United States Institute of Peace

When it comes to child malnutrition, specialised terminology is unavoidable. We have put together a glossary explaining the terms in the infographics in this report. Briefly, some of the acronyms used in the literature and in this report are: Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM), which is made up of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) and Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM).

Afghanistan has long struggled with poverty and food insecurity, problems compounded by poor transport infrastructure and conflict which has hampered and fractured trade and aid logistics. These characteristics have historically made the remoter provinces of the country more prone to malnutrition. Yet all areas have suffered from the collapse of the Afghan economy following the Taleban takeover in August 2021. As documented in the three-instalment AAN series “Living in a Collapsed Economy” between 2021 and 2022 (see here, here and here), the livelihoods of nearly all classes of people have worsened. Three consecutive years of drought have only exacerbated food insecurity for many (see AAN reporting here and here).

According to the World Food Programme (WFP), Afghanistan is currently at its highest risk of famine in a quarter of a century, with nearly 20 million people – more than half of its population acutely food-insecure, including more than 6.1 million people who are on the brink of famine-like conditions. The situation has reached unprecedented emergency levels, and as always, it is taking a high toll, especially on children, with some 3.2 million under 5s and 840,000 pregnant and lactating women are suffering from severe or moderate acute malnutrition, according to the revised 2023 humanitarian response plan.

According to UNICEF, Afghanistan has one of the world’s highest mortality rates among under-fives. The World Health Organisation estimates that every day in Afghanistan, some 167 infants die of preventable diseases, while Save the Children has reported a 47 per cent increase in the number of malnourished children treated at its mobile health clinics from January to September 2022 (from 2,500 to 4,270). While food insecurity is the major driver in child and maternal mortality, lack of access to proper healthcare and medicine also makes illnesses such as pneumonia and measles so deadly in Afghanistan.

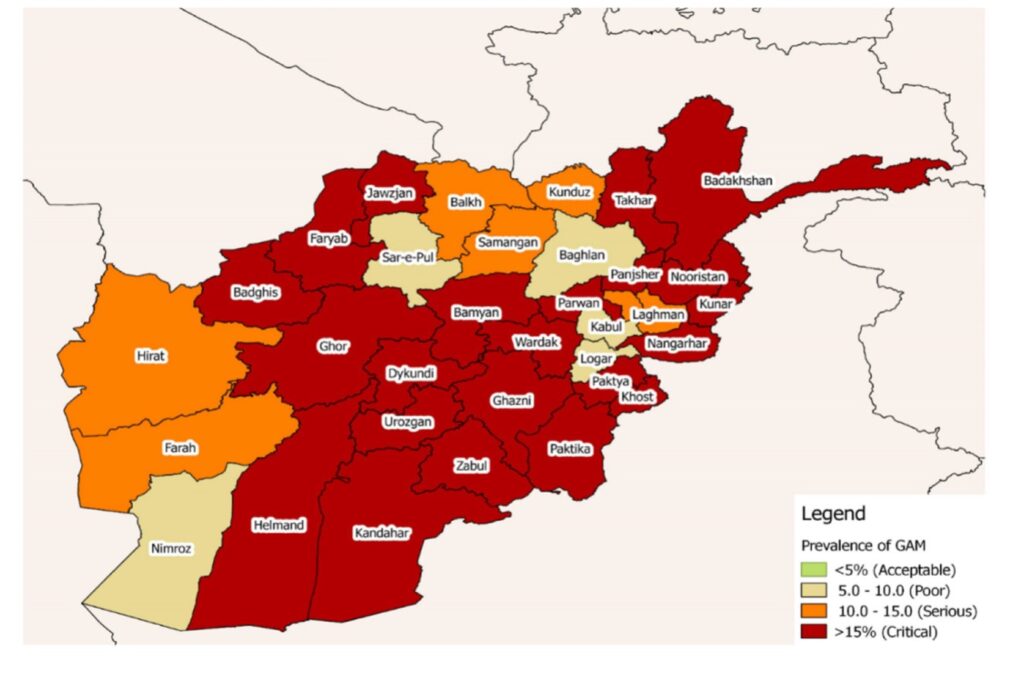

The most recent forecast from the Integrated Food Security Phases Classification (IPC) [1], the global standard for assessing food insecurity, “Afghanistan: Acute Malnutrition Situation for September October 2022 and Projection for April 2023”, was published in October 2022. It forecasted that in April 2023, 875,224 Afghan children would be suffering from Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) and 2,347,802 from Moderately Acute Malnutrition (MAM), while 804,365 pregnant and lactating women would also have acute malnutrition. The maps below show the situation in autumn 2022 and the progress of malnutrition across the country throughout winter-spring 2023.

The nearing harvest will temporarily reduce food insecurity (as shown by the projected food insecurity estimates by the IPC) and somewhat ease malnutrition across the country. However, to make it through spring 2023, many families were forced to take dramatic steps, jeopardising their household economy and undermining their ability to get through the coming ‘hungry seasons’ of winter and spring. These steps were described in the Afghanistan Socio-Economic Outlook 2023 published by UNDP in April:

[M]ore than 4.3 million households have borrowed simply for securing food. Many households have mortgaged their future, having sold productive assets such as their last female animals (1.1 million) or other income-generating equipment or means of transport (over 0.6 million), and even their houses or land (over 0.3 million). In many cases, households were forced to mortgage their children’s future by seeking recourse to child labor (more than 850,000) or marrying their daughters earlier than intended (nearly 80,000), to combat extreme food insecurity. (pp 63 – 64)

Map 1: Acute Malnutrition in September – October 2022

Map 2: Projected Acute Malnutrition for November 2022 – April 2023

This report aims to navigate the data about child malnutrition and provide an overview of the situation in Afghanistan, how malnutrition is influenced by economic, geographic and even cultural factors, how it has worsened through the past decade and how it is experienced today by those affected by it. To this end, AAN has interviewed three healthcare workers, who work directly with malnutrition children, each from the provinces of Daikundi, Helmand and Takhar, as well as eight parents from Daikundi (one), Helmand (two), Kabul (two) and Takhar (three) whose children are suffering from malnutrition.[2]

The geography of hunger

Conflict, poverty, drought, food insecurity, limited or no access to health services, poor water quality and sanitation, insufficient maternal nutrition and low immunisation rates for children resulting in a high disease burden have all contributed to the high child malnutrition rates in Afghanistan. Malnutrition is widespread across the country, but its prevalence is greater in some areas and some sections of the population. In this section, we map the geography of hunger in Afghanistan based on both spatial and human characteristics. The next section will look at how and why it has varied over time.

Rural areas tend to be more vulnerable to malnutrition because of their greater poverty rates, difficult logistics and lower awareness of the symptoms of malnutrition, but even more significantly, the lack of nearby medical facilities and availability of suitable treatments. As a subset of rural areas, remote and/or mountainous places tend to be even more greatly affected – and at the same time, the increased distance and costs associated with accessing healthcare mean fewer malnutrition cases are reported compared to the actual number.

Thus, isolated provinces such as Ghor, as well as rural areas in Takhar and Badakhshan provinces in the northeast, all comparatively poor and highly dependent on local crops, have suffered heavily from the recent years of drought and crop failure. According to a nurse from Rustaq district of Takhar, whose work has focused on malnutrition for some years, large single-income households are typically worst hit by the problem:

Children who are malnourished are more likely to come from low-income families, with only one person serving as the primary earner and supporting a large extended family. Families in Takhar are extremely impoverished, earning just 180-200 Afghans [a day]. But the households are very large: as many as 15 people need to be provided for by only one person, which leads to insufficient and uneven access to food for all the family members.

In Helmand, malnutrition is present in all districts, but affects particular areas more severely. As one NGO healthcare worker from Lashkargah remarked, the hilly northern districts, such as Musa Qala and Nawzad, or the southernmost, the desert districts of Khaneshin and Dishu, register more malnutrition cases. When interviewed by AAN, the health worker explained that:

The reason for the high cases of malnutrition [in those districts] is the economic status of families who are farmers and livestock breeders and have been affected highly by the drought.

However, the impact of malnutrition is also felt inside the towns and cities because of the loss of income faced by many urban residents after the withdrawal of the international military and an influx of internally displaced persons from rural areas; they have been forced to settle in precarious living conditions without access to safe water and sanitation.

When families become food insecure, it is specific age and gender groups that are affected the most. Children under the age of five are considered most at risk of malnutrition and related illnesses, which is why this age group is usually featured in relevant statistics. Pregnant and lactating mothers are a second vulnerable group.

International organisations working in healthcare in Afghanistan have reported an increasing trend of more newborns and infants being admitted as inpatients to their nutrition centres than in the past. According to a recent report by the international NGO, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF),[3] the percentage of infants under six months of age admitted to their paediatric intensive nutrition centre in Herat has been reported “most concerningly” on the increase and reached 61.5 per cent of all patients in February 2023, while in MSF’s Kabul centre, the percentage of infants under one year old reached 67 per cent. According to the same MSF briefing note:

Breastfeeding in Afghanistan is challenged by the practice of child marriage, negative cultural beliefs related to breastfeeding, lack of family planning, poor access to clean drinking water, and limited access to information on optimal breastfeeding practices. (p 8)

These factors affect the above-mentioned age groups and are made worse by the absence or the prohibitive costs of safe replacement feeding, such as formula.

The healthcare worker from Lashkargah highlighted another pattern, that malnutrition takes a heavier toll on girls than boys, because in times of crisis, boys are more likely to be better-fed and taken care of – to the detriment of their sisters.

Girls are at risk in the family because of the culture and literacy levels. Boys are paid attention to and taken care of. I see it all the time that when boys are sick, their mothers bring them [to the hospital], but when girls are sick, [only] their grandmothers bring them to the clinic or hospital. When I ask why, they say boys are important and their mothers should take care of them. When there is little food, parents mostly try to feed their sons, rather than their daughters.

This trend is confirmed in reports from international organisations: for example, MSF reported that in 2022, girls faced a 90 per cent higher mortality rate compared to boys in their inpatient therapeutic nutrition centre in Kandahar, pointing to families’ deprioritising their daughters both in terms of providing food for them and seeking out medical care.

Such discrimination affects mothers as well. They are also deprioritised (or put others first) when it comes to food in the family, are then malnourished during pregnancy, often suffer anaemia after giving birth and have problems breastfeeding their babies, who in turn become victims of malnutrition. Other cultural traits, such as the frequent lack of family planning, only add to the problem, as one healthcare worker from Daikundi province described:

[I]lliterate families who don’t have any primary health education and only follow old traditions are also at risk of having malnourished children. They don’t have family planning, so they don’t consider intervals between births. Therefore, they give birth to children who are weak and then become malnourished. In addition, children who are born premature and children who are born on time but with low birthweights – because their mothers were malnourished during their pregnancy – are at risk of malnutrition.

Finally, some diseases with varying local or regional severity patterns, such as Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD) and Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI), often appear together with malnutrition, each contributing to the other’s morbidity. This is especially true in winter when food security deteriorates in many households. Malnutrition has, for example, been considered by some studies as a contributing factor – together with COVID-19 – to the deadly measles outbreak that hit many provinces of Afghanistan in 2022.

A chronology of hunger

While malnutrition has always affected some places more than others in Afghanistan, and girls more than boys, overall, it has been worsening over the last decade, and dramatically so after the Taleban takeover, which precipitated the collapse of Afghanistan’s economy.

In 2004, the National Nutrition Survey (NNS), which is conducted in Afghanistan every decade, found that 60.5 per cent of children under-five were suffering from stunting [4], while 8.7 per cent were suffering from wasting [5]. A decade later, the 2013 National Nutrition Survey showed a marked reduction in the number of stunted children under 5, down to 40.5 per cent, but the number of wasted under 5s had risen to 9.5 per cent. There was also an improvement in the number of underweight children from 33.7 per cent in 2004 to 24.6 per cent in 2013. The 2013 survey did, however, raise the alarm on the severity of child malnutrition, revealing eight provinces where general acute malnutrition levels were higher than the WHO threshold of 15%, marking a ‘Critical’ situation – Urozgan (21.6%), Nangarhar (21.2%), Nuristan (19.4%), Khost (18.2%), Paktia (16.7%), Wardak (16.6%), Kunar (16.2%) and Laghman (16%). In the decade that followed, the situation for children continued to deteriorate. After 2014, child malnutrition rates started to worsen (as the graph below shows).

Graph by AAN.

A key event affecting the incomes of many Afghans was the withdrawal of NATO troops from most areas of the country, as they handed over responsibility for security to the Afghan National Security Forces (further reading in this AAN Thematic Dossier). The transfer was completed by the end of 2014. It brought with it not only a deterioration of security but also a decline in the national income because the foreign armies had spent money and given aid. That income had been spread quite widely and often went to remote areas where the insurgency was strong. As bases and outposts closed locally, the loss of jobs and other sources of income was often substantial. Up to 2014, the standard of living had generally been rising in Afghanistan, but the NATO withdrawal marked the first of several economic shocks from 2015 to 2023 that had detrimental knock-on effects on the ability of many Afghan families to provide adequate nutrition to their children. The figures below tell this story.

In 2015, an estimated 1.2 million children under 5 (39% of this age group, based on WHO population estimates) suffered from general acute malnutrition (500,000 severely and 700,000 moderately) and some 250,000 pregnant and lactating women. That year, the Strategic Response Plan, published by OCHA and focused on addressing the most acute life-saving needs, aimed at assisting far fewer than that number – just under half a million under-fives (155,279 suffering severely and 210,265 moderately from acute malnutrition and 134,071 pregnant or lactating women) because, it said, the aid effort that year was “[c]onstricted by partner capacities, accessibility, and resource availability.”

By 2016, the number of malnourished under-fives had increased to some 2.9 million (some 58 per cent of the total), according to the 2016 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), which is the annual appeal for humanitarian aid. Nearly 1 million children were slated for assistance because they were acutely malnourished (365,000 severely and 632,000 moderately), twice as many as the previous year.

Malnutrition remained a heavy burden for the Afghan people in 2017, with 1.3 million under-fives in need of treatment for acute malnutrition, and with levels of SAM breaching emergency thresholds in 20 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, according to the 2017 Humanitarian Needs Overview (see also the 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan).

The prevalence of malnutrition continued to increase as the intensifying conflict endangered people’s livelihoods and made access to many areas more difficult for health organisations and other humanitarian actors. In 2018, acute malnutrition affected 2 million children under 5, with “a staggering 600,000 children (29 per cent) suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM)”, along with almost half a million pregnant or lactating women. 75 per cent of the affected children lived in 22 provinces, designated as ‘priority’ (see the 2018 Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster Annual Report).

2018 Malnutrition Severity Map, showing the prevalence of General Acute Malnutrition (GAM)

In 2019, the Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster Annual Report revealed two million acute malnutrition cases, including 600,000 suffering severely.

In 2020, the numbers again swelled, with acute malnutrition affecting 2.9 million children, 784,000 of them suffering severely (see the 2020 Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster Annual Report). There were also 650,438 malnourished pregnant and lactating women in need of supplementary nutrition. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic that year had devastating consequences, pushing an additional 106,214 children into severe and 284,688 into moderate acute malnutrition and leaving 87,298 pregnant and lactating women in need of life-saving interventions. The number of provinces classified at emergency levels rose from 22 to 26 (for the economic effects of Covid-19, read this AAN report)

As the Taleban sued for control of the country in 2021, fighting intensified, making trade, travel, sowing and harvesting difficult for many. Malnutrition worsened, with an estimated 3.13 million children under 5 at risk of acute malnutrition, (895,000 severely and 2.2 million moderately) as well as 700,000 pregnant and lactating women (see this November 2021 Health Cluster Bulletin and the 2021 HRP).

The fall of the Republic in August 2021 and the ensuing economic collapse had pushed an unprecedented number of Afghan households into poverty by 2022. In that year, an estimated 3.88 million under-fives, with more than half facing acute malnutrition (1.08 million severely and 2.8 million moderately)[6], as well as 836,657 pregnant and lactating women. One million under-fives were believed to be at risk of death. (Figures from the 2022 HNO and HRP).

Child malnutrition in 2023: the view from the field

The Afghanistan Humanitarian Response Plan for 2023 estimated that acute malnutrition will affect over four million vulnerable individuals this year, including more than 840,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women and 2,300,000 children suffering moderately and 875,000 severely.

Interviews carried out by AAN with both health workers and the parents of children who have suffered or still suffer from acute malnutrition give an idea of how the situation is deteriorating due to the economic crisis and the shortages of medical care. Primary healthcare centres are often working under strained conditions, with reduced staff, equipment and stocks of medicines.

The country’s health system received a double shock in August 2021, both a brain drain of qualified staff, as reported by the media, and a reduction in international funding (see reporting by the Development News website, Devex), with primary and community healthcare suffering the most. The Taleban ban on women working, first to NGO workers in December 2022 and later to UN staff in April 2023, has further reduced humanitarian capacities to deliver programmes to fight malnutrition and poverty. Even though female healthcare workers are largely exempt from the ban, according to the Revised Humanitarian Response Planreleased by OCHA in June 2023, conditions on employing female healthcare workers, such as the necessity for them to be accompanied by a mahram (a close male relative), have resulted in, “additional costs and budgeting, shrinking donor funding, and potential challenges in meeting the minimum operational standards due to the limited capacity of implementing partners.” (pp. 38-39)

A glimpse at the increased difficulties encountered in helping malnourished children and their mothers can be gathered from these figures given by the Revised Humanitarian Response Plan:

[D]uring the first four months of 2023, approximately 14.7 million people received at least one round of food and livelihood support, compared to 19.1 million in 2022. Health care was provided to 5.4 million people, an increase from 4.7 million in 2022. Support to prevent and address acute malnutrition reached 2.4 million children and nursing mothers, down from 3 million in 2022. (p 11)

A veteran nurse from Takhar, interviewed in March, summarised standard procedures to treat malnutrition in place at her clinic, before detailing how they were now being forced to let patients down.

If the MUAC [measurement of the mid-upper arm circumference – a key indicator] is less than 11.4 cm, we usually treat [the child] in the clinic and they are hospitalised. If it’s between 11.5 and 12.5, we treat them by providing enough supplements and resources.… RUTF [ready-to-use therapeutic food] and RUSF [ready-to-use-supplemental food] are resources provided for malnourished children…. Children that weigh less than 3 kg, are shorter in height and have a poor appetite are usually hospitalised and given medication and milk. When they show improvements, or their weight increases to 4kg, we discharge them and give them the necessary resources.

Such standards, she said, have become difficult to adhere to since December 2022 because of faltering stocks of therapeutic food and the pressure on health centres brought about by the sheer number and desperation of ailing families:

For the past almost four months, we’ve have had very few resources left. The cases of severe and moderate malnutrition have increased significantly in this time. Because of fewer resources, we had to start providing patients with the foods available in our clinic…. Resources were not being cut before. I do not know if we are not getting any supplies because of the current government. We have been without resources for four months now. I believe the Agha Khan Foundation or the World Food Programme were providing for us, but this support has stopped…. Our clinic is very small. The rooms are cramped, we’re short on staff and we have a heavy workload.

Speaking to the interviewee again in June, she did say international support had now resumed, with resources being provided by UNICEF and the World Food Programme. However, her experience was not singular. Other clinics and healthcare centres are being put under pressure by a growing caseload and, often, fewer resources. According to a healthcare worker in Daikundi, in the past, the provincial hospital would not host more than 15 malnourished children at any given time, but in March 2023, the malnourishment ward was hospitalising 25 to 30 children every day.

Understaffed and overcrowded clinics mean severely malnourished patients get discharged as soon as they become even moderate acute malnourished levels. Ideally, they are provided with food supplements and all the necessary information and guidance to continue their treatment at home. However, this can result in improper handling of the therapy by families and cause recurring malnutrition in a child. The nurse from Takhar said:

Some children receive food from us, but we don’t see any improvement when they return. Most mothers have many children and distribute the food and resources we provide for the malnourished child to their other children. Some have even said their husbands or mothers-in-law eat the bars or biscuits we gave them for their malnourished children.

She added how, in winter, especially, it was not easy even to discharge patients:

When the children start to improve, we contact their families to come and get them, but they don’t show up. They choose not to pick up their wives and children because they are getting some food – beans and bread – and the clinic’s warm. [When they finally show up] their husbands tell us that they don’t have any food at home and it’s very cold there. Therefore, they should stay with us for some more days.

Family evaluation of the costs/benefit of referring their malnourished children for medical treatment can also get in the way of successful treatment, as is apparent from the nurse’s observations:

Some children receive only the first treatment, and their families don’t show up for the next appointment because of the cost of travelling long distances. They claim the cost of their journey is much higher than the food that we provide, so they don’t come back to finish the treatment.

In some instances, the opposite can also be true, she added:

Families keep coming back to us for support for their children, even when they aren’t classified as malnourished anymore, and when we can’t assist them, they become irate and shout that we’re lying and taking the aid for ourselves.

We heard several such accusations from health workers that families do not respect them – realistic reporting, especially for female staff. We also heard accusations about health workers from some of our interviews with parents, particularly that they keep the, by now, rare medicines from those most in need and put them instead on sale on the black market.

A mother from Takhar, her two-and-a-half son malnourished, claimed to have witnessed healthcare professionals taking some of the medical resources for themselves and their families. “They also sell products like ready-to-use therapeutic food in the form of biscuits and milk to the market,” she told AAN, adding that the abusive practice persisted notwithstanding inspection by a foreigner (whether a member of staff or monitor was not clear) and subsequent personnel changes or transfers in the hospital. She blamed the problem on the fact that most healthcare professionals had left after the collapse of the Republic and were replaced by new ones who were not satisfactory. She went up to say that the new doctors and nurses would provide good care only upon receiving gifts from patients and remarked – a Tajik herself – that they would be biased against Uzbek mothers, even uttering racist slurs against them.

Several parents also complained that their first visit to a clinic was the only time they received free nutrition treatment. Afterwards, they were told there were no resources to continue the treatment, as a forty-five-year-old mullah from Helmand recounted.

The first time we went [to the clinic], they gave us RUTF [ready-to-use therapeutic food] and some medicine. After that, every time we went, they said there was no RUTF and no medicine. Each time, they told me to visit the clinic next time because there might be RUTF and medicine, but there never was. I could buy the medicine in the bazaar but couldn’t find RUTF…. The medicine that comes for children is not given to anyone. They always make excuses and say nothing remains in the clinic. Now [my son] can eat bread little by little. He’s very weak, and when seasonal diseases come, he gets sick easily. He’s two years old but looks like he’s only one. He still can’t walk. He still crawls.

In the absence of therapeutic food, many families resort to the less expensive types of milk powder or, often, to even cheaper replacements such as sugar water. Another father from Helmand told AAN how all his four children suffered from malnutrition, but he was unable to provide them with nutritious food except, when possible, milk powder:

All my four children are malnourished. My eldest son is six years old, and he was very weak when he was born.… The village doctor told me I should take him to the clinic so they could give him nutritious food. I told him I couldn’t [because] the clinic is far from our home, and I didn’t have money to rent a car and take my son there. Then he told me to at least buy milk powder to help my son survive. Since he’s my first child and I love him, I borrowed some money from a neighbour and bought him milk powder.… The doctor also prescribed some vitamin syrup, but I couldn’t afford it. Then, when he grew a little bit, I soaked bread in water and gave it to him. He is still weak and thin.… My other children are malnourished too. My wife doesn’t have milk, so she can’t breastfeed. All my children grew up with milk powder. The first two can eat bread and other food now. But the other two are small and can only have milk powder. Sometimes I really can’t afford milk powder either. We boil water and add some sugar and give that to them instead of milk.

For him, the economic constraints leading to insufficient nutrition are at the roots of all the health problems of the family:

[Their] mother didn’t eat well during her pregnancy. Our [household] economy has not been good and she couldn’t eat well. I’m a farmer and have no other income. I get wheat, potato and beans from the farms. I work on another person’s land and the landlord only gives me one-quarter of the harvest…. Because of the drought, I can only keep a few sheep and those with a lot of difficulties. Everything’s expensive and there’s drought, so the harvest isn’t good. We can only have bread, potato and beans as our food. We can have meat maybe once in a few months.

The decline in household economies, coupled with a decline in available healthcare, is proving a lethal mix across the country. No longer limited to remote rural areas, malnutrition has crept into the very heart of Afghan cities. Here, a father from Kabul describes how poorly and weak his daughter has continued to be:

There wasn’t enough [food] at home when Mina was born. Her mother didn’t eat well either. Women need to eat well when they’re pregnant and breastfeeding, but my wife didn’t eat well because of our economic situation. She was anaemic and needed blood because she’d had an operation.… When Mina was born, she weighed one kilo and eight grammes, while a healthy newborn weighs three to four kilogrammes.[7]

I took [Mina] to a government hospital and they said she had mild malnutrition, so they didn’t give her nutrients. I took her to another hospital, and they gave her nutrients for one month. She is still weak and her hair doesn’t grow. If it grows, it soon falls out. When I take her to the doctor, they say she’ll be fine. But she doesn’t grow and I don’t know what to do. They don’t give her medicine or food when I take her to the clinic. They say that now she is fine and doesn’t need nutrients, or they make excuses and say they don’t have any nutrients. She’s three years old, but when you look at her, you think she’s less than a year. She doesn’t grow and she can’t walk. She’s very weak. Her bones can be seen under her skin. She can’t talk either. Now she’s almost three years old and she weighs only seven kilogrammes.

Mina’s story highlights the strong connection between mothers’ and children’s health. Pregnant women in Afghanistan are very much at risk of the same economic and medical shortages causing child malnutrition. Mothers are often the first to suffer when household economies weaken, as the nurse in Takhar recalled:

Just three days ago, we had a woman here who was eight months pregnant and in critical need of care: she was malnourished, which contributed to her anaemia, and desperately required a blood transfusion. The family lacked the money to locate and purchase blood, and because the transfusion wasn’t arranged on time, both the woman and the child died before her husband could secure transport from Takhar to Rustaq to donate blood. The woman’s husband was sobbing at her feet and asking how he would carry her [home]. The midwives gave him some cash by putting together 20, 30 or more afghanis, which they’d been given by patients as gifts. When he left, he said he could carry his wife home now, but who knows where he’d get the money for her shroud and funeral.

Conclusions

The economic and healthcare crisis, fuelled by the international withdrawal, the loss of capital and human resources and the discriminating policies by the Taleban that prevent women from studying, working and accessing healthcare, risk reversing one of the achievements of the past two decades in Afghanistan – the slow reduction in the country’s neonatal and child mortality rate (together with the maternal mortality rate, as pointed to in this recent article), previously among the highest globally and which risk returning so.

While the slow-burning, ever-intensifying humanitarian catastrophe befalling Afghanistan’s children is well-known to all international players, finding viable ways to prevent it seems elusive. The Taleban are unlikely ever to relent – or at least to take the first step in doing so – on their restrictive conditions for women working and other forms of gender-based segregation, while international donors are increasingly showing fatigue towards financing programmes in Afghanistan (see AAN report here).

Afghanistan has in the past been faring better, ie receiving more attention, than many other countries in crisis. However, that may be changing. The fact that donor commitments for the 2023 Humanitarian Response Plan have only been trickling in so far – only USD 632.2 million for an appeal of USD 4.6 billion as of this writing – leaves little room for optimism.

WFP announced in May 2023 that it would have to cut emergency assistance to four million people for the second month running due to severe funding constraints. Since the beginning of April 2023, eight million people have been left out of emergency food assistance due to persistent funding shortfalls. On 30 June, it had more bad news. “It’s five million people we are able to serve for another couple of months, WFP Country Director, Hsiao-Wei Lee, told Reuters: “But then beyond that we don’t have the resources. That I think conveys the urgency of where we stand.” She said the reductions would start in August, fall further in September and halt in October, according to the WFP’s estimates of current funds and financial assistance promised by donor countries in coming months.

Against the backdrop of this difficult scenario, the principal organisations focussed on delivering malnutrition support recommend against, among other things, financial cuts by donors and caution against the possibility of humanitarian actors disengaging from fieldwork due to the Emirate’s segregating policies. Instead, they advocate for prioritising feeding programmes for infants, young children and pregnant and lactating women to prevent dangerous forms of newborn malnutrition and trends of relapsing later. They also advocate for the timely treatment of moderate acute malnutrition to prevent these cases from becoming severe. They call for a redoubled focus on primary and secondary healthcare across the country to guarantee access to all portions of the population, improve the detection of pregnant and lactating women and child malnutrition and prevent cases from becoming too severe to be treated successfully.

The emergency assistance needed to fight malnutrition constitutes the most fundamental part of the humanitarian funding for Afghanistan, one that represents the future of Afghanistan embodied in the survival and the health of its next generation. To scrap it means to endanger the future for these children and for Afghanistan.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour and Kate Clark

References

| ↑1 | IPC assesses acute malnutrition utilising anthropometric data, ie data related to measurements and proportions of the human body, from the National Nutrition SMART Survey (NNS), as well as other data related to the determinants of malnutrition, including feeding practices, morbidity, sanitation and hygiene, and food security. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | All interviews were conducted by phone between February and March 2023. The provinces were selected because they have regularly displayed significant levels of child malnutrition and are representative of the situation in the central highlands, the south and the northeast, respectively. Interviews in Kabul offered insights on the situation in urban areas. |

| ↑3 | “MSF Briefing Note on Malnutrition and Health”, June 2023, pp 7, 8 (AAN has a copy). |

| ↑4 | WHO defines a stunted child as one who is too short for his or her age and is the result of chronic or recurrent malnutrition. Stunting is a contributing risk factor to child mortality and is also a marker of inequalities in human development. Stunted children fail to reach their physical and cognitive potential. |

| ↑5 | According to WHO, child wasting refers to a child who is too thin for his or her height and is the result of recent rapid weight loss or the failure to gain weight. A child who is moderately or severely wasted has an increased risk of death, but treatment is possible. |

| ↑6 | According to the 2022 National Statistics Yearbook the number of Afghan children under 5 years old stood at 6.17 million (see here). |

| ↑7 | The mentioned weight is very low indeed – typically babies require incubation if they are below 1.5 kilogrammes. The father made no mention of this having happened. It would seem a miracle if Mina survived without incubation at that weight. |

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign