Afghanistan Analysts Network

The first earthquake hit on 7 October at 11 in the morning, but there have been more earthquakes since. The earth hasn’t stopped moving for days. At first, people slept outside on the roadside, but then some people (whose houses were still standing) went back inside their homes. Unfortunately, another strong earthquake hit at night and they came rushing outside. Now, those who have tents are sleeping in them and those who don’t sleep in the open. People are panicked and afraid.

MASUMA JAMEH, A RESIDENT OF ZENDEJAN DISTRICT, 29 OCTOBER 2023.

Where were the earthquakes

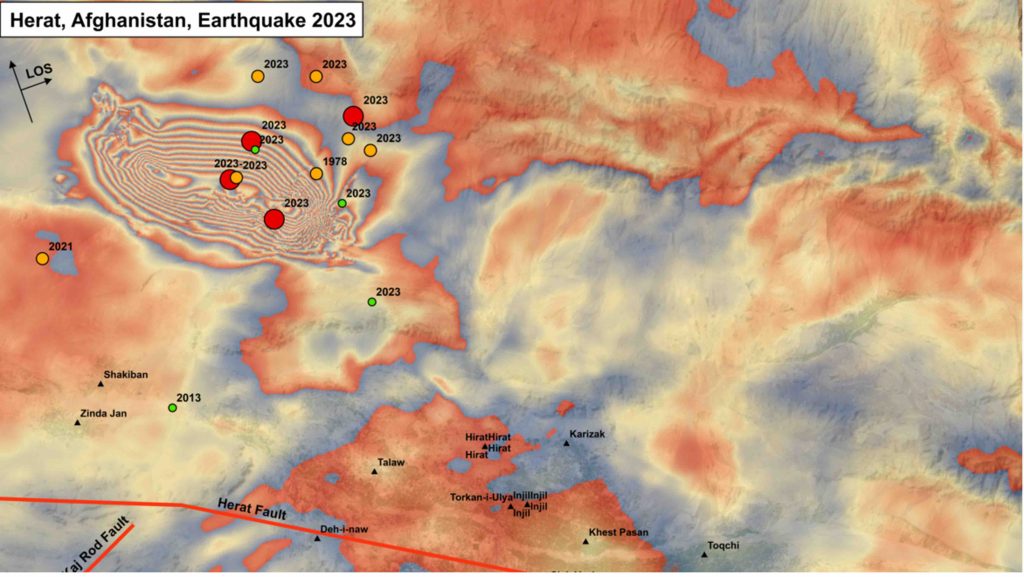

The epicentre of the 7 October earthquake, which measured 6.3 in magnitude on the Richter scale,[1] was in Zendejan district to the west of the provincial capital. About 30 minutes later, another 6.3 magnitude tremor hit the same area, followed by a third measuring 5.9. There have been no fewer than 35 aftershocks, all measuring 4 or above, as well as two more 6.3 magnitude earthquakes on 11 October and 15 October, according to data from the US Geological Survey (USGS).[2] In other words, the ground beneath people’s feet in Herat shuddered some 39 times in the span of three weeks. The dots in Figure 1 below, which uses InSAR satellite data, show the epicentres of quakes as of 10 October 2023, while the rings show where there were particularly strong changes to the earth’s surface.[3]

The Herat earthquakes happened on fault lines on the Eurasian Plate,[4] The Indian Plate is pushing north-north-westwards at a rate of about 38mm a year, while the Arabian Plate pushes north at a speed of 23mm a year. The result, wrote Afghan seismologist Zakaria Shnizai with three colleagues, is that Afghanistan is “one of the most seismically active intercontinental regions in the world,”[5] with active faulting distributed widely across it. The north is “cut through by numerous earthquake faults,” they wrote, while in eastern Afghanistan, active faults raised “the great mountain ranges of the Hindukush and Pamir.”

The epicentre of the October earthquakes in Herat was between the Siakhubulak Fault in the north and Herat Fault in the south, as well as a third hitherto unmapped fault line between these two, which was detected in satellite images, as reported by Earthquake Insights (see figure 3). The first two major quakes were in Zendejan district and the second two in Injil district, both about 30 km from Herat city.

The fact that these earthquakes were very shallow, about 10 km, is one of the reasons they had such devastating effects, according to the Helmholtz Centre Potsdam – GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, which also reported that a region measuring 20 km x 30 km around the epicentre had risen by about 40 cm (see here).

What astonished seismologists was that there were earthquakes in this location at all. On a geological timescale, wrote Afghan Seismologist Najibullah Kakar in the GFZ report cited above, the Herat Fault, which stretches across Afghanistan east to west, must have played an active role, but it had seen no earthquakes for a thousand years.[6] Another seismologist, Jascha Polet, who is professor emeritus at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, told National Geographic, “When the first two very similar magnitude 6.3 earthquakes occurred, I already thought that this was a fairly unusual sequence,” adding: “When the sequence then produced a quadruplet of these events, I was very surprised” (see here).

To understand what caused this unexpected quartet of tremors, National Geographic spoke to several seismologists. Some, such as the director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network at the University of Washington, Harold Tobin, have hypothesised that it was “most likely a domino effect”:

When the first quake struck on October 7, some of the stress from the geologic fault that slipped was transferred to another, already stressed fault. That caused it to rupture as well soon after –and this process happened twice more. This sort of transferal of stresses is seen all over the world, but in the case of these earthquakes, what’s unusual is that they have all been around the same magnitude and occurred in a very short period of time.

While most scientists agree with this theory, there are those who believe the earthquakes were a seismic event called a swarm, or a series of quakes of more or less the same magnitude happening around the same time and in the same region. Swarms of magnitude 6 or above are not common, Zachary Ross, a Geophysicist at the California Institute of Technology, told National Geographic, but he believes the ones in Herat were “fairly normal for earthquake swarms, in which we often see many earthquakes with similar magnitudes.”

Whatever natural phenomenon caused earthquakes, the absence of previous significant seismic activity in the region meant that residents, the government and humanitarian responders were caught off guard and were ill-prepared to deal with a disaster of this magnitude.

What do we know about the damage?

In its Herat Earthquake Response Plan (more on this later), which was released on 16 October 2023, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated:

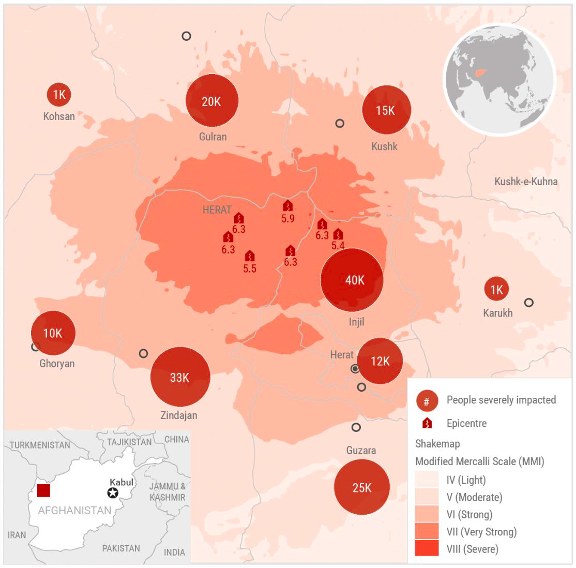

Between 7 and 15 October, four powerful (6.3 magnitude) earthquakes struck Herat Province, affecting 1.6 million people with high intensity shaking (MMI 6+)[7] and leaving at least 114,000 in urgent need of humanitarian assistance. Preliminary assessments show that the first two earthquakes on 7 and 11 October left 1,480 people dead and 1,950 wounded, with available satellite imagery indicating that 289 villages were very highly (11), highly (110) or moderately (168) impacted. An estimated 30 new villages across two districts were affected by the 15 October earthquake, with assessments ongoing.

Preliminary reporting by humanitarian responders estimated that 7,165 families were affected by the quakes (more than 43,000 people, based on an average of six persons per family) in six districts – Gulran, Herat, Injil, Kohsan, Kushk/Rabat-e Sangi and Zendejan (see OCHA Flash Update #6).

A later update, published on 2 November, put the number of households that have been affected at 48,000 in nine districts, mostly in Injil and Zendejan. It reports that some 48,000 household have been affected, including 30,430 houses either severely damaged (20,430) or completely destroyed (10,000), according to UNOCHA (see Afghanistan: Herat Earthquake Response Situation Report No. 2 here). The report also said:

More than 175,000 people in nine districts have been directly affected by these recent seismic events, with Injil and Zinjadan districts suffering the most severe consequences. Injil witnessed the destruction and damage of over 15,000 homes.

UNOCHA has also reported that 21,3000 non-residential structures, including 21 schools and 40 health facilities serving approximately 580,000 people, had also been damaged (see UN reporting here, here and OCHA Flash Update #7). Those affected included 7,500 pregnant women, many of whom were also bereaved (see this UN report). The extensive scale of the disaster means these figures are still likely to be adjusted upward as humanitarian teams continue to assess the damage.

• Initial multi-sectoral rapid assessments (MSRAF) indicate that more than 48,000 households have been affected by the recent earthquakes in Herat Province, including approximately 10,000 homes which have been completely destroyed and 20,430 severely damaged.

AAN spoke to Masuma Jameh from Zendejan district, who stressed how women and children were the prime victims of the earthquakes, but also that some children are now orphans:

Most of the casualties were women and children. Everyone is afraid, there is increasing anxiety and panic especially among women and children. The children are frightened every time the earth shakes. Also, hundreds of children are left without a parent or guardian. Their families were martyred [killed in the earthquake]. They need places to grow up and people to take care of them and look after their wellbeing and education.

Reports from the UN and others confirm her eyewitness testimony: women and children accounted for about 90 per cent of fatalities (see UNICEF here). Preliminary assessments of 178 villages that had been assessed as of 17 October 2023 found that women accounted for 58 per cent of adults who had lost their lives, 60 per cent of the injured and 61 per cent of persons reported missing, according to a report published by the Gender in Humanitarian Action (GiHA) (see Gender Update #2: Earthquake in Herat Province here).

The reason lies not just in the fact that many men from the region have gone to Iran for work, UNFPA’s representative in Afghanistan Jamie Nadal told the Associated Press, but also the time of the quake, 11 in the morning: “At that time of the day, men were out in the field…. The women were at home doing the chores and looking after the children. They found themselves trapped under the rubble.” AP also heard from the Norwegian Refugee Council which said that, “Early reports from our teams are that many of those who lost their lives were small children who were crushed or suffocated after buildings collapsed on them.” Increasing the casualties, said head of UNICEF’s office in Herat Siddig Ibrahim was that, “When the first earthquake hit, people thought it was an explosion, and they ran into their homes.”

The Herat maternity hospital has also sustained significant damage, with cracks that make it unsafe to provide services inside. The UN has provided tents for pregnant women to receive medical care (see CNBC here). Herat’s exquisite blue mosque and the Citadel, which dates back to 330 BCE, also suffered (see Xinhua reporting here). Indeed, said the head of the province’s Department of Information and Culture Ahmadullah Muttaqi, “There are no historical monuments in this province that were not damaged by the earthquake” (see this Salam Watandar report and these photos posted on X, formerly Twitter).

The earthquakes damaged several reservoirs, which are important sources of water and also caused the water table to rise in some areas. There are anecdotal reports that in Herat it has risen by 10 to 15 metres, architect Jolyon Leslie, an architect working on the restoration of historic monuments and is a long-term resident of Afghanistan, told AAN on 2 November: “It’s not unusual for aquifers to open up and come to the surface after an earthquake when the plates adjust.” Managing director of the media organisation, The Killid Group, Shahir Zahine, who had just returned to Kabul from Herat on 1 November, also confirmed these reports and said that there were reports of streams and other surface waters in locations that would not ordinarily see water at this time of year. The photo below, sent to AAN by Zahine, shows a wadi near Siah Ab village in Zendejan district; the water has appeared unexpectedly and out of season.[8]

In a crushing turn of events, on 12 October, a sandstorm in Zendejan, Kohsan and Kushk/Rabat-e Sangi districts, which lasted for 24 hours, destroyed several hundred tents where survivors had been sheltering, including 60 per cent of those at the Gazergah Transit Centre (GTC) (see OCHA Flash Update #5 and these photos on the Indian magazine Outlook’s website). The storm had another unlucky consequence: “People took refuge from the storm inside buildings,” said Masuma Jameh. “Unfortunately, another strong earthquake hit at the same time as the storm and many more people were killed and injured.” Rescue operations continued after the storm ended, as a local journalist, who asked not to be identified, told AAN on 28 October:

The tents that had been given to the people couldn’t withstand the storm and those who were providing aid had to stop working for a time. As soon as the storm stopped, people started helping again. Around this time, special tools arrived and rescue dogs came from Uzbekistan. They searched and pulled many people out from under the ground – alive or dead.

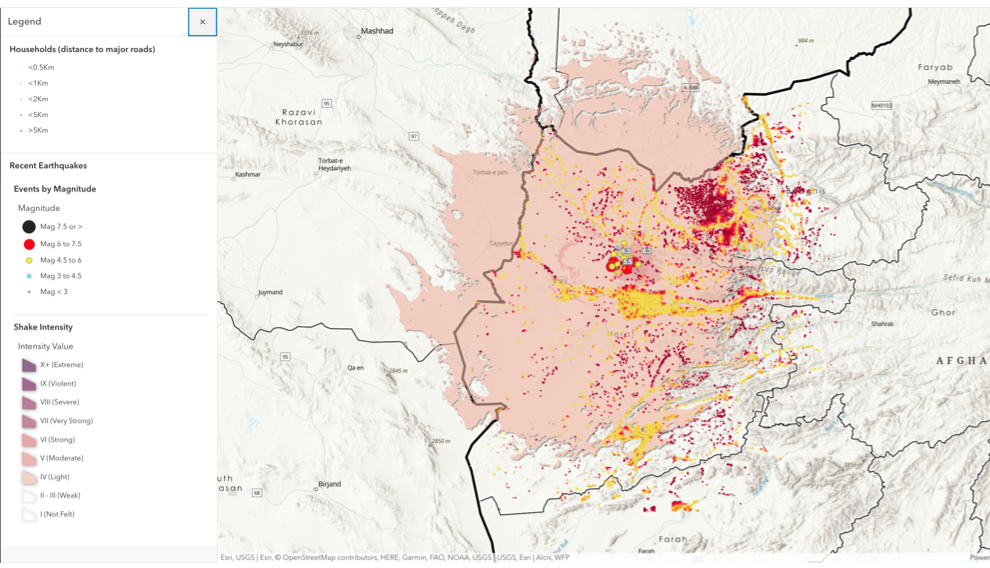

Satellite imagery analysed by the Geographical Information Services (GIS) organisation Alcis has provided a more comprehensive picture of the extent of the quakes and the complexities associated with the response (see Figures 5 and 6.) According to Alcis estimates, based on its analysis of satellite imagery, the number of people affected by the October earthquake could be significantly higher than preliminary estimates reported by UNOCHA and the Emirate. It estimates that as of the earthquake on 15 October (which Alcis counts as the third), a total of 512,992 compounds (residential dwellings) were affected. “Working on the assumption there are an average of 10 people per household,” it calculated that more than five million people – or about 12.5 per cent of the Afghan population – have been affected by the earthquakes. It also said that 160,706 of the household compounds were located more than four kilometres from a main road, meaning many communities had, at the time of the report, not yet been reached for assessment or assistance.

The level of destruction in Herat province, especially by earthquakes classed as ‘moderate’,[9]) can be attributed, in part, to the nature of most structures in the area, according to seismologist Zakaria Shnizai speaking on the BBC’s Science in Action:

The houses [are] mostly of adobe construction with traditional building materials, flat or domed roofs made of dry mud which is supported by timber sitting on walls of mudbricks or stone blocks, cemented with dry mud…. [T]hese buildings are suited actually with Herat’s climate conditions including the cold winter and the hot summers…. The proximity of active faults when combined with traditional building styles make active villages very susceptible to even moderate earthquakes in the area.

The architect, Jolyon Leslie, acknowledges that traditional adobe constructions are more susceptible to earthquakes and that the dust from collapsed or damaged structures, which suffocates victims, has contributed to the high number of fatalities. Nevertheless, he argues that with proper reinforcement and the use of better fortifications, these structures remain the most appropriate options for housing in the area:

There’s a reason why the houses are built this way. Mud brick structures are cool in the summer and warm in winter, which is exactly what’s needed in this arid region. They do need to be better reinforced to withstand earthquakes, but I really think they’re the right structures instead of the modern prefabricated housing that is usually the default solution after natural disasters. Sure, they are easy solutions that are quickly delivered, but will people use them in the long term? With some support and technical assistance, people could build mud brick houses themselves and this could also create short-term jobs and put money back in the economy.

What has the response been?

Earthquakes are notoriously difficult to respond to. They happen suddenly and, most often, without any warning. They destroy homes and infrastructure, such as roads and disrupt communications, all of which hampers efforts by first responders and relief workers scrambling to get to the area. Rescuers are left working against the clock to pull survivors to safety from the rubble. Affected communities are devastated, shocked and stricken by grief, homeless and many with livelihoods also destroyed. All this was the case in Herat, as the local journalist described:

On the first day, there was little help for the people because Zendejan district is almost two hours away from Herat city by car. Most of the homes in the area were traditional mudbrick houses and none were left standing. No houses. The phone networks were down and it was difficult to get any information in or out. It was only on the second day, when news spread of the devastation, that members of the public and the local authorities started arriving. People were left to rescue family and neighbours in their own village and couldn’t go to the aid of people in other villages. And anyway, they were so consumed by the destruction in their own village that they couldn’t imagine that the same thing had also happened in other places.

In some villages, no one’s left alive and the living are either consumed by grief for their [lost] relatives or tending to injured family members. Most of the wounded have been taken to the hospital in Herat city. That first day, the public, the government and the institutions did not go to the rescue of the people. When help arrived the next day, [in many villages] there was no one left to guide [the rescuers] and because the houses were mostly destroyed, it wasn’t clear what was where and who was missing or needed help. The late arrival of assistance and the absence of locals to guide rescue teams contributed greatly to the high number of casualties.

In such times, it is often community members and ordinary citizens who rush to the aid of their neighbours. Local residents speaking to ToloNews told of how people from elsewhere in the province and further afield rushed to their villages to lend a helping hand (see ToloNews’ extended coverage here). Nearly everyone we spoke to told us about the extraordinary public response,[10]) including the local journalist:

There have been a lot of donations. Everyone’s helped as much as they could. And a lot of help came from Herat city and other provinces as well as from the local administration. They’ve been providing food, tents and other necessities.

Jolyon Leslie also told us how labourers on a historic site that is being restored responded to a call for help:

The public response has been really impressive. This isn’t surprising in Afghanistan where people show up to help each other. This time, the general public and also the private sector have really mobilised to help. The next morning after the earthquake, local officials went door to door to all the NGOs and asked what they could do to help. They came to us too and 70 of the men working on the site volunteered to go. They helped find survivors and dig graves.

Domestic response

The Emirate was quick to respond to the disastrous events in Herat province by sending search and rescue teams and an official delegation to survey the damage. The morning after the first two earthquakes, the spokesman for the Ministry of State for Disaster Management, Janan Saiq, gave a detailed account of the Emirate’s immediate response at a press conference. 35 teams, made up of more than a thousand people, had “gone to the site to help those trapped in villages under the rubble,” he said (see ToloNews here and an interview with Saiq on the channel’s Farakhabar programme here). He also said that acting Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar was already in the province, heading a delegation of officials who included the provincial governor and officials from the Ministries of Economy, Refugees and Repatriation and Disaster Management, tasked with “addressing the challenges of earthquake victims and monitoring the fair distribution of aid.”

Saiq initially put the number of fatalities at over 2,400, later revised down to 1,000, with more than 2,000 people injured (see this Reuters report). He also estimated that 1,320 houses had been totally destroyed.[11]) A significant number of livestock were also lost in the earthquake, he added, but could not provide exact figures because the Emirate was focusing on rescue and relief efforts. These included providing water and sanitation, food and shelter. Acting Minister of Public Health, Qalandar Ebad, told ToloNews that nearly 60 health teams had been sent to the area, with “ambulances… and in every team of doctors, there are nurses and midwives who provide services for women.”

In an emergency cabinet meeting on 8 October, acting Prime Minister Mullah Muhammad Hassan Akhund ordered 100 million afghanis (USD 1.35 million) to be allocated for cash distributions to earthquake victims and appointed a special cabinet-level commission to oversee relief efforts.

The commission, which is comprised of the ministries of rural reconstruction, defence, interior, public health, disaster management and the Afghan Red Crescent Society, is “responsible for ensuring that everyone gets the help it needs and that there is no corruption involved,” Emirate Spokesman member Zabiullah Mujahid told DW (see here).[12]

The Emirate has also suspended the required administrative hurdles that are a requisite for NGO operations, an aid worker told the UAE’s English-language daily The National:

We don’t need any of the usual permits to do our relief work in the earthquake-affected areas…. Normally we face a lot of challenges and restrictions – getting permission can take up to four months. But the DFA [de facto authorities] recognises the seriousness of the situation. They have just asked us [international aid groups] to co-ordinate our activities with one another.

The only challenge we have faced is the DFA’s requirement that no female staff are allowed to work in the disaster area without a male escort. But we are very familiar with this restriction by now, so we were well prepared.

The Emirate is also building “2,146 modern houses in 20 affected villages,” which it hopes to complete before the onset of winter (see Tolonews here and BBC Pashto here). Shahir Zahine told AAN that he had seen some of the houses being constructed during his visit: “I’m not an expert in architecture, but they are building the houses quickly and the material being used seems to be of good quality.”

Zahine said he had travelled to the province to check on the well-being of the organisation’s staff –the building housing The Killid Group in Herat had been destroyed – and see what Killid could do to support the victims. It has now set up three mobile radio stations in the most affected districts (Gulrun, Rabat-e Sangi and Zendejan). During natural disasters, when means of communication are largely down, radio remains the most vital source for quickly disseminating up-to-date, accurate and lifesaving information to the public (see the UN’s International Telecommunication Union (ITU) here).

International response

UNOCHA launched an appeal on 16 October on behalf of UN agencies and NGOs, requesting 93.6 million USD to support some 114,000 people. The plan will focus on supporting those whose homes were severely damaged or destroyed for six months (October 2023 – March 2024). It clarifies that the emergency appeal’s activities and requirements are a sub-set of the 2023 Humanitarian Response Plan.

As Figure 7 shows, according to the Plan, over the next six months, aid organisations will work with local and national government officials to support the most vulnerable people in affected communities on a whole range of needs: “emergency shelter and basic household items; provision of trauma care, referrals to the medical facilities, provision of the medical kits/supplies and equipment, as well as mental health and psychosocial support services; therapeutic and supplementary feeding for those acutely malnourished, as well as malnutrition screenings; dignity kits; water trucking, latrine construction and hygiene kits; as well as food commodities and cash packages” (for a detailed breakdown by sector, see the Herat Earthquake Response Plan).

In the days following the earthquakes, several UN agencies launched separate appeals to mobilise funds for the victims of the Herat earthquakes in support of their earthquake response activities, including WFP (USD 19 million), UNHCR (USD 14.4 million), UNFPA (USD 11.6 million) and UNICEF (USD 20 million).[13] Several national and international NGOs have also launched appeals to raise funds for their planned responses to the earthquake. However, as Figure 8 shows, the response has, so far, fallen significantly short of the appeal, only USD 30 million (USD 15 million from donors and another USD 15 million from humanitarian pooled funds) or about 33 per cent of the amount needed to support survivors for the next six months (see the table below for a breakdown of pledges made and assistance provided so far).[14]

The aftermath

The view from the ground is that assistance to the victims of Herat’s October 2023 earthquakes is, as yet, not nearly enough.

Aid has been distributed, Including tents, food, hygiene and other necessary items, but it’s not enough. Many people have lost their entire family and their houses have been razed to the ground. They have lost everything. Entire villages have been turned into dust. Most of the aid is from businessmen and from people from different provinces, Afghans living abroad and also some charities. Most of the work is being done by civil activists, especially women. From time to time, there are aid distributions from members of the public, but assistance from the government and international institutions has been slow to arrive.

MASUMA JAMEH, A RESIDENT OF ZENDEJAN DISTRICT

The local journalist we spoke to said the most pressing concern was the weather: “It’s getting colder every day and those who’ve lost their homes need shelter. They can’t go on living outdoors for very much longer.” Winters are harsh in this semi-arid region of Afghanistan, with overnight temperatures regularly falling to below freezing. Last year, Afghanistan witnessed the harshest winter in nearly 30 years, with temperatures falling in this area to below minus 25 degrees Celsius, according to UNOCHA (see here).

There are numerous photos and videos in news reports and on social media showing tents among the rubble heaps that were once villages. Matters are especially bleak in Herat city where many survivors, with nothing left in their home villages, have gone in search of shelter and other support. The provincial capital is now “a tent city: families are sleeping in open spaces in parks in small tents,” wrote the Director-General of the World Health Organisation, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in a post on X on 16 October. The local journalist also described the scene to AAN:

The parks and streets of Herat city are filled with people who’ve arrived from the districts and also [the city’s] local residents. Those who have houses go home every day, but people aren’t spending the night there. They sleep on the street outside their houses or in parks or on pavements. Since the day of the earthquake, many people have been leaving Herat for Kabul and other provinces, but there is a shortage of cars [for hire], so it’s not easy to secure transport. The situation is very worrying because it’s so cold. Some people have tents, but most don’t and are forced to sleep in the open air in the cold. There are no tents for sale in the market, but some people have managed to find tarpaulin and plastic sheeting. Women and children are sleeping outside in the open during these cold nights. Many of them, especially the children, are sick with colds and more serious chest infections.

While there are plans underfoot by the Emirate to build over 2,000 permanent homes for Herat’s earthquake victims, aid workers are doubtful that such a massive undertaking will be completed in time to protect them from this winter’s freeze. They point to their previous experience in other disaster zones and argue for urgent distributions of winterised tents and assistance to help victims either rent housing or find shelter with host families.

The psychological fallout from the disaster is also significant. Not only have people lost their friends and families, their homes and their livelihoods, but the ground has been moving under their feet for the better part of a month. Many people whose homes have remained undamaged are fearful of being indoors when the next earthquake hits:

People are afraid to sleep indoors. They’re afraid of what might happen if a quake hits when they’re sleeping. So even those whose homes are still standing sleep outside. It’s remarkable to see how the number of tents swells up in the evenings. All open spaces – parks, the courtyards of mosques, even highways – fill up with tents. Families who don’t have proper tents use makeshift ones made of mosquito netting. In the morning, those who still have a house, take down their tents and go home – only the ones who have come [to Herat] from the districts or have lost their house stay.

SHAHIR ZAHINE, MANAGING DIRECTOR OF KILLID GROUP

It is not just the damage and loss of life from the earthquake that is a big worry. Money is also an ongoing concern. After the dead have been buried and the injured tended to, after survivors have been provided with adequate shelter and basic services such as health care and education, after provision has been made for the children who have lost their family, after all that, the government and aid organisations must turn their attention to making sure affected communities have appropriate support to rebuild their lives and get back on their feet. Local communities who have lost not only their homes and families but also farms, livestock, jobs and businesses need help to rebuild their lives, rehabilitate their farms, find jobs and restore at least some of what they lost in the disaster.

Edited by Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | According to the Richter Scale that measures earthquakes, those measuring 6.0 to 6.9 are considered ‘strong’ and 5.0 to 5.9 ‘moderate’ quakes. A 6.3 earthquake like the ones in Herat is capable of causing considerable damage to “ordinary substantial buildings with partial collapse” and “great damage in poorly built structures poorly,” according to this explainer on the Puerto Rico Seismic Network. Most well-built structures can withstand a 5.9 magnitude tremor, it says, but poorly built, weaker structures can sustain considerable damage. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In reporting the number of quakes and aftershocks, we are using data from the US Geological Survey (USGS) (see here). There are conflicting reports about the number of earthquakes with many, including the United Nations, reporting that four earthquakes took place. However, the region experienced 28 magnitude 4.1 or above aftershocks, which means that there were a total of 32 tremors in 7-19 October. |

| ↑3 | InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) is a technique for mapping ground deformation using radar images of the Earth’s surface that are collected from orbiting satellites (see USGS here). |

| ↑4 | The Earth’s rigid outer shell is fractured into seven or eight major plates and many ‘platelets’ which all slowly move.) the world’s third largest tectonic plate (67,800,000 km2) which spans Europe and most of Asia and sits between the North American and African Plates to the north and west, as well as many smaller ‘platelets’ (see figure 2). All of them are slowly moving. Afghanistan lies on “a southward-projecting, relatively stable promontory of the Eurasian tectonic plate,” wrote Boyd, Mueller and Boyd, but is surrounded by “active plate boundaries” to the west, south and east.(( Oliver S Boyd, Charles S Mueller and Kenneth S Boyd, ‘Preliminary probabilistic seismic hazard map for Afghanistan’, 2007, US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1137. |

| ↑5 | See Zakaria Shnizai, Morteza Talebian, Sotiris Valkanotis and Richard Walker, ‘Multiple factors make Afghan communities vulnerable to earthquakes’, 2022, Temblor. |

| ↑6 | There have been there have been ten magnitude 6.0 or greater earthquakes in Iran’s Khorasan province bordering Herat (see Wikipedia for a list of earthquakes in Iran), including the 7.3 magnitude Qayen earthquake in May 1997 (see USGS here) and the 7.1 tremor in September 1978 (see USGS here), which claimed some 15,000-25,000 lives (an estimated 80 per cent of the local population) and all but destroyed the historic city of Tabas and 90 surrounding villages (see ‘The 1978 Tabas, Iran, earthquake: An interpretation of the strong motion records,’ Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 1988, 78 (1), 142–171. |

| ↑7 | The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MMI) measures the effects of an earthquake at a specific site using “key responses such as people awakening, movement of furniture, damage to chimneys, and finally – total destruction…. [It is considered to be] more meaningful measure of severity to the nonscientist than the magnitude because intensity refers to the effects actually experienced at that place” (see USG here). |

| ↑8 | A wadi is a valley or ravine that is dry except in the rainy season. |

| ↑9 | See footnote 1. |

| ↑10 | In addition to the numerous media reports and videos on social media also show members of the public helping with the rescue, there are also reports of Afghans inside the country and abroad responding with cash and in-kind donations (see for example ToloNews here and here, as well as this Deutsche Welle report). The private sector and celebrities have pledged support for the earthquake victims. For example, Afghanistan’s star cricketer, Rashid Khan, donated all his earnings from the 2023 Cricket World Cup and has launched a campaign to raise additional funds (see his post on X, formerly Twitter here). |

| ↑11 | While this figure is considerably lower than the numbers reported by other sources, including the UN, such inconsistencies are not unusual, especially in the days immediately after a natural disaster. It is often in the days and even weeks afterwards that a full picture emerges of the extent of the damage. |

| ↑12 | Several line ministries have announced donations from staff members to support victims of the Herat earthquakes, including the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) 24 million Afs (USD 325,000) from their salaries; Ministry of Education 11.34 million Afs (USD 153,000); and Ministry of Defence 36.57 million Afs (USD 494,000). |

| ↑13 | WFP’s USD19 million appeal will assist earthquake victims with food and cash-based transfers for three to seven months. Earlier this year, WFP was forced to reduce the amount of food families receive and to cut 10 million people in Afghanistan from life-saving food assistance due to a funding shortfall (see here). UNHCR has also launched an urgent appeal for USD 14.4 million to support some 8,100 earthquake-affected families, including refugees and IDP returnees, with tents, cash assistance, psychosocial and cash support and other relief items. UNHCR also plans to support orphaned, separated or unaccompanied children and persons with special needs, such as the disabled and the elderly (see here). UNFPA has asked for USD 11.6 million to support women and girls in the earthquake zone with maternal, reproductive health and psychological services; life-saving adolescent sexual and reproductive health services; and emergency supplies, including health, mother and child, dignity and menstrual kits as well as non-food items such as blankets and tarpaulin sheets for women and girls (see here). UNICEF has also launched an appeal asking for USD 20 million to support 200,000 beneficiaries, including 96,000 children with health, psychological and hygiene services, water and sanitation, cash assistance for 1,400 families and temporary learning spaces for children (see here). |

| ↑14 | According to media reports the Emirate declined an offer of assistance from Pakistan (see Khaama Press here and VoA here). |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign