“We need to breathe too”

It has been three weeks since the Taleban announced a new order, prescribing a strict dress code for women, that they should not leave the house without real need and if they do, should wear what is termed ‘sharia hijab’, with face covered entirely, or except for the eyes. The order made a woman’s ‘guardian’ – her father, husband or brother – legally responsible for policing her clothing, with the threat to punish him if she goes outside bare-faced. In this report, we hear from women about how they and their families have responded to the order and to what extent the new rules or guidelines have been enforced. Dress codes may seem less consequential than other changes, such as sending women workers home from government offices, hindering women’s travel or stopping older girls from going to school. Still, instructing women to cover their faces in public seems symbolic of the Emirate’s apparent desire to turn Afghan women into entirely invisible, private citizens again, argues Kate Clark, with input from Sayeda Rahimi.

The Taleban’s new order has boiled all this variation down to two versions of what the Taleban consider to be ‘sharia hijab’ – either a burqa or “customary black clothing and shawl,” that is not too thin or too tight, which is presumed to be a reference to the abaya and which should be worn with a niqab.[2] In doing this, the Taleban have taken to the state the right to make decisions about people’s personal lives which, in Afghanistan, would normally be the preserve of the family.

The best option for women, says the order, a translation of which can be read in an appendix to this report, is the burqa, which has been “part of Afghanistan’s dignified culture for centuries.” This is normal dress for most women in the rural south where most Taleban are from and where women typically live in purdah, ie secluded from all men, except close relatives. The order specifies that clothing should not be tight-fitting, and the material should not be so thin as to allow the body to be seen through it, nor so tight as to highlight “parts of the body.” Women are further obliged to cover their faces, except for their eyes, when face-to-face with men who are not their mahram. The very best ‘hijab’, it says, is for women not to leave their homes, unless there is a need.

The order rules that a woman’s male guardian (wali) should ensure she wears sharia hijab and it is he who will be punished for any violation, with an escalation of response: advice and warning at the first violation, then being summoned to the “relevant department,” then three days imprisonment, and finally, on a fourth violation, a court appearance and judicial punishment.

The new rule speaks of hijab as the noble Muslim woman’s “privilege,” something that gives her “dignity” and protects her from “being led astray or committing sin” and from “the evil and corruption of those who are [morally] corrupt” so that women “cannot easily fall prey to the intrigue of immoral circles.” The dress code prevents her appearance causing social disorder or fitna (the same word can also mean rebellion against a lawful ruler). The order casts women as responsible for men’s behaviour and implicitly blames them for any sexual harassment or worse that they suffer if their clothing reveals the face or shape of their bodies.

Up till now the Islamic Emirate had been giving mixed messages as to whether it intended to police women’s clothing and appearance, leaving the door open, apparently, for local variation. Now the Emirate, or at least the high-ranking commission responsible for the new rule, appears to have chosen almost the most rigid option of all – only slightly more ‘lenient’ than the code during the first Emirate, when women and adolescent girls had to wear burqas.[3]

The nature of the order

The order was announced at a ceremony on 7 May 2022 in Kabul by Muhammad Khaled Hanafi, acting Minister for the Invitation and Guidance on Promoting Virtue and Preventing Vice, (Dawat wa Ershad amr bil maruf wa nahi al-munkir), usually shortened to Vice and Virtue or Amr bil Maruf (media report here). This is the Taleban ministry tasked with policing morality. The document is entitled, “Explanatory and implementation note [proposal, plan or draft] for sharia hijab”. It is signed by an ad hoc commission of senior Taleban, including the acting ministers of education, hajj and awqaf, and justice, and the deputy director of the Office of Administrative Affairs (the director holds a cabinet-equivalent post), which was chaired by Hanafi. Despite the ceremony, the status of the new rule is not completely clear.

The order is stamped with the seal of the Administrative Affairs Office director, suggesting it has the authority of Supreme Leader Hibatullah’s representative in Kabul, but there are no other stamps or notes detailing the registration of this order, nor a date. This might indicate the order was issued without the involvement of the bureaucratic machinery, and possibly was not registered or, because there is no consistency yet in this field, this may not be significant at all.[4]

In the absence of a constitution, or clarity on the different types of official documents used by the Taleban, the status of the order is not completely clear. Drawing on traditions of Afghan statehood, it can be said that this is not a decree (farman), which is signed off by the head of state and carries the force of law. The text does contain a hukm, which is an order or command – weaker than a decree, but still with the weight of executive authority. A hukm would typically be used, for example, to grant a petition or appoint an official. However, in this case, the actual order in the document is an explicit, but very general, religious command: “Adherence to sharia hijab is obligatory for [all] noble Muslim females from adolescence onwards.” The rest of the document contains a definition of hijab, describes the different types of hijab, details whom the order applies to, and how it should be implemented. Some Taleban, including the influential Minister of Interior Sirajuddin Haqqani, have insisted the order is advisory only. However, the text leaves considerable room for interpretation on the ground, as AAN’s legal expert, Ehsan Qaane, points out:

Analysing this hukm, based on its provisions, only the part which deals with the punishments of the guardian of a woman deemed to be without hijab could be said to rise to the level of criminal procedures. The larger part of its provisions read as recommendations and guidance and do not fit the legal standards normally found in a legislative order (hukm). However, when it comes to the execution of orders like this one, it is a matter of how individual Taleban officials interpret the order and whether and indeed how they decide to execute it.

The commission’s proposal follows other moves by the state to restrict the actions of women and girls – banning most women from government offices, making it a legal requirement for women to travel only with a mahram (close male relative: either a husband, or a male relative whom she cannot marry, such as a brother, father, son or uncle), gender-segregating universities and keeping schools for older girls closed.

It has been noticeable that the Taleban have introduced rules and restrictions gradually since they took power and that they have recently become much harsher than in August and September 2021. This may be due to the Taleban in general consolidating their power and feeling increasingly able to impose their views on the population. There are also indications that the less ultra-conservative elements (often called ‘moderates’ or ‘pragmatists’) have been sidelined in policy decisions.[5] In the case of public morality, however, even the ‘moderates’ within the Taleban, who generally favour less restrictive rules, believe in the state’s duty to impose norms of behaviour on the population, and many still focus their attention on what women do. Indeed, they may feel that not making the burqa, as it was in the 1990s, the only choice is a concession. (For an exploration of why the Taleban emphasise behaviour, outward appearance and ritual, our 2017 special report Ideology in the Afghan Taleban by Anand Gopal and Alex Strick van Linschoten is enlightening.)

The major question, now, is what the status of this order will turn out to be in practice, how it is received by the population and how assiduously the Taleban seek to enforce it.

To get an idea of what has been happening across the country since the release of the proposal, AAN has spoken to 14 women in 10 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. Interviews were conducted in the week of 9 May (ie a few days after the order was circulated on the media). We asked interviewees what they and other local women were wearing before the order, how the order has been greeted locally, and whether the Taleban were moving to enforce it. We made a second round of calls just before publication to check if there had been any developments. The women are from the provincial capitals of Balkh, Badghis, Baghlan, Bamyan, Farah, Herat, Jawzjan, Kabul, Kandahar and Panjshir and are largely young and unmarried. Older women and those living in rural areas may have different perspectives, but even this small sample gives a flavour of the variety of pre-existing norms on what women wear in Afghanistan, the local mores and the concerns – or, in some cases, the relative lack of concern – of women and their families with regard to the Taleban’s enforcement of their dress code.

The impact of the order on how women dress in ten provinces

In Herat, a high-school graduate who works as a graphic designer said that in her city, most women tended to wear chador namaz (Iranian-style chador), a manteau (which could be short or long) or an abaya, and that burqas were worn only rarely. “The order,” she said, “has made no difference to what women are wearing in Herat. Some women are wearing face masks [of the type used to protect people from coronavirus infection], maybe out of fear of the Taleban. I myself wear a long manteau and don’t cover my face.” At the checkposts, she said, Taleban were not checking women’s clothing and Amr bil Maruf, the Taleban charged with ensuring public morality, were not active around the city. She doubted the Taleban could change what she and other women wore.

Herati people are very sensitive in what they will adapt to. The current clothing style is considered hijab in Herat, so no one can force us to change it. If the Taleban forced the people [to change their clothing], they will stand up and organise protests and campaigns – when the schools were closed after reopening, the people and schoolteachers protested. [After the protests, the schools did briefly re-open, before again being closed, the interviewee said.]

Her father, she said, had told her that her hijab was already “perfect” and the Taleban were attempting to impose their ideology on them.

Another interviewee,[6] who is employed at the municipality and who goes into work once a week to sign an attendance form, said they had been ordered to cover their faces at work. She had not done so and had, as yet faced no trouble. She also thought there had been little change in women’s clothing in Herat city, although the number of women and girls now covering their faces with a face mask or a scarf had increased. For herself, she said: “I do not want to quickly obey the rules because if people do that, the Taleban will get used to [their obedience].” As yet, she said, she had not seen Amr bil Maruf inside the city.[7]

A health worker in neighbouring Badghis, described a different situation in her province where most women already wore conservative clothing:

The order has made no difference to what women are wearing in Badghis. We were restricted in the past and we are restricted now. Before the Taleban, almost 70 per cent of older women in Badghis were wearing burqas, while younger women wore white chador namaz, which, in Badghis, women use a part of to cover their faces with. This chador is in our culture and even a 12-year-old girl doesn’t go outside without it. The women in Badghis are still following this style.

She described Amr bil Maruf officials visiting her office the previous week and telling women workers to wear either a burqa or an abaya with niqab. The following day, she said, when they were again at the office, they said her chador namaz did not break their hijab rules, and she could continue wearing it.

The Taleban at checkposts were not bothering women, she said, but were “serious” in their behaviour towards men; her 12-year old brother had returned home weeping the previous day after they had searched him. She thought families might now force their female relatives to start wearing burqas. “So, for instance in my family, even if I don’t want to wear a burqa, my father and brothers will force me to wear it. We Pashtuns are like this,” she said. “My father supports the order.” She said her mother, a school teacher who had herself always worn a burqa outside the house, was also happy with the order. “Afghan women have never lived,” the health worker said. “We have just been alive. Now, we are struggling just to stay alive.”

In another conservative province in the west, Farah, a student at a private university said women there already wore abayas and headscarves, and some wore the face-covering niqab or a face mask. She herself did not cover her face in public, except at the government university, where she said this was now mandatory for female students, as was wearing a black abaya. Her father and brothers, she said, did not agree with the Taleban keeping older girls out of school or compelling women to change their clothing. She said her father, who has seven daughters, was “really sad for us” and told them that everyone has the right to wear their favourite clothes. As a general rule, though, she thought most other people in Farah would have no problem with the order.

Farah is a province that has been restricted for a long time and people have not been free like in Herat and Kabul… Though educated girls might not accept the order and might stand against it, their families will never allow them to [protest].

In Panjshir, a young, now unemployed, woman said she had always worn “proper clothing,” but now her father had said she should get an abaya and her older brother had said she should start wearing a burqa outside the house She said that most of her friends who came to her house were now wearing abayas and “longer clothes,” while she had seen some women locally wearing burqas. It seems that not all of the impetus for change has come from the order itself. She said that due to the large numbers of Taleban fighters in the province, even in the more liberal provincial capital, girls started wearing burqas and abayas “just to be safe from the Taleban because they are so dangerous. Some families have even sent their daughters to Kabul due to fear of the Taleban.” When Afghan women feel unsafe, they typically go out less, and cover up more when they do, to try to attract the least attention from men they do not trust.

In Kandahar, a midwife with ten years’ experience working in private and government hospitals, said the Taleban did not need to enforce the order in her province because women were already following their dress code. “All men agree with the burqa because it has been part of their tradition for a long time,” while “the women who are a little bit freer and who live in Kandahar city are wearing abayas.” She said her female colleagues generally wore black abayas with niqab, as they had done previously, as did most of the women who visited the hospitals, while she herself wore a burqa, and felt “very comfortable with it.” There were times, she said, “when I’ve been speaking as the only woman in front of 70 men including foreigners, wearing a burqa.” Security was better now than under the previous government, she said, and because of that “women have become freer.”

In Baghlan a young woman said that before the Taleban takeover, women had been wearing a mix of clothing, some “clothes like women in Kabul” (presumably manteau, with trousers and a headscarf), while others “wore burqas or abayas.” So far, she said, nothing had changed and Amr bil Maruf had yet to appear in her city of Pul-e Khumri. The Taleban at checkposts had also not sought to impose the order. She said she was already wearing “long clothes” and had previously worn a burqa to go to many places, such as the bazaar, so the order might not make much difference to her life. However, if the Taleban forced her to wear it everywhere, “I’d feel bad because no one likes to be forced to do something.”

In Balkh, the choice facing women is complicated by the fact that secondary schools for girls have remained open since Nawruz, even after the Taleban nationally decided they should be closed. As a result, many women do not want to threaten one hard-won freedom by insisting on another. Our interviewee, who is a teacher, said:

Women are obeying the Taleban order because they don’t want to give them an excuse to close the schools… I think they will be able to enforce this order in Mazar because people don’t want the schools to close.

She said that, given the choice on offer, women preferred to adopt the niqab, rather than the burqa. She herself had worn a burqa for one day following the takeover and found it difficult to breathe: “I couldn’t wear the burqa, but I think I would be able to adapt to it [if I really had to].” Wearing a burqa in hot weather in Mazar, she said, was “heroic.”

As for secondary-aged girls such as her sister, they were now wearing burqas so that they could go to school. The previous day in her street, she had seen Taleban stop two girls from attending class because they were not wearing burqas. She stressed that in her family, the men believed that a woman should not cover her face: “The burqa is not in Islam,” she said, “It is in Afghan culture.” She reported that since the order, the price of burqas in Mazar had gone up.

“I think the order was aimed at the women in Kabul,” said a bank employee in neighbouring Jowzjan. In the past, she said, some women in her province had been wearing “short clothes,” but after the Taleban takeover, that stopped and about 90 per cent of women were covering their faces – wearing a niqab, or a medical mask, or a burqa. Following the order, she said, the ten per cent who had been going outside bare-faced had dwindled further. “Only the elderly and those who have allergies don’t cover their faces,” she said. In her office, she wore a headscarf, in the city an abaya and when she went out into the districts for her work, a burqa. It was more “comfortable” in one aspect because “No one can recognise or disturb me,” but on the other hand, “It is difficult to wear in the hot weather, as I have allergies and become breathless.”

She said Amr bil Maruf were visiting offices and educational establishments offering courses:

They advise women that they must not wear tight, short clothes and must cover their faces, and they tell men and women that they must not see each other, and must study in separate classes… There are so many checkpoints, and, at these checkpoints, they advise the men to have beards and sometimes they even take the men out of the cars for advice. I have not been advised by them yet because I wear a burqa.

She said there had also been an announcement that if women do not wear hijab, they would be fired from their jobs, and their families would be “asked” (to ensure they wore it) and, as a final step, the Taleban would imprison the woman.

Her male customers at the bank had told her the order was making life very difficult for their female relatives. From her own family, she said she had received sympathy and support. Her brother, after walking home from school one day wearing a black medical mask, said he ‘saluted’ the girls who were now wearing black scarves, abayas and niqab to and from school, course or office. Her father was also not happy with the order. She should wear an abaya, her family had said, but it was the up to her whether she covered her face or not:

My family said that if the Taleban came to make me and my sisters’ cover our faces, they would answer them and tell them that our clothing is Islamic, that we don’t wear makeup, and that it is a women’s own choice to cover her face or not.

In Bamyan, a high school graduate said that older women there tended to wear either a chador namaz or a burqa and that girls wore “normal clothes” (presumably manteau, trousers and headscarf). Girls in the provincial capital were “very brave and confident; they wear what they think is suitable for them. The girls neither care what the Taleban think, nor are they afraid of the Taleban.” However, because the order made male relatives responsible for their clothing and the threat was directed towards their fathers and brothers, “many girls,” she said, “are obeying it.” However, in Bamyan, ‘obeying the order’ appears to mean wearing longer clothes and looser trousers than before, with more women and girls wearing an abaya and black headscarf (as our interviewee is now doing), but not covering their faces.

Our interviewee said her own brother had joined Amr bil Maruf, very reluctantly and only because there were no other jobs. He had had to tell her to be careful about her hijab, she said, because of his new role, but his heart was not in the new job. Local men, especially in Bamyan city, were supportive of women, she said. That included her father who had tried to reassure her: “He tells me to be relaxed because the Taleban will only be in power for a short time.”

In recent days, she said, the Taleban have put up several banners in Bamyan city’s bazaar and square, showing a woman with only her eyes visible and with the order: “My sister: Observe your hijab.” She also said Amr bil Maruf had put up notices on schools gates, shops and other places in the provincial capital reinforcing the order, threatening that “anyone who does not follow the Islamic hijab and the guidance of the Islamic Emirate will be dealt with by the law; the responsibility will lie with them.”[8]

It is an irony that during the first Emirate, the banners and notices would themselves have been illegal. The Taleban then condemned all depictions of people, animals and birds as shirk – idolatry – and Amr bil Maruf punished people who violated this order.

In Kabul, known among Afghan women living outside the capital for its relative freedom when it comes to women’s clothing, we spoke to three women in this vast city, to give a flavour of the variety of experiences there.

A woman in charge of monitoring and evaluation for an NGO who lives in Dar ul-Aman and works in Qala-ye Fathullah, said: “A month ago, I was wearing normal clothes to the office, but now the environment is so restricted, I don’t have the confidence to go out without an abaya.” She had had a nasty encounter with a Taleb on a checkpost who shouted at her and two colleagues about their clothing. “Since that day,” she said, “we all are so afraid, we have face masks with us and put them on at checkpoints so the Taleban won’t say something or stop us.” Many more women were now wearing abayas, she said, and some even niqabs and black gloves:

In the past, women were not like this at all and this clothing style is absolutely what they do not want to wear. It is one hundred per cent forced and imposed on women, as it is on me and my family members. No one likes to be covered up this much in hot weather. Women are also human. We need to breathe.

She said most of those enforcing the ban were Taleban at checkposts, whose responsibilities were not clear to her as they have “no specific uniform,” but, she said, they were “the worst”: “[They] are on the roads and have nothing to think about, other than that women must be covered.”

Contrary to the “many people” who had said that, as a Pashtun, she should welcome the order, she said her father had made no comments about what she should wear. She herself had chosen to wear an abaya, she said, to protect her male relatives from the Taleban and she would even wear a niqab if forced to, in order to protect them. She questioned the Islamic validity of the order:

Parents and guardians were Muslims before the Taleban and were careful of their daughters’ clothing in the past and women were observing hijab. My father has no issue with my clothing and has said nothing about it. If the Taleban question him, he’ll say that his daughter’s body is covered. If he has no problem with [what she’s wearing], then who are the Taleban to talk about his daughter’s clothes?

Another woman in Kabul, a teacher-training student who lives in Dasht-e Barchi, the Hazara-majority western neighbourhood, said people in her area were open-minded, which was why the clothing style had been “free” there: girls were wearing jeans, shirts (sometimes short), and long or short manteaux. In the first days of the Taleban takeover, she said women and girls were afraid, so had put on longer clothes or abayas, but slowly, as they observed that the Taleban were not restricting them, they began again to wear the clothes they had worn in the past. Many though, she said, put on an abaya or chador namaz when going outside Barchi, to university or work.

The Taleban’s Amr bil Maruf has not come to Barchi yet [this had changed by the time of the follow-up interview when Amr bil Maruf was present in the neighbourhood], but they stand at Pul-e Sukhta because most women are crossing there when they go to university and office. Many days in the morning I saw Amr bil Maruf questioning girls about why their faces were not covered or their hair not [properly] covered. Amr bil Maruf, in their white coats and white cars,[9]are the ones enforcing this order; the ordinary Talebs and the Taleban police don’t say anything about women’s clothing.

As for her, she said her family was a little religious, so she never had worn very short clothes, but after the Taleban took power, she had bought an abaya despite her father not being happy about it. “He said that in this hot weather, it is hard to wear black clothing.” As for wearing a burqa or niqab, she said that was just “excessive – what I am wearing now is hijab enough.”

A third woman we spoke to in Kabul is one of the small band of women still holding public protests. She said she was already wearing an abaya and covering her face:

I wear the niqab, not to obey the Taleban’s order, but to fight against their rules. In resistance, there are some tactics that we can use to achieve the desired aim. I wear the niqab so that I’m not recognised or arrested by the Taleban, because if they arrest me and my friends, there would be no [women’s rights] movement.

She thought the Taleban’s tactic of making a woman’s guardian responsible for her clothing would ensure greater compliance: “Normally, women accept any kind of violence to keep their family, their father and brothers safe from disrespect and insult.” Because of this, she said, many women would feel forced to obey an order which they had had no part in making, nor any desire to uphold. She said, however, that she had the support of her family in her activism:

Even though my father and brothers are under serious threat, still they will never agree to the Taleban’s rules, not one of them. They also are against this order. It makes them worried about my security, but they do support me in the fight for the next generation of women. If today we don’t stand, tomorrow our children will not have the right to go to school or live freely.

How the women we spoke to feel about the order

The interviews indicate that the impact of the Taleban’s new order, if strictly implemented, will be felt differently across Afghanistan. In places like Kandahar and Badghis, women’s local dress already largely complies with the new code. In other provinces and places, where women have been used to greater freedom and variety, many women have felt forced to amend what they wear, but are loathe to go all the way and cover their faces when they go outside.

Many of our interviewees spoke about feeling frightened, either directly of the Taleban, or of what the Taleban might do to their fathers and brothers if they judged them in violation of the new rules. Some spoke about the psychological impact of the order on their confidence, others of feeling they would not want to leave the house, if forced to wear the burqa or abaya and niqab. It was notable that in many cases their unhappiness was not just about the type of clothing they would have to wear, but the fact that they would be forced to wear it and would have no say of their own and, for those with supportive fathers and brothers, that their family’s autonomy to make decisions had been taken away.

In Mazar, our interviewee said that wearing a burqa or abaya with niqab felt like a necessary sacrifice so that older girls had the best chance of being allowed to keep going to school. In Panjshir, our interviewee described it as a necessary protection against hostile men, in this case Taleban. This matches the experience of those interviewees who were already wearing a burqa when they went to places where they expected to feel exposed, for example, rural districts, or the bazaar. For the women’s rights activist in Kabul, the niqab is a sort of necessary camouflage.

For those women and girls not used to wearing a burqa the thought of it, or the brief experience of trying it out, is nightmarish. The bank worker in Jowzjan said:

At the beginning of the takeover, I wore a burqa for a day. It was so difficult to bear the weight of it and to breathe…. If I have to wear it, I will feel like a free bird being caged. It would be like losing all my freedom to work, my choice, my movement.

The bank worker from Jowzjan who wears a burqa when she goes to the field, also said it was like being a caged bird:

We must wear a burqa because most of the people are staring and the Taleban themselves are also staring. But when I wear a burqa, it gives me a feeling like I am a prisoner, a person who is unable to defend herself, a helpless human being.

The health worker from Badghis said she also already wore a burqa when travelling to the districts, but, “It was my own choice; it would be difficult for me to accept it being forced on me.” She added:

[Being forced to wear it] would be like [the Taleban] were disappearing us completely from the world.

In particular, the enforcement of face coverings, especially the burqa, is viewed by many of our interviewees not only as a physical imposition, but symbolic of the wider restrictions on them as women. As the NGO monitor from Kabul said: “Wearing a burqa or niqab would make me feel like forgetting my all and last hope as a woman.”

The women’s rights protester expressed a similar sentiment:

Human beings are created free, to be able to breathe, to be comfortable. [Choosing one’s] style of clothing is everyone’s basic right. All in all, the burqa is a cage, a chain and an insult. It would be difficult to work, study and move in a burqa, [but that is not all]; it would also be an insult to me. [Wearing] a burqa would be the start of me having no plans, no potential for development or aims because it would imprison not only my body, but also my professional identity and my talents.

Like some of the other interviews, she also defined the issue as not about hijab per se: “Our people have no problem with hijab because hijab has always been valued in Afghanistan. Our protest is against obligatory clothing.” She classed forcing women to wear certain clothing as an act as shocking as removing women workers from government and non-government offices, closing schools for older girls and arresting women protestors; acts that were “anti-woman and violent,” intended to “roll back society.”

Many of our interviewees also disagreed with the Taleban’s contention that the order was about religion. “This clothing style is not in Islam,” said the NGO monitor in Kabul, while the health worker from Badghis argued:

Sin and clothing are personal. The government is not responsible for guiding us to jannah [heaven]. It is responsible for providing livelihoods, work, and other necessities for the people.

If more women do follow the Taleban’s dress code, according to the bank worker from Jowzjan it will be because they have to; it will not be “from the heart.”

Concluding remarks

It is not clear where it all goes from here. This may be an interim period before universal enforcement, as in Iran after the Islamic revolution. The order could be part of negotiations within the movement surrounding school opening and possibly women working. Amr bil Maruf may be trying to test the water to see if it has enough backing within the movement and whether the population seems acquiescent enough for it to clamp down harder on women’s clothing and possibly other rights. The order could also still be quietly treated as advisory.

For now, however, everywhere where the burqa or something similar was not already universally worn, interviewees reported that the order has had an impact on what women wear, as they amend their clothing, primarily in order to avoid potential trouble for themselves or their male relatives. In many places, there have been moves by Amr bil Maruf and/or Taleban at checkpoints to impose the order, usually phrasing it as ‘advice’, although, in Kabul, reported one of our interviewees, by shouting at women to obey it.

Our second round of calls, made in the last few days, showed the Taleban are still mainly disseminating messages about the hijab. In addition to the notices threatening legal action against violators in Bamyan, AAN also heard that in Daikundi’s provincial capital, Nili, Amr bil Maruf had mounted a speaker on top of a car and had driven round the city, advising women to observe Islamic hijab. In Kabul city, as well, a resident in west Kabul reported that the Taleban had put up a notice at the entrance of apartment blocks in her neighbourhood again telling women to observe hijab.[10] There have been no reports of guardians of ‘hijabless’ women being contacted or punished. Nor have there been the sort of public beatings of women deemed to be breaking the Taleban’s dress code, or their guardians, that were seen in the 1990s.

Amr bil Maruf’s usefulness for the Taleban during the first Emirate, as the enforcer of rules on behaviour and appearance, always went beyond ensuring Afghans followed the Taleban’s idea of how good Muslim men and women should behave and dress in public. They were a key element of how the state controlled the population, especially in the cities, an effective means of keeping people frightened. The ministry’s intrusive role may well have helped the state gather intelligence and monitor for potential trouble-makers. It is not clear from the interviews conducted for this report if the role of Amr bil Maruf will turn out to be the same this time round. Interviewees spoke of them visiting mosques, offices and universities, but only a few spoke of them being present at checkposts and none had seen them patrolling the streets, as they did in the 1990s. This may change, of course.

During their first Emirate, the Taleban encountered little public protest against their rulings on behaviour and dress. The country had suffered the horrors of civil war; in Kabul, for example, which the group captured in 1996, tens of thousands of people had been killed and a third of the buildings destroyed. The defeated and demoralised population was relatively easy to control. There was disobedience to Taleban laws – some girls were taught and some women managed to do paid work, people watched videos and listened to music at home – but rule-breaking was done quietly, in secret and in fear, knowing that punishments could be severe. As to clothing, some women pushed at the boundaries: if they could afford it, some women in Kabul wore fashionable shoes, and ‘nice’ clothes under their burqas, which they allowed to billow as they walked to show off what they were wearing underneath.

Twenty years on, the population of cities like Kabul and Herat is far larger. Afghan women and girls and their families, in general, have become used to a much greater degree of freedom and autonomy to make their own decisions. The Taleban may face opposition to this new order, as they try to erase women’s lived experiences of greater freedom, and put their aspirations to be public citizens back in a box. Although, it may seem as if clothing is at the minor end of freedoms, what people wear is both personal and symbolic – and has political implications that are linked to the demonstration of power.[11]

It is significant that the main thrust of the new order is about women covering their faces. The ruling follows two decades in which many women have had public faces and public voices, including as ministers, MPs, judges, professors, street cleaners, TV presenters, police and office workers. Of course, not every girl or woman has had the choice to go to school or get paid work or travel during the Republic – the enjoyment of legal rights was patchy, and corruption, incompetence and poverty meant education and other services did not reach everyone. However, as our special report Between Hope and Fear. Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war, published in July 2021, revealed, many women, even those living in very conservative areas, hoped that peace would bring more freedom when it came to education, travel and playing a greater role in their society. Yet, the end of the conflict has in practice enabled a clamping down on the freedoms that at least some women and girls had enjoyed, and a diminishing of the hopes of others.

Since the takeover, public protest has dwindled as it has become more dangerous. Women’s rights activists have proven the bravest of all, but the Taleban’s response has been harsh – detaining and, reportedly, beating women protesters. Still, the Taleban may find that pushing the state back into people’s lives will be more difficult, and less universally backed within the movement during their second Emirate than it was in the first.

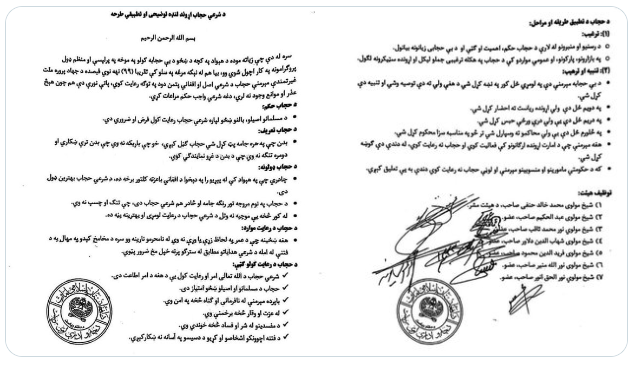

Annex: Translation of the text of the sharia hijab order[12]

A brief descriptive and practical note [proposal, plan or draft] regarding sharia hijab

In the name of God, the most gracious, the most merciful

Although there were constant and systematic countrywide efforts to make women ‘hijabless’ [bi-hijab], fortunately 99 per cent of the proud women of [our] jihad-loving nation still adhered to hijab as sharia and a proud Afghan tradition. The remaining [one per cent] should also follow this obligatory sharia ruling [hukm] as there are no excuses and obstacles [preventing them].

Hijab ruling [hukm]:

Adherence to sharia hijab is obligatory for [all] noble Muslim females from adolescence onwards.

Definition of Hijab:

Any clothing covering the body is considered hijab, providing it is not so thin the body could be visible through it, nor so tight as to highlight body parts.

Hijab types:

- The burqa, which has remained part of the dignified Afghan culture for centuries, is the best form of sharia hijab.

- Customary black clothing and shawl called ‘hijab’ is also sharia hijab, provided it is not thin or tight.

- Not venturing out without cause is the first and best type of adherence to Sharia hijab.

Hijab observance classifications:

According to sharia guidance, females who are not too young or too old are obliged to cover their faces, except for their eyes, when face-to-face with men who are not their mahram [husband or other close male relative whom a woman cannot marry]. This is in order to prevent [social or sexual] disorder [fitna].

Benefits of observing hijab:

- Sharia hijab is the command of God Almighty, and its observance is obedience to his command.

- Hijab is the privilege of noble Muslim women.

- Women wearing hijab are safe from being led astray or committing sins.

- [Hijab makes them] dignified and honourable.

- [Hijab] protects them from the evil and corruption of those who are [morally] corrupt.

- [With hijab] they cannot easily fall prey to the intrigue of immoral circles.

Methods and steps of hijab implementation

Encouragement:

- Explaining the importance and benefits of the hijab ruling and the harms of being without hijab through media and mosques.

- Displaying hijab-promoting texts and related stickers in markets, parks, and public places.

Warning and threats:

- For the first time, after identifying the home of a hijabless woman, her guardian should be issued with advice and warning.

- In the second instance, her guardian should be summoned to the relevant department.

- In the third instance, the guardian should be detained for three days.

- In the fourth instance, the guardian should be handed over to the Courts for appropriate punishment.

- Women not adhering to hijab while working in the Emirate administration, should be dismissed.

- If wives and daughters of government employees and civil servants do not adhere to hijab, their jobs should be suspended.

Assigned Team:

- Sheikh Mawlawi Muhammad Khaled Hanafi, head [Acting Minister Amr bil Maruf]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Abdul Hakim, member [assumed to be the Acting Minister of Justice]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Nur Mohammad Saqeb, member [Acting Minister of Hajj and Awqaf]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Shahabuddin Delawar, member [Acting Minister Mines and Petroleum and former member of Taleban negotiating team in Qatar]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Nurullah Munir, member [Acting Minister of Education]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Fariduddin Mahmud, member [Head of the Academy of Sciences]

- Sheikh Mawlawi Nurulhaq Anwari, member [Deputy Director of Administrative Affairs and former member of Taleban negotiating team in Qatar]

References

| ↑1 | Even in places where some women generally wear less conservative clothing, like Kabul, poorer women may prefer a burqa because it hides clothes they may not feel proud of. Additionally, during the Republic, some women who were working and who had previously worn burqas said they felt the abaya and headscarf, and possibly niqab, or even a full face-veil were ‘smarter’ and more fitting for someone earning an income, while still protecting their modesty. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Whereas in much of the Arab and wider Muslim world, ‘hijab’ refers to a woman covering her head, ie a headscarf, in Afghanistan, hijab tends to be used for clothing that covers the head and body more fully. In parts of Afghanistan – as in the Taleban’s order – a woman may be considered ‘bi-hijab’, ie without hijab, if wearing, for example, a long Iranian-style manteau and headscarf, or shalwar chemise (piran wa tomban or punjabi) and headscarf. |

| ↑3 | There were then extremely few exemptions: the Taleban never forced Kuchi women to cover their faces, even when their caravans travelled through Kabul and other cities, and were never able, or perhaps did not want to police women in remote rural areas where the burqa had never been customary. The author recalls just two other women who were allowed to be bare-faced in public: General Suhaila Sidiq, then-director of the 400-bed military hospital in Kabul, and her sister, Shafiqa, who had been a professor at Kabul Polytechnic when it was open. According to a 2002 Guardian interview quoted in this AAN obituary, a precondition laid down by Suhaila for her to return to work as a surgeon after the Taleban captured Kabul in 1996 was that neither sister would be forced to wear the burqa; her skills were much needed given the ongoing war and the Taleban’s war-wounded. |

| ↑4 | Even during the Republic, it was only in the latter years that a law on legislative documents formally defined different types of order (hukm) and decree (farman). |

| ↑5 | The pronouncement, for example, that secondary schools for girls would remain closed after the start of the new Afghan school year after Nawruz, in late March, after the Ministry of Education had planned and prepared their re-opening, appeared to have come about because of the weight of conservative, rural mullahs within leadership circles – see our report here. |

| ↑6 | Our first interviewee was not available for the follow-up call, so we spoke to a second woman in Herat. |

| ↑7 | Our second interviewee said that at Herat University, the Taleban had attached banners with a famous poem quoting a saying attributed to Fatima Zahra, daughter of the Prophet Muhammad (used also by the Islamic Republic and Iran and Afghanistan’s Shia mujahedin militias):

Oh woman, this is how Fatimah addresses you: The highest value of a woman [lies in her] observing the hijab. |

| ↑8 | For the attention of the dear fellow citizens of Bamyan

This is to notify all Muslim and pious sisters and mothers that from now on, they should observe the Islamic hijab seriously [and] avoid any kind of clothes that are short, tight or leave the face open [uncovered]. From now on, anyone who does not follow the Islamic hijab and the guidance of the Islamic Emirate will be dealt with by the law; the responsibility will lie with them. With respect The Department for the Protection of Virtue and Prevention of Vice The Complaints Registration Office of Bamyan province 8 Jawza 1401 [29 May 2022] |

| ↑9 | “White coats” refers to the new uniform for Amr bil Maruf, ie white piran wa tomban and sometimes white lab coats. |

| ↑10 | In the follow-up calls, only the interviewees in Herat and Bamyan reported further changes in how women dressed since we first spoke to them shortly after the ruling was circulated; in Bamyan, our interviewee reported that more women were now wearing abayas and black headscarves, but no one was covering their face, while our second interviewee in Herat said she had seen increasing numbers of women and girls covering their faces with a scarf or face mask. |

| ↑11 | In Afghanistan’s history, as elsewhere in the Muslim world, forced veiling or unveiling has marked out various changes of regime. Imposing conformity of clothing can also be a vehicle for achieving political ends, for example, as described by Rema Hammami in Gaza in the late 1980s. At that time, the forerunners of the Islamist group, Hamas, the Mujamma, “through a mixture of consent and coercion” and the failure of secular Palestinian men to defend a woman’s right not to cover their heads, managed to transform how Gaza ‘looked,’ thus establishing “a kind of cultural dominance” that belied the group’s actual popularity or strength. Changing what almost all women wore in a matter of months succeeded in bolstering the actual political strength of the Mujamma immeasurably. Rema Hammami, Women, the Hijab and the Intifada, MERIP, 164-165, May/June 1990. |

| ↑12 | With thanks to Daud Junbish for the translation from the original Pashto. |

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 2 Jun 2022

Afghanistan Peace Campaign

Afghanistan Peace Campaign