Afghanistan Analysts Network

In total, the US rendered 780 prisoners to its detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, of whom 225 were Afghan. Out of that number, 221 have been released, among them Taleban military and civilian officials, but also shepherds, taxi drivers, shopkeepers, tribal elders, anti-Taleban leaders, abused boys and old men with dementia. Three Afghans died in Guantanamo. One remains.

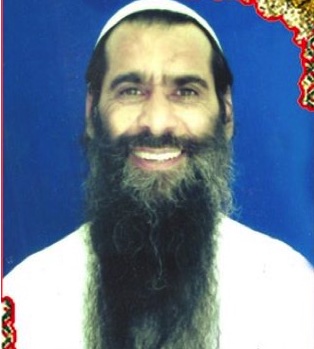

Muhammad Rahim was the last Afghan to be taken to the prison camp, indeed the last detainee of any nationality to be rendered there, and the last man known to have passed through a CIA black site. The torture he endured was documented in a 2014 report by the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence into the CIA’s use of rendition and torture.[1] The fact that the US has kept this individual for so long and has wanted to detain him even after ending its war in Afghanistan is, as this report will show, mystifying. Rahim is currently waiting for a Periodic Review Board hearing, when a group of military, intelligence and civilian government officials could decide to release him or continue to detain him (or a third, largely theoretical possibility at this stage, send him for military trial). The hearing was scheduled for May, but was abruptly cancelled at the last minute and rescheduled for 15 August.

Before looking at Rahim’s case and his prospects at the upcoming Periodic Review Board hearing, the author first considers the report of the first independent UN investigator to visit Guantanamo. The report is replete with details of the “horror and harms” done to the hundreds of Muslim men and boys who were rendered to Guantanamo in the wake of the 9/11 attacks on the US, and has implications for both Rahim and the other Afghans taken there.[2]

The “horrors and harms” of Guantanamo

Special Rapporteurs are appointed by the Human Rights Council but serve in their personal capacity. This is evident in the direct language of this report by the Irish academic lawyer, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism. She writes of how detainees were “rendered across borders, forcibly disappeared, held in secret detention, and subject to egregious human rights violations” by the United States in the years after the 9/11 attacks. The “vast majority” she notes, were “brought without cause and had no relationship whatsoever with the events that took place on 9/11.” They were subject to:

[W]aterboarding, walling, deprivation of food and water, extreme sleep deprivation, and continuous noises while in detention…. violently slapped, shaken, subject to mock executions, kicked, thrown to the ground, and held in solitary confinement for months … told that multiple serious harms would befall their family members including physical violence, economic distress, and social shaming … [and were] subject to sexual violence, including anal penetration.

Ní Aoláin writes that: “Every one of the 780 Muslim men [and this author would add ‘and boys’][3] who was held at Guantánamo Bay” lived or still lives “with their own distinct experiences of unrelenting psychological and physical trauma of withstanding profound human rights abuse.” Detainee families, she says, have also “suffered immeasurably.”

The rendition, secret detention, torture and ill-treatment at multiple sites and at Guantanamo Bay was, she says, “structured, discriminatory, and systematic.”

The US government, she writes, “authorized and justified, and personnel enabled and sustained [the detainees’] torture.” Ní Aoláin underscores that the prohibition on both torture and arbitrary detention are jus cogens, one of several absolute principles of international law from which no state can exempt itself, nor make ‘legal’ through domestic legislation. Up to now, she emphasises, “there has been no adequate accounting of the international law violations including violations of jus cogens norms that occurred from September 11, 2001 onwards.” She underscores that the US government has “an ongoing obligation to investigate the crimes committed at Guantánamo, including an assessment of whether they meet the threshold of war crimes and crimes against humanity.” As part of that investigation, she says the US government is under a continuing obligation to:

[S]anction those responsible [for any violations], provide appropriate redress and reparation to all victims and adopt effective guarantees of non-repetition, such as legislative, administrative, judicial, and other measures to prevent and punish such violations going forward.

Ní Aoláin insists that: “The world has and will not forget. Without accountability, there is no moving forward on Guantánamo.” However, as things stand, it is impossible to see a US administration compensating victims of Guantanamo or apologising to them or prosecuting its own officials. Up to now, the US has only investigated individuals accused of using unauthorised interrogation techniques and even then, investigations have been administrative, rather than criminal, and into low-ranking officials, with any punishments limited to disciplinary actions, even when detainees were killed. Those ordering and sanctioning the breaches have remained untouched by the law.[4] Indeed, ahead of the publication of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s 2014 report into the CIA’s ‘detention and interrogation programme’, while Barak Obama acknowledged, for the first time by an American president, that the US had used torture, he also downplayed it, effectively ruling out prosecutions:

It’s important for us not to feel too sanctimonious in retrospect about the tough job that those folks had. And a lot of those folks were working hard under enormous pressure and are real patriots.[5]

As to non-domestic forums for accountability, the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan, has decided to ‘de-prioritise‘ the alleged war crimes of the CIA and US military in relation to the war in Afghanistan, along with those of the forces of the Islamic Republic, and instead focus on accusations against the Taleban and Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) (for more on what AAN called his creation of a ‘hierarchy of victims’, see our report from 11 November 2022). The move by the prosecutor followed a period of significant intimidation of court staff by the United States under President Trump, as well as a long history of US belief in its exceptionalism, when dealing with the International Criminal Court.

The Special Rapporteur has much to say in her hard-hitting report about what could be done to make the regime in Guantanamo less unbearable for its current 30 inmates, whom she insists “must be treated with humanity and respect for their inherent dignity in line with the U.S. Government’s international legal obligations.” Recommendations range from better facilitation of communications with families to improving medical care, including treating ongoing medical conditions resulting from torture, to calling detainees by their names rather than their Serial Internment Numbers. However, as one detainee explained to her, “the conditions of confinement” have already improved since they were first brought to Guantanamo, but “the legal conditions are worse than ever.”

Ní Aoláin’s conclusions on the various judicial and administrative review mechanisms are, indeed, excoriating. On the Periodic Review Board, which decides the fate of detainees (transfer, continue to detain or send for military trial), she says:

The Periodic Review Board process lacks the most basic procedural safeguards, including because the process is a purely discretionary proceeding that is not independent and that is subject to veto by the political officials on the review committee. Further, the fact that 16 men have been cleared yet remain trapped in the Guantánamo detention facility is indicative of the Periodic Review Board process’ disconnect from any actual release and the arbitrariness of the cleared men’s ongoing detention.

On detainees petitioning courts on the US mainland for habeas corpus – when the government has to convince the court that the detention of an individual is lawful, or release him or her, she says:

Regarding habeas remedies she finds it has been overwhelmingly ineffective both in efficiency of process and delivery of the remedy of actual release for detainees. Detainees have had access to habeas corpus since 2004, but most proceedings have languished in judicial pipelines undermining the requisite regularity of independent, impartial, review, and calling into question their effectiveness as a matter of international human rights law.

As to the ongoing trials by military commissions, she points to their “fundamental fair trial and due process deficiencies,” noting that:

[N]ine men involved in the military commission process are still in the pretrial phase after experiencing countless delays. As one detainee interviewed expressed with exasperation, the system is paralyzed but their only option is to engage. The defendants in the September 11 case were arraigned in May 2012, with pre-trial hearings suspended through at least early 2023. The endless delays in their cases, and the U.S. Government’s failure to even move past the pre-trial phase clearly fail to meet the “undue delay” threshold. She further expresses serious concern that the military commission hearings have been inundated with an array of procedural obstacles and legitimacy challenges, ranging from issues with interpretation –including due to alleged bias and lack of independence and impartiality – and significant technological failures in the courtroom, to abrupt prosecutor and judge retirements and resignations and conflicts of interest.

In every aspect of life at Guantanamo, the Special Rapporteur reports of “cumulative and unrelenting” arbitrariness, uncertainty and the powerlessness of detainees. The longer a situation of detention lasts, she says, the higher the likelihood that the prohibition of torture, cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment has been breached. In this, the case of the last Afghan held in Guantanamo, now waiting for his latest Periodic Review Board hearing, is illustrative.

Rahim’s case

Muhammad Rahim is one of three men still held in Guantanamo whom the US has not sent for military trial but continues to hold in indefinite detention because it deems them a risk to US security. He was detained by the Pakistan intelligence agency, the ISI, in 2007 and handed over to the CIA, which held and tortured him at a black site in Afghanistan before rendering him to Guantanamo in 2008.

Rahim, an Arabic speaker, has admitted to working with Arab fighters before and just after 2001. This was not in itself unusual or pointed necessarily to any shared ideological stance; getting paid employment was much sought after in this very poor country. The US military had previously claimed the job of another Afghan detainee, Abdul Zahir, for example, who had worked as a chokidar (doorman) and occasional translator for an Arab commander, was sufficient to detain him from 2002 to 2015, a position later overruled by a Periodic Review Board. When it was finally decided he could be released, the review board said he “was probably misidentified as the individual who had ties to al-Qaeda weapons facilitation.” (For detail on Zahir’s case, see pages 30-33 of the author’s 2016 special report, Kafka in Cuba: The Afghan Experience in Guantanamo.)

The US asserts – and Rahim denies – that he also cooperated with al-Qaeda beyond the immediate post-2001 era. The CIA told the press when it announced his detention that he was one of Osama bin Laden’s “most trusted facilitators,” “a tough, seasoned jihadist” who was “best known in counter-terror circles as a personal facilitator and translator” for bin Laden. It has asserted that Rahim was an al-Qaeda courier who personally transported “tens of thousands of dollars” for the alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Muhammad, travelled to Iran to help the leader of Hezb-e Islami, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar come back to Afghanistan and coordinated “the movement of bin Laden’s wives and families.”

These claims have never been independently scrutinised or robustly questioned, for example, by an independent court of law. Moreover, they are difficult to square with what was revealed in the Senate’s 2014 report on the CIA’s use of torture, which revealed that the CIA’s interrogation of Rahim had “resulted in no disseminated intelligence report.” It suggested that the only information it had about him were the ISI’s allegations and nothing useful was ascertained from the interrogation.[6] Documents released in Rahim’s habeas petition also point to the basis of US accusations being hearsay, including ‘double hearsay’, ie what someone claimed someone else said about Rahim, testimony from detainees obtained under torture or duress, and unverified and unprocessed intelligence reports. Research by this author into other similar claims against other Afghan detainees point to a continued pattern of accusations that are fantastical, nonsensical and lacking in factual basis (see the ‘Kafka in Cuba’ report cited above and the detailed investigations into the cases of the last eight Afghans held in Guantanamo, including Rahim, for more on this).

The US classes Rahim as a ‘high-value’ detainee, as it does all the men who were held in CIA black sites, rather than detained by the US military.[7] Over time, it has become clear that this classification was given not because of their supposed high risk or high intelligence worth, but to protect the CIA: the label ensured detainees were kept in secrecy, segregated from other detainees, and for many years in solitary confinement.

According to the US’s own allegations, Rahim was, at most, a translator and facilitator for al-Qaeda. The US rationale, whether on intelligence or security grounds, for bringing him to Guantanamo and then detaining him for so many years is not obvious. However, once a person ended up in Guantanamo, getting released proved to be difficult. This was especially the case after Republicans gained a majority in the House of Representatives during the first Obama presidency and began blocking transfers (which they had not objected to when Obama’s predecessor, the Republican, George Bush, was president).

To leave Guantanamo, a detainee must first convince the Periodic Review Board that he is no longer a threat to the US and it is safe to transfer him to another country. The Board assumes the government’s accusations against a detainee are true and he must prove them false or – a more successful tactic – that he has turned a corner, is remorseful and no longer poses a threat. All this must be accomplished without access to normal legal mechanisms – including access to evidence or witnesses.

Rahim’s prospects from his 15 August Periodic Review Board hearing

Rahim, who has had three previous full reviews – in 2016, 2019 and 2022 – said at his last hearing that the Board had never given him the opportunity to have a lawyer present (transcript here; documents for this and other hearings for Rahim and the other detainees can be read on this webpage). Rahim does now have a lawyer at Guantanamo[8] to represent him on August 15, which raises his chances of being cleared for transfer considerably. This was certainly the case of the penultimate Afghan held in Guantanamo, Asadullah Harun Gul who finally secured his release last year (AAN reporting here).[9]

In her report, Special Rapporteur Ní Aoláin stresses that the right to legal counsel is well settled under international human rights law and international humanitarian law and is “vital to ensuring that the rights of all persons deprived of their liberty are respected.” It serves as a fundamental safeguard against torture and ill-treatment, arbitrary detention, and other breaches of fundamental freedoms and human rights and an entitlement on the part of all detained persons that attaches from the moment a person is detained. For Rahim, that right is finally being honoured 15 years into his detention.

What is also clear, however, from the transcript of Rahim’s last full review by the Periodic Review Board in April 2022 that not having a lawyer was not his only problem. The Board had employed an Arabic translator for Rahim. Even though he is an Arabic speaker and has at least some grasp of English, one would expect the Board to have provided a translator in his native language, which is Pashto. His responses do read as garbled and at times nonsensical: this may have been a language/translation issue. It is not clear, but that may be why the Board concluded he had shown “unwillingness to discuss pre-detention activities and beliefs,” and this prevented it from “assessing whether he has had any change in mindset or level of threat.” Even given that the set-up of the Periodic Review Board is fundamentally unjust and arbitrary, Rahim appears to have been treated particularly unfairly – expected to argue his case without legal advice and denied the opportunity to express himself or understand the Board’s questions properly.

The result was that the Board fell back on its default position of keeping him detained. It claimed he posed a “continuing significant threat to the security of the United States” and that it considered he was “a trusted member of Al Qaeda who worked directly for senior members of Al Qaeda, including Usama bin Laden.” Moreover, it asserted this “extensive extremist connection… provide[s] a path to re-engagement.”

It is unclear where it thought Rahim could “re-engage,” given the US no longer has a military presence in Afghanistan.

The Periodic Review Board under Biden

As well as now having a lawyer, the general environment for getting a decision from the Board to transfer is also more favourable since the advent of the Biden presidency. While Donald Trump was in power, although he never explicitly ruled out anyone leaving Guantanamo, the political drive to reduce numbers seen in the last year of Obama’s term ended abruptly. During his presidency, the Periodic Review Board judged just one person safe to be transferred, a Saudi Arabian citizen, Ahmed al-Darbi, who was repatriated and incarcerated in his homeland on 1 May 2018 (media reporting here). Since Biden came to power on 20 January 2021, 13 detainees, many of them held since the earliest years of the detention camp, have been cleared for transfer.

Rahim has already had one hearing during the Biden era when the Board decided against his release. However, this was also the case for some of the 13 men who it has subsequently cleared for transfer, so is not necessarily an indicator of what might happen this time. More problematic is that label, ‘high-value’: Rahim has always contended that the US has continued to detain him not because of anything he did, but because of what was done to him, that is, the CIA torture.[10] This accusation was echoed by Special Rapporteur Ní Aoláin, saying she was concerned that

[C]ontinued internment of certain detainees follows from the unwillingness of the authorities to face the consequences of the torture and other ill-treatment to which the detainees were subjected and not from any ongoing threat they are believed to pose.

She stresses that neither international humanitarian law nor international human rights law “countenances concealing evidence of prior misconduct by the detaining authority as a reason for continued detention.”

However, in one hopeful sign, the Board recently cleared one other high-value detainee for transfer, Guled Hassan Duran, a Somali national whom the US had incarcerated since 2006. Even more significant is the fact that the first ‘high-value’ detainee was actually released from the detention camp earlier this year. Majid Khan, a Pakistani national, who was born in Saudi Arabia, was transferred to Belize in February 2023 (see media reporting here).

If cleared for transfer, however, the fates of the 16 men before Rahim, all cleared and still detained, would then loom large. Being labelled as safe to transfer out of the detention camp is only the first hurdle: finding a country willing to take a detainee that he feels safe to go to and that the US believes will keep him secure and not torture him is the next.

The other route to freedom – habeas corpus

Rahim is pursuing a writ for his habeas petition in the US courts and is currently waiting for the court to rule on his Motion for Order of Immediate Release, filed 18 months ago, on 24 November 2021 (digital copy with AAN), an example of how petitions, in the Special Rapporteur’s words, “languish… in judicial pipelines.”

Rahim’s argument is that, in Biden’s words from 31 August 2021, “the United States [has] ended 20 years of war in Afghanistan — the longest war in American history” and therefore, as a prisoner of war, he should be released. The motion argues that “[t]here is no longer a battlefield for Rahim to return to.” The motion cites other statements from Biden, including this from 21 April 2021:

War in Afghanistan was never meant to be a multigenerational undertaking. We were attacked. We went to war with clear goals. We achieved those objectives. Bin Laden is dead, and al Qaeda is degraded in Iraq — in Afghanistan. And it’s time to end the forever war [emphases in original].

Hopes were raised for Rahim when the penultimate Afghan held in Guantanamo, Harun Gul, successfully petitioned for habeas corpus in 2021: it was the first successful petition in ten years. However, the court accepted Harun Gul’s petition because he was a member of Hezb-e Islami, which had signed a peace deal with the Ghani government. It ruled against his second argument that he should be released because the war in Afghanistan was over.

Instead, the judge accepted the US government’s position that, even though Biden had said the war was over, it was not. It accepted that the US’ authority to detain was not limited to the ground war in Afghanistan and that hostilities with al-Qaeda and its associated forces continued in Afghanistan and elsewhere. The judge said the court had to “afford the utmost deference to the Executive’s position on that question.” This was especially so, he said, in the absence of any declaration by Congress terminating the war.

The Kafkaesque contortions involved for the judge in accepting that a war could have been ended and still continue is, unfortunately, par for the course. Judges dealing with habeas petitions from Guantanamo detainees have proved supine in the face of an executive arguing its case on national security grounds.[11]

Indeed, the US Department of Justice has always fought habeas petitions tooth and nail. This has been the case whether the president was Republican or Democrat, and even while Obama and Biden had a declared policy of wanting to shut the camp down. The Department of Justice has argued for using secret evidence as well as ‘testimony’ and ‘confessions’ obtained from torture victims, has presented contradictory, discredited and worthless evidence and used procedural issues to delay the legal process for years. For administrations wanting to close the camp, the obvious way to bypass Congressional blocks on releasing detainees would be to reign in this fight by the Department of Justice against habeas cases.[12] Yet this is not a path that either Obama or Biden chose to take. Looking into the reasons for this, in her second special report on the Afghan experience in Guantanamo, the author concluded that not opposing habeas writs would mean recognising that detaining individuals outside a system of law is wrong.

Another anomaly

The strangeness of the Department of Justice and the Periodic Review Board both wanting to keep detaining this one last Afghan despite America’s war in Afghanistan being long over is not the only perplexing aspect of the US stance. They deem Rahim a threat because of his supposed al-Qaeda connections. Yet, as Trump and then Biden pushed to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan, they showed virtually no concern about the actual threat from al-Qaeda in Afghanistan.

In talks with the Taleban, both administrations dealt with Taleban who had long and enduring relationships with al-Qaeda – more than a dozen of the movement’s senior officials and commanders, now government ministers, were under United Nations sanctions because of their alleged links to terrorist groups. They include acting minister of interior Sirajuddin Haqqani, who also has a ten million dollar FBI reward on his head which says he “maintains close ties to the Taliban [sic] and al Qaeda … and is a specially designated global terrorist.”

Trump was content to get only the slightest of concessions from the Taleban on al-Qaeda and other foreign internationalist jihadi groups in Afghanistan as part of his February 2020 deal to withdraw US troops (see AAN reporting here). Also, that deal involved Trump agreeing that the Afghan government would release thousands of Taleban prisoners and then his officials pressurising an unwilling President Ashraf Ghani to do so. Yet, during all this time, the supposed risk from Rahim, one prisoner, detained for 16 years away from his homeland, tortured and abused, has apparently been viewed as a greater threat.[13]

Conclusion

Ní Aoláin writes that she “accepts and affirms the positive engagement [from the Biden administration] that enabled her visit.” She recognises that Biden is dealing with a situation he inherited and acknowledges that “[f]ew countries take meaningful steps to address egregious past human rights violations or undertake action to undo the most shocking of harms.”

In response to her very hard-hitting report, the Biden Administration has stressed its welcome of her visit and its openness to scrutiny. It noted that it had:

[M]ade significant progress towards responsibly reducing the detainee population and closing the Guantanamo facility. Ten individuals have been transferred out of Guantanamo since the start of the Biden-Harris Administration – one-quarter of the population we inherited – and we are actively working to find suitable locations for those remaining detainees eligible for transfer.

The far greater number of detainees cleared for transfer by the Periodic Review Board since Biden took office does show his willingness to at least minimise the ‘Guantanamo problem’. Yet the White House also said: “For those few [detainees] not yet eligible for transfer, we conduct periodic reviews to determine whether continued detention under the law of war is warranted.”[14]

The Biden administration continues to assert its right to detain men like Rahim without trial and indefinitely, and under what are actually highly questionable legal grounds.[15] In the case of the last Afghan held in Guantanamo, the US has wanted to keep detaining Rahim even after it pulled all its troops from his homeland and ended its war there. He now awaits his hearing on 15 August, to see if the Board will prove any more favourable to clearing him for transfer than in the past.

Edited by Rachel Reid

References

| ↑1 | See pages 167-169 of Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, ‘Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program’, 12 December 2014. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Fionnuala Ní Aoláin’s 23-page report, ‘Technical Visit to the United States and Guantánamo Detention Facility by the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism’ (14 June 2023) is in three parts. The first deals with the victims of the 9/11 attack, part of what Ní Aoláin says is mandated by her “abiding commitment to a human rights-based approach to victims of terrorism as victims of international human rights law and international humanitarian law.” The second deals with the Guantanamo detention facility and the third with resettlement of detainees and reparations. |

| ↑3 | At least 15 of the detainees were under-18s. They included two 14-year-old Afghans, Asadullah and Naqibullah, who had been kept and raped by a US-allied, anti-Taleban commander, who created so much mayhem and criminality that the US eventually detained him in Bagram. It sent the two abused boys to Guantanamo, eventually releasing them, with this justification:

Though the detainee may still have some remaining intelligence, it’s been assessed that that information does not outweigh the necessity to remove the juvenile from this current environment and afford him the opportunity to “grow out” of the radical extremism he has been subject to. See also ‘Guantánamo’s Children: The Wikileaked Testimonies’, Center for the Study of Human Rights in the Americas, University of California, Davis, 22 March 22, 2013. See also the New York Times’s “The Guantánamo Docket,” in particular Asad Ullah, ISN 912, Assessment, 2003, and Naqib Ullah, ISN 913, Assessment. |

| ↑4 | For more on the lack of accountability, see the author’s 2017 report into the civil case against the two psychologists who designed and oversaw the implementation of the CIA torture programme, which detailed cases. |

| ↑5 | For Obama’s comments, see Press Conference by the President, 1 August 2014, here. Reading this transcript in retrospect, what is interesting is that a journalist was able to ask a follow-up question, but chose not to. |

| ↑6 | The Senate report said:

The summary documents of the CIA’s interrogation emphasized that the primary factors that contributed to Rahim’s unresponsiveness were the interrogation team’s lack of knowledge of Rahim, the decision to use the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques immediately after the short “neutral probe” and subsequent isolation period,… the team’s inability to confront Rahim with incriminating evidence, and the use of multiple improvised interrogation approaches despite the lack of any indication that these approaches might be effective. The summary documents recommended that future CIA interrogations should incorporate rapport-building techniques, social interaction, loss of predictability, and deception to a greater extent. (p167) |

| ↑7 | Other detainees may have been held by the CIA briefly, but not for long periods of time at black sites before arriving in Guantanamo. |

| ↑8 | Rahim has had lawyers working pro bono on his petitions for habeas corpus, but none previously at Guantanamo. His former lawyer Carlos Warner wrote a castigating description of trying to represent a high-value detainee. He was legally gagged from speaking about most aspects of his case (which would reveal classified information) or even why he considered his client innocent. He said the government could say whatever they liked about Rahim, but he could not even discuss the government’s allegations with his client, let alone tell the outside world why he thought he was innocent. He says to his readers:

Imagine trying to get to the bottom of a bar fight that resulted in a death. I can’t tell my client who was killed or why the Government says he’s involved. I can’t even tell him when the assault occurred or in what bar the assault took place. I certainly cannot interview or cross-examine his accusers. Moreover, I can’t visit the bar or talk to any other witness to the fight. I am also prohibited from speaking with the coroner or any of the investigating officers. Sometimes, the Government will say “we have important evidence about your client regarding our allegation, but we can’t tell you what that evidence is.” Sometimes, the Government just tells the judge without telling or notifying me at all. All of my communications with my client are observed and recorded. All of my legal correspondence is read and inspected by the Government. Guantanamo has been referred to as “Kafka-esque,” and that reference is right. “Catch-22” also aptly describes the legal malaise that is currently called Guantanamo habeas corpus. Nothing in my legal training prepared me for this endeavor. (‘Navigating a “Legal Black Hole”: The View from Guantanamo Bay’, Akron Law Review, 2014 (pp31-51). |

| ↑9 | Harun Gul finally got a lawyer just a few days before a Periodic Review Board hearing in 2016 and a relatively favourable assessment: the Board hinted that if he had had representation earlier, it might have deemed him safe to release. However, he was only cleared for transfer after Trump left office, at his first hearing during the Biden presidency, on 8 October 2021. That same month, on 21 October, Harun Gul also successfully argued that he should be released through a petition for habeas corpus: it was the first successful petition by a Guantanamo detainee in ten years (AAN reporting here). |

| ↑10 | “How come they make me admit to things in order to get out?” Rahim wrote to his habeas lawyer on 27 April 2016. “I am an innocent man. Parole comes after a trial, not before. They are holding me because I was tortured. Please give me a fair hearing, with my lawyer.” See the author’s 2021 report, ‘Kafka in Cuba, a Follow-Up Report: Afghans Still in Detention Limbo as Biden Decides What to do with Guantanamo’, p51. |

| ↑11 | “Careful judicial fact-finding [in habeas cases],” one 2012 study by the Seton Hall University School of Law found, has been “replaced by judicial deference to the government’s allegations,” with the “government winning every petition.” Following the denial of seven habeas appeals in 2010, The New York Times on 13 June 2012 described the development of “substantive, procedural and evidentiary rules” as “unjustly one-sided in favor of the government.” It said the rejected appeals had made it “devastatingly clear” that the current court system in the US “has no interest in ensuring meaningful habeas review for foreign prisoners.” For more detail on the habeas petitions of some of the last eight Afghans held in Guantanamo, see the author’s special report for AAN, ‘Kafka in Cuba: The Afghan Experience in Guantanamo’, November 2016. |

| ↑12 |

This was proposed in a piece for Just Security by Hina Shamsi (Director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project), Rita Siemion (Director, National Security Advocacy at Human Rights First), Scott Roehm (Washington Director, Center for Victims of Torture), Wells Dixon (Senior Staff Attorney, Center for Constitutional Rights), Ron Stief (Executive Director, National Religious Campaign Against Torture), Colleen Kelly (co-founder, September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows), ‘Toward a New Approach to National and Human Security: Close Guantanamo and End Indefinite Detention’, 11 September 2020: [T]he executive branch can expedite transfers by not opposing detainees’ habeas cases. There is no requirement in law or in practice that the government contest detainees’ habeas petitions. [T]he foreign transfer certification requirements don’t apply when a detainee’s release or transfer is pursuant to the order of a U.S. court or competent tribunal that has jurisdiction over the case. |

| ↑13 | The author’s 2021 report, ‘Kafka in Cuba, a Follow-Up Report: Afghans Still in Detention Limbo as Biden Decides What to do with Guantanamo’ looked at why the last eight Afghan detainees had spent so long in Guantanamo:

A fundamental obstacle for these men is that they have been castigated as the ‘worst of the worst’. The phrase, used by US Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld in early 2002 and repeated endlessly, created monsters in the public imagination of all the detention camp’s inmates. When Obama took office, and Guantanamo became a political football, the gap between the actual and the perceived – or portrayed – threat posed by the detainees widened yet further; Republican members of Congress who had been unconcerned about transfers suddenly strived to block them after Obama took office. In the absence of any proper scrutiny of allegations and evidence, there has been nothing to reduce these imagined monsters down to size or create a space to deal with them rationally. After scrutinising the files of all eight Afghans featured in this report in-depth, nothing suggested they were especially dangerous individuals. Yet, this is how the US state has treated each one, by default, and without regard for facts or evidence. |

| ↑14 | The statement went on to say: “Separately, the military commissions process continues for those detainees subject to criminal prosecution.” |

| ↑15 | That assertion that detainees are being held under the law of war is strongly contested, especially given that President Bush decided to house the detainees in Guantanamo so that they would not enjoy rights that might accrue from them being on the US mainland. Obama’s first Special Envoy for Guantanamo Closure, Dan Fried, for example said that: “Guantanamo was neither grounded in the laws of war nor in criminal justice.” His contention was that, “once you have established a system outside of either international or US law, which this was, then it’s very hard to reintegrate it back into a legal framework. (Quote from page 5, Kafka in Cuba, a Follow-Up Report: Afghans Still in Detention Limbo as Biden Decides What to do with Guantanamo). For more on the legal discussion and background, see Chapter 3: Sources of Information and the Shifting Legal Landscape (p16-21) in Kafka in Cuba: The Afghan Experience in Guantanamo. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign