interviewees said a salary cut would affect their lives dramatically. Many said they would have to leave their jobs because they could not survive on the reduced income. The midwife from Ghazni, for example, was concerned about how the anxiety was affecting their quality of work.

If someone is worried about their own life and expenses, how could they think about doing their job properly? People are already anxious about the news and, if it really happens, they’ll be hit hard. I’m the only person working in my family. No one else works because unemployment has increased. The cost of everything is very high – there’s the house rent, the electricity bill and other expenses. How can we manage if they reduce our salaries? They should have a thought for the people and if they don’t help or increase their salaries, at least, they should not reduce them.

Another midwife, from Kandahar, who sometimes gets paid by an NGO,[11] said she would leave her job if her salary was cut:

We hope the reduction won’t take place. We’re barely keeping on top of the necessities now. If the salaries are reduced, this’ll definitely harm the economy of our household badly. I’ll leave my job. So far, the salary [I get] from the NGO has supported our household. But if the NGO stops paying my salary and the government reduces my wages, I won’t go to the hospital even though leaving the job and losing even this 5,000 afghanis will badly affect my family’s finances, but it’s also very difficult to work full-time and do night shifts.

A policewoman from Kabul, who had already taken her son out of school so that he could work and help support the family, told us that if the Islamic Emirate really does reduce salaries, it will be extremely hard for women, especially widows like her who have no adult man to support them and are not qualified for any work other than their current occupation:

My son sells plastic bags because I can’t cover all the family’s expenses with my income. He has to work even though it’s not his time to work – he should be in school. He only makes 50 afghanis (USD 71) a day, with a lot of difficulty, and sometimes he can’t sell any bags. It’s been a month since he fell ill and we’re wondering what to do. The cost of living is very high and our income is low. 5,000 afghanis would only be enough for the rent and electricity. The taxi for me to go to and from work is expensive. Sometimes, I get sick and have no money to go to a doctor. 5,000 afghanis can’t cover all our expenses. I hope this is only a rumour or a lie and they won’t reduce my salary.

I ask the Islamic Emirate not to reduce the salary of any employee who’s working, whether she’s a policewoman, a doctor or a teacher. We’ve been serving our country. We carried on with the wages we got and lived with many problems. If they don’t increase the salaries, at least I hope they don’t reduce them.

The NSIA employee in Daikundi said that reducing the salaries of female civil servants amounted to an injustice:

If they really reduce the salaries of female employees, it will be a great disservice to women. It’s an injustice that’s done to them. Instead of reducing salaries, they should increase them because everything is expensive and we manage our lives with the wages they pay us. For example, from my salary, I pay 1,500 [USD 21] a month for the car fare to and from work. I also pay 1,500 afghanis a month for lunches. All our colleagues pay this much for lunches because the government doesn’t provide us with lunch and doesn’t pay for it either. My family is big and we have a lot of expenses. The price of goods has reached its peak. I spend 5,000 afghanis a month to buy flour, rice and oil. If the government pays us 5,000, we can’t do anything with it. It is really upsetting and so discouraging.

She appealed to the government:

We ask the government, if it has made such a decision, they should change it. Let us work in our country alongside men. Women work like men, so why should their income be reduced?

A teacher in Paktia said that all female teachers in her province were working because there was a teacher shortage:

The salaries that I and other teachers receive are very low and not enough for our families. We have teachers who are their families’ breadwinners. What can they do with a salary of 5,000 afghanis? They cannot meet their needs…. What should they do with their children’s school expenses, illnesses, food and clothes? These decisions cause problems for everyone.

She went on to talk about the plight of female public sector workers who have been forced to stay home since the re-establishment of the Emirate:

In general, all women [civil servants], whether they go to work or [have to stay] at home, should return to their duties because women have [only] stayed at home according to the decision of the Emirate. I have friends who are suffering immensely because they’re at home. They want to return to their duties. We need women in every department and they should pay the salaries of all women.

She went on to expand on the overall economic situation and compared the current circumstances for public sector workers to life and work under the Republic:

In general, the people’s economy has been badly damaged. People have become unemployed…. government offices are closed to women. Most of those who worked in the previous government are now unemployed. They’ve not been asked to come to their duties again. People’s purchasing power is weakened. Security is good, but security alone cannot change people’s lives…. Poverty and hunger can also kill people. Unemployment is a big problem that all people struggle with … but especially women. This recent decree regarding the reduction of women’s salaries will make their lives worse…. Under the previous governments, if the salaries were low, they provided other facilities for their employees. For example, they gave them coupons. The rents were lower, the price of goods was not so high and people could manage their lives with lower wages.

The prosecutor in Kabul talked about the entreaties of her female colleagues who are still forced to stay at home and came to the office only to sign their attendance sheets:

Many of them developed psychological problems when they heard their salaries were going to be reduced. Most are the only breadwinners of their families – they’re widows, or they don’t have anyone else [in the household] who can work, or they can’t find work. Every day, our colleagues call and ask what changes have been made regarding salaries. Just last week, our colleagues who had come in to sign [their attendance sheets] were crying and begging the head of our department to convey their message to the authorities not to reduce their salaries. You can’t do anything with 5,000 afghanis. They asked the head of our office to ask the authorities how women who are breadwinners can live with 5,000 afghanis.

The teacher in Farah said news of the salary cut had been a blow coming on top of the cost of transport to faraway locations where teachers had been transferred to:

Recently, there have been forced transfers. The IEA has forced some of us to go to teach in the districts and villages. They say: You should go and teach in remote areas; that is your jihad and if you don’t have a mahram, you should leave your job. A lot of women did leave their jobs because the locations were far away and they didn’t have a mahram. For women who teach far away [from their home] areas, 5,000 afghanis can’t cover even the car fare. What about their other expenses? Most women like me are the only breadwinners of their families because their husbands are unemployed now. It’s also natural that we get sick sometimes and we need to pay for doctors and medicine. How can we cover all these expenses?

A high school teacher from Mazar-e Sharif who, like everybody else, had already seen her salary reduced since the Emirate took power, was particularly bleak about the future:

My salary has already been cut and that has had an ill effect. My purchasing power has already weakened. It’s not my fault. They’ve forced us to stay home and not teach. Now, they’re going to reduce [the salary] again. They want us to die gradually, and that is all it is.

From being told to stay home to cuts in pay

Two days after it took power, spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid said that men and women would be working “shoulder to shoulder” in the Islamic Emirate.

The issue of women is very important. The Islamic Emirate is committed to the rights of women within the framework of Sharia. Our sisters, our men have the same rights; they will be able to benefit from their rights. They can have activities in different sectors and different areas on the basis of our rules and regulations: educational, health and other areas. They are going to be working with us, shoulder to shoulder with us. The international community, if they have concerns, we would like to assure them that there’s not going to be any discrimination against women, but of course within the frameworks that we have (see full transcript on Al Jazeera).

The pledge had been echoed earlier in the day by a member of the Taleban’s Cultural Commission, Enamullah Samangani, when he announced not only the IEA’s general amnesty for those who had worked for the Republic, but also that they were ready to “provide women with [the] environment to work and study, and the presence of women in different (government) structures according to Islamic law and in accordance with our cultural values” (see France 24).

A week later, the IEA appeared to change its stance: Mujahid said women should stay at home, the BBC reported on 24 August 2021: “Our security forces are not trained (in) how to deal with women – how to speak to women (for) some of them,” Mr Mujahid said. “Until we have full security in place … we ask women to stay home.” He called it a “temporary procedure.” Reports soon started emerging in the media that women working in government were being denied access to their places of work (see, for example, The Guardian on 19 September 2021).

In televised debates, in news and on social media, women raised concerns about their future under IEA rule and predicted that the qualifier “according to Islamic law and in accordance with our cultural values” would be used to deny them their rights as would the IEA refrain that they merely wanted to create an appropriate environment for women to be active in the workforce (see for example this 27 August 2021 Afghanistan International debate between the Republic’s last Deputy Minister of Education, Victoria Ghauri and a member of the Emirate’s Cultural Commission, Anamullah Samangani and this 10 September 2021 ToloNews Farakhabar programme with women’s rights activist, Tafsir Siaposh and Islamic scholar Abdul Haq Emad debating the right of women civil servants to return to work).

Finally, on 20 September 2021, the Emirate ordered women working for the government to stay home until further notice.[12] What emerged was a situation where most jobs previously filled by women were handed over to men and only those women whose jobs could not be carried out by a man, such as primary school teachers and health workers, were allowed to continue working.

The situation continued much the same until the recent order, although with greater pressure on women workers created by the Amir’s ban on women working for NGOs, international organisations and embassies issued in December 2022, the closure of universities to girls in the same month and the firming up of the ban on girls’ education beyond primary school. In the Accountability Sessions in summer 2023, there was even boasting about continuing to pay women who were at home, for example, by Director of the Secretariat of the Supreme Court Mufti Abdul Rashid Saeed:[13]

Despite these limits [imposed by foreigners, presumably a reference to sanctions], the Islamic Emirate continues to pay the salaries of all the employees who serve in the government. Women are at home, but the Islamic Emirate is dedicated to upholding their rights and according them the privileges they once enjoyed. Women continue to occupy the majority of office positions. In accordance with sharia, we grant women full rights.

Statements from various officials indicate that the plan to reduce salaries will affect only those women who have been forced to stay at home. The government’s motivation must be cutting costs. Pressure on the budget, which was only approved two months into the financial year, indicating a wrangling over the public finances, has been reported elsewhere, for example by the World Bank, which said in May that increased planned spending for 1402/March 2023-24 had left a budget deficit of 18.4 billion afghanis (USD 2.6 m). In earlier years since the Emirate took power, it said, quoting “anecdotal information,” the deficit had been covered by “treasury cash reserves left over from the republic era.” However, especially given the Emirate lacks borrowing options to finance its deficit, “the only viable strategies are to increase domestic revenues or cut unnecessary spending.”[14]

Cutting the wages of women compelled to stay at home may make budgetary sense and it is a relatively easy way, politically, to cut costs, given they are a group with little political clout or public voice. However, for the women themselves, the loss of income will be a heavy blow, especially as they have been forced to be economically inactive through no fault of their own. They feel they are left out in the cold. Moreover, it should be stressed that, nearly two months after news broke that the IEA planned the salary cap, there is still no official word about how it is to implement its plan and who, exactly, it applies to. Even if women fortunate still to be working in the public sector continue to be paid their salaries in full, the vaguely worded order and lack of clarity ever since has left them and their families needlessly racked with anxiety about the future.

Edited by Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | All English language translations are by AAN. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A budgetary unit is a state entity, such as a ministry, that by law can have allocations in the national budget, whereas non-budgetary units do not have explicit allocations in the national budget (budget codes) and are often, by not always, established for a specific time period and purpose. |

| ↑3 | The government of Afghanistan defines all government employees except military personnel as civil servants. |

| ↑4 | In December 2021, almost all government workers, male and female, saw their salaries cut by the newly re-established Islamic Emirate. University professors appeared to be the only group who received a pay rise. See Figure 6 on page 30 of this AAN 2023 report, ‘What Do the Taleban Spend Afghanistan’s Money On? Government expenditure under the Islamic Emirate’. |

| ↑5 | The Amir’s order followed another made in April 2024 that had abruptly abolished the government’s pension system. Since the fall of the Islamic Republic, retired public sector workers have not been paid their pensions. However, the Amir’s April 2024 order, which meant that pension contributions were no longer deducted from current workers’ salaries, signalled the unlikelihood that the state would start paying retirees their pensions ever again. See AAN reporting on the difficulties faced by Afghanistan’s public sector pensioners here. |

| ↑6 | These included the 2007-2017 National Action Plan for Women (NAPWA), the 2015 National Action Plan on Women Peace, and Security, and the 2017-2021 Women Economic Empowerment National Priority Programme. |

| ↑7 | The World Bank defines the labour force as comprising: “people ages 15 and older who supply labor for the production of goods and services during a specified period. It includes people who are currently employed and people who are unemployed but seeking work as well as first-time job-seekers. Not everyone who works is included, however. Unpaid workers, family workers, and students are often omitted, and some countries do not count members of the armed forces.”

The figures quoted in the text are from the Bank’s 2018 Afghanistan Issues Note: Managing the Civilian Wage Bill, which cited the 2013-14 Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS) that indicated that only 18.5 per cent of women were then participating in the labour force. “Within this small, employed population,” it said, “only 13 per cent of female labour is in salaried positions, suggesting that female participation in the civil service is an important anchor for female participation in formal sector salaried employment.” |

| ↑8 | The data is taken from figure 5 on page 12 of the World Bank’s 2018 Afghanistan Issues Note: Managing the Civilian Wage Bill; table 1 on page 2 of 2020 ‘Women’s Inclusion in Afghanistan’s Civil Services’, published by Organization for Policy Research and Development Studies (DROPS), as well as NSIA Statistical Yearbooks here. |

| ↑9 | See the NSIA Statistical Yearbook 2022/23, published on 5 February 2024. |

| ↑10 | In its 2023 accountability session, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MoCI) said it had provided 7,263 business licences in the previous year, 1,000 of which were to women. |

| ↑11 | In Afghanistan, sometimes an NGO pays teachers or health workers. When that happens, the government does not pay their salaries for the months they get paid by the NGO. Then, when the NGO stops paying, they go back onto the government payroll. |

| ↑12 | See ‘Tracking the Taliban’s (Mis)Treatment of Women’, published by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and an AAN report which scrutinised the legal basis for activists’ calls for the Emirate to be taken to the International Criminal Court over its policies on women and girls, ‘Gender Persecution in Afghanistan: Could it come under the ICC’s Afghanistan investigation?. |

| ↑13 | See pp 49-50 of the AAN’s How The Emirate Wants to be Perceived: A closer look at the Accountability Programme. |

| ↑14 | See the Bank’s May Economic Monitor. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign